Favrod Collection/Raccolte Museali Fratelli Alinari, Florence

Unknown artist: View of a Road with Wooden Houses on the Hill of Noge, Near Yokohama, circa 1900; from the book Japanese Dream, a collection of late-nineteenth-century hand-tinted photographs by Felice Beato and others. It has just been published by Hatje Cantz.

Japanese literature is often about nothing happening, because Japanese life is, too. There are few emphases in spoken Japanese—the aim is to remain as level, even as neutral, as possible—and in a classic work like The Tale of Genji, as one recent translator has it, “The more intense the emotion, the more regular the meter.” As in the old-fashioned England in which I grew up—though more unforgivingly so—an individual’s job in public Japan is to keep his private concerns and feelings to himself and to present a surface that gives little away. That the relation of surface to depth is uncertain is part of the point; it offers a degree of protection and lets you be yourself. The fewer words are spoken, the easier it is to believe you’re standing on common ground.

One effect of this careful evenness—a maintenance of the larger harmony, whatever is happening within—is that to live in Japan, to walk through its complex nets of unstatedness, is to receive a rigorous training in attention. You learn to read the small print of life—to notice how the flowers placed in front of the tokonoma scroll have just been changed, in response to a shift in the season, or to register how your visitor is talking about everything except the husband who’s just run out on her. It’s what’s not expressed that sits at the heart of a haiku; a classic sumi-e brush-and-ink drawing leaves as much open space as possible at its center so that it becomes not a statement but a suggestion, an invitation to a collaboration.

The viewer or reader has to supply much of the meaning to a scene, and so the colorless surfaces again advance a sense of collusion, which in turn leads to a kind of intimacy (“Kyoto is lovely, isn’t it?” is one of the central emotional sentences in the novel The Gate, written in 1910 by the much-admired novelist Natsume Soseki.1 The response of the other leading character, quintessence of Japan, is to think to himself, “Yes, Kyoto was lovely indeed”). For the visitor who has just arrived in the country of conflict avoidance, the innocent browser who’s just picked up a twentieth-century Japanese novel, it means that the first impression may be of scrupulous blandness, an evasion of all stress, self-erasure. For those who’ve begun to inhabit this world, it means living in a realm of detonations, under the surface and between the lines.

Soseki’s main characters are masters of doing nothing at all. They abhor action and decision as scrupulously as Bartleby the scrivener does with his “I prefer not to”; the drama in their stories nearly always takes place within, in secrets revealed to or by them. This creed of doing nothing is a curious one in a country that seems constantly on the move, but in Soseki’s world doing nothing should never be mistaken for feeling too little or lacking a vision or doctrine.

Turn to his often overlooked novel The Gate, for example (a new translation of which came out in December from New York Review Books2), and you see that its central events include a character who falls terrifyingly ill, only for no terrible drama to follow; a long-feared reunion that never takes place; and a search for spiritual revelation that reveals very little. Again and again the author stresses that his protagonists—the couple Sosuke and Oyone, sharing a small house in Tokyo at the beginning of the twentieth century, when the book was written—inhabit “mundane circumstances,” as befits those who are “lackluster and thoroughly ordinary to begin with.”

But look closer and you see how much is happening between the spaces and in the silences. To take an example almost at random, Chapter 5 begins with Sosuke’s aunt, much discussed but always somewhere else, finally visiting his house, and exchanging pleasantries—you could call them platitudes—with her nephew’s wife. Nothing could be more ordinary or without effect. Yet notice that the aunt’s first comment is about how unnaturally “chilly” the room is, and recall that the external temperature, and especially the slow change of the seasons, are always telling us something about mood and tone in this book. Part of the point of the novel is that it begins in autumn, takes us through the dark and cold of winter, and ends, in its final passage, with the arrival of spring.

We also learn, in the chapter’s opening paragraphs, that Sosuke’s aunt (on whom his welfare seems to depend) looks strikingly young for her age; we’ve already been told that Sosuke—as his aunt likes to stress—looks unreasonably old for his. We read that Sosuke ascribes his aunt’s healthy appearance to her having only one child, yet even that thought underlines the fact that he and Oyone have none. As the laughter of kids drifts down from the landlord’s house up the embankment—the location itself is no coincidence and sounds coming in from outside are at least as important here as the words that are never exchanged—Sosuke’s wife can’t help feeling “empty and wistful.” The aunt then says that she owes the couple an apology—which conspicuously prevents her from actually offering one—and refers pointedly to her son’s graduation from university (since Sosuke, we’ve already been told, owes much of his present predicament to having dropped out).

Advertisement

The whole scene might be taking place around me, every hour, in the modern Western suburb of the eighth-century Japanese capital, Nara, where I’ve been living for twenty years. “Oh, you look so well,” a woman says to another outside the post office, emphasizing, with a craft worthy of a Jane Austen character, that she didn’t before, and might not be expected to now. “It’s only because I have so little to worry about,” the other will respond, to put the first one in her place. “It’s hot, isn’t it?” the first will now say, perhaps to suggest that nothing lasts forever. “Isn’t it?” says the second, and no observer could find any evidence for the combat that’s just been concluded.

As Sosuke’s aunt, in The Gate, goes on about how her son is getting into “com-buschon engines,” and on his way to profits so “huge” they could ruin his health, she’s drawing attention to the money she’s not giving to Sosuke, the success of her son by comparison—and, in Meiji Japan, the fact that her son is eagerly taking on the Western and the modern world, and not stuck in his Japanese ways, or the past, as Sosuke seems to be. Sosuke himself, meanwhile, is characteristically absent, at the dentist’s office, taking care of a problem that his wife ascribes to age.

A magazine he picks up in the dentist’s waiting room is called Success, and extols the furious movement that is exactly what seems closed to him. He reads therein a Chinese poem, about drifting clouds and the moon, and finds himself at once moved by the realm of changeless acceptance and natural calm it describes, yet excluded from its quietude as well. When the dentist appears—he, too, has a “youthful-looking face” despite his thinning hair—he tells Sosuke that his teeth are rotting and his condition “incurable.” He then removes a “thin strand” of nerve. Back home, Sosuke picks up a copy of Confucius’s Analects before going to sleep, but they have “not a thing” to offer him.

Nothing much has happened, you might say, if you consider the seven pages that have just passed. But we’ve learned more about Sosuke, his anxiety, his relations with his aunt, his premature sense of decay, and his (and his culture’s) inability to commit themselves either to Success or to the culture of old China than any amount of drama could provide. Everything is there, if only you can savor the ellipses.

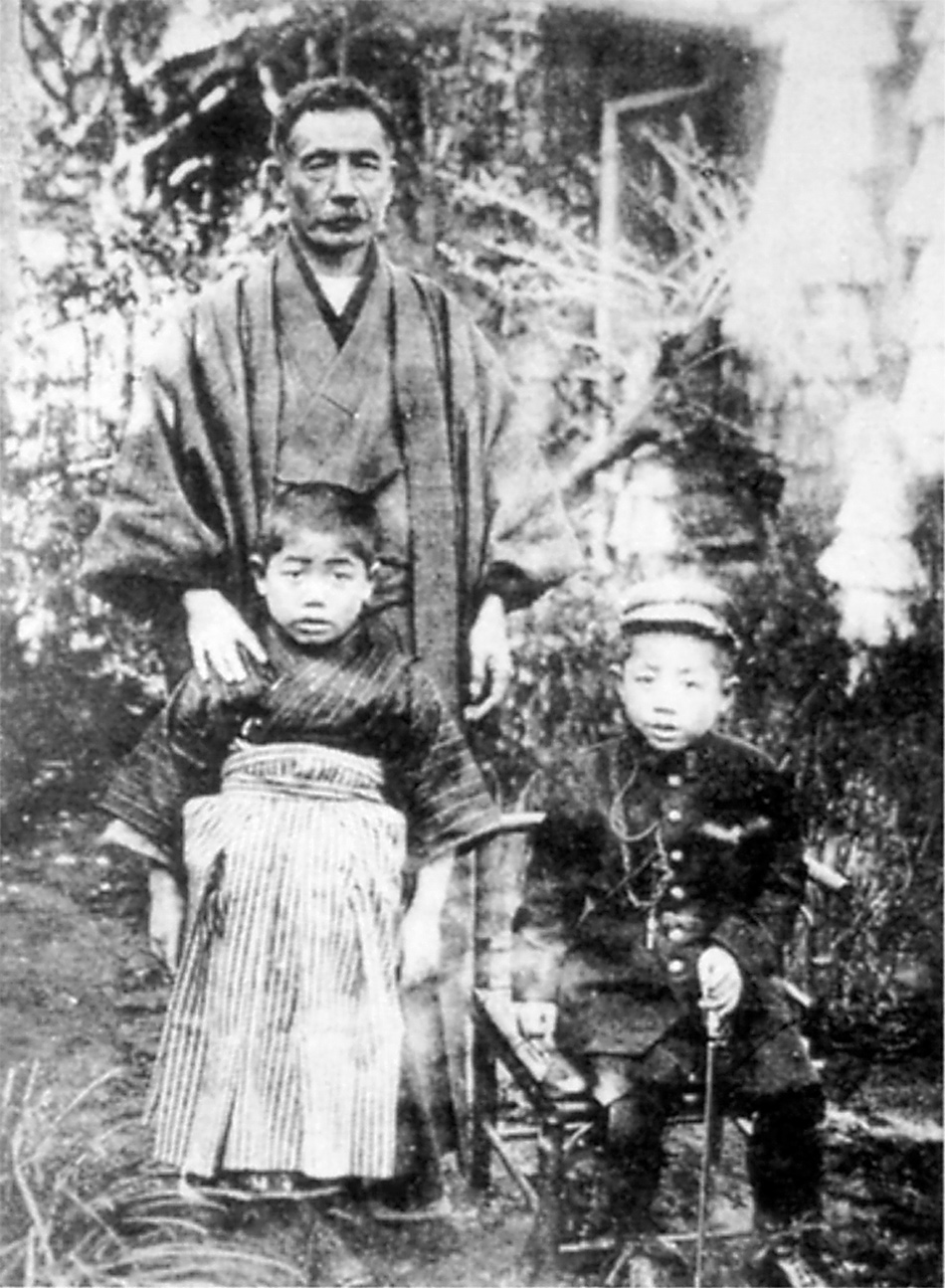

Literary critics will tell you that Soseki was almost unique among the writers of his day because he was sent on a Japanese Ministry of Education program to live in England at the age of thirty-three, and brought back from his two years there an even more pronounced taste for the nineteenth-century English fiction he’d already mastered at home. They will remind you that he was born in 1867, a year before the Meiji Restoration changed the face of Japan, and released it from more than two hundred years of self-imposed isolation (since 1635 or so, it had been illegal for any Japanese to leave the nation). They will observe that he became the defining novelist of the Meiji Period in part because he embraced in his life the central question of the day, which was how his country could combine “Japanese spirit, Western technology,” trying to elide through slogan-making what could be whole centuries of differences. The great novelists who would follow later in the century—Yasunari Kawabata, Junichiro Tanizaki, and Yukio Mishima—would all, in their different ways, be writing about how Japan had already lost its integrity and its soul to the West.

Soseki’s time in London was famously miserable—he felt himself “a poor dog that had strayed among a pack of wolves” and almost lost his mind among what seemed to him cold people and strange customs—but after his return to Japan, he took over Lafcadio Hearn’s position teaching English literature at Tokyo Imperial University, the country’s Harvard (and Soseki’s alma mater, where he had been only the second Japanese to graduate in English literature). He left the university in 1907, after a series of nervous breakdowns, and then published nearly all his fourteen novels in nine years before dying in Tokyo, where he had been born, at forty-nine, in 1916, four years after the Meiji Period ended. He dabbled in stream-of-consciousness narratives, Arthurian tales, satires, detective stories, and travel pieces, yet even the titles of his books (such as Sorekara, or And Then) often stress the fact of nothing happening.

Advertisement

A little as his life story suggests, the man himself seems at once profoundly Japanese and something of a rebel; over and over in his books we meet a quiet maverick who, because of some moment of passion that he feels he must spend his life atoning for, has all but opted out of society, and abandoned every trace of initiative. His withdrawal from action marks him as a failure in Japanese terms, but it may also suggest his deference to the workings of fate, or “karmic retribution,” as the protagonist puts it in The Gate—and even a pride at not participating in a world of ambition and exploitation. Soseki’s wounds are never far from the surface of his books—the hovering around a gate through which his characters will never pass, figures in dire financial straits with holes in their shoes and leaking ceilings, an obscure sense that there is “guilt in loving.” His characters defect from Japanese society without quite arriving anywhere else.

The Gate, for example, puts us into its prevailing mood—and theme—from its first paragraph. A man is lying on his veranda in the autumn light of a regular Sunday, and very quickly we are in the relaxed, undramatic world of day-to-day life, while also feeling an edge to things, allied perhaps to that character’s “case of nerves.” The novel seems to delight in casual descriptions of Tokyo in 1909—we hear the “clatter of wooden clogs” in the street, see the ads in a streetcar (“WE MAKE MOVING EASY”), read of posters advertising a new movie based on a Tolstoy story. But of course none of these details is casual, and all intensify the sense of restlessness and regret that seems to haunt the man on his veranda. The more Sosuke keeps insisting on how his is a life of no consequence, the more we may wonder what all this deliberate stasis is concealing.

Thus the novel quickly establishes itself as a story of absences and withholdings, about all the things that aren’t spoken about, but that keep on ticking away in the background like the couple’s pendulum clock. The prematurely old and settled young partners, going through their unchanging motions, look at Sosuke’s brother Koroku, ten years younger, and feel the impatience and drive they’ve lost. They carefully step around everything they’ve been thinking about—the fact that Sosuke longs to find what you could call the courage of his non-conviction and that their lives seem already to be behind them. Soseki builds a powerful kind of tension precisely by giving us so little.

Attentive readers of Haruki Murakami may recognize something of the highly passive, though sympathetic soul in the Tokyo suburbs bewildered by everything that seems to happen to him, or that appears to have abruptly vanished from his life (Murakami has named Soseki, along with Tanizaki, as his personal favorite among the “Japanese national writers”). Others may recall how even Kazuo Ishiguro, though writing in English and having left Japan at the age of six, wrote his first novel, A Pale View of Hills, about people from Nagasaki, a few years after the atomic bomb there, going through a whole book without mentioning it. The central fact of their lives is the one they never speak about.

But perhaps the best way into this world may be to turn to some of the movies of Yasujiro Ozu, one of the essential artists of twentieth-century Japan, whose films are famously quiet, shot at tatami level, with a camera that seldom moves, in long, slow takes, about those pressures that are never explicitly addressed—and draw their titles commonly from the seasons. In Japan, as is often noted, there are separate words for the self you show the world and the one that you reveal behind closed doors; where we regard it as a sin to be reserved at home, the Japanese take it as much more cruel to be too forthcoming in the world. This reticence has little to do with trying to protect oneself, and everything to do with trying to protect others from one’s problems, which shouldn’t be theirs; it’s one reason Japan is so confounding to foreigners, as its people faultlessly sparkle and attend to one another in public, while often seeming passive and unconvinced of their ability to do anything decisive at home.

“Under the sun the couple presented smiles to the world,” Soseki writes, in one of his most beautiful sentences here; “under the moon, they were lost in thought: and so they had quietly passed the years.” At one point Oyone asks her husband, “How are things going for Koroku?”

“Not well at all,” he answers, and with that they both go to sleep.

How to adjust to a world in which the climax of a scene—and sometimes the central event—is going to sleep? We’re going to have to adapt, maybe even invert our sense of priority and our assumptions about what constitutes drama, as most of us foreigners find we must when traveling to Japan. Soseki is an unusually intimate writer—the public world is only his concern by implication—and in Japan (again as in the England that I know) intimacy is shown not by all that you can say to someone else, but by all that you don’t need to say.

Thus the very fact that Sosuke and Oyone express so little to one another in the novel seems almost to intensify, as it underlines, the depth of their shared past; their silences say plenty. While never showing the couple touching or quite baring their hearts, Soseki evinces a sense of closeness—you could call it love—so intense that when one of them falls ill, it becomes hard to read of the other one’s fears. It’s everything that doesn’t get externalized that knits them together in a community of two: one central scene finds Sosuke returning to his home to discover everyone, unsettlingly, asleep; and in perhaps the novel’s most magical moment, Oyone simply walks around their house, watching her husband, and then her maid, in sleep. In his last completed novel, Michikusa (Digressions, though it’s translated as Grass on the Wayside), Soseki gives us a character who’s permanently exhausted and a wife who spends much of her life in bed, hallucinating and having fits.

The fact of nothing happening becomes a source of almost unbearable tension in nearly all of Soseki’s novels. His characters keep waiting to be exposed, or for something to explode (again you can see how Ishiguro might have learned to create suspense from Soseki, just by having a character try to suppress a past that’s always gaining on him). Since Soseki’s people are nearly always hard up, and bound by many conflicting obligations, they’re anyway paralyzed in a practical sense. And since they seem terrified of dependence on others—Soseki himself was raised by a family not his own, and appears never to have outgrown the unsettledness that brought him—their only way of claiming independence is by sitting in a prison they’ve made themselves.

The challenge of a novel like The Gate is to find a way to turn inaction into a kind of higher detachment, suggestive of the sage’s refusal to be swayed by the vicissitudes of the world. One of the first things that may hit a Western reader on entering the world of a Japanese novel—though of course you can find this in Edith Wharton, too—is how every character is effectively a tiny figure in a suffocating world of associations and obligations; where many an American novel might send its protagonist out into the world to make his own destiny, in Sosuke’s Japan he cannot move for all his competing (and unmeetable) responsibilities to his aunt, his younger brother, his wife, and society itself.

Free will is not even an option; simply to entertain the thought is to condemn oneself to an imprisonment more painful still. “For some reason I have become terribly serious since arriving here,” Soseki wrote, in his “Letter from London,” a year after his arrival in England. “Looking and listening to everything around me, I think incessantly of the problem of ‘Japan’s future.’” Its future, then as now, involves trying to make a peace, or form a synthesis, between the ancient Chinese ideal of sitting still and watching the seasons pass, maintaining social harmonies, and the new American way of pushing forward individually, convinced that tomorrow will be better than today.

It’s no wonder that so many of Soseki’s characters are prematurely old (the novel Michikusa is weighed down by this sense, though its figures, like their author, are only around fifty); this is an old man’s—an old culture’s—vision, in which the past has much greater vividness than the future. “Sometimes,” Soseki writes in that book, of his main character, “he could not avoid the thought that his life amounted to little more than simply growing old.” Soseki’s protagonists don’t feel nostalgia—the very title Michikusa could be said to suggest the wish not to go home again—so much as skepticism toward the prospect of getting a new life. New Year’s Day, the central festival of the Japanese calendar, features in many Soseki books, and it is significant only because, for his characters, there’s never a possibility of starting anew or turning a page to begin again.

When Soseki traveled to England, he complained that he couldn’t even “trust myself to a train or cab…their cobweb system was so complicated.” He felt patronized by the cleaning women and landladies who tried to explain their culture to him (already a teacher of English literature) and both pride and insecurity arose as he felt himself superior to people who (physically) were always looking down on him. But if you read the novels, you begin to suspect that this sense of imprisonment was simply something he took with him on the boat to England. Not only is his take on standoffish and ghostly England startlingly similar to a foreigner’s response—even today—to Japan; the England he evokes, of class distinctions and wraiths and people falling on hard times, is almost identical to the Japan he describes in book after book.

In his dismissals of the “lower class” barbarians he meets and the way his bleak London boardinghouses are so far from what English literature led him to expect, he sounds in fact very much like V.S. Naipaul half a century later; yet much like Naipaul, Soseki, for all his unease in Britain, could seem a strikingly European figure when he went back to Tokyo, affecting a frock coat, a mustache, and a love of beef and toast. It is one of the curiosities of Japan, ever since the Meiji Restoration, that its identity has been defined largely by an identity crisis; to this day, both Japanese and those foreigners who contemplate the country keep wondering if it’s leaning too much toward an outdated Confucian past or toward an unsteady Californian future. Is progress cyclical or linear—should people honor their ancestors or their ambitions?—sometimes seems the central question in Japan. Soseki is one of the first writers to make this the heart of his concern, telling individual stories that seem to speak allegorically for something much larger.

Yet what a novel like The Gate only slowly discloses is that all the talk of nothing happening and all the meticulous avoidance of conflict and feeling speak only for too much feeling in the past. Soseki had an uncommonly acute sense of the power of passion—“It is blood that moves the body,” he writes in his central novel, Kokoro—even if he chooses to concentrate on those moments when people live with the embers of what was once a devouring blaze. The problem is not that a character like Sosuke “hated socializing”; it is that, once upon a time, he was “exquisitely socialized,” a flamboyant “bright young man of the modern age,” whose prospects seemed “boundless.” It’s only his acting too strongly that has condemned him to a life of inaction.

It takes a while for a Western reader, perhaps, to see that in Soseki’s novels, as in Japan, external details are not just decoration; they’re the main event. It’s as if foreground and background are reversed, so that it’s the ads in the streetcars, the sound of laughter from a neighbor’s house, the talk about the price of fish that are in fact the emotional heart of the story. A man is robbed and we read on excitedly to see what has happened. But when the victim is revealed, he “did not appear in the least ruffled” and sits at home with a palpable sense of well-being, talking about his dog who’s off at the vet’s.

In a certain light, this is the character who’s found the peace that all Soseki’s characters long for, just by sitting apart from events and not letting them affect his joie de vivre. In The Gate, indeed, his very confidence is rewarded by his receiving back the watch that was stolen from him. By the end of the novel, though unmoved by Confucius and all talk of Buddhism, Soseki’s protagonist suddenly takes off on a ten-day retreat to a Zen temple in the mountains, and there discovers a world in which the fact of nothing happening can be a kind of blessing.

Nothing can be known or controlled, Zen training teaches; the only thing you can do is scrub floors and do your rounds and perhaps clear your head in the process. Enlightenment comes nowhere but in the everyday; self-realization arrives only when you throw self—and any idea of realization—out the window. Accept life and what it gives you and then you become a part of it.

It may seem strange that Japan’s favorite novelist was an anxious, passive, haunted character writing about nervous disorders and falling asleep and paralysis (even the dog at the vet’s is suffering from a “nervous ailment”). But it speaks for an inner world—and again this is evident in Murakami—that sits in a different dimension from the smooth-running, flawlessly attentive, and all but anonymous machine that keeps the public order moving so efficiently forward in Japan. Perhaps the novel has always been one way in which a person can get his own back at the world; perhaps this is even one of the more useful souvenirs Soseki brought back from his life-changing stay in England. One of his most celebrated essays, the text of a lecture delivered two years before his death, was called “My Individualism” and in it he spoke out against a “nationalism” that, only a generation later, would indeed become poisonous.

Nothing is happening on the surface of his characters’ lives even as so much in the public domain seems a whirlwind of movement and perpetual self-reinvention. But each of these may be as deceiving as the other, as evidenced by the fact that, after a century of turmoil and convulsive change, Japan seems not so different, in its questions, from where it was in Soseki’s time. In Soseki, as in Japan, it’s the fact of nothing happening that makes for a tingle of expectation, a sense of imminent passion, and, in the end, the kind of privacy that stings.

-

1

“Natsume” is in fact the writer’s family name, and “Soseki” a pen name he took on, derived from the Chinese term for “stubborn.” In Japan he is always and only known as “Natsume Soseki,” in the classic Japanese way of using the family name first. More modern writers—such as Yasunari Kawabata, Yukio Mishima, Junichiro Tanizaki, and Haruki Murakami—are more easily, as here, referred to in the Western order, with their family name last. ↩

-

2

The translation is by William F. Sibley; this essay appears in slightly different form as an introduction. ↩