Belvedere, Vienna

Painting by Gustav Klimt, 1912; from Gustav Klimt: The Complete Paintings, which collects his portraits, landscapes, drawings, and letters, along with newly commissioned photographs of his mosaics for the Palais Stoclet in Brussels. It is edited by Tobias G. Natter and has just been published by Taschen.

In a brief acknowledgment at the end of The Life of Objects, Susanna Moore explains that the impulse to write her novel arose during her stay at the American Academy in Berlin in 2006. In a radio interview at the time of publication, she further explained that her protagonist’s Irish origins were not unlike those of her own grandmother. Such details may seem extraneous to the hermetic, almost mystical aura of her beautiful novel, and yet they provide some background to a story that runs the risk of apparent groundlessness. Why should a contemporary American, of all people, write yet another fiction about World War II?

As I, too, discovered during a recent year in that city, it is impossible to sit in a café in the western suburbs of Berlin, surrounded by burgherly, unsmiling septuagenarian and octogenarian patrons with their snowy hair and fine loden coats, and not wonder at their experience of der Zweite Weltkrieg. Unlike their parents or older cousins, these elderly people were children then, innocents in the prolonged riot of destruction and violence that befell Germany in the latter years of the conflict. In North America as in Britain, we have been raised with many vastly disparate but overwhelming narratives of suffering from World War II, stories that unfold anywhere from Denmark to China to Libya and all points in between. But until fairly recently the challenges faced by many German citizens have not been a part of what most of us have learned.

Not until I spent time in Berlin did I become clearly aware, for example, of the staggering statistics that in Hamburg, almost 50,000 people were killed in a single night of bombing in July 1943, or that in the war’s final three weeks between April 18 and May 9, 1945, there were 70,000 casualties in Berlin alone, of which approximately one third were civilians.

During the last few years, some books have given a new sense of the German war experience, among them W.G. Sebald’s lectures On the Natural History of Destruction, the belated English translation of Hans Fellada’s novel Every Man Dies Alone (2009; in German, 1947), and the anonymous diary of end-of-war brutality A Woman in Berlin (in English, 1954; reissued 2006). There have been popular autobiographical accounts by aristocratic ladies in Germany who quietly opposed the Nazi regime, including Christabel Bielenberg’s The Past Is Myself and Marie Vassiltchikov’s Berlin Diaries.

Inevitably, many stories remain to be told—and among these, many would be distinctly unpalatable—but we must welcome accounts that elucidate, for a North American reader, the complexity of human existence in compromised circumstances. Europeans, themselves survivors of such compromise, may understand more. But I was shocked when a fellow scholar in Berlin, an American historian of France of some prominence, essentially denounced my French grandfather as a Nazi sympathizer because—although posted in Salonika at the outbreak of war, with a wife and two small children—he did not quit the French navy at the very first hour to join de Gaulle in Britain.

In The Life of Objects, Susanna Moore has entered this complex territory through the voice of Beatrice Adelaide Palmer, a young, middle-class Irish Protestant, aged seventeen in 1938. In search of adventure and a more glamorous life, she makes her way from Ballycarra, County Mayo, where her parents are shopkeepers, to the care of an aristocratic couple, the Metzenburgs, in Germany on the eve of war. The premise for Beatrice’s escape is somewhat tenuous: she has taught herself to make lace (although, or because, it is a traditionally Catholic pastime), and her handiwork draws the attention of a local notable named Lady Vaughan, who in turn introduces her to a houseguest, Countess Hartenfels.

The glamorous countess, she explains, “suggested that I accompany her to Berlin. I would live in the household of her friends, the Metzenburgs, where I would make lace.” This unlikely proposal is later given credence as a manifestation of the countess’s slipperiness, but Beatrice’s eagerness to accept it is attributable only to youth and naiveté. Her tutor, Mr. Knox, of whom she is very fond (and with whom she will continue to correspond when she is in Germany), alerts her to possible danger, saying that “men who had reason to know were fearful that a war with Germany was coming”; and one imagines that any responsible adult might have suggested that the Metzenburgs, were they in need of a personal lacemaker (itself surely unlikely, in 1938), ought to have gotten in touch with the Palmers directly. But her parents are apparently indifferent, and Beatrice expresses no surprise even in her retrospective account: we are thus to accept her blithe departure as inevitable.

Advertisement

The ultimate purpose behind Countess Hartenfels’s adoption of Beatrice is her own self-protection. This is not overtly stated until the novel’s end, but can be read between the lines:

As we crossed the German border, the Countess, wearing a black silk peignoir (another new word for me, and one with unsettling connotations), suggested that she hold my passport for the rest of the journey, not wishing me to be further troubled by tiresome customs officers.

Unsettlingly distracted by the beautiful lady (rather like the men in the countess’s life), Beatrice fails to notice that her documents have been swiped: it will be a long time before they are returned, and one understands that the countess has made good use of them in the interim.

While on the journey, the countess explains that “she owed everything in the world to Herr Metzenburg. He’d taken her, Inéz Cabral, a young girl of fifteen, straight from Cuba, where he’d found her, and groomed and dressed her.” We may infer, thereby, that Inéz has been Felix Metzenburg’s mistress; and further, from later comments, that she sends Beatrice to him in part as a gift. But the virginal Beatrice remains apparently unaware of this until much later, even as she marvels at the countess’s capacity for mutability and mobility throughout the ensuing years, during which Inéz abandons her count for an Egyptian prince and slips across wartime borders with apparent ease, ending up safely married for the third time to “an English group captain with a large estate near Bath.”

Moore does not portray the countess simply as a villain: she is unfailingly generous with young Beatrice, perhaps as a recompense for leading her into harm’s way, and Beatrice retains above all the memory of the beautiful clothes (“Schiaparelli, Doucet, Lanvin”) that Inéz passes on to her. Tellingly, much later, when Beatrice glimpses Coco Chanel in the company of Baron von Dinklage at the Adlon Hotel in Berlin, she observes that “I was shocked, having not yet understood that it was possible to make beautiful things even if you were corrupt.” This perilous innocent equation—between the beautiful and the good—is surely behind many of Beatrice’s questionable choices, including her decision to remain with Felix and Dorothea Metzenburg once the war has broken out: “The thought of returning to Ireland was so much worse that I determined to make myself indispensable.”

Beatrice’s joining the Metzenburg household—as “Maeve” Palmer, she adopts the nickname given her by her old tutor Mr. Knox—is as apparently mysterious as her departure from Ballycarra. When Inéz sends her to Berlin, no one is waiting for her; her distracted hosts are in the process of packing to retreat to their rural estate south of the city, their city house having been requisitioned by the Nazis because of Felix’s refusal to accept a diplomatic post in Madrid. They have no need of a lacemaker (of course!—although Beatrice registers no surprise at this fact), but are short-staffed—they are attended only by their aged one-eyed manservant Kreck; Dorothea Metzenburg’s personal maid, Fraülein Roeder, “a sour-faced, elderly woman, half squirrel, half bird, in an old-fashioned long black dress”; and the ancient cook, Frau Schmidt—and it seems that Beatrice can be put to immediate use. Indeed, in time she is able, as she wishes, to render herself indispensable. Her role, while not entirely clear, is recognizable: “I didn’t like to think of myself as a servant, but I knew that I fell into that less easily defined company that included governesses and ladies’ maids.”

Once installed at the country estate in Löwendorf, the staff expands to include a young man named Caspar Boerner, nominally the gamekeeper (spared from combat by the three missing fingers on his right hand); and their society is augmented by the scholarly Herr Elias, a Jew from Berlin lying low in the nearby village, who tutors Beatrice in German and, we eventually surmise, becomes romantically involved with both Beatrice and her employer. The barriers of social class perforce fall away in the face of hardship, and this unlikely band comes to form a genuine sort of family.

Beatrice is a curious protagonist, flat in affect, naive in her neutrality, and swayed, above all, by the rarity and beauty of the Metzenburgs’ material lives: “I’d always understood that if I were ever to have the things that I desired I would have to leave Ballycarra—I just hadn’t known how much there was to desire.” Much of the novel is, for the reader, an exercise in parsing clues or traces the significance of which is not immediately clear: it was only on my second reading that I appreciated Beatrice’s decision to be called “Maeve” while in Germany, a detail that becomes relevant when, in a grave fever at the war’s end, she refers repeatedly to “Beatrice” and the name is taken by those around her as proof of her delirious, nonsensical state.

Advertisement

This is just one of the all-but-repressed minutiae from which, with close attention, significant dynamics can be inferred—facts like the Jewish ancestry of both Dorothea Metzenburg and Inéz, or various marital infidelities—and which will be explained in the novel’s final chapter, when Beatrice and Dorothea finally discuss all that has happened.

This masked telling reflects not only Beatrice’s initial unworldliness, but also Moore’s sense of the widespread muting of meaning in aristocratic German society, exacerbated by the terrifying tenor of wartime Germany. (The early-twentieth-century German culture of repressive silence was not limited to aristocrats, of course, as Michael Haneke’s film The White Ribbon so unsettlingly illustrates.) As Beatrice comments, “I understood that I lived in a house of spies…but I also knew that we did not spy [on one another] for gain or even for our beliefs. We spied because it eased our fear.” The close attention to detail without interpretation or attribution of motive places a discreet strain upon the narrative and results in a peculiar and memorable atmosphere, the literary equivalent of a distinct smell. Beatrice, the Metzenburgs and their retinue all remain oddly opaque, characters seen as if in silhouette, moving behind a scrim.

As the novel’s title implies, what Beatrice brings most vividly to life is the Metzenburgs’ vast collections of precious objects. We understand that Felix and Dorothea are constrained by their legacy: their disapproval of the Nazis (a sentiment shared in reality by many aristocratic Germans, although not necessarily for reasons of morality) is counterbalanced by their refusal to abandon the art and artifacts that have defined the family for generations. Inéz says to Beatrice, on one of her last visits to the family,

Do keep an eye on my friend, won’t you? Only a child would refuse to save himself….…And all because he cannot bear to leave his house or his Rembrandts.

From the first, Beatrice understands that “the objects seemed more real to me than the people”:

I’d never seen anything as pretty as the silver plates decorated with bees, snails, and mulberries that had been bought, Kreck said, at the Duchess of Portland’s auction. The dinner service with mythological figures in red and gold had been used by Frederick the Great at Sanssouci. A fluted white beaker and saucer, painted with plump Japanese children, had come from the palace in Dresden….

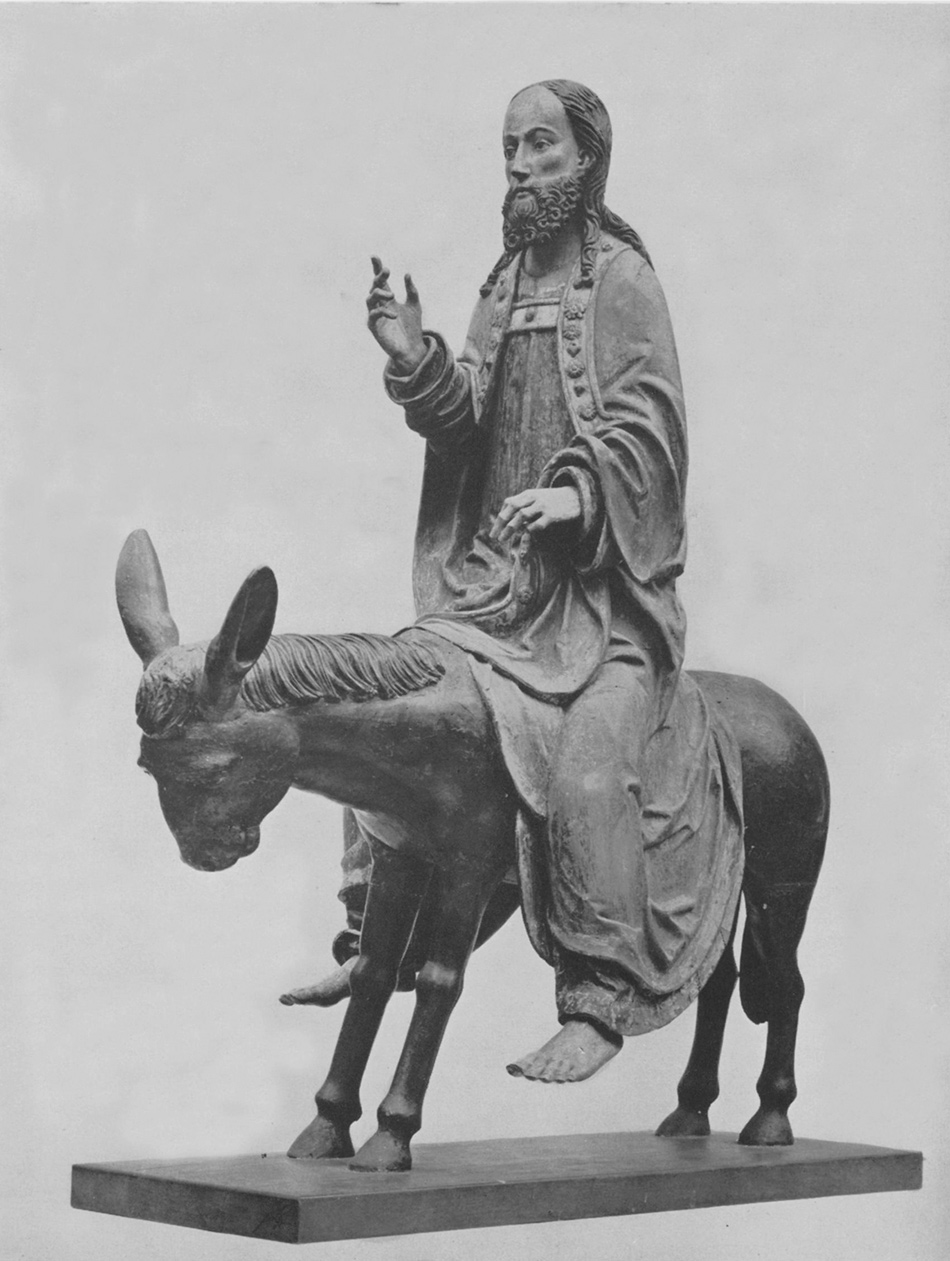

The china is but a fraction of the family wealth that is transferred from Berlin to Löwendorf, along with paintings, silver, linens and lace, valuable books and sculptures, such as “a melancholy barefoot Christ, the size of a child, sitting on the back of an equally downcast donkey. It was called a Palmesel…and it depicted Christ’s entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday.” (It may not be a coincidence that the Palmesel at the Metropolitan Museum’s Cloisters in New York City had once belonged to an Ernst Münzenberger.)

Furthermore, Löwendorf becomes a repository not only for the Metzenburgs’ valuables but also for those of their friends:

Not a week passed when something did not arrive from the Metzenburgs’ friends in Berlin for Felix to hide. Silver teapots and rolled canvases were easily managed, but chairs and tables—even an organ on a wagon drawn by two weary horses—were more difficult.

The entire estate becomes a hoard of buried treasure that will be destroyed by Allied bombs and rampant looting.

At the heart of Felix’s collection is “a painting by Cranach that he kept in his bedroom,” which he initially asks Caspar to bury for him and then chooses to hide instead in the cellar of the Pavilion, a building on the Löwendorf property, “where he could at least look at it now and then.” This painting, which he is later forced to sell and which Beatrice delivers to its Nazi buyer, depicts Venus and an unhappy Cupid swatting at bees, along with a Latin inscription meaning “The pleasures of life are mixed with pain.” Unnamed in the novel, it is one of Cranach’s masterpieces, Cupid Complaining to Venus, which now hangs in London’s National Gallery and was discovered, several years ago, to have made its way into the private collection of Adolf Hitler. (It was then taken from a warehouse in Germany at the end of the war by an American journalist named Patricia Hartwell, who brought it to the United States and eventually sold it.)

Needless to say, the exact fate of this painting is not announced in the novel, and must be inferred. All that Beatrice records is her encounter in the village, at nighttime, with the driver of a black Daimler flying a Nazi flag, and the exchange of the rolled-up painting for a book of Grimm’s Fairy Tales containing a brown envelope and five large hampers of food. Like the Metzenburgs’ hidden treasures, the ever-expanding remarkable stories contained in Beatrice’s narrative lurk beneath its surface. With a little more digging, we may or may not find untold riches.

While never insisted upon—Moore is a mistress of understatement—the ironies of compromise are rife in the novel, for those who care to see them. What appears to Beatrice a life of glamour and worldliness that has been petrified, by hardship, into one of endurance and gritty determination is, in fact, more nuanced.

The Metzenburgs are simultaneously more innocent and more entangled than Beatrice wishes to acknowledge. Aware of the risks, they remain in Germany in order to protect their valuables—and with them, their code of honor and their only known way of life. Unlike the phoenix Inéz, their inner conviction is that they have standing and ethical logic only in Germany: in leaving, they would sacrifice not only their heritage, but their very selves. Their valuables would be destroyed, their way of life usurped. And yet, almost to the last, the Metzenburgs’ treasures can buy them invisible indulgences. They cannot save Herr Elias, it is true; but Cranach’s painting, rolled and delivered like a first-born child into the hands of the Führer, will protect Dorothea’s life—albeit in strips and tatters—until the war’s end.

Then come the Russians: the end of the war destroys the last vestiges of the known. What years of Nazi madness and Allied bombing could not achieve, the Russians accomplish in a matter of weeks: they break the bodies and spirits of these survivors, they shatter irreparably the small Metzenburg family, and reveal the futility of all their efforts. When, sometime later, Dieter, the household’s driver, visits Beatrice and Dorothea in Berlin, he brings “a loaf of sliced white bread, a jar of Nescafé, powdered eggs, and three bars of Palmolive soap from the American PX,” gifts that are, to the women, greater treasure than any gold or silver. This is a new world, in which the chauffeur and his comestibles have more to offer than the grande dame and the remains of her salvaged hoard. Beatrice recognizes that

if the old world had remained the same, I would not have been invited to lunch with Felix at the Adlon, or to swim with Dorothea in the river, or to sit with them after dinner to listen to Jean Sablon sing “Two Sleepy People.” Had the men not been sent to the war and the maids not been forced into slave labor, I would have disappeared into the sewing room with my bobbin and thread. I knew that the war had given me a life.

In the unlikely—but utterly possible—trajectory of Beatrice Palmer, Susanna Moore has shed telling light upon the complexity of ordinary lives in that terrible, tumultuous time. From her modest Irishwoman’s unexpected perspective, Moore grants the contemporary reader access to a long-vanished and long-obscured way of life; and in so doing reminds us of our own unthinking and compromised reality, in which history happens to us and around us, changing us even when we are unaware. Only a few can alter the course of history directly; most of us bumble, often unsure until afterward of what has occurred. Our eyes on the beauty of Inéz’s black silk peignoir, we hand over our passports without thinking; and from such unconsidered moments, lives become changed.

At the novel’s close, Beatrice allows that

over the years I’d learned many things. I was less ignorant, of course, than when I arrived, a greedy girl from the west of Ireland. I’d known nothing of politics….… I knew that I was susceptible to influence….… I was easily impressed and easily gratified.

From that initial position of blithe naiveté, in the company of the Metzenburgs, Beatrice passes through fire into another selfhood, one she would not have renounced in spite of everything: “the war had given me a life.”

This Issue

February 21, 2013

Speak, Memory

13 Questions for John O. Brennan

Double Agents in Love