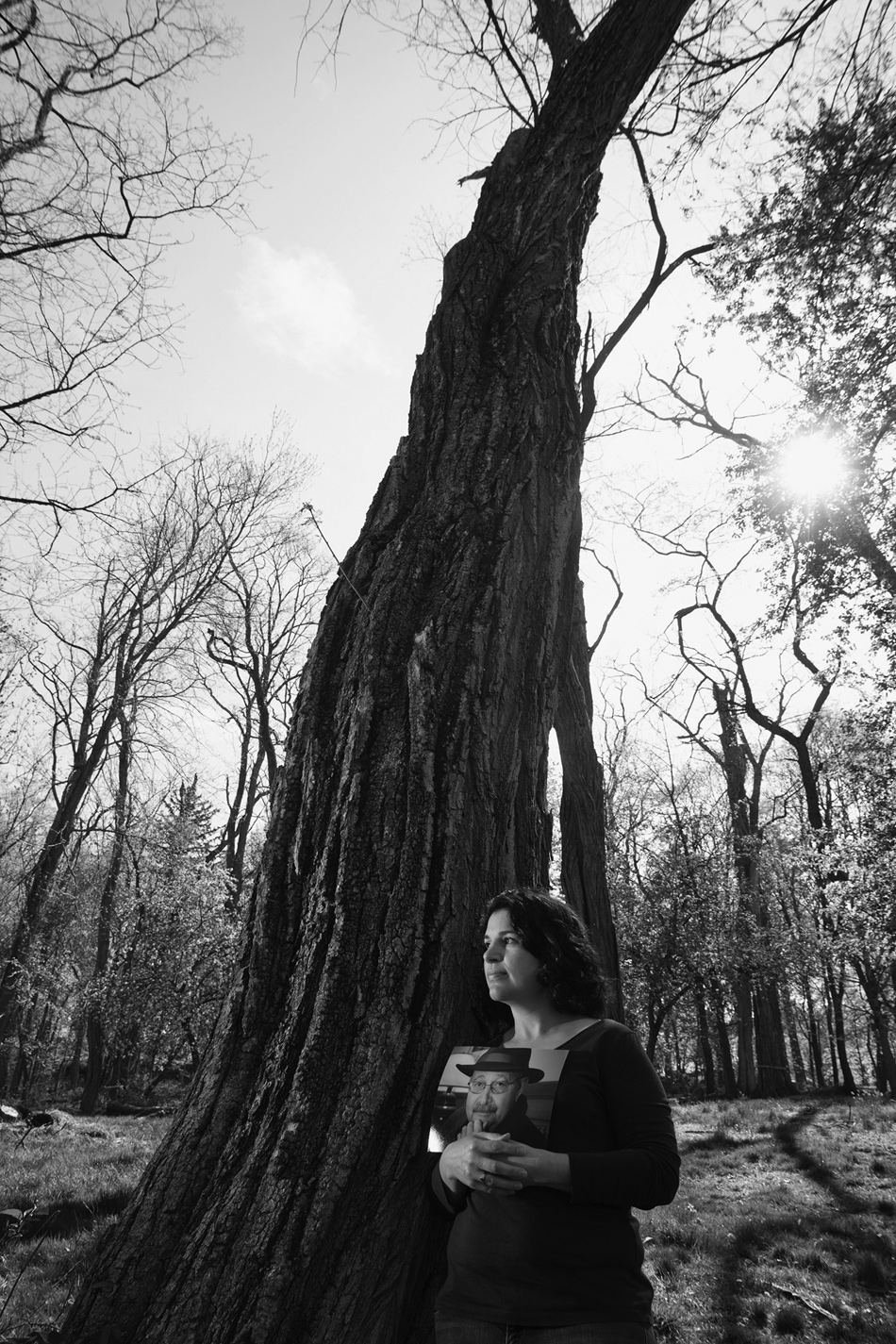

At 2 AM on March 15, 1988, I received a phone call from my mother in Winter Park, Florida, telling me that my father, who was dying of prostate cancer, had taken a pistol from his bedside table and shot himself, preferring to die instantly from the bullet instead of slowly from cancer. He had undergone a series of treatments over several years that held the disease at bay, but now there were no more treatments to be had, and he was rapidly becoming incapacitated. A man of almost obsessive independence, he was unwilling to become helpless and die by inches. Since then, I’ve often thought about the loneliness of his last few moments as he mustered the courage to shoot himself. My mother was sleeping in the next room, and I also think of her shock upon finding his body.

Twenty-three years after my father’s death, Lee Johnson, a man similar to my father in many ways, ended his life quite differently. He was also dying of cancer, but as a resident of Oregon, he used that state’s Death with Dignity law to obtain from his doctor a prescription for an overdose of barbiturates that he could keep on hand and use to hasten his death if he chose. When he decided the time had come, his daughter, Heather Clish, who lives in Massachusetts, joined her mother and sisters at her father’s bedside. Lee Johnson died while holding his wife in his arms, with his family around him.

This form of physician-assisted dying, often called physician-assisted suicide, has been legal in Oregon for fifteen years and in Washington for four years, as a result of voter referendums. As I described in a recent essay in these pages,* the law permits doctors to honor the requests of terminally ill patients whose life expectancy is less than six months for medication to end their lives at a time and under circumstances of their own choosing.

Over the years, the Oregon law has been used sparingly, accounting for at most 0.2 percent of deaths in any year, and it is overwhelmingly supported by the public. More than 80 percent of patients who have died in this manner were suffering from disseminated cancer; most of the others had either late amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (“Lou Gehrig’s disease”) or end-stage emphysema. Nearly all received hospice care (as did my father)—Oregon’s is now among the best in the country—but found it was not enough. As reported by their doctors to the Oregon Public Health Division, their suffering stemmed not so much from pain as from the loss of autonomy. (The experience in the state of Washington, although shorter, is much the same.)

Supporters of the Oregon law were eager to see it enacted in other states, and particularly in an eastern state with less libertarian traditions than the Pacific Northwest. The hope was that if different kinds of states in different parts of the country adopted similar laws, the movement to give dying patients this choice would quickly spread. For a number of reasons, supporters’ attention turned to Massachusetts, which as the most liberal state in the country seemed a natural choice. Yet Massachusetts is also the most Catholic state in the country (45 percent), and that presented a formidable challenge.

The Massachusetts campaign began in the summer of 2011, led by the Death with Dignity National Center, located in Portland, Oregon—the same organization that put the Oregon law on the ballot in 1994 (its implementation was delayed until 1997, when voters approved it a second time, and by a bigger margin). An initial poll of likely Massachusetts voters to gauge its chances showed solid support. The first step was to file a petition, along with the proposed Death with Dignity Act (DWDA), with the state’s attorney general, Martha Coakley. (I was the first of the ten required signatories.)

On September 7, she certified that the proposed law met the requirements for a ballot initiative, and the battle lines were drawn. On the same day, the Massachusetts Catholic Conference, the public policy arm of the church, issued a statement denouncing the effort, and shortly thereafter Cardinal Sean O’Malley, head of the Archdiocese of Boston, in an annual Mass for lawyers and jurists in Boston’s Cathedral of the Holy Cross, referred to “the sheer brutality of helping people to kill themselves.” Nevertheless, despite the official opposition of the Catholic Church, polls showed consistently high public support over the next year—64 percent in favor to 27 percent opposed in mid-September 2012, just seven weeks before the vote.

An offshoot of the Death with Dignity National Center, called Dignity 2012, was formed to oversee the Massachusetts campaign and collect the necessary signatures to put the DWDA on the ballot. The requirement was for 68,911 validated signatures by December 7, 2011. If the state legislature did not take the matter up in its session the following May, and few thought it would, another 11,485 signatures were required by July 3, 2012. Volunteers and paid workers collected signatures outside grocery stores and even wandered around the Occupy Boston encampment. When I asked a couple of them whether they met resistance, they told me that getting the signatures was surprisingly easy. Many people were eager to sign, they said, and mentioned that they had family members who had died difficult deaths and would have welcomed the choice offered by the DWDA.

Advertisement

Because of the favorable polls and the relative ease of collecting the necessary signatures, supporters were optimistic. They pinned a lot on a split between the Catholic public and the church’s hierarchy, as evidenced by the prevalent use of birth control among Catholics, despite the hierarchy’s teachings. Focus groups lent support to that expectation. What seemed to predict attitudes toward the measure was religiosity, not the particular religious denomination. Regular attendance at religious services once a week correlated with opposition, but Catholics were as likely to favor the DWDA as Protestants. In addition, the reputation and finances of the Catholic Church in Massachusetts had been damaged by the sex abuse scandals, and it was assumed that it would not have the resources or will to mount a strong campaign against the DWDA. As it turned out, that assumption was totally wrong.

Supporters also pinned a lot on convincing the Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS) to rescind its long-standing opposition to physician-assisted suicide and declare itself neutral. (It was too much to hope that it would reverse itself entirely and support the DWDA.) At a meeting of its House of Delegates in December 2011, the issue was hotly debated, but in the end, most of the delegates voted to reaffirm the society’s opposition to assisted suicide. They argued, in the words of the then president, that this form of assisted dying is “incompatible with the physician’s role as healer.”

They didn’t seem to recognize that in the case of a terminally ill patient, healing is no longer possible. Although it is impossible to know whether the delegates’ position represented that of most Massachusetts doctors, since there were no statewide polls of doctors, the vote was nevertheless a serious blow to supporters of the DWDA. There was some hope that there would be a split between the MMS hierarchy and the doctors it represents, analogous to that between the Catholic Church hierarchy and its members, but that did not happen. Although many doctors told me they favored the DWDA, only a few were willing to campaign for it openly.

As the campaign heated up, spokespeople for the MMS, including the current president and two ex-presidents, appeared frequently in the media and at professional and public meetings, arguing passionately against the DWDA. In addition to maintaining that doctors should be only “healers,” they argued that no one could be certain that life expectancy was less than six months. That was a red herring, in the sense that while the precise length of life cannot be predicted except as a statistical probability, the diagnosis of terminal illness can be quite certain. There can be no doubt, for example, that the patients in Oregon who used the DWDA to end their lives had fatal diseases. If they had been told they might live longer than six months, it is unlikely that they would have been relieved, since they were asking for an end to suffering that they considered no longer bearable.

The officers of the MMS and other opponents also argued that since all suffering could be relieved with good palliative care, the DWDA was unnecessary—a contention that is obviously not true, since nearly all of the Oregon patients who ended their lives were receiving hospice care. And finally, they argued that the safeguards were inadequate, since even though the law would apply only to adults fully capable of making their own decisions, it did not require consultations with psychiatric and palliative care specialists—an argument that seemed self-serving in implying that dying patients who want to end their lives sooner are a priori in need of the skills of these specialists. (Some, like my father, who had never experienced depression and valued his privacy, would consider a requirement to be seen by a psychiatrist irrational as well as intrusive.)

On the other side were family members of patients who had suffered slow, agonizing deaths, or, like my father and Lee Johnson, had taken their own lives rather than continue to soldier on. Heather Clish, Johnson’s daughter, who is director of conservation and recreation policy for a Boston-based nonprofit organization, became a particularly effective spokesperson, appearing often in the media. She argued that while hastening death would not be a choice most people would make, for those like her father, who greatly value control of the circumstances of their lives, having that choice can mean the difference between a good death and a miserable one. She also pointed out that Johnson, like nearly everyone else who has used the Oregon law, was able to die peacefully at home, where most people say they wish to die, and she contrasted that with the medicalized deaths so many terminally ill patients endure in hospitals.

Advertisement

By the last month of the campaign, it looked like a sure victory for the DWDA. The polls remained highly favorable, and focus groups showed that people strongly supported the essential argument that terminally ill patients should have the right to die in the manner they choose. Even the governor, Deval Patrick, said that he favored the DWDA because of his experience watching his mother and grandmother die protracted deaths; they would have welcomed the control offered by such a law, he said, even if they decided not to end their lives that way. In fact, the appeal of individual choice seemed to overpower every other argument, on both sides.

Yet over that final month, support rapidly melted away. On November 6, even while Massachusetts, true to its standing as the country’s most liberal state, went big for Obama, sent Elizabeth Warren to Washington to reclaim Ted Kennedy’s Senate seat (which had more or less accidentally been lost to Republican Scott Brown two years earlier), and legalized medical marijuana through a ballot referendum that passed 63 to 37 percent, the DWDA lost narrowly, 49 to 51 percent. What happened?

For one thing, opponents outspent supporters by over four to one—$5,451,404.97 to $1,121,921.75, according to the state’s Office of Campaign and Political Finance—and much of that money was spent in the last month of the campaign. The money came mainly from Catholic institutions, both within the state and from dioceses throughout the country, most of it funneled through an organization called the Committee Against Physician-Assisted Suicide. For example, the Boston Catholic Television Center and St. John’s Seminary each contributed $1 million. After the election, Cardinal O’Malley publicly thanked his fellow bishops and Catholic organizations for their help in defeating the DWDA, and was named chairman of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Pro-Life Committee.

In addition, a right-wing organization based in Mississippi, called the American Family Association, contributed $250,000 to the Committee Against Physician-Assisted Suicide, but when its extreme anti-gay views were revealed in the press, the money was returned. Another conservative group, the American Principles Project, headquartered in Washington, D.C., and its chairman of the board donated a total of $673,000 to two opposition groups.

On the other side, support for the initiative came mainly through the efforts of two organizations, Dignity 2012 and Compassion & Choices, a national advocacy group with headquarters in Denver. Both relied mainly on individual donations, which were much less than needed or anticipated.

Opponents mounted a barrage of TV ads in the last month, overseen by Joseph Baerlein of Rasky Baerlein Strategic Communications, who boasts a perfect record in ballot campaigns and called this his toughest fight. These ads were enormously successful in raising doubts among people who initially favored the DWDA. The most effective showed a “pharmacist” grimly pouring hundreds of red capsules into a dish, and lamenting that he was now required to help people to die. People could simply pick up the drugs, he said, and kill themselves, “no doctors, no hospitals, just a hundred of these.” While the ad was misleading (the medication could be dissolved in liquid, so no one would have to swallow a hundred capsules), it raised the specter of terminally ill patients, without any oversight, picking up a lethal medication and dying alone. By taking one of the virtues of the DWDA—the fact that death usually occurs at home and patients can decide whom they want with them—and standing it on its head, this ad played to the common fear people have of being abandoned while they die.

A second reason for the late reversal was the paradoxical effect of the enormously successful campaign to elect Elizabeth Warren. Supporters of the DWDA assumed that they could ride her coattails, in the sense that liberals who voted for her would also be likely to vote for the DWDA. Although that was true of relatively well-educated and affluent white liberals, it turned out not to be true of working-class white liberals or of Latino and black voters. Warren’s ground campaign led to a record turnout of Democratic voters, more even than in the 2008 election, but the urban working-class and minority communities that overwhelmingly supported her were exactly where opposition to the DWDA was greatest. Probably this reflected greater religiosity in working-class communities and perhaps a distrust of doctors among minorities. Whatever the reasons, it came as a surprise to supporters of the DWDA. In addition, Warren’s huge success in raising money from affluent liberals in Massachusetts probably hurt fund-raising efforts for the DWDA, since likely donors may have felt tapped out.

Several newspapers supported the DWDA, notably the Quincy Patriot Ledger, The Berkshire Eagle, and The MetroWest Daily News. But the largest and most important newspaper in Massachusetts, The Boston Globe, opposed it. In an oddly incoherent editorial, it said that as long as some dying patients receive inadequate end-of-life care, they should not be given the choice of hastening their death. The assertion that good end-of-life care is not available to all terminally ill patients is no doubt true, although the editorial offered no evidence. But it makes no sense to hold dying patients hostage to the defects in our health care system by denying them the choice of ending their lives more peacefully—a choice that they might want all the more because of poor palliative care.

Moreover, the experience in Oregon showed that end-of-life care improved after passage of that state’s DWDA, not before. Still, The Boston Globe editorial hurt the chances of passing the DWDA, since many voters don’t familiarize themselves with ballot referendums, but simply take editorials with them into the polling booth and follow their recommendations.

Despite the powerful and well-heeled opposition, the vote was very close, and the issue will not go away. Most people know someone who has died a miserable, protracted death from an incurable illness, and they fear that for themselves. Although it is not possible to put the DWDA on the Massachusetts ballot again for another six years, there will probably be similar initiatives in other states, and also efforts to accomplish the same thing through state legislatures and the courts (the latter was a successful strategy in Montana).

Before the discovery of antibiotics, the lives of cancer patients were often cut off by pneumonia or other infections. But now most cancer patients die in hospitals after a prolonged period of suffering. Good palliative care can alleviate most suffering, but not all. Pain is usually easier to relieve than many other kinds of suffering, such as weakness, loss of bodily functions, shortness of breath, and nausea. Moreover, sometimes the side effects of drugs used to palliate suffering are not acceptable to the patient, as was true in my father’s case. When suffering is extreme and can’t be adequately relieved, doctors often hasten death by administering large doses of opioids, or sedating patients to the point of unconsciousness and allowing them to die of dehydration.

Death that results from these measures is sometimes claimed to be the unintended consequence of efforts to relieve suffering, although it’s hard to imagine that anyone genuinely believes that death from dehydration is unintended. Still, to circumvent laws against euthanasia, these practices occur more or less underground, mainly in hospitals, and often without the express consent of the patient. The DWDA has the advantage of bringing assisted dying into the open, regulating it, and, most important, putting patients in charge.

This Issue

February 21, 2013

Speak, Memory

13 Questions for John O. Brennan

Double Agents in Love

-

*

“May Doctors Help You to Die?,” October 11, 2012. ↩