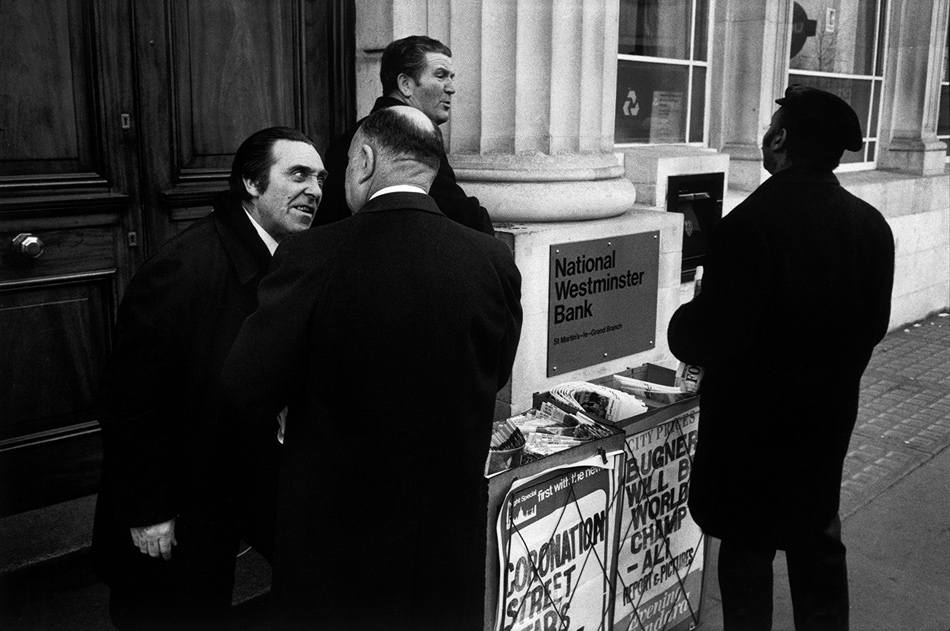

When I moved to London for graduate school back in the early 1980s, the city felt as if it existed for just about every purpose other than for people to make money in it. Everyone was either on the dole or on strike, or about to be—and not just working-class people. No one appeared, or wanted to appear, all that interested in what they did for a living, except for the taxi drivers, who were better than those in the US. In the middle of any work day an extraordinary number of grown-ups looked as if they had just gotten out of bed.

Nothing functioned properly; everything that wasn’t broken was about to fall apart. The food was almost deliberately inedible, an inside joke cooked up by the locals to see what human beings would willingly consume. (I had a friend from Manhattan who said that every time he passed a British sandwich shop “I want to go in and strangle the owner.”) And the most extraordinary anticommercial attitudes could be found, in places that existed for no purpose other than commerce. There was a small grocery store around the corner from my flat, which carried a rare enjoyable British foodstuff, McVities’ biscuits. One morning the biscuits were gone. “Oh, we used to sell those,” said the very sweet woman who ran the place, “but we kept running out, so we don’t bother anymore.”

If you had to pick a city on earth where the American investment banker did not belong, London would have been on any shortlist. In London, circa 1980, the American investment banker had going against him not just widespread commercial lassitude but the locals’ near-constant state of irony. Wherever it traveled, American high finance required an irony-free zone, in which otherwise intelligent people might take seriously inherently absurd events: young people with no experience in finance being paid fortunes to give financial advice, bankers who had never run a business orchestrating takeovers of entire industries, and so on. It was hard to see how the English, with their instinct to not take anything very seriously, could make possible such a space.

Yet they did. And a brand-new social type was born: the highly educated middle-class Brit who was more crassly American than any American. In the early years this new hybrid was so obviously not an indigenous species that he had a certain charm about him, like, say, kudzu in the American South at the end of the nineteenth century, or a pet Burmese python near the Florida Everglades at the end of the twentieth. But then he completely overran the place. Within a decade half the graduates of Oxford and Cambridge were trying to forget whatever they’d been taught about how to live their lives and were remaking themselves in the image of Wall Street. Monty Python was able to survive many things, but Goldman Sachs wasn’t one of them.

The introduction into British life of American ideas of finance, and success, may seem trivial alongside everything else that was happening in Great Britain at the time (Mrs. Thatcher, globalization, the growing weariness with things not working properly, an actually useful collapse of antimarket snobbery), but I don’t think it was. The new American way of financial life arrived in England and created a new set of assumptions and expectations for British elites—who, as it turned out, were dying to get their hands on a new set of assumptions and expectations. The British situation was more dramatic than the American one, because the difference between what you could make on Wall Street versus doing something useful in America, great though it was, was still a lot less than the difference between what you could make for yourself in the City of London versus doing something useful in Great Britain.

In neither place were the windfall gains to the people in finance widely understood for what they were: the upside to big risk-taking, the costs of which would be socialized, if they ever went wrong. For a long time they looked simply like fair compensation for being clever and working hard. But that’s not what they really were; and the net effect of Wall Street’s arrival in London, combined with the other things that were going on, was to get rid of the dole for the poor and replace it with a far more generous, and far more subtle, dole for the rich. The magic of the scheme was that various forms of financial manipulation appeared to the manipulators, and even to the wider public, as a form of achievement. All these kids from Oxford and Cambridge who flooded into Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs weren’t just handed huge piles of money. They were handed new identities: the winners of this new marketplace. They still lived in England but, because of the magnitude of their success, they were now detached from it.

Advertisement

John Lanchester’s novel Capital arrives as a report from the end of this transformation. In Lanchester’s London all sorts of un-English attitudes and behavior that once seemed alien and improbable have now become the natural order of things. The author of several novels, which I haven’t read, and a lovely memoir, which I have, Lanchester has lately turned his attention to finance and economics. His only credential for writing about these difficult subjects, as far as I can tell, is to have grown up with a father who was a banker—though of the old, boring kind who properly disliked his job, and left it as soon as he could afford to.

Yet somehow, in pieces for the London Review of Books and a book about the financial crisis, I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay (2010), Lanchester has turned himself into one of the world’s great explainers of the financial crisis and its aftermath. He has a gift for taking a reader who knows nothing about a complicated topic and leaving him with the feeling that he knows all about it, or at least everything worth knowing. He makes you feel smarter than you are.

The London of Lanchester’s Capital is a very different kind of city from the one I moved to in the early 1980s. Just about everyone in it is preoccupied by money. Some are worried about where to get it; others are defined by how much they already have; but money is in the air they all breathe. (The exception to the rule, a little old lady who has successfully ignored the boom, turns out, upon her death, to have stashed inside the walls of her house £500,000 in small bills.) Money is obviously very much on Lanchester’s mind too. He’s put it into his book’s title, and also into his story’s declared timeline, from the end of 2007 to late 2008, the heat of a financial crisis. He’s put it also into his chosen setting, a single London street, called Pepys Road.

Lanchester opens the story with a long description of all the more or less ordinary things that have occurred on Pepys Road in its hundred-year existence, and then makes his point:

History had sprung an astonishing plot twist on the residents of Pepys Road. For the first time in history, the people who lived in the street were, by global and maybe even by local standards, rich. The thing that made them rich was the very fact that they lived in Pepys Rd…. The houses had become so valuable to people who already lived in them, and so expensive for people who had recently moved into them, that they had become central actors in their own right.

When the book opens, the residents of Pepys Road receive an ominous postcard, a photograph of their newly valuable houses with a single line written on it: We Want What You Have.

Ah, the reader thinks to himself, this will be a sweeping account of the financial crash viewed through the lens of the rich Londoners on this rich person’s road. Oddly, it turns out to be not that kind of book at all because, even more oddly, the author has set in motion a plot that has almost nothing to do with what he really wants to say. The financial crash makes a brief appearance, but only as a nearly pointless afterthought. The reader only ever meets the residents of three of the houses on Pepys Road, and these people have nothing whatever to do with one another—don’t so much as acknowledge one another’s existence. Their houses do not become characters in and of themselves; indeed, they have no bearing at all on the fates of their inhabitants.

The inhabitants, for their part, are either indifferent or oblivious to the fact that they are receiving all these ominous postcards, around which the story is set up to revolve. Despite its great windup, Pepys Road turns out to be nothing more than an excuse for Lanchester to explore the inner lives of a fantastic array of London characters who live and work around it: a Polish builder, a Hungarian nanny, a Zimbabwean meter maid, a police detective, a conceptual artist, a little old lady, a Kenyan football player and his father, an Indian newsagent and his extended family, and above all, a British investment banker and his wife.

And it shouldn’t work. It’s as if the author built the reader a mansion and then insisted that he sleep in a crowded tent out back—in hopes that life inside the tent will prove to be so much fun that the reader will forget about the mansion he was promised. Somehow, it does work. The most obvious reason is that Lanchester is a talented enough writer that you are inclined to follow him wherever he wants to go, without asking a lot of questions along the way. (His books should come with a Do Not Try This At Home label affixed to their jackets.) Take, for example, his description of the private thoughts of his Indian newsagent, as he helps an old lady, who has fallen in his shop, back to her home on Pepys Road:

Advertisement

For Ahmed, who felt that he was always in a rush, that any given day was at its heart an equation with too many tasks and too few minutes, the list of things to do never shrinking while the time in which to do things constantly contracted, there was something very strange about moving so slowly. It was like one of those exercises where they make people walk backwards, or wear blindfolds in their own houses, to make the familiar feel different. He could feel—he couldn’t help himself—a wave of the irritation he so often felt, at so many different things, in the course of an ordinary day. At the same time he managed to slow himself down and check the irritation, by telling himself that there was no point in doing a good deed if all it made you do was feel bad-tempered.

You can find this sort of thing on every other page—a fresh and interesting description of a sensation you might have experienced a hundred times without ever having bothered to attach words to it. The talent for these sorts of small-bore social observations is peculiarly English—it kept Kingsley Amis in business for years, and still makes Alan Bennett’s diaries feel like required reading. Maybe it’s the bad weather. (All those hours trapped indoors, watching one another.) Or maybe it’s the literary side effect of a middle-class culture in which people are expected to be painfully self-conscious, clammy in their own skin, and alert to their own folly and deceptions, lest they be spotted first by others. Whatever the reason, the English really are just better at this sort of thing than anyone on the planet.

Lanchester has the English gift in spades, can deploy it at will, and can seduce the reader into ignoring the fact that he has idled the engine he has created for his own story. He also has a talent for inventing characters—in Capital he’s invented a dozen radically different human beings who have very little to do with one another and yet still never lose interest. One example: Smitty, a semi-cynical twenty-something-year-old conceptual artist who makes a million pounds a year, as Lanchester puts it,

through anonymous artworks in the form of provocations, graffiti, only-just-non-criminal vandalism, and stunts. He was famous for being unknown, a celebrity without identity, and it was agreed that his anonymity was his most interesting artefact—though the stunts made people laugh, too.

As Smitty’s success turns on no one knowing who he is, he sits around his grandmother’s kitchen unable to explain to her why he appears to be suddenly so rich:

As for his nan, saying to her “I am a conceptual artist who specialises in provocative temporary site-specific works” would have been like telling her he was the world heavyweight boxing champion. She would have nodded and said “That’s nice, dear” and felt genuinely proud of him without needing to go into any further details.

But at bottom Lanchester is a moralist, and his story is a morality tale. He has a light touch, but not so light that he can hide what he believes. He believes that life is radically unfair. (He’s attracted to unfairness the way Spider-Man is attracted to crime.) He takes an obvious pleasure in his characters for their own sake, but they all exist mainly to illustrate the radical unfairness he sees all around him: he puts them all to work. If you were to sum up in a single sentence the larger point he wants them to make, it is this: people are never free. Even in this seemingly liberated, highly commercialized environment the luckiest and the richest are trapped. They may inhabit a city that has been transformed into one great free marketplace. But the market, to Lanchester, is not an open and invigorating institution, where Ayn Rand’s heroes triumph, and even ordinary people can be all they can be. It’s just another kind of prison. An agoraphobe’s nightmare.

The cases in point are Roger Yount and his wife, Arabella. The Younts come the closest to being the leading characters of Capital, if only because their lives touch more of the other characters than anyone else’s. They are also something like the summing up of the effects on English existence of three decades of exposure to American-style finance. Roger runs the foreign exchange trading division of a City investment bank, but spends less of his time doing his job than thinking about his money problems. “He wanted to do well and to be seen as doing well,” as Lanchester puts it,

and he did very much want his million-pound bonus. He wanted a million pounds because he had never earned it before and felt it was his due and it was a proof of his masculine worth. But he also wanted it because he needed the money. The figure of £1,000,000 had started as a vague, semi-comic aspiration and had become an actual necessity, something he needed to pay the bills and set his finances on the square.

The chief reason Roger spends so much time worrying about money, in his view, is that his wife requires so much of it to be happy. Arabella’s existence turns on her husband’s ability to generate vast sums of money, and yet she hates him for it, mainly because he is lazy in every aspect of his life not having to do with making money. Here is Lanchester channeling Arabella, on the subject of Roger:

He didn’t cook, except show-off barbecues on the occasional summer weekend at his silly boy-toy gas grill, and he didn’t wash clothes or iron them or sweep the floor or, hardly at all, play with the children. Arabella did not do those things either, not much, but that did not mean she went through life acting as if they did not exist, and it was this obliviousness which drove her so nuts.

Lanchester is a sucker for his own characters, but the only feeling he’s able to generate for these avatars of London money is contempt, which is impressive, in a way. (I half-wondered if he set out to write an entire book about an English investment banker and then decided he wasn’t worth the trouble.) The Younts, unsurprisingly, are also the only characters for whom the reader feels no hope whatever. As bleak as circumstances seem for, say, the Zimbabwean political refugee turned impoverished British meter maid, there is still a chance things will work out for her. She may be all alone in the world and locked up in a detention cell for a crime she did not commit, at serious risk of being sent back to her native country where she will be tortured and murdered—but at least she is not a soulless, loveless, hollow, materialistic monster. On Lanchester’s moral compass British Financial Man represents something like true north, the point against which the other characters can be cleanly measured.

This is, of course, all make-believe. Lanchester controls his fictional world; there is no rule of real life that says if you spend all your time and energy trying to make a million bucks a year you are inherently phony or loathsome, just as there is no rule that says if you devote your time and energy to things other than the relentless pursuit of material gain you are inherently lovable. But in Lanchester’s fictional world, a world that feels plausible and unforced and true, even, I’ll bet, to many people who work in the City of London, the lust for money is a moral disease with an extremely high mortality rate. As I read his story I found myself thinking of recent research done by Dacher Keltner of the University of California, Berkeley, psychology department, showing that rich people are less likely than other people to exhibit compassion, empathy, or concern for anyone’s interest but their own.

I also found myself thinking: the English may finally have decided they have had enough of their experiment with the American financial way of life. If what happened in the Western world financial system had happened at another time in history, there would have been an obvious political response: a revolt against the Roger Younts of the world and, more generally, the grotesque inequities spawned by the putatively free financial marketplace. If the memory of British socialism wasn’t so fresh—if people didn’t still recall just how dreary London felt in 1980—they’d be pulling down the big banks, and redistributing the wealth of the bankers, and it would be hard to find a good argument to stop them from doing it. The absence of the satisfying political response to the financial crisis is due, at least in part, to the absence of an ideological vessel to put it in. No one wants to go forward in the same direction we’ve been heading, but no one wants to turn back either. We’re all trapped, left with, at best, the hope that our elites might experience some kind of moral transformation.

The English, interestingly, have been leading the way on this. Since the financial crash, the Bank of England has consistently been the main source of argument hostile to established financial interests, and made cogent cases for reducing by fiat both the size of banks and the pay of bankers. Most recently the newly elected archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, penned an opinion piece for Bloomberg News, in which he pleaded that “financial services must serve society, and not rule it. They must be integrated into the economy, not semidetached.” And now we have a leading English novelist, and fair-minded soul, showing us the effects of the world we’ve created, or allowed to be created for us. Capital may open as a story about money, but it ends as a story of the limits of money—and with a bit of hope. In its closing line the former British investment banker has lost his job and is finally having a refreshing thought: “All he could find himself thinking was: I can change, I can change, I promise I can change change change.”

This Issue

March 7, 2013

Warrior Petraeus

It’s For Your Own Good!