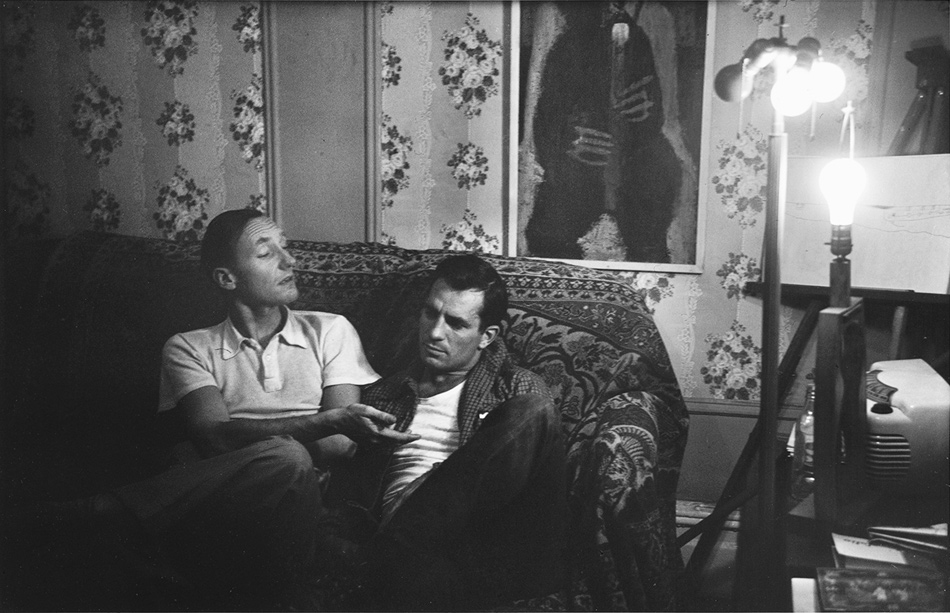

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; © 1953, 2012 Allen Ginsberg LLC. All rights reserved.

William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, photographed by Allen Ginsberg in his East Village living room, 1953; from ‘Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg,’ an exhibition organized by the National Gallery of Art and on view at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery until April 6, 2013. The catalog includes an essay by Sarah Greenough and is published by the National Gallery and DelMonico Books/Prestel.

Jack Kerouac was turned on by the cinema and he fancied himself as Jean Gabin in The Lower Depths. The Renoir film, adapted from the play by Maxim Gorky, was showing one evening in 1940 at the Apollo Theatre in Times Square and the young Columbia footballer sat in the balcony and felt moved by the image of the sainted figure who emerges out of despair. In time to come, Kerouac the writer would appear as a pioneer fixated on the journey west, but it was another direction, the journey down, that really captured him.

If we accept Yeats’s notion that the imagination attracts its affinities, then we can see how the compass was set for Kerouac in 1940. His reading lists no less than his circle of friends were set: they all played into the magic of self-invention behind his life and work. And the reason it all seems so deathlessly teenage is because Jack Kerouac crystalized a great surge of personal yearning at the very moment of its social inception. He couldn’t see what he’d done, and the social movements that grew out of the Beat Generation never suited his politics and overspent on his resources. “It changed my life like it changed everyone else’s,” said Bob Dylan of On the Road.

Kerouac was susceptible to film—a sucker for its promise of riches as well as its flickering poetry—and he imagined an iconic adaptation of On the Road. Not long after the book’s publication, in September 1957, he wrote to Marlon Brando asking him to buy the book and get it made:

Dear Marlon, I’m praying that you’ll buy ON THE ROAD and make a movie of it. Don’t worry about structure, I know how to compress and re-arrange the plot a bit to give perfectly acceptable movie-type structure: making it into one all-inclusive trip instead of the several voyages coast-to-coast in the book.

The letter imagines Brando playing Dean Moriarty and Kerouac himself playing Sal Paradise, offering to introduce Brando to Dean “in real life.” The person he was talking about, Neal Cassady, was, for Kerouac, the perfect postwar all-action hero and man of the moment. He was Byron in blue jeans and a crook out of Jean Genet. For Kerouac he was also the brother who died and the father they never found. “Fact, we can go visit him in Frisco,” wrote Kerouac to Brando, “still a real frantic cat but nowadays settled down with his final wife saying the Lord’s Prayer with his kiddies at night.”

Carolyn Cassady, that “final wife,” saw a lot of the frantic cat and very little of the family man, but that story would wait the better part of fifty years to be told. In the meantime, Brando passed on the film and the Beats themselves became the material. There are a few vital moments when modern creators have come to seem more interesting than what they create: in American literature, we could argue such a condition for Hemingway, for Dorothy Parker, and for Scott and Zelda. They all crossed the line between the making of fiction and the business of constituting a fiction oneself. Movies have been made about each of these writers, yet Kerouac and the Beats, more than any school or group or tradition in American letters, have spawned a miasma of retellings in every genre.

On the Road, as a movie, might have worked brilliantly in 1957 if Brando had accepted the challenge. It might have tapped into the same energy the book did—the same sources that fueled Brando’s The Wild One (1953), the James Dean vehicle Rebel Without a Cause (1955), and The Blackboard Jungle (1955), with Sidney Poitier. These were films that married uncertainty about the old, pre-war order to new feelings about sex; they braided fresh notions of freedom with antisocial frolics, wrapping them inside the brand-new vapors of rock ’n’ roll and the teenager. Just imagine On the Road as directed by, say, Elia Kazan, adapted by William Inge, starring Marlon Brando and a suddenly disheveled Elvis Presley. It might then, if done well, have been part of the now slightly camp-seeming social and sexual uplift that came in time to awaken the 1960s.

But that didn’t happen. Instead, it was the lives of those involved in the Beat Generation that had cultural reality. The movies found that the best subject wasn’t really the books at all but the people who wrote them. That might seem normal nowadays: the personalization of everything is now total. But the Beats, oddly, were probably part of the process by which fictionality became entwined with everyday selfhood. I mean, at least the world got to see Gary Cooper in A Farewell to Arms (1932) before we came to the horrid bio-fiction of Hemingway and Gellhorn (2012). But with the Beats it was always about their lives.

Advertisement

In his famous 1958 essay on the Beats called “The Know-Nothing Bohemians,” Norman Podhoretz assumed no distinction between the frantic cats who wrote these books hopped up on Benzedrine and their spontaneous paw-prints on the page. For him, it was all part of the same primitive discourse. It was a generation of spoiled lives and sick thinking, but quite photogenic, quite zealous for crucifixion on film and television. During the decades when On the Road was failing to hit the screen, and after a more or less silent decade after Kerouac’s death, there has been a spew of movies about the loves, the lore, the fears, and the loathings of the Kerouac tribe, making, it must be said, more than ample use of the word “Beat.” We’ve had Heart Beat (1980) starring Nick Nolte and Sissy Spacek; and what about Beat (2000), with Kiefer Sutherland and Courtney Love? The Beat Hotel came in 2012. The Last Time I Committed Suicide (1997), starring Keanu Reeves, was Neal’s story made from a letter written by Cassady himself. The even more direct Neal Cassady (2007) starred Tate Donovan and Amy Ryan.1

It’s odd now to think of Podhoretz and the Beats as coming from different moral universes. Podhoretz over-played his hand, as if he needed, for reasons of increased self-worth, to believe in the murderous, sexual deviancy of the new Bohemians. In actual fact the Beats now seem pretty innocent: far from being a threatening group of “morally gruesome” primitives, they were a bunch of college kids with a few new things to offer. Kerouac and Podhoretz were both from the universe of book-reading intellectuals faced with the middlebrow trend for refrigerators and mass entertainment.

Sure, they had different views about holding down a job and maintaining a family, opposing views of human vitality, you might say, but they agreed, more fundamentally, that Shakespeare and Thoreau were elements to conjure with if you wanted to live a fuller life. The Beats had plenty of battles on their hands—over censorship, over gay freedom, over drugs, over authority—but they are nonetheless fixed in American culture at the soft end of change. I love him, but Kerouac was, among other things, a right-wing zealot and a sentimental Catholic who supported the war in Vietnam.

He was also, like Cassady, a moronic father whose wonderful notions of fellowship under the American night never extended to paying child support. They were children themselves, in other words, with ruthless souls, allowing Kerouac’s book to tumble and glow with a sense of childlike wonder and capacity. On the Road is a great book because its rebellion is not only hot-wired to a moment of social change but also hastens that change. Its style embodies both the tender effulgence of youth and the solid reality of a passing landscape. But the lives, especially those of Kerouac and Cassady, those poor, bright, sad lives that ended too early and too much in anger, may, in fact, have been impossible. Not only impossible to live but bad to dream. Getting high and feeling great and having friends along the way: What could be better for a summer illusion? What could be nicer?

But it’s not a cultural program, and horribly, without it being their fault, it turns out the Beats may have sold too many Levis and too many plaid shirts for too many vile corporations, while carrying in themselves too few ideas about how a person can resist the complete manufacturing of self. Kerouac never managed that. And neither did his book. Ironically, the “poisonous glorification of the adolescent in American popular culture” that so obsessed Norman Podhoretz in his essay didn’t lead to murder, as he feared and seemingly half-hoped, but to commerce. And in that sense both he and the Beats are losers.

Like the relics of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, the original manucript of On the Road appears to be permanently on tour, and I caught up with it at the British Library. One long roll of text made of telegraph paper stuck together, it is contained in a special glass case, which, at this stop-off, ran down the length of a hall on the ground floor. So much of modern art now has the potency of a relic: you bend to look at it and you don’t think, “Mmm, aren’t the formal questions here brilliantly addressed.” Instead, you think: “Jack touched this.” (The students around me called him Jack. Their main fascination is with the rumor that he wrote it in three weeks.) Is that a wisp of Jack’s cigarette ash smudging the corner? Is that a coffee stain? Is that water damage over there or is it tears? None of the questions we have are to do with the formal story. Not even about the characters. They are about the real people who inspired them.

Advertisement

In the original, Dean Moriarty is just plain old Neal Cassady. Sal Paradise, at this stage, is our friend Jack. And Ginsberg is Ginsberg and everybody else is everybody else. I once asked Robert Giroux, who had been a previous editor of Kerouac, what happened when the novelist arrived at his office with the manuscript of On the Road. (I was recalling his words while looking at the same script under glass.) “He came in with this thing under his arm,” said Giroux, “like a paper towel or something. He held one end of it and threw it across the floor of the office. He was very excited. I think he was high. Anyway, I bent down to look at the thing. And, after a few moments, I looked up and said, ‘Well, Jack. This is going to have to be cut up into pages and edited and so on.’”

“And what happened?” I asked.

“Jack just looked at me and his face darkened,” said Giroux. “And he said, ‘There’ll be no editing. This book was dictated by the Holy Ghost.’ The book then went to Viking and Malcolm Cowley took care of it.”2

Walter Salles’s film of On the Road comes to us more than fifty years after the book’s publication. If the novel was a strange hybrid of the truth and its correction—sold to the world as “spontaneous bop prosody”—then the film takes us even deeper into the mysterious waters of veracity. This is a film of a novel that takes the form of a biography of an icon. It wouldn’t have been made this way in 1957, and, indeed, the story it tells is really the story of our own need, the need of modern audiences, to find reality much more interesting than fiction. The film cannot control its lust for the tang of actuality, forgetting what it takes to dream a prose narrative into being. Yes, Kerouac’s novel was very close to his life, but On the Road is really its prose. One might say the prose is the main character. How quickly it was written and under what conditions, who knows, any more than one can say what was really behind the tone of Charlie Parker when the sound came flowing out of his horn?

The film never finds a way to embody the sound. It just can’t hear it and so we watch a kind of beat soap opera, a play in which the visionary travails of the men can only be set against the domestic woes of the women. The rolling Whitmanesque parade and the singsong bebop amping on chords and words and phrases that makes the book what it is, none of this enters the film at the level of its pictures. We have a voiceover that gutters with a sense of low-watt destiny: the poets and their conversation just seem silly, the locations dreary, the women either sluts or drudges, women either bursting with enthusiasm to give out blow jobs in cars at high speed, or women standing with crying babies balanced on their hip.

Neither Garrett Hedlund (as Dean) nor Sam Riley (as Sal) can convey the type of intelligence the film wishes so much to celebrate: they look like people off a poster and that was always the danger once the book was famous. At no point does the film narrative rise above the car and above the houses, as the book does, to see the stars and the promise they make. That kind of work must be left to the poets, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, aged ninety-four, has just produced a rather bountiful evocation of the Beat spirit, and of Kerouac himself, in his latest volume, Time of Useful Consciousness.3 The film can’t see how much the work of these writers owes to a group sensibility, but Ferlinghetti captures it very openheartedly:

Old friends or lovers once so close

now stick figures in the distance

disappearing

over the horizon

waving back

Goodbye! Goodbye!

Great American prose is notoriously hard to film: we will shortly see whether Baz Luhrman can break a long run of failed attempts to capture the magic of The Great Gatsby.

Readers of On the Road tend to soak up the spontaneity and the lovely sensibility. And it is lovely. Be free. Be open. Be naked in your responses to the world and its peoples. It’s rather like a rolling self-help manual for kids who believe their parents are too invested in private schools and insurance policies. But the new film won’t sell that soft resistance to young people. Instead, it tries to sell, and not very heartily, a story that the modern young are much more used to. A story of relationships going wrong. Dean likes Marylou but Marylou is kinda kooky so he also likes Camille, but Camille likes to be at home with the kids and she also kinda likes Sal. Meanwhile, Sal has a weird thing with his mother but he sleeps with Marylou who is kinda over Dean anyway, but not really. Give or take a few puffs of marijuana, the odd shot of tequila, and a blast of Dizzy Gillespie, this is the kind of deep spiritual involvement you get nowadays on The Real Housewives of Orange County.

At one point in Salles’s film, a rotund, stoned little man called Ed Dunkel (played by Danny Morgan) dumps his wife Galatea (played by Mad Men’s Elisabeth Moss) at the house of heroin addict Old Bull Lee and his mad wife. The guys are having a whale of a time but it’s all pretty out of whack, and, suddenly, Galatea has a speech that would make the writings of Betty Friedan appear like the mouthings of Jayne Mansfield. “You know what these bastards did to me?” she screams at our erstwhile narrator, the not entirely focused Sal Paradise. “Dean leaves his wife and baby penniless cause he wants to visit you. And Ed being a sheep wants to tag along. Only they have no money and Ed asks me for the money and I say, ‘I’m not giving you any unless we are married’ and Dean says, ‘Hey, Ed, stupid ass, marry the broad….’ So he marries me for gas fare and we get in the car and Dean drives like Satan smoking marijuana the whole way and they won’t even stop to let me use the ladies’ room and when I say something about it they dump me in Tucson.” Duly ashamed, the men then repair to a room to discuss Céline while the women scrub the kitchen.

Everything—including Jack Kerouac’s life—seems destined to undermine the magic of On the Road. Maybe that’s just the way it has to be with iconic books. His direct contemporary J.D. Salinger seemed to know as much. With Kerouac, it can seem as if his whole life after 1957 (including his fifty-five-year afterlife) is mired in an attempt to challenge the spirit of what he wrote. Every biography has fresh blunders and renewed shocks, and many of them come from people who slept with him. Some of them even loved him in real life and their books now line the shelves like wallflowers at a 1950s prom.

We might put the male chauvinism down to the times, but what of the Women Beware Women aspect, which seems as strong today as it was in the decade that began with All About Eve? There was no room in the Beat Generation for women writers (the only exception being the poet Diane Di Prima),4 and, even worse, the women who do write seem interested only in writing memoirs glorifying the men, books in which other women come off badly. Carolyn Cassady’s book Off the Road (1990) is a heartening exception to all this: she tried to write honestly and with love, and the picture emerging is of a set of very selfish and often tender men who defined these women’s lives almost to the point of ruin. You would think the women might want to stick together, but that’s not how it works. Here’s Joyce Johnson in her new beat memoir, The Voice Is All:

Although Carolyn was spellbound by Neal’s genius…, she was relieved that he didn’t try to pressure her into having sex with him, since she had soon found out about Luanne. She [Carolyn] was a woman with a great craving for attention—a word that crops up frequently in her memoir Off the Road, and no-one could be more attentive than Neal, once he put his mind to it.

This is snide and competitive, but it gets worse:

On a panel of Beat women fifty years later, Carolyn bluntly described Neal’s approach to making love as “rape.” Nonetheless, she had become hooked on Neal permanently. Once they were married she would accommodate his excesses and transgressions, until the evidence became too much to bear, by remaining in a state of denial as much as she could, and after his death, she would find a kind of queenly, self-justifying pride in the religion she had made of her acceptance.

Johnson’s attitude toward her own sex, I have to say, is questionable, a fact one might have gleaned just by observing the title of the book where she first described her involvement with the Beats: Minor Characters (1987). It is perhaps incumbent upon history’s bit-part players to fight most ferociously over the reputations of the leading men, but Johnson takes it to the limit. After abusing Neal Cassady’s widow—whose chief crime, one presumes, was to be a wife and mother rather than just another of the “Beat women”—Johnson goes on to splat the loyal Kerouac scholar Ann Charters:

Academicians and critics of Charters’s generation, as well as Jack’s, tended to have rigid conceptions of what constituted a novel and what did not and to feel a distinct prejudice against autobiographically-based fiction.

This is an odd thing to say about a woman who had devoted her working life to Kerouac’s writing. A little later on, the rock singer and poet Patti Smith, a “misinformed Kerouac admirer,” gets her butt kicked for suggesting, as the novelist himself very often did, that the work rushed onto the page. And finally, just as you’re beginning to wonder what has made Joyce Johnson so angry with other women who touched or were touched by the Beats, we have her incredible attack on Kerouac’s second wife, Joan Haverty:

Joan had discovered she was going to have a child and was refusing to consider having an abortion…. She had not felt the least grain of sympathy when Jack told her there was no way he could stop writing to support a wife and child. (Her memoir would make it clear that she regarded Jack’s single-minded dedication to his work as a kind of egotistical self-indulgence.)

Wow. Exactly what flame is Joyce Johnson the keeper of? Certainly not the flame of sisterhood. Just to be straight, and I say this as an admirer of On the Road as a literary work: Jack Kerouac changed addresses, jobs, and sometimes even names to avoid paying Joan Haverty child support. The daughter they had, Jan, was appallingly treated by her father (he only ever saw her twice) and they received nothing from his estate. Jan Kerouac became a drug addict who hit the road at fifteen. She later wrote a novel, Baby Driver, had kidney failure, and died at forty-four. Might I suggest that Joyce Johnson could turn one or two of these facts over in her mind before writing about grains of sympathy?

The Voice Is All, reads her title: “The Lonely Victory of Jack Kerouac.” And on these literary scores she has some important points to make: we don’t judge writers, even very holy, freewheeling ones, on how they treat their wives and children, or how they cheat on their girlfriends. We look at the work and we accept what miracles we can, on their own account mainly, but also in lieu of moral perfection. Joyce Johnson went out with Kerouac when she was twenty-two years old and she is now seventy-eight. No matter what else: he was one of her missing men. It is Jack’s struggle that moves her, Jack’s victory, and her decades of empathy might prove now that she was right for him all along. Sexual confusion aside, other women aside, all that Kerouac ever really needed was a loving fan. And he got Johnson. Only she understood him. She waited for years and did well writing books about him and her, and now she teaches writing at his old university.

Life is elsewhere, though. Those kids around Washington Square all learned that from Rimbaud, and Kerouac knew it and so do many of those who found, over time, that they lived both in the novels and out in the world. Whether they were characters, or minor characters, first and last: Who can tell? They were people who survived the icons, the myths, the lawsuits and bad films, and went on with life as best they could.

The other day I got in my car and drove out on the M4 toward Bracknell, one of those leafy suburban spaces outside London. Driving through the countryside I thought of one of Kerouac’s small poems now collected for the first time by the Library of America.5 It is called “Woman” and I thought of it when I saw a washing line flapping in the breeze:

A woman is beautiful

but

you have to swing

and swing and swing

and swing like

a handkerchief in the

wind

I came to a housing park that was uniform and sprawling with similar gardens and fences from Homebase. There were barking dogs and parked cars, and, eventually, Carolyn Cassady, waiting for me at the door of a prefab surrounded by conifer trees. “Go West, young man,” she had said. England was cold that day and the birds were perched on the telegraph poles. We sat down and Mrs. Cassady played me a homemade recording of her late husband and Jack Kerouac reading from Proust at their house in San Jose in 1952. I sat and listened. The wine was on the table and the sandwiches were out and everything was fine. Mrs. Cassady is now ninety years old. “I drove here by satellite navigation,” I said. “Your life might’ve been quite different with that.”

The voice of Jack Kerouac filled the room. He was singing “A Foggy Day in London Town,” but he didn’t know the words, and he scatted over it and laughed. It was odd to hear him humming down the decades with the English afternoon outside.

“Well, we had maps,” said Mrs. Cassady. “But they didn’t use them.” She lifted her glass. She smiled. “The boys didn’t know where they were going. They didn’t. Not really. They just knew that they wanted to go.”

This Issue

March 21, 2013

When the Jihad Came to Mali

Homunculism

The Noble Dreams of Piero

-

1

There are subgenres. William Burroughs, for example. There are also countless documentaries. And there are other categories altogether, such as pop songs written about the Beats. ↩

-

2

The extent to which the book was edited, and revised by Kerouac, was made clear by Cowley himself. His words are quoted in a new edition of Jack’s Book: An Oral Biography of Jack Kerouac by Barry Gifford and Lawrence Lee (Penguin, 2012). “Jack did something that he would never admit to later,” says Cowley. “He did a good deal of revision, and it was very good revision.” ↩

-

3

New Directions, 2012. ↩

-

4

Bill Morgan forcefully takes up the point in his new book The Typewriter Is Holy: The Complete Uncensored History of the Beat Generation (Free Press, 2010): “Although many Beat writers treated women badly, Burroughs was arguably the worst…. He was quoted as saying that he regarded women as an alien virus that needed to be segragated from men. Ginsberg never hated women in the way that Burroughs did, but he often overlooked or ignored them without realizing it.” ↩

-

5

Jack Kerouac, Collected Poems, edited by Marilène Phipps-Kettlewell (Library of America, 2012). ↩