An ordinary winter evening in the Legation Quarter of Peking, where foreign embassies and consulates were located, January 7, 1937. Cold. The heavy sound of Japanese armored cars, out on patrol down the busy shopping streets that flank the Forbidden City. (Japan would occupy the city seven months later.) The martial sounds and the crowds seem not to distract a couple of teenage girls as they make their plans to go skating for an hour or so, under the arc lights of the newly constructed French ice rink. They leave open the question of where they might meet later in the evening. There are parents to be alerted, supper to be eaten. Notes have been exchanged, hints dropped. Perhaps there will be time, a little later, for a girl to have a bit of an adventure with some fellow students, or perhaps with a few older men, who seem to think this is a good evening for a diversion.

Certainly that would be a change from the girls’ accustomed rhythms, dictated by the prescribed curriculum of Latin texts and the polite tyranny of their dowdy boarding school uniforms. But even with all the knowledge they have managed to store up in their short lives so far, none of this little group could have had the faintest idea how bad things were going to get. And least of all, perhaps, a girl called Pamela, destined within the next few hours to be savagely bludgeoned to death.

Over the last century and a half, scores of books have been written about the foreigners who chose—or tried—to live in China: they include teachers and financiers, traders and political agents, diplomats and musicians, scientists and military specialists, missionaries and surgeons. But in this book Paul French tells us a different kind of story about the sojourners and offers us a new frame in which to place them: his tale takes us into the worlds of the foreigners who had settled in Peking during the 1930s and created new lives for themselves, even if lives of a fragile or fleeting kind, on the edges of society, or else below it altogether.

Many lived in the “run-down lodging houses” that were jammed on the edges of Peking’s narrow twisting alleys. They were a constantly renewable and derelict class, living on tips or chance encounters, whose members “found work as doormen, barmen, croupiers, prostitutes and pimps.” French calls them “semi-destitute” foreigners. But not everyone in this uncertain world was on the skids: some had long-standing ties of family and residence; for this was a world of shifting associations, “from professionals to the destitute, from ostensibly upstanding members of Peking’s foreign community to those with lengthy criminal records.”

French shows how lodgings did not necessarily determine social class or comparative wealth: some “lived in well-appointed apartment buildings” and “others in cheap flophouses.” Others chose not to have their lodgings known, or lived in both zones, depending on necessity or chance. They could be from anywhere in the world, but perhaps most were American, British, Canadian, or Italian. We meet an American dentist who lived in a luxury apartment in the Legation Quarter, after his wife had left him, taking their three children with her. There was an Italian doctor, kept busy by squads of unruly Italian sailors. The quarter was technically reserved for diplomatic or administrative personnel, but no one could control what happened at the parties there. And if one wanted greater privacy, there were also temples in the beautiful Western Hills that could be rented, with no questions asked, and no prying eyes. Increasing numbers of women who originally had been White Russian fugitives from the Bolsheviks or Jewish refugees from Germany and Central Europe were feeding on the opportunities in China as the rest of the world grew grimmer.

Midnight in Peking is both a detective story and a social history, and therefore—as it should—always keeps the hunt for Pamela’s killers somewhere near the center of the narrative. But French never forgets the victim and the little group of family members whose lives lay at the center of the tragedy, and he is a wonderfully dexterous guide in presenting the intersecting nature of the murder evidence with the characters’ own lives and experiences as he unearths it. Most especially is this true in the portrayal of Edward Theodore Chalmers Werner, the father of the murdered young woman. So detailed is French’s portrayal of this tragic but difficult man that it will, I feel, give Werner an enduring place in the often prosaic annals of conventional diplomatic history, and in the even murkier internal politics of the British foreign service.

Edward Werner was born in New Zealand in 1864, to a Prussian father and an English mother. His childhood was filled with travel and adventures, and he became at home in several languages. After his father’s death and several years in the academically excellent Tonbridge School, Werner sat for the British foreign service examinations, earning a scholarship for two years of intensive study in Peking as a student interpreter. Excelling at Chinese, Werner was appointed to a series of China postings during the 1890s and 1900s, the most prestigious of which was as the consul general of Fuzhou on the east China coast. He retired from the service in 1914, at the age of fifty.

Advertisement

During his close to thirty years of consular service in China, Werner developed a mixed reputation in the various Chinese ports and commercial cities where he served, and his transfers between posts were often close to being demotions, for he was clearly unpopular and at times downright exasperating or stubborn, and the mediocrity of the cities or river towns where he served is a kind of roster of potential failure; loneliness and depression often came with such postings.

Nevertheless, instead of returning at once to England and the quiet life of a former diplomat, as most of his contemporaries had done, Werner married in 1911 and subsequently moved with his wife Gladys to a rented house in Peking, determined to concentrate on a life of Chinese scholarship. In 1919, the couple was still childless, and decided to adopt a child. They chose a little girl from a Western birth mother, who had been raised in a Peking orphanage, whom they named Pamela. According to the birth certificate issued by the British consulate, Pamela’s estimated date of birth had been February 7, 1917.

Gladys herself soon fell seriously ill, and was sent to the United States for treatment, but with no effect. She died after returning to Peking in 1922 (according to her doctors, from meningitis). Pamela was then just five. Again, Werner did not attempt to leave China for life in Europe or the United States but instead decided to stay in China with his daughter, to enroll her in local Peking schools—her Chinese-language skills were already considerable—and to continue with his own ambitious program of travel, research, and writing about China. His courtyard house, rented from a Chinese landlord, was elegantly (if rather heavily) furnished, with spacious grounds and gardens. It stood on a quiet street quite near the British Legation Quarter, but outside the perimeter protected by the British.

Father and daughter lived there together for many years, and it was not far from this rented home, in a deserted stretch of wasteland below the southeast watch tower of the old city wall protecting the former imperial city, that a scholarly Chinese dawn stroller taking his caged songbird for a walk saw Pamela’s dead body lying in a ditch. Her face and body had been so hideously mutilated that the identity of the corpse could only be established by means of her ripped clothing and her expensive and elegant wristwatch, suggesting that she was not killed for material gain. It was just one month before what would have been her twentieth birthday. Werner was seventy-two.

That the case was never officially solved seems remarkable, especially in view of the savagery of the crime, Werner’s status as a retired diplomat and consul, his reputation as a prominent scholar, his excellent knowledge of the Chinese language, and his intimate knowledge of the city, through which he took long walks almost every day. Also, though Pamela’s circle of friends was still comparatively limited, she would have been a striking sight in Peking because of her blond hair and gray eyes. Like her adoptive father, she too was adventurous, was fluent in Chinese, knew the worlds of street vendors and stall owners, and had boldly ridden her bicycle even in the unlighted lanes and byways of the old city quarters.

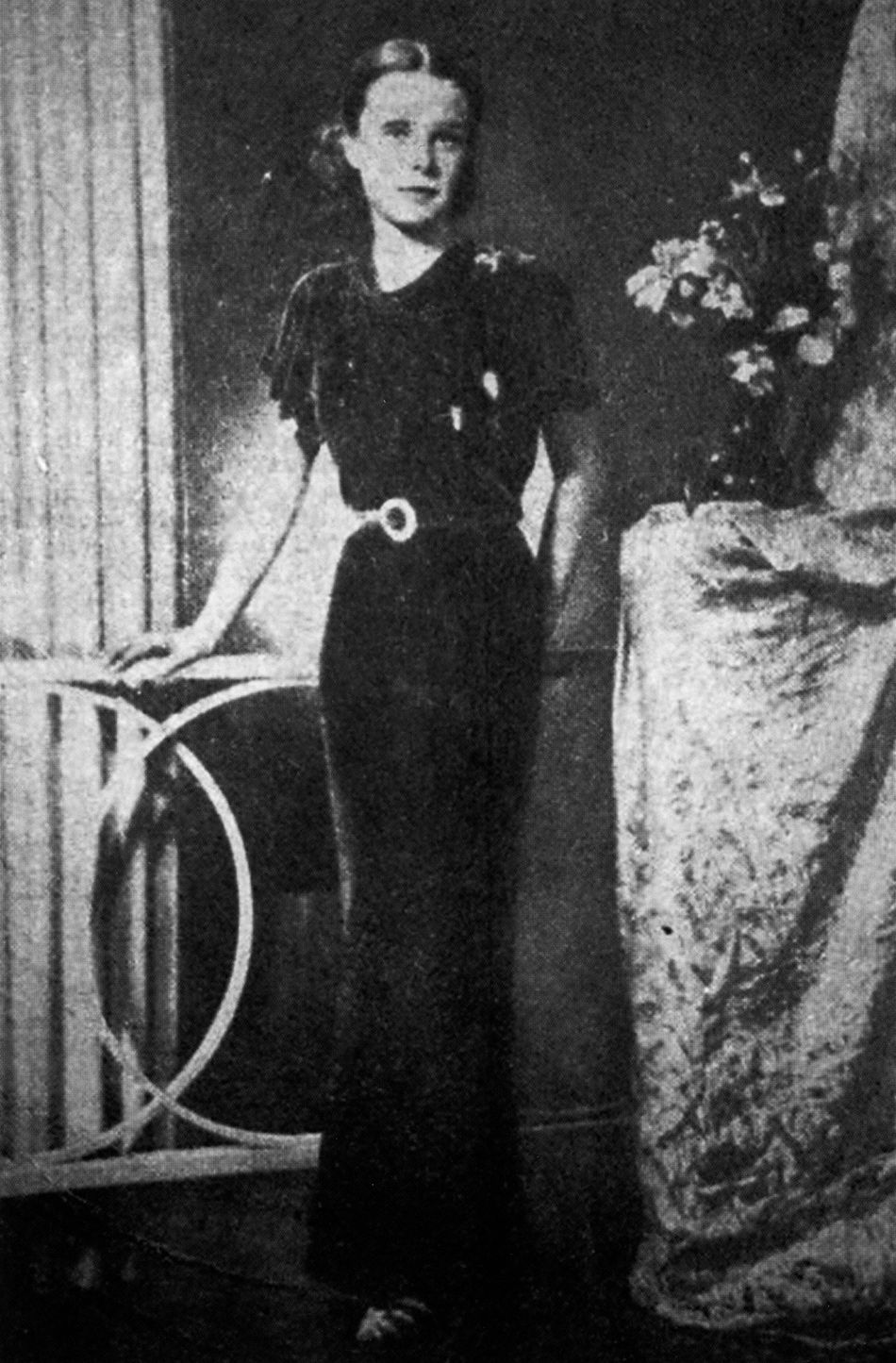

But somehow, whether we focus on the daughter or the father, we run up against something elusive. Pamela was articulate and adventurous, true, but perhaps too adventurous. She had been enrolled by her father in a wide range of schools in Peking, and later in Tientsin, but seems to have been pressured by the schools themselves to withdraw, either because of disciplinary problems or because she had a reputation for risky behavior with her boyfriends and even her teachers. In her indiscretions she teetered visibly between two worlds—that of the schoolgirl in a short tartan skirt who loved ice skating, and that of the carefully coiffed young lady in a full-length black gown who wore, prominently visible, the striking platinum and diamond wristwatch costing hundreds of pounds that she had bought for herself in memory of her dead mother. (Pamela’s mother had left her a trust fund of several thousand dollars, so while not financially independent she still had a comfortable buffer against the encroaching world.)

Advertisement

Thus she could indulge smaller whims without a thought: for example, having enjoyed her skating at the new French rink, she had at once taken out a membership. The blood-stained member’s card was subsequently found near her body. Somewhere along the line, she had also become familiar enough with the world of grown-up maneuvering to leave or receive little notes held in her name by the concierges of the nearby luxury hotels like the Grand Hôtel des Wagons Lits in walking distance from the Peking railway station.

Precious for the historian are the many threads that link Pamela’s everyday Peking world to that of the “ex-pat” day and boarding schools that gave rhythm to the days of many young people at the time, mainly to wealthier Westerners, but also to affluent Chinese and Koreans. Amid all the possible diversions there still had to be the daily lessons, needed to prepare for Oxford and Cambridge entrance examinations. French has made an absorbing case study of the Tientsin day and boarding school where Pamela and her friends spent several years. Clearly the headmaster of her Tientsin school—who had learned his craft in Rangoon and Nigeria as his preparation for China—was vicious and abusive, sadistically drawn to caning as a punishment both for girl students and for boys. Werner withdrew Pamela from the school after hearing of the headmaster’s sexual innuendoes, or perhaps of his practices. The headmaster was abruptly fired, we learn, and shipped back to England with his family. The new headmaster, in an article in the school paper, warned that in this world “East of Suez” truth was “easily twisted into scandal.”

As for Pamela’s father, he made a self-insulating cult of his loneliness. It may indeed have been true that he disliked most people he met, and that he made no attempt to conceal it. His rudeness was sincere, and life had not been easy for him. In some of the darker passages, Werner calls to mind the crazed sinologist Peter Kien in Elias Canetti’s wondrous novel Auto da Fé. Like Kien, Werner spent much of his life with his Chinese texts in his spacious study, tracking, in his case, the arcane terms in early texts on Chinese mythology, his great passion, and carefully collating their variants and shifting popular and scholarly usages. Werner made long treks on his own to China’s border regions, seeking linguistic clues and filling in the gaps in his knowledge, leaving Pamela alone at the house—albeit with several trusted servants and her own former amah—a combination nanny and maid—to keep an eye on her.

Though Werner’s scholarly work was acknowledged by contemporary Chinese university colleagues, and he may have been pleased by some local recognition, he nevertheless seems to have been a loner in a broad sense, unable to look past his and his daughter’s current lives to view the scenes beyond. In the preface to his celebrated Dictionary of Chinese Mythology, published in 1932, five years before the murder of his daughter, he wrote that his work aspired to be nothing less than “A Who’s Who of the Chinese Otherworld.” And the Otherworld, he continued, “so far from being a remote and almost inaccessible Heaven, is in fact a duplicate of this world, plus ancestral hierarchies of gods and goddesses growing ever less distinct as we look further back into the misty depths of antiquity.”

Werner seems to have made no attempt to mingle with the other members of the loose-knit community of China scholars in the Legation area, even though they had regular meetings to discuss scholarly problems that might have interested him. He could have walked there in under half an hour, or rented a rickshaw for almost nothing. If Werner had wanted even a faint whiff of politics, then by a small but strange coincidence the house two down the street from his and Pamela’s had been rented by the ebullient journalist Edgar Snow, who had allowed it to be used for Communist Party meetings, and whose absorbing accounts of Mao Zedong’s long march were just dominating the world’s headlines.

The broad political setting is not essential—at least not in any comprehensive way—to the telling of this story, but one other matter is worth particular attention. For besides the actual killers, whom French believes he has tracked down with Werner’s own posthumous archival help, we have one other major actor—or set of actors. These are the professional British diplomats who ran the little administrative empire known as the Legation Quarter, and who continued to hold on to the dimly remembered days of nineteenth-century prestige. Smugly and consistently, the British authorities in China interfered in Pamela’s case, suppressing or distorting evidence, lying blatantly to protect their own police forces, and snobbishly deflecting all routes of inquiry that might have allowed the Chinese police authorities to analyze and solve their own case in their own way. (The Foreign Office files and correspondence on the case, although the clues in them were not followed up, were still carefully classified and preserved in the archives at Kew, along with Werner’s lengthy letters, to await French’s analysis and to take the case either to a solution or at least to a higher stage.)

Whether or not French has managed to fully solve the case of Pamela, as he believes he has, his book is full of valuable swerves and tangents. For example, Midnight in Peking serves as a tightly orchestrated study of the little streets and alleys that crisscrossed the southeast corner of old Peking. It is hard not to be brought fully into the tale when the streets come so clearly into focus, as we get to remember certain street and house numbers that slowly, with familiarity, toll like a knell through the actions and plans of the characters in French’s book, through their schemes and their (not always correct) solutions. We remember how long x takes to get to y by foot, by bike, and by rickshaw, and where in the city one man’s moves were obvious, and when they were carefully concealed. We too traverse the same lanes day by day, and we too want the protection of darkness as often as we seek its aid. The story draws much of its power from the fact that Pamela is our guide until her death, and that thereafter it is Werner in his trusty old gabardine coat and his wrap-around sunglasses as his protection from the glare and the dust who stops us from losing our way.

However we define him, Werner was not the kind of man who made people want to help when he was in trouble. He infuriated the British, failed to get in close touch with the Chinese officers assigned to the case, gave his own contradictory press conferences on the steps of the regional substation, and rooted around the probable crime scenes without permission. One can find many reasons for his attitudes, but the fact remains that it was only when the case had grown cold that Werner was willing to make the deep commitment to bring his linguistic and scholarly skills to the fore, and to concentrate his energies on reassembling the broken shards of evidence left lying around by incompetent bureaucrats or duplicitous police officers.

The results of those years of hunting are the coda to French’s book, and it becomes the reader’s task to separate fact from hypothesis. The case back in January 1937 seemed so clear that surely the guilty killers would be caught and punished. But that has not happened. Werner stayed on in China until 1951, when he was almost ninety. If historians have a paradise maybe he is there, arguing still, and irritating everyone, for the right reasons.

This Issue

March 21, 2013

When the Jihad Came to Mali

Homunculism

The Noble Dreams of Piero