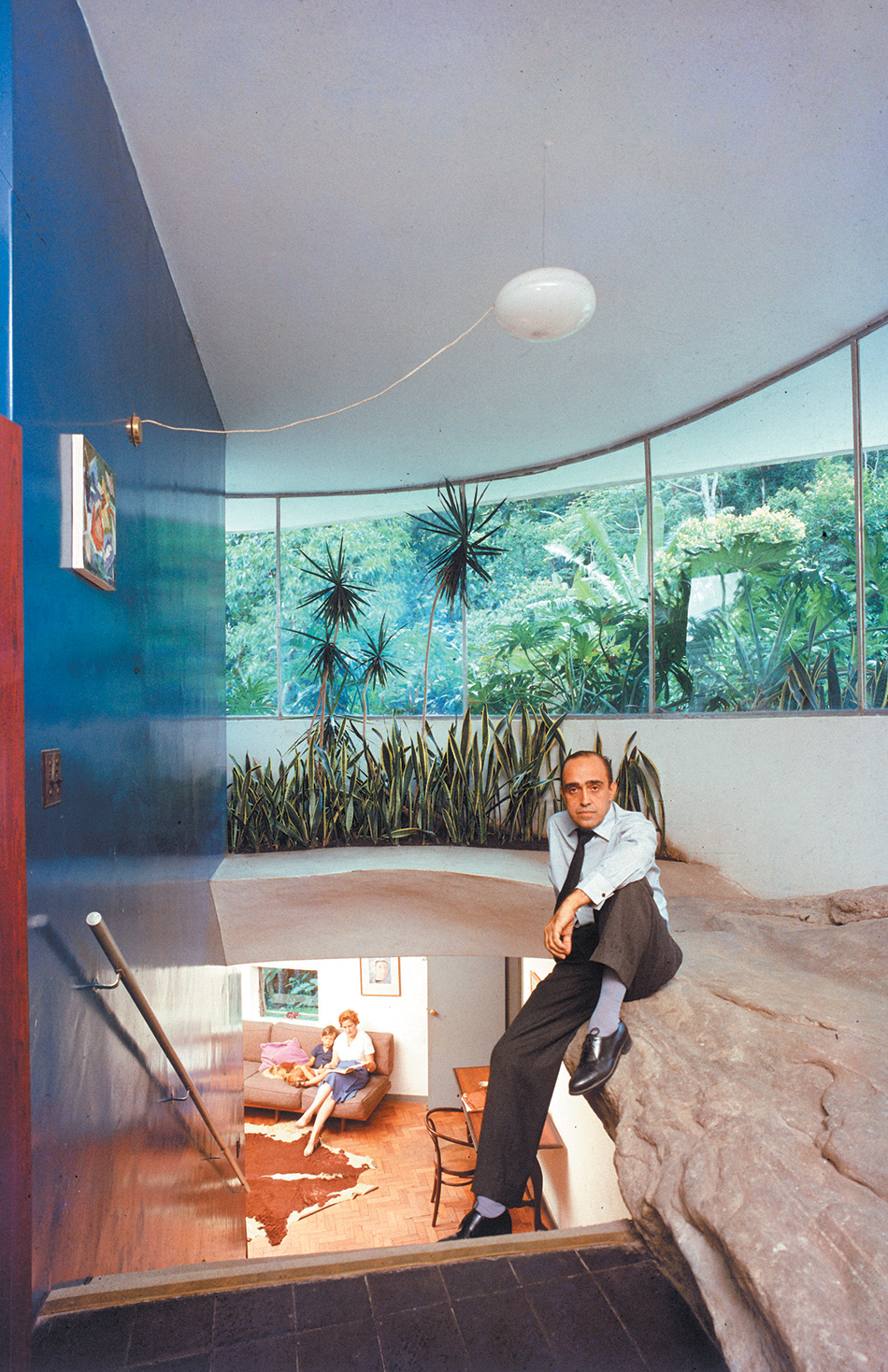

1.

When Oscar Niemeyer died on December 5, 2012, ten days before his 105th birthday, he was universally regarded as the very last of the twentieth century’s major architectural masters, an astonishing survivor whose most famous accomplishment, Brasília, was the climactic episode of utopian High Modern urbanism. That logistical miracle and social adventure took just three and a half years from conception to completion, yet fell far short of its transformative intentions. It was the most audacious planning scheme in a century that saw the creation of several other impressive capital cities prompted by the waning of colonialism and the ascent of nationalism, including Walter Burley Griffin’s Canberra in Australia (1912–1920), Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker’s administrative nexus of the British Raj at New Delhi (1913–1931), and Le Corbusier’s regional seat for the Indian Punjab at Chandigarh (1952–1959).

Brasília, laid out by Niemeyer’s mentor Lúcio Costa in 1957 and built principally by Niemeyer from 1958 to 1960, would have been enough to secure the architect’s place in history. Yet posthumous recapitulations of his epochal career remind us that during the two decades that preceded this colossal undertaking—especially the early 1940s, when South America remained free from involvement in World War II and thus was able to build with abandon—Niemeyer stood at the very peak of architectural innovation and invention. In those dark times he almost single-handedly upheld life-affirming values counter to the industrialized mayhem being visited on so much of mankind.

Niemeyer’s work has rightly been likened to Brazilian music: the swaying lines and swelling contours of his biomorphic 1940s designs evoke the samba, the sensuous and insinuating dance that encapsulates that country’s vibrant multiracial mix and subliminal sexuality. The cooler syncopations of bossa nova were echoed in the measured visual rhythms of the architect’s more self-consciously elegant Brasília phase of the late 1950s and early 1960s. His work was then contemporaneous with the emergence of the “new beat” that caused a global sensation just as fantastic images of his dream-come-true city were splashed across the international press (exuding a visual charisma similarly conveyed by the striking color photos in Philip Jodidio’s introductory Oscar Niemeyer).

Oscar Ribeiro de Almeida Niemeyer Soares Filho was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1907 into a prominent upper-middle-class family of German descent; his father was a typographer and one grandfather a supreme court justice. In 1929 he entered the National School of Fine Arts in Rio and studied architecture under Costa, who, along with his partner, the Russian émigré Gregori Warchavchik, was a founding father of Brazilian modernism. Their seminal work, which helped establish their country as a force in world design, is authoritatively presented in Hugo Segawa’s thorough new survey, Architecture of Brazil, 1900–1990.

Upon receiving his architecture degree in 1934, Niemeyer joined the Costa firm. Two years later Costa won the commission for a new Ministry of Education and Health headquarters in Rio and invited Le Corbusier, who had lectured to great acclaim in the city in 1929, to serve as design adviser. Forward-thinking Brazilian architects eagerly embraced Le Corbusier’s precepts, particularly his use of reinforced concrete, which is cheaper, more adaptable to tropical settings, and offers greater sculptural plasticity than conventional steel-frame construction. During his first visit to Brazil, Le Corbusier urged his young coprofessionals to take freely from his work, but when Niemeyer showed that he was a bit too adept at improving on those prototypes, the Swiss-French master, ever wary of potential rivals, lashed out.

One big problem in adapting Le Corbusier’s slab-like tower schemes to warmer regions was providing climate control at a time when mechanical air-conditioning was still in its infancy. In his unbuilt Plan Obus of 1933 for Algiers, Le Corbusier specified louver-like brises-soleils—sun-breakers—for the scheme’s exposed façades, but he had still not executed any by the time Niemeyer beat him to the punch at the Rio ministry. The young architect also raised the slab’s ground-level piloti columns to a more monumental height of thirty feet, which resulted in a work that by common consent out-Corbusiered Le Corbusier.

From the outset Niemeyer favored a design element found only occasionally in his idol’s pre–1930 oeuvre: the curve. As he wrote:

I am not attracted to [right] angles or to the straight line, hard and inflexible, created by man. I am attracted to free-flowing, sensual curves. The curves that I find in the mountains of my country, in the sinuousness of its rivers, in the waves of the ocean, and on the body of the beloved woman. Curves make up the entire Universe, the curved Universe of Einstein.

Niemeyer found his ideal horticultural counterpart in the landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx (1909–1994), who created strong biomorphic ground patterns in large monochromatic beds of plants (analogous to the free-form compositions of Jean Arp, Alexander Calder, Joan Miró, and other Surrealist artists of the 1930s). A gifted botanist, Burle Marx domesticated many native plant species, more than thirty of which now bear his name. He fully integrated the natural and the manmade with indoor–outdoor water features and other illusionistic devices. Thanks to his work, Niemeyer’s buildings achieved an aura of Edenic wonder unmatched in modern times.

Advertisement

Costa and Niemeyer collaborated on the Brazilian Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, the indisputable architectural hit of the exposition (which also featured Alvar Aalto’s now legendary Finnish Pavilion). This exotic modernist efflorescence dazzled visitors with its languorously attenuated ramps, delightfully ambiguous transitions between exterior and interior, and a pond designed by Burle Marx to display the gigantic Amazonian water lily Victoria regia (which had inspired Joseph Paxton’s ridged glazing at London’s Crystal Palace of 1850–1851). Niemeyer’s remarkable early designs were likewise highlights of the Museum of Modern Art’s avidly received 1943 survey “Brazil Builds,” an upbeat escapist interlude during America’s architecturally deprived war years.

2.

The commission that fully displayed Niemeyer’s individual genius for the first time was his stunning complex of small buildings at Pampulha, a prosperous new suburb of Belo Horizonte, capital of Brazil’s mineral-rich Minas Gerais state. Here in 1940 Juscelino Kubitschek—a physician-turned-leftist-politician known as the city’s “hurricane mayor” because of his whirlwind initiatives—began his two decades as Niemeyer’s greatest champion. Kubitschek’s urge to build big—which he continued as governor of Minas Gerais (1950–1955) and finally as president of Brazil (1956–1961)—makes François Mitterrand’s grands projets of 1981–1998 seem somewhat underreaching. (In 1964, after the coup by the right-wing dictator General Castelo Branco, Niemeyer went into exile for seventeen years.)

In hiring Niemeyer to design a series of recreational public buildings around a new man-made lake at Pampulha, Kubitschek caught the architect at the very peak of his powers. Positioned at spacious intervals around the amoeba-like shoreline are the Casino, House of Dance, Yacht Club, Golf Club, and Church of Saint Francis of Assisi. In particular, the Casino of 1940–1943 (converted to an art gallery when Brazil outlawed gambling in 1946) is a spatial marvel. Set on a gently sloping waterside bank, this two-story structure comprises a square ground-floor entry defined by an equilateral grid of thin pilotis (much like those in Corbusier’s Villa Savoye of 1928–1931 in Poissy, France) with window walls that dematerialize the concrete-framed exterior.

Atop this simple plinth is a second rectangular level containing the gaming room and, within an ovoid appendage that billows out toward the lake, a restaurant tiered with multiple concentric levels to maximize seeing and being seen. To increase the efficiency of the Casino’s several leisure functions—dining, dancing, and gambling—Niemeyer devised an ingenious tripartite circulation system with separate stairways, ramps, and catwalks so that patrons, entertainers, and service staff could pursue their appointed activities without colliding.

We are now aware that the interiors of early modernist buildings were less austere and colorless than has been imagined, but the Pampulha Casino was more hedonistic than most European pleasure domes of the interwar period. Here, amid brightly hued, alluringly fragrant gardens laid out by Burle Marx, Niemeyer combined walls paneled in onyx, exotic native woods, and rose-tinted mirror; floors of parquet and polished travertine; slender stainless-steel-clad columns; hangings and upholstery of organza, satin, taffeta, and tulle; and a circular, translucent etched-glass dance floor lit from below—all of which together conjured what Cole Porter memorably called “a night of tropical splendor.”

As if to give habitués of this nocturnal adult playground remission from its many occasions of sin, the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi of 1940–1942 stood nearby to offer absolution—or would have, had not conservative Catholic officials, offended by the chapel’s freewheeling form and frank sensuality, refused to consecrate it until 1959, by which time Niemeyer had become a national culture hero. His church features a lateral line-up of four parabolic arches formed from thin concrete shells (faced with a tile mural of scenes from the life of the saint by Cândido Portinari); the arches suggest the rolling contours of a mountain range, or perhaps a recumbent female nude. The similarly vaulted nave, which telescopes into the arch of the high altar like the stem of the letter T, reiterates the traditional format of Baroque churches in Minas Gerais, as does this little gem’s extravagant sculptural quality.

In 1946, a year after the United Nations was founded, John D. Rockefeller Jr. donated $8 million for the purchase of a sixteen-acre parcel bordering the East River in midtown Manhattan as the organization’s permanent home. The honor of designing the new headquarters was deemed too great for any one member nation, so an international Board of Design, which included Le Corbusier and Niemeyer, was established under the direction of Wallace K. Harrison, the Rockefeller family’s longtime architectural factotum. This complicated saga is revealed in illuminating behind-the-scenes detail in A Workshop for Peace: Designing the United Nations Headquarters by George A. Dudley, an architectural assistant of Harrison’s charged with documenting the proceedings, a veritable master class in the pitfalls of design-by-committee.1

Advertisement

Though the forty-year-old Niemeyer was the youngest among the design team, his schematic outline—essentially the UN complex as we now know it, dominated by the slender slab of the Secretariat Building set parallel to the river—caused a sensation among his collaborators. As Dudley recorded:

It literally took our breath away to see the simple plane of the site kept wide open from First Avenue to the [East] River, only three structures on it, standing free, a fourth lying low behind them along the river’s edge….

The comparison between Le Corbusier’s heavy block and Niemeyer’s startling, elegantly articulated composition seemed to me to be in everyone’s mind. As different as night and day, the heaviness of the block seemed to close the whole site, while in Niemeyer’s refreshing scheme the site was open, a grand space with a clean base for the modest masses standing in it.

Le Corbusier disagreed: in his notebook he labeled a thumbnail sketch of his own proposal “beau” and Niemeyer’s “médiôcre” [sic], though in fact it was quite the opposite. As the oldest, most eminent member of the panel, Le Corbusier pulled rank and at one meeting “blew his top and shouted, ‘He’s just a young man; that scheme isn’t from a mature architect.’” Though Le Corbusier could not get his own proposal accepted, he cowed Niemeyer into altering his configuration, eliminating the open areas between buildings Niemeyer called for, and thereby grievously diminished its spatial qualities. The execution of the ensemble was handed over to Harrison and his partner, Max Abramovitz, whose lackluster detailing further diluted Niemeyer’s exhilarating initial vision. Though the participants had agreed that the UN Headquarters would be credited as a group effort, Le Corbusier tried to claim sole authorship, and evidently altered and backdated his sketches to support that fraudulent impression. Yet even in its compromised final state, this eloquent and hopeful midcentury landmark remains most identifiably the conceptual work of Niemeyer.

3.

Though the idea of relocating Brazil’s government from the old Portuguese colonial capital of Rio to a virgin site deep within the hinterlands arose several centuries ago, Brasília’s origin myth—a miraculous tale disseminated by Kubitschek to spur popular support for his quixotic $40 billion endeavor—is of more recent vintage. According to this mystical account, in 1883 an Italian missionary priest, Giovanni Bosco (later canonized as Saint John Bosco and now patron saint of Brasília), had a dream in which he traveled by train through the Andes to Rio accompanied by an angelic companion. As Bosco recalled his vision:

Between the fifteenth and twentieth degrees of latitude, there was a long and wide stretch of land which arose at a point where a lake was forming. Then a voice said repeatedly:…there will appear in this place the Promised Land, flowing with milk and honey.

Niemeyer, a lifelong atheist, framed the argument for the move to land at the prophesied latitude of 15° 45’ in more political terms:

Rio is a lavish show-window which hides from public view the poor, backward, and forgotten…. The seat of government must be established in the heart of Brazil’s vast territory, so that it surveys the whole national panorama, so that it will be within reach of all the classes and all the regions.

Yet Brasília turned out to be anything but egalitarian, and Niemeyer eventually confessed that this putative everyman’s utopia “was a city constructed as a showcase of capitalism—everything for a few on a world stage.”

The rapid and economical construction of the new capital was aided by a drought that in early 1958 propelled ten thousand out-of-work laborers to the building site. The refugees created instant favelas—Rio-style shantytowns that Brasília was meant to eradicate—that grew into the ring of impoverished satellite communities that still encircle the capital, an island of bureaucratic privilege within a sea of squalor. (Only in 1985 did Costa add a group of low-cost residential units on the edge of Brasília.)

Kubitschek insisted that an international jury preside over a competition for Brasília’s master plan, which infuriated Le Corbusier, who deeply coveted the job and denounced such unseemly auditioning as “democratic cowardice.” He persuaded President de Gaulle to intervene on his behalf with the Brazilian president but to no avail. As many commentators have noted, Costa’s airplane-shaped plano piloto (pilot plan)—with a 3.75-mile-long monumental axis that comprises the “fuselage” and a perpendicular eight-mile-long residential axis that forms the curving “wings”—is a distorted version of Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse (Radiant City) of 1924, his radical vision of an ideal metropolis dominated by skyscrapers widely spaced amid sweeping greenswards and serviced by broad automobile thoroughfares.

Flanking Costa’s monumental axis are Niemeyer’s two rows of identical ten-story horizontal-slab governmental ministry buildings—ten on one side, seven on the other—ranged in eerily monotonous ranks like the German architect Ludwig Hilberseimer’s unexecuted Hochhausstadt (High-Rise City) project of 1924. In these buildings, there is no hint of the “free-flowing, sensual curves” Niemeyer had earlier celebrated. Furthermore, the structures were environmentally disastrous. Lacking brises-soleils and air-conditioning, they became so unbearably hot that at least one government minister kept offices on opposite exposures and moved between them at noon.

At the very “nose” of this virtual aircraft stands the triangular Plaza of the Three Powers, an architectural embodiment of the executive, judicial, and legislative triad. Each branch is accorded its own instantly identifiable architectural presence. The two legislative bodies are signified by paired, shallow domes that surmount a long rectangular base: the cupola of the Senate, and the Chamber of Deputies’ bowl-like reversal of that form. Centered behind them rise the twin towers of the Congressional Secretariat, two parallel twenty-eight-story slabs linked midway by a flying bridge that completes the outline of a mammoth capital H. The adjacent presidential office block and Supreme Court building are similar glass-walled boxes, each with two elevations enlivened by flaring, fin-like marble colonnades.

The loveliest of Brasília’s structures is the presidential residence, the poetically named Palácio da Alvorada (Palace of the Dawn) of 1956–1958, a transparent, rectilinear Miesian pavilion with screenlike curvilinear embellishments on its long sides. These white-marble colonnades of swooping, bladelike forms bring to mind an upside-down sequence of arches and were instantly dubbed “Oscar’s cardiogram.” Yet despite many crude and debasing knockoffs, this graceful attempt to recast an essential Classical motif in modern structures has endured the test of time thanks to its designer’s brilliant sense of line and proportion.

Brasília’s most distinctive architectural form is Niemeyer’s Metropolitan Cathedral of Our Lady of Aparecida (1958–1971), a dramatic circular arrangement of eighteen boomerang-shaped concrete columns that are joined by clear- and stained-glass panels and flare upward like a chalice, a crown of thorns, or, more irreverently, a crown roast of lamb—though perhaps the best analogy is a bound sheaf of wheat, a motif associated since ancient times with the Eucharist and salvation. Set to one side of the monumental axis, the church is entered through a subterranean tunnel that intensifies a sensation of soaring, light-flooded uplift as one emerges into the dome-like sanctuary.

4.

In 1945, Niemeyer joined the recently formed Brazilian Communist Party after giving shelter to opponents of the Vargas dictatorship in his house, which he soon turned over to the Party. His Party membership did not debar him from coming to the US to work on the UN scheme—representatives of the organization’s Communist member states enjoyed diplomatic immunity—but it did cost him other work here. Invited to teach at Yale in 1946, he was denied an entry visa, and when he was offered the deanship of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in 1953 he had to decline on similar grounds, as happened yet again in 1967 when he was asked to design a business center near Miami. His only built American work apart from the UN is the Strick house of 1963 in Santa Monica, California, a breezy, low-slung pavilion commissioned by a Hollywood movie director with leftist sympathies and supervised by the architect in absentia. Another California project, a Montecito retreat for the art collectors Burton and Emily Tremaine, came to nought.

Offered a French passport by de Gaulle in 1967, Niemeyer resettled in Paris, where he opened an office and produced large-scale schemes for international clients, including headquarters for the publisher Mondadori in Segrate, Italy (1968–1975), and the University of Constantine of Algeria (1969–1972). His abiding political allegiance was demonstrated by his French Communist Party headquarters of 1967–1980 in Paris—an undulating mid-rise slab that adjoins a shallow concrete dome atop a below-street-level conference hall rather like the UN General Assembly Chamber.

Niemeyer’s extraordinary longevity allowed him to witness the cyclical ups and downs of artistic reputation come full circle within his own lifetime. The ecstatic reception that greeted Brasília’s inauguration on April 21, 1960, soon gave way to well-deserved dissections of its serious failings as socially imaginative planning. No critique has been more incisive than James Holston’s The Modernist City: An Anthropological Critique of Brasília, which skewers the scheme’s humanitarian aspirations toward creating a classless society while in fact it abets further division between rich and poor.2 As Postmodernist design began its brief ascendance in the 1970s, Brasília’s Space Age aesthetic was derided by neo-traditionalists, and its Corbusian grandiosity denounced by proponents of the neoconservative New Urbanism movement.

But as attitudes shifted yet again, the 1988 Pritzker Prize was jointly given to Niemeyer and Gordon Bunshaft—the first dual conferral of that award—in what was widely interpreted as a rebuke to Postmodernism after its adherents James Stirling and Hans Hollein had been thus honored. Accolades continued to mount as Niemeyer grew older and older; in 2003 he was asked to design that summer’s temporary pavilion at London’s Serpentine Gallery in Hyde Park, a sure index of contemporary architectural hipness.

Niemeyer’s early ecological awareness, for the most part tradition-based and low-tech, has brought his logical solutions for building in hot climates to the forefront (though Brasília is hardly a model of energy efficiency). New interest in that aspect of Niemeyer’s architecture has concentrated on his unexecuted scheme for the O Cruzeiro Publishing Plant and Headquarters of 1949 in Rio—a ten-story box with adjustable horizontal light baffles like giant Venetian blinds. This project was chosen among twenty-five works (including designs by Aalto, Le Corbusier, and Frank Lloyd Wright) for “Lessons from Modernism: Environmental Design Considerations in 20th Century Architecture, 1925–1970,” a timely and thoughtful exhibition organized by the Institute for Sustainable Design at New York’s Cooper Union.

Niemeyer’s last works are far from his best, but that has not affected their popularity. His white disc-shaped Niterói Contemporary Art Museum of 1991–1996, perched atop a rocky promontory overlooking Guanaraba Bay and Rio de Janeiro to the west, has been a runaway success as a tourist attraction. But the Niterói museum’s curves are not nearly so felicitous as those of the architect’s earlier designs, and one could well imagine that this awkward flying saucer was denied landing permission at Brasília and forced to alight here instead.

Niemeyer led an eight-decade-long samba through the building art, a joyous journey that gave the world some of its liveliest modern landmarks. Samba—which attains its annual climacteric during the pre-Lenten bacchanal of Carnaval—is deeply subversive yet also an essential expression of Brazil’s inner nature. A cardinal trait of Carnaval is its inversion of societal norms, a once-a-year world-turned-upside-down when paupers can be princes, saints can be sinners, and the upright can be lowdown. Inversion is also a recurrent theme in Niemeyer’s architecture, as seen in his juxtaposition of a casino and a church at Pampulha; the topsy-turvy pyramid of his unbuilt Caracas Museum of Modern Art of 1955; the paired up-and-down domes at Brasília; and above all his undulating line—a “carnivalization” provocatively analyzed in Styliane Philippou’s richly detailed Oscar Niemeyer: Curves of Irreverence, the finest study yet of this subtly anarchic figure.3

Though Niemeyer is often characterized as a maverick whose preference for the curve instead of the straight line and right angle set him in diametric opposition to the restrictive orthodoxies of Modernism, he in fact asserted not so much a contrarian as a parallel, liberating alternative. During his early prime, Niemeyer commanded creative powers that were the tropical equivalent of his Nordic contemporary Aalto, who also asserted that sensuousness and delight have as much a place in modern architecture as technical ingenuity, rational simplicity, and intellectual rigor. Charles Jencks has observed that

In many respects the personality and work of Aalto are the inverse of Le Corbusier’s: relaxed and flowing rather than violent and tempestuous and patient rather than outspoken.

The same might be said of Niemeyer vis-à-vis Le Corbusier. The irascible elder architect’s late-career biomorphic redirection derived in no small part from lessons he obviously learned from his more laid-back younger colleague, as can be seen from the erstwhile machine modernist’s more voluptuous handling of architectural mass in his postwar work. Would we have had Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp chapel without Niemeyer’s unabashedly erotic formação de curvas?

Whether Le Corbusier was merely being polite or sincere when he looked out over the newly completed Brasília in 1962 and told Niemeyer, “Bravo, Oscar, bravo!” we will never know. Unquestionably, though, Oscar Niemeyer excelled in his rare fusion of graphic clarity, formal purity, convincing spatial proportion, sensuous dynamism, and visceral immediacy, a mixture unique among his peers during the two decades before and after 1950. His meridian moment of optimistic modernism is likely to be looked back upon with well-merited fondness for years to come.