The Digital Public Library of America, to be launched on April 18, is a project to make the holdings of America’s research libraries, archives, and museums available to all Americans—and eventually to everyone in the world—online and free of charge. How is that possible? In order to answer that question, I would like to describe the first steps and immediate future of the DPLA. But before going into detail, I think it important to stand back and take a broad view of how such an ambitious undertaking fits into the development of what we commonly call an information society.

Speaking broadly, the DPLA represents the confluence of two currents that have shaped American civilization: utopianism and pragmatism. The utopian tendency marked the Republic at its birth, for the United States was produced by a revolution, and revolutions release utopian energy—that is, the conviction that the way things are is not the way they have to be. When things fall apart, violently and by collective action, they create the possibility of putting them back together in a new manner, according to higher principles.

The American revolutionaries drew their inspiration from the Enlightenment—and from other sources, too, including unorthodox varieties of religious experience and bloody-minded convictions about their birthright as free-born Englishmen. Take these ingredients, mix well, and you get the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights—radical assertions of principle that would never make it through Congress today.

Yet the revolutionaries were practical men who had a job to do. When the Articles of Confederation proved inadequate to get it done, they set out to build a more perfect union and began again with a Constitution designed to empower an effective state while at the same time keeping it in check. Checks and balances, the Federalist Papers, sharp elbows in a scramble for wealth and power, never mind about slavery and slave wages. The founders were tough and tough-minded.

How do these two tendencies converge in the Digital Public Library of America? For all its futuristic technology, the DPLA harkens back to the eighteenth century. What could be more utopian than a project to make the cultural heritage of humanity available to all humans? What could be more pragmatic than the designing of a system to link up millions of megabytes and deliver them to readers in the form of easily accessible texts?

Above all, the DPLA expresses an Enlightenment faith in the power of communication. Jefferson and Franklin—the champion of the Library of Congress and the printer turned philosopher-statesman—shared a profound belief that the health of the Republic depended on the free flow of ideas. They knew that the diffusion of ideas depended on the printing press. Yet the technology of printing had hardly changed since the time of Gutenberg, and it was not powerful enough to spread the word throughout a society with a low rate of literacy and a high degree of poverty.

Thanks to the Internet and a pervasive if imperfect system of education, we now can realize the dream of Jefferson and Franklin. We have the technological and economic resources to make all the collections of all our libraries accessible to all our fellow citizens—and to everyone everywhere with access to the World Wide Web. That is the mission of the DPLA.

Put so boldly, it sounds too grand. We can easily get carried away by utopian rhetoric about the library of libraries, the mother of all libraries, the modern Library of Alexandria. To build the DPLA, we must tap the can-do, hands-on, workaday pragmatism of the American tradition. Here I will describe what the DPLA is, what it will offer to the American public at the time of its launch, and what it will become in the near future.

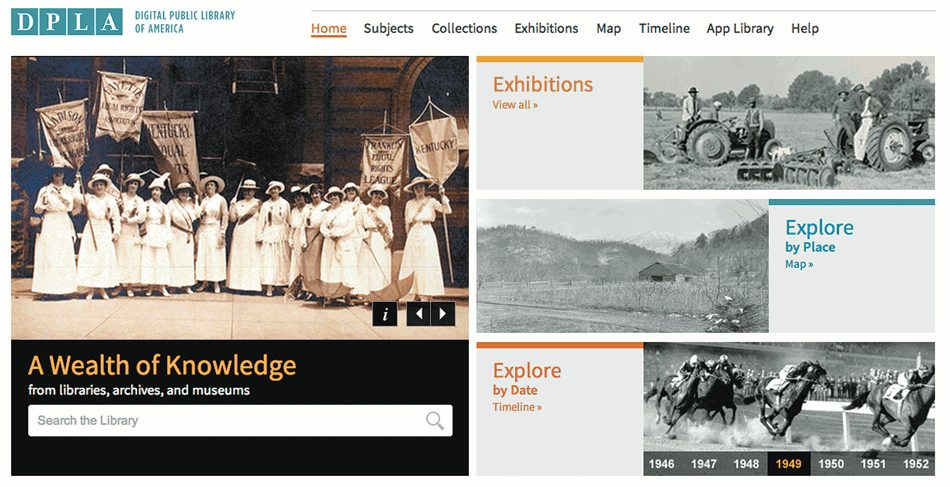

How to think of it? Not as a great edifice topped with a dome and standing on a gigantic database. The DPLA will be a distributed system of electronic content that will make the holdings of public and research libraries, archives, museums, and historical societies available, effortlessly and free of charge, to readers located at every connecting point of the Web. To make it work, we must think big and begin small. At first, the DPLA’s offering will be limited to a rich variety of collections—books, manuscripts, and works of art—that have already been digitized in cultural institutions throughout the country. Around this core it will grow, gradually accumulating material of all kinds until it will function as a national digital library.

The trajectory of its development can be understood from the history of its origin—and it does have a history, although it is not yet three years old. It germinated from a conference held at Harvard on October 1, 2010, a small affair involving forty persons, most of them heads of foundations and libraries. In a letter of invitation, I included a one-page memo about the basic idea: “to make the bulk of world literature available to all citizens free of charge” by creating “a grand coalition of foundations and research libraries.” In retrospect, that sounds suspiciously utopian, but everyone at the meeting agreed that the job was worth doing and that we could get it done.

Advertisement

We also agreed on a short description of it, which by now has become a mission statement. The DPLA, we resolved, would be “an open, distributed network of comprehensive online resources that would draw on the nation’s living heritage from libraries, universities, archives, and museums in order to educate, inform, and empower everyone in the current and future generations.”

Sounds good, you might say, but wasn’t Google already providing this service? True, Google set out bravely to digitize all the books in the world, and it managed to create a gigantic database, which at last count includes 30 million volumes. But along the way it collided with copyright laws and a hostile suit by copyright holders. Google tried to win over the litigants by inviting them to become partners in an even larger project. They agreed on a settlement, which transformed Google’s original enterprise, a search service that would display only short snippets of the books, into a commercial library. By purchasing subscriptions, research libraries would gain access to Google’s database—that is, to digitized copies of the books that they had already provided to Google free of charge and that they now could make available to their readers at a price to be set by Google and its new partners. To some of us, Google Book Search looked like a new monopoly of access to knowledge. To the Southern Federal District Court of New York, it was riddled with so many unacceptable provisions that it could not stand up in law.

After the court’s decision on March 23, 2011, to reject the settlement,* Google’s digital library was effectively dead, although Google can continue to use its database for other purposes, such as agreements with publishers to provide digital copies of their books to customers. The DPLA was not designed to replace Google Book Search; in fact, the designing had begun long before the court’s decision. But the DPLA took inspiration from Google’s bold attempt to digitize entire libraries, and it still hopes to win Google over as an ally in working for the public good. Nonetheless, you might raise another objection: Who authorized this self-appointed group to undertake such an enterprise in the first place?

Answer: no one. We believed that it required private initiative and that it would never get off the ground if we waited for the government to act. Therefore, we appointed a steering committee, a secretariat located in the Berkman Center at Harvard, and six groups scattered around the country, which began to study and debate key issues: governance, finance, technological infrastructure, copyright, the scope and content of the collections, and the audience to be envisioned.

The groups grew and developed a momentum of their own, drawing on voluntary labor; crowdsourcing (the practice of appealing for contributions to an undefined group, usually an online community, as in the case of Wikipedia); and discussion through websites, listservs, open meetings, and highly focused workshops. Hundreds of people became actively involved, and thousands more participated through an endless, noisy debate conducted on the Internet. Plenary meetings in Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and Chicago drew large crowds and a much larger virtual audience, thanks to texting, tweeting, streaming, and other electronic connections. There gradually emerged a sense of community, twenty-first-century style—open, inchoate, virtual, yet real, because held together as a body by an electronic nervous system built into the Web.

This virtual and real discussion took place while groups got down to work. Forty volunteers submitted “betas”—prototypes of the software that the DPLA might use, which were then to be subjected to “beta testing,” a user-based form of review. After several rounds of testing and reworking, a platform was developed that will provide links to content from library collections throughout the country and that will aggregate their metadata—i.e., catalog-type information that identifies digital files and describes their content. The metadata will be aggregated in a repository located in what the designers call the “back end” of the platform, while an application programming interface (API) in the “front end” will make it possible for all kinds of software to transmit content in diverse ways to individual users.

The user-friendly interface will therefore enable any reader—say, a high school student in the Bronx—to consult works that used to be stored on inaccessible shelves or locked up in treasure rooms—say, pamphlets in the Huntington Library of Los Angeles about nullification and secession in the antebellum South. Readers will simply consult the DPLA through its URL, http://dp.la/. They will then be able to search records by entering a title or the name of an author, and they will be connected through the DPLA’s site to the book or other digital object at its home institution. The illustration on page 4 shows what will appear on the user’s screen, although it is just a trial mock-up.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, several of the country’s greatest libraries and museums—among them Harvard, the New York Public Library, and the Smithsonian—are prepared to make a selection of their collections available to the public through the DPLA. Those works will be accessible to everyone online at the launch on April 18, but they are only the beginning of aggregated offerings that will grow organically as far as the budget and copyright laws permit.

Of course, growth must be sustainable. But the greatest foundations in the country have expressed sympathy for the project. Several of them—the Sloan, Arcadia, Knight, and Soros foundations in addition to the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Institute of Museum and Library Services—have financed the first three years of the DPLA’s existence. If a dozen foundations combined forces, allotting a set amount from each to an annual budget, they could create the digital equivalent of the Library of Congress within a decade. And the sponsors naturally hope that the Library of Congress also will participate in the DPLA.

The main impediment to the DPLA’s growth is legal, not financial. Copyright laws could exclude everything published after 1964, most works published after 1923, and some that go back as far as 1873. Court cases during the last few months have opened up the possibility that the fair use provision of the copyright act of 1976 could be extended to make more recent books available for certain purposes, such as service to the visually impaired and some forms of teaching. And if, as expected, the DPLA excludes books that are still selling on the market (most exhaust their commercial viability within a few years), authors and publishers might grant the exercise of their rights to the DPLA.

In any case, we cannot wait for courts to untangle legalities before creating an effective administration. The informal secretariat at Harvard is being replaced by a nonprofit corporation organized according to the 501(c)3 provisions of the tax code. The steering committee has been succeeded by a board of directors. And the six groups will evolve into a committee system with carefully defined functions, such as outreach to public libraries and community colleges. The choice of an executive director, Daniel Cohen, a superb historian and Internet expert from George Mason University, was announced on March 5; the first staff members have already been hired; and administrative headquarters are being set up in Boston.

Those first steps will not lead to the creation of a top-heavy bureaucracy. On the contrary, the “distributed” character of the DPLA means that its operations will be spread across the country. Its growing collection of metadata (Harvard has already made available 12 million openly accessible metadata records) will be stored in computer clouds, and its activities will be funneled through two kinds of “hubs.”

The DPLA’s “content hubs” are large repositories of digital material, usually held in physical locations like the Internet Archive in San Francisco. They will make their data accessible to users directly through the DPLA without passing through any intermediate aggregators. “Service hubs”—centers for collecting material—will aggregate data and provide various services at the state or regional level. The DPLA cannot deal directly with all the libraries, archives, and museums in the United States, because that would require its central administration to become involved in developing hundreds of thousands of interfaces and links. But development among local institutions is now being coordinated at the state level, and the DPLA will work with the states to create an integrated system for the entire country.

Forty states have digital libraries, and the DPLA’s service hubs—seven are already being developed in different parts of the country—will contribute the data those digital libraries have already collected to the national network. Among other activities, these service hubs will help local libraries and historical societies to scan, curate, and preserve local materials—Civil War mementos, high school yearbooks, family correspondence, anything that they have in their collections or that their constituents want to fetch from trunks and attics. As it develops, digital empowerment at the grassroots level will reinforce the building of an integrated collection at the national level, and the national collection will be linked with those of other countries.

The DPLA has designed its infrastructure to be interoperable with that of Europeana, a super aggregator sponsored by the European Union, which coordinates linkages among the collections of twenty-seven European countries. Within a generation, there should be a worldwide network that will bring nearly all the holdings of all libraries and museums within the range of nearly everyone on the globe. To provide a glimpse into this future, Europeana and the DPLA have produced a joint digital exhibition about immigration from Europe to the US, which will be accessible online at the time of the April 18 launch.

Of course, expansion, at the local or global level, depends on the ability of libraries and other institutions to develop their own digital databases—a long-term, uneven process that requires infusions of money and energy. As it takes place, great stockpiles of digital riches will grow up in locations scattered across the map. Many already exist, because the largest research libraries have already digitized enormous sections of their collections, and they will become content hubs in themselves.

For example, in serving as a hub, Harvard plans to make available to the DPLA by the time of its launch 243 medieval manuscripts; 5,741 rare Latin American pamphlets; 3,628 daguerreotypes, along with the first photographs of the moon and of African-born slaves; 502 chapbooks and “penny dreadfuls” about sensational crimes, a popular genre of literature in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; and 420 trial narratives from cases involving marriage and sexuality. Harvard expects to provide a great deal more in the following months, notably in fields such as music, cartography, zoology, and colonial history. Other libraries, archives, and museums will contribute still more material from their collections. The total number of items available in all formats on April 18 will be between two and three million.

How will such material be put to use? I would like to end with a final example. About 14 million students are struggling to get an education in community colleges—at least as many as those enrolled in all the country’s four-year colleges and universities. But many of them—and many more students in high schools—do not have access to a decent library. The DPLA can provide them with a spectacular digital collection, and it can tailor its offering to their needs. Many primers and reference works on subjects such as mathematics and agronomy are still valuable, even though their copyrights have expired. With expert editing, they could be adapted to introductory courses and combined in a reference library for beginners.

At one time or other, nearly every student comes in contact with a poem by Emily Dickinson, who probably qualifies as America’s favorite poet. But Dickinson’s poems are especially problematic. Only a few of them, horribly mangled, were published in her lifetime. Nearly all the manuscript copies are stored in Harvard’s Houghton Library, and they pose important puzzles, because they contain quirky punctuation, capitalization, spacing, and other touches that have profound implications for their meaning. Harvard has digitized the originals, combined them with the most important printed editions (one edited by Thomas H. Johnson in 1955 and one edited by Ralph W. Franklin in 1981), and added supplementary documentation in an Emily Dickinson Archive, which it will make available through its own website and the DPLA.

The online archive will enrich the experience of students at every level of the educational system. Teachers will be able to make selections from it and adjust them to the needs of their classes. By paying close attention to different versions of a poem, the students will begin to appreciate the way poetry works. They will sharpen their sensitivity to language in general, and the lessons they learn will help them gain possession of their cultural heritage. It may be a small step, but it will be a pragmatic advance into the world of knowledge, which Jefferson, in a utopian vein, described as “the common property of mankind.”

This Issue

April 25, 2013

Scientology: The Story

Vichy Lives!—In a Way

-

*

See Robert Darnton, “Google’s Loss: The Public’s Gain,” The New York Review, April 28, 2011. ↩