It seems a different era already, those days in 2009 and 2010 when Barack Obama and his large Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress were passing major pieces of legislation. And it was a different era—as we have seen since the Republicans took control of the House of Representatives after the 2010 elections. Since then, legislation of any significance has been nearly impossible to come by.

The official record shows the passage of 283 laws by the 112th Congress, which sat from January 2011 to January 2013. It sounds like an impressive number, but in fact most of these were technical or quite narrow in scope. At most there were fewer than ten truly important pieces of legislation, and arguably fewer than five. Virtually all had to do with the ongoing fiscal trench warfare, simultaneously grueling and tedious, that engulfed the capital during the 112th Congress and has continued into the current 113th. The bills were passed through clenched teeth on both sides.

Beltway insiders, the people from think tanks and nonprofit groups and such who have devoted their careers to seeking legislative outcomes, must persuade themselves that the legislative process can still work. Moments of vindication and triumph—a fiscal “grand bargain” between the two parties, bipartisan immigration reform, new gun control laws—must be within their grasp. Otherwise what are they doing with themselves all day, and why? The Beltway culture requires that these people make, at meetings and seminars, frequent professions of optimism as the audience members nod their heads hopefully, even as everyone knows these professions to be false.

The fact is that Capitol Hill barely functions. Its secondary purposes are still met with efficiency: staffers help constituents with their Medicaid questions; members secure funding for new senior centers; letters of congratulations are mailed out to centenarians; the artwork of promising high schoolers continues to be mounted in the long, curving subterranean hallway from the Longworth House Office Building to the Capitol. But there is hardly any legislation.

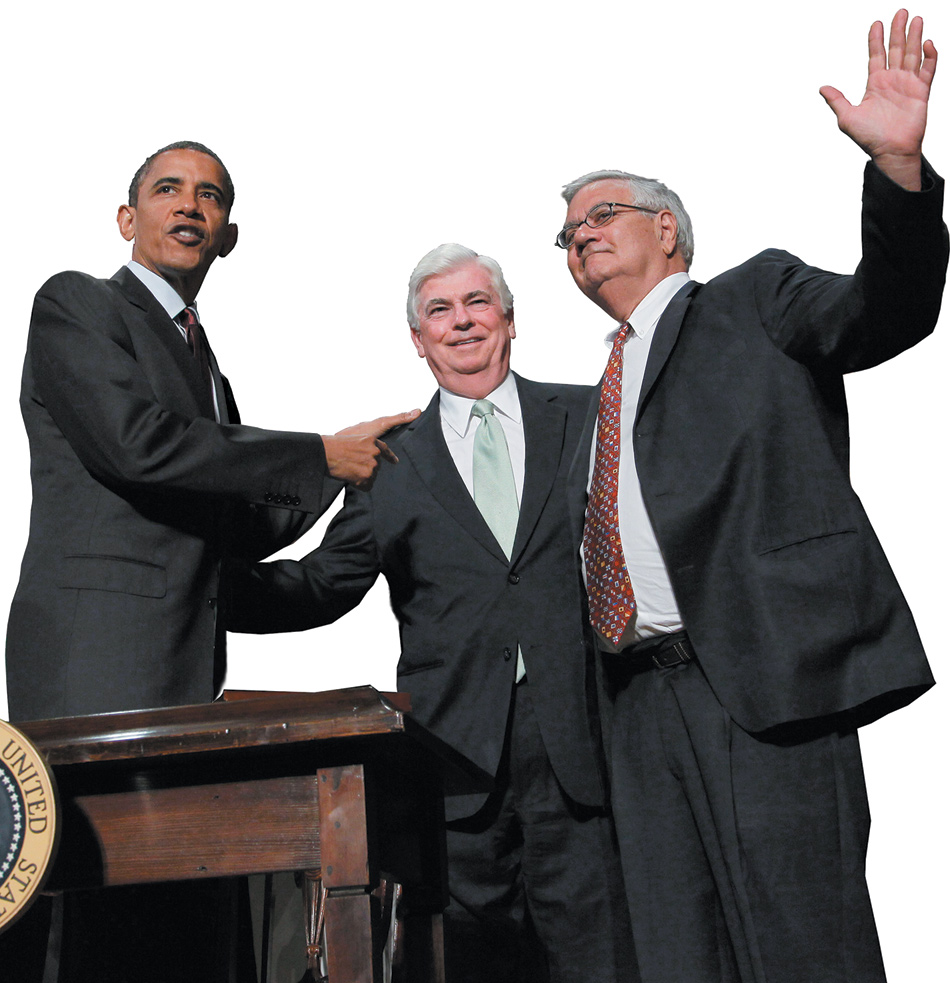

One is tempted (especially if one is a Democrat) to think back on 2009 and 2010 as a comparative golden era. And comparatively, it was. There was credit card reform, student loan reform, and equal pay for women, to start with the smaller but still quite meaningful items. Then, of course, there was health care, the new approach to the stimulus, the rescue of the auto companies, and financial reform. But the great value of Robert G. Kaiser’s Act of Congress, which chronicles the financial reform bill from inception to passage, is its refusal to accept the Washington cliché and argue that the Dodd-Frank legislation represents a moment when Congress worked the way it is supposed to.

To the contrary, the book paints a harrowing picture of dysfunction. It shows that Dodd-Frank became law only after an endless slog and several near-fatal scares. Thus a paradox makes Act of Congress particularly valuable and worth reading. It uses the passage of the most far-reaching piece of financial reform legislation since the New Deal to show not how Congress works, but how it doesn’t, even when a result is attained.

Think back to September 2008, when the country and world were on the verge of global economic meltdown. Kaiser, a longtime Washington Post veteran whose experience in covering the capital goes back to the 1970s, evokes the moment well, opening his book with a tense meeting in then Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office arranged for September 18 of that year by George Bush’s Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, a meeting that Paulson insisted to the Speaker “cannot wait until tomorrow morning.” Paulson and Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke told the assembled senators and House members from both parties that disaster such as they’d never seen loomed before them. Bernanke said that “if we don’t act in a very huge way, you can expect another Great Depression, and this is going to be worse.” Paulson said, “I’ve never seen anything like this.” Senator Chuck Schumer, who was present, later told Kaiser: “I could hear everyone gulp.” Congress acted quickly to bail out the banks.

But the next and more difficult challenge would be passing reform legislation designed to ensure that a crisis like that one—driven by large banks and other large-scale holders betting against their own loans—could not happen again.

I remember wondering, in the spring and into the summer of 2009, just what this reform legislation would contain and why it was taking so long. It wasn’t that the principals weren’t working on it. Barney Frank, who chaired the House Financial Services Committee and through whose eyes much of Kaiser’s story is told, had his first conversations with the new Obama administration about financial regulatory reform on February 2, 2009, not two weeks after Obama took office. Frank originally thought that he would be able to pass sweeping legislation in the House by April or May.

Advertisement

Chris Dodd, who chaired the counterpart Senate committee and who is Kaiser’s other principal source for Act of Congress, knew that the Senate would need more time, as the Senate inevitably does. But in that Beltway-culture way, hopes were high. Dodd hosted a dinner of the Democratic members of the Senate Banking Committee at a Capitol Hill steak house, informing them, in Kaiser’s words, that he was eager “to follow Banking Committee tradition and produce a bipartisan bill on regulatory modernization.” Frank, after an early White House meeting that included Richard Shelby, the top Republican on the Senate Banking Committee, said: “One of the hopeful things was Dick Shelby saying that he plans to be very supportive of this and he and Dodd appear to be ready to work together.”

Obama made it clear to Dodd and Frank that in contrast to the health care legislation, which was being written on the Hill, the president’s staff, not theirs, would take the first pass at drafting legislation. The two men accepted this, but they ended up waiting a long time—language wasn’t completed until June, and even then what was produced was not actual legislation but a white paper outlining general goals. Among them: (1) creating a new “systemic risk regulator” to crack down on risky behavior by large financial firms (of all kinds, not just banks, since a nominal insurance company, AIG, had done much to precipitate the crisis); (2) establishing a new “resolution regime” for failing banks, to close them down in an orderly way; (3) regulating the markets in derivatives; (4) requiring firms that gamble with mortgages to retain a financial interest in the mortgage-based bonds they created in order to give them an incentive to see that the underlying loans were solid.

Every so often, Kaiser flings open interesting little windows on the broader process, relaying the thoughts and actions of what are called in Washington the various “stakeholders.” Apparently some clients of the Wall Street law firm Davis, Polk, and Wardwell—Kaiser doesn’t say which clients—requested that the firm analyze this white paper for them, so the clients could plot a lobbying strategy. Davis, Polk returned the verdict that the outline was “far less revolutionary than some either feared or hoped for” and reflected “an ‘art of the possible’ approach to regulatory reform.” One might have thought, as the president surely did, that this was legislation that could have won some smattering of Republican support.

Many members of Congress are dull characters, but Kaiser is fortunate that his two principals bring considerable personality to his enterprise. Frank, who retired at the end of his last term, is well known for his acidic wit and his rumpled, beleaguered mien. “Irascible” is the euphemism usually employed by Washington journalists to describe him. The noneuphemistic way to describe him would be “unpleasant.” Indeed he’s so brusque, so uninterested in small talk to the point of appearing to be repulsed by the idea of it, that it’s hard to imagine how he became a politician, and harder still to see how he ever won elections. While he was always deeply interested in the substance of policy problems—he started his career as an aide to Boston Mayor Kevin White in the early 1970s—the electoral side of politics horrified him, and in his early races, Kaiser reports, aides worked to keep him away from voters lest he alienate them. A staff member from those days told the author: “You have to love Barney Frank to like him.”

Dodd is a less mythic figure in Washington, but nevertheless a man with an unusual history of his own. His father, Thomas Dodd, was a venerated Great Society–era Connecticut senator who ran into some ethics problems late in his career. He was censured and voted out after two terms. Chris, a bit of a bounder as a youth who rarely made dad proud, excitedly called home one day from law school at the University of Louisville to report that he’d made the law review; his father died of a heart attack that night. In the House and later in the Senate, Dodd was known as an unapologetic liberal by day—and by night, especially in the 1980s when both were divorced and single, as Ted Kennedy’s closest drinking buddy. He remarried later, and became a father for the first time at age fifty-seven in 2001.

Kaiser’s account makes it abundantly clear that this complex, extensive piece of legislation would probably never have been passed if not for these two men and their different but complementary sets of skills. Frank’s great asset was his critical intelligence, and throughout the process, he impressed everyone, ideological foes in particular, with his knowledge of the financial industry. Very few legislators truly understand high finance, and Frank was an exception (and could not be buffaloed by bankers or their lobbyists). In addition, Frank, though unconcerned with bonhomie, understood how to be a good and gracious committee chairman, making sure his unwieldy committee’s members (sixty of them in all) felt that they’d had a chance to speak their piece and have their amendments at least looked at.

Advertisement

Dodd’s asset was his cheerful relentlessness, which in turn was embedded in his increasingly anachronistic faith in the United States Senate and its ability to do great things. To announce the commencement of his committee’s work on the bill in November 2009, he had his staff reserve one of the Senate’s most historic rooms, the second-floor caucus room in the Russell Building, where both John and Bobby Kennedy had announced their presidential candidacies and where the hearings on Joe McCarthy and the US Army had been held. But it turned out not to be quite like the old days:

The room was flooded in electric light for television cameras, but the networks had not responded to Dodd’s attempt to create a historic occasion. Just C–SPAN sent cameras. The two long tables reserved for reporters had many empty seats, as did the public gallery. Only the seats for Senate staff were full, at least sixty men and women in rows behind the long table covered in wine-red felt where the senators sat.

Dodd also made the bill’s passage possible, Kaiser writes, by deciding to end his career for the sake of it. His 2008 run for the presidential nomination, and specifically his decision to move his young family to Iowa, had rankled Connecticut voters. He’d served five terms and slipped in the polls. Now that he was vulnerable, and with 2010 being a year in which Republicans thought they might regain control of the Senate, he understood that his seeking reelection would harm reform’s chances. The “pressure would be on his Republican colleagues on Banking not to help him produce a reform bill” that might improve his chances of reelection. He was not so romantic about the Senate that he couldn’t see this reality.

It took a year and a half from those early White House meetings until the day—July 21, 2010—when Obama signed the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act into law. What happened, and why did it take so long?

The main answer, unsurprisingly, is that the Republicans resisted a legislative victory for Obama. Senator Shelby and Representative Spencer Bachus, the ranking Republican on the House Financial Services Committee, were not, by the grim standards of today’s GOP, terrible partners for Dodd and Frank to have. They cared about the substance of the bill, Kaiser reports, and they were well aware that public anger at the banks required that Congress do something. But they were both from Alabama. Whatever populist anger existed there was aimed at the “moocher class” of people who took out mortgages they couldn’t afford, and Shelby and Bachus had to be careful to behave accordingly.

And so on that November morning of the Banking Committee’s sparsely attended kickoff event, Chairman Dodd was counting on some encouraging words from Shelby, who instead launched into an “eighteen-minute tirade,” as Dodd’s staff called it, charging that “this Committee has not done the necessary work to even begin discussing changes of this magnitude.” He was referring to the fact that Dodd, and Frank for that matter, had chosen not to do “Pecora”-style investigations into the lenders’ behavior.1 But it seemed likely that Shelby was just using this as his excuse—he simply needed to be seen as being against the bill. Shelby added that in his view, the bill needed “a complete rewrite and we intend to offer a substitute at the appropriate time.”

Less than two weeks later, however, Shelby was in Oxford. There he gave a serious and substantive speech to the Oxford Union, endorsing several ideas consistent with Dodd’s approach. Obviously, Shelby knew that the folks back home would have seen his “tirade” remarks, and would probably not hear a word he said in England. But Dodd, ever the optimist, tried to convince himself and his staff that the Oxford Shelby was the real Shelby.

Even if Dodd was right about that, the problem was that Shelby clearly felt he could not take on Alabama voters—or Mitch McConnell, the Republican Senate leader. If Act of Congress has a villain, it is McConnell. At a few different points, Shelby seems perhaps ready to talk with Dodd, only to back away mysteriously. Kaiser doesn’t really nail why he did so, which is a shame—in his defense, I can testify that such facts are extremely difficult to nail down—but it certainly appears that McConnell warned him at certain times that participating in the legislative process on financial reform was forbidden.

The same message was delivered to committee member Bob Corker of Tennessee, who did try for a time to work with Dodd, an episode that Kaiser returns to periodically and is painful to read. Corker and Dodd and their staffs—Kaiser names the crucial staff members and makes it clear they actually do the hardest work—talked for weeks about a bipartisan bill of the sort Dodd originally wanted. They’d made considerable progress. Dodd knew that compromises with Corker might cost him the votes of a couple of the most liberal Democrats, but that was fine with him if he could win enough Republican votes to cover for them.

But members of Shelby’s staff were communicating their displeasure to Corker’s staff about their boss’s willingness to collaborate. And in March 2010, a second Republican, Judd Gregg of New Hampshire, backed out of a crucial meeting. At that point, Dodd knew that Corker could bring no other Republicans along with him. When Dodd knew that, he knew that he would need all fifty-nine Democrats to back his bill. So he went back to a partisan bill. The talks collapsed.

After the bill was passed, McConnell made a remark to The Atlantic, which Kaiser reprints:

We worked very hard to keep our fingerprints off of these [Democratic] proposals, because we thought—correctly, I think—that the only way the American people would know that a great debate was going on was if the measures were not bipartisan. When you hang the “bipartisan” tag on something, the perception is that differences have been worked out, and there’s a broad agreement that that’s the way forward.

Forget the people who lost their homes; forget the billions or trillions of dollars that had vaporized; and forget legislating. The only thing that mattered was “a great debate,” i.e., partisan advantage, political polarization. The substance apparently meant nothing to him.

Interestingly, Kaiser—whose last book about Congress was titled Too Damn Much Money—doesn’t dwell very much on the mighty lobbying organizations that tried to influence the bill. We meet Edward Yingling, the head of the American Bankers’ Association, and Camden Fine, who leads the Independent Community Bankers of America, the umbrella group representing the small banks. But they are largely, and oddly, passive figures here.

Some of the anecdotes reveal how deals are put together at this level. Frank at one point approached Fine to try to persuade him not to oppose the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau that the law created. Fine represented institutions that did not cause the meltdown. He didn’t want to suffer for the big banks’ errors, and was suspicious of the new bureau. But after some back and forth, the two men agreed it would not have jurisdiction over banks with assets less than $10 billion. Fine told Frank: “I’m okay with that standard.” In fact, of his 5,300 member institutions, only four had assets greater than $10 billion. Fine and his group did not criticize the new agency.

Lobbying was intense, particularly on the issue of control of derivatives, yet Kaiser reports no episode in which a powerful lobby managed to pervert or distort the legislation. But it went through plenty of bizarre permutations nonetheless. Toward the end, with the Republicans mostly out of the picture, some Democratic senators caused Dodd anguish, namely Maria Cantwell of Washington, Russ Feingold of Wisconsin, and Blanche Lincoln of Arkansas.

Lincoln chaired the Agriculture Committee and thus had jurisdiction over matters relating to commodities, and she pushed hard for new regulations of derivatives, about which Dodd was skeptical. She was facing a primary challenge from her left (she defeated that opponent but lost to a Republican in the general election). Feingold insisted on full restoration of the New Deal–era Glass-Steagall Act that separated commercial banking from investment banking. Both took principled positions. But both voted “no” on the cloture votes that were critical in avoiding a Republican filibuster. At the eleventh hour their votes against cloture nearly wrecked a year and a half of painstaking work by their colleagues.

If Dodd’s bill had not had the backing of three Republicans—Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins of Maine, and Charles Grassley of Iowa—it would have died. Scott Brown of Massachusetts delivered one final scare. He had personally promised Harry Reid that he would support the bill but reversed himself, under apparent pressure from McConnell and Massachusetts-based financial firms. The next day, after assurances from Frank and John Kerry, he reversed himself again and voted to end debate and send the bill to final passage. It finally became law with exactly six Republicans—three in the Senate, three in the House—voting for it.

What kind of bill is it? Kaiser is noncommittal. And in fact, his book went to press before the story was over. A large bill like Dodd-Frank often uses general language and leaves it to bureaucrats to fill in the specifics later. This rule-writing process, as it’s called in Washington, is happening right now, and depressingly, it gives the financial industry groups and their lobbyists a second chance to distort legislation. They lobby on this part of the process no less furiously than when a bill is moving through Congress—with, of course, far fewer journalists and others paying attention.

It’s not all bad. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission is almost done with finalizing the basic structure of derivatives reform, and according to Lisa Donner of the group Americans for Financial Reform, the big five banks that control almost all of the derivatives business “are losing out.” Right now the banks and the reformers are fighting over the “extraterritorial extension” rule, which would cover derivatives deals executed by the banks’ overseas subsidiaries.

But in general, the process is moving painfully slowly and the financial interests are succeeding in watering down the law’s measures on bank capitalization, as well as the “Volcker Rule” that would proscribe proprietary trading (trading with a bank’s own money purely for the sake of profit), and the bill’s Section 716, which would require banks to push their derivative business out to separate subsidiaries. Industry groups have not just petitioned bureaucrats to write favorable rules—they have even sued to get their preferred language, and in some cases have gotten their way. Haley Sweetland Edwards tells this story and many other chilling ones in her recent piece “He Who Makes the Rules,” in The Washington Monthly, the best article on how Washington works I’ve read in years. She writes:

In the last quarter of 2010, just a few months after Dodd-Frank passed, the financial industry raked in nearly $58 billion in profits alone—about 30 percent of all US profits that quarter. With that sort of bottom line, spending a hundred million or so to kill a single rule that could “cost” them a couple billion in profits is a pretty good return on investment.

Yet by Washington standards, Dodd-Frank is a success story. Looking at today’s Congress, we see very few prospects for more such outcomes. The chances of a “grand bargain” on the budget and tax legislation seem distant today, and the government may go bumping along with one short-term financing bill after another. Perhaps that’s a good thing, since Obama would have to give up a great deal on entitlements such as Medicare before Republicans even considered a longer-term deal. Gun control legislation might have a slim chance, but in mid-March, a Senate committee could pass background checks—supported by 90 percent of Americans in polls—only along strict party lines. And the assault weapons ban provision was killed by Senate Democrats.

Immigration is the one subject on which those hopeful Beltway heads still nod around the Brookings seminar table. Every few days, someone reports that a deal in principle in either the House or the Senate is imminent. But the Obama administration has still introduced no legislation on the subject, and I remain a skeptic, especially with regard to the House. There is very little incentive for most Republican House members, who represent districts where the only real political pressure they feel is from their right, to endorse a path to citizenship for undocumented aliens. Speaker John Boehner might allow a vote, and could pass a bill if all Democrats and a small number of Republicans were for it. But he would be putting his speakership at risk by doing so.

This severely limits Obama’s options for a second term. But it suggests that he will have to run in essence what my Daily Beast colleague, the political consultant Bob Shrum, not long ago called a campaign for a “third term”—that is, a campaign to try to win back the House (and hold the Senate) in the 2014 midterms.2 If he has Democratic majorities in both houses, he may be able to pass one or two more major bills. If he does not, the domestic Obama agenda may well be finished.

—March 28, 2013

-

1

The Pecora Commission had been empaneled by the Senate Banking Committee in 1932 to investigate the causes of the 1929 crash. Ferdinand Pecora took over as chief counsel in 1933 and got much public attention, forcing high-profile resignations. Dodd and Frank both felt that such a probe, while satisfying a public thirst for vengeance, would get in the way of reform legislation. ↩

-

2

See Robert Shrum, “Obama Must Fight One More Campaign: To Keep Senate & Win House in 2014,” The Daily Beast, February 8, 2013. ↩