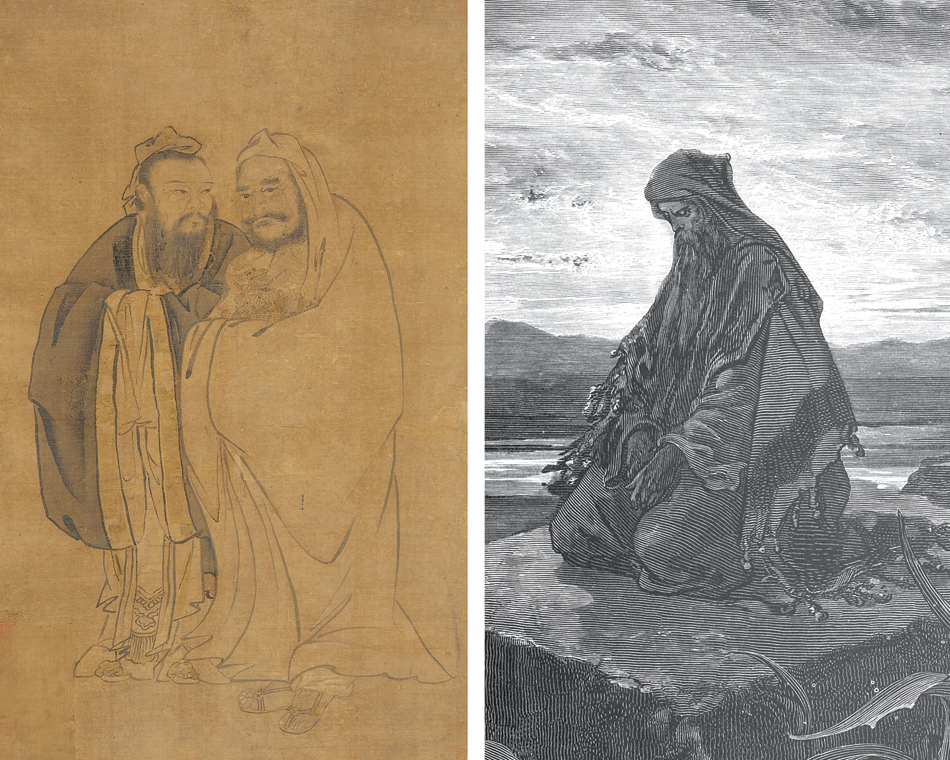

Reflecting on human history over the previous millennia, a few European thinkers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries noticed a surprising conjunction. Many of the world’s most influential figures—Confucius, Buddha, the prophets of Israel (Amos, Isaiah, Jeremiah), Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Zoroaster all emerged in their respective nations—China, India, Judaea, Greece, and Iran—in the middle of the first millennium BC, roughly between 800 and 200 BC. Although more recent scholarship has tended to move Zoroaster out of this chronological frame back into an earlier one, the coincidence remains impressive. The French Iranist Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron in the late eighteenth century may have been the first to draw attention to it, and a German philosopher, Ernst von Lasaulx, subsequently expanded on it in a dense but little-known work of 1856 under the bizarre title A New Attempt at an Old Philosophy of History Based on the Truth of Facts. While stressing empirical analysis, von Lasaulx conspicuously privileged religion and argued for organic growth and decay in world history.

In Europe at this time the great turning point in the history of mankind was generally agreed to be the earthly appearance of Jesus Christ, who quite clearly did not arrive simultaneously with the magisterial figures of the mid-first millennium BC. Hegel went so far as to assert that the idea of the trinity of God was the pivot on which the history of the whole world turns—both its starting point and its goal. The centrality of Christ in history, or at least Western history, impelled the classical historian Johann Gustav Droysen to compose a very long narrative, beginning with Alexander the Great, that would trace Greek and Near Eastern events that led inexorably, as he believed, to Christianity. His work on what he called Hellenismus, which today we often call Hellenistic culture, gave a new momentum to studies of early Christianity, but he was oblivious of the intriguing coincidence of Confucius, Socrates, Buddha, and their expositors.

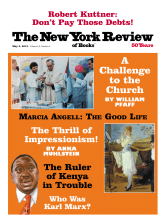

Meanwhile, in a world conceptually if not physically apart, Muslims had long before inaugurated their own historical time with the migration (hijra) of Muhammad to Medina in 622, and that date remains to this day the great turning point for Islamic historiography. None of the historians in China, India, or Iran seems ever to have noticed that the careers of their ancient leaders and thinkers occurred in the days of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, or the Hebrew prophets. Drawing attention to this chronological oddity was an entirely Western enterprise that may have gained a certain traction from German Romanticism by invoking exotic peoples and places. But even in the West it had limited currency because the beginning of Christianity remained the immovable turning point in human history.

All this changed after World War II, when a German philosopher, Karl Jaspers, published in 1949 his book Vom Ursprung und Ziel der Geschichte (On the Origin and Goal of History) and invented the Achsenzeit (Axial Age) as a designation for the period from 800 to 200 BC. This is the text that underlies all the collected essays in The Axial Age and Its Consequences, the thick volume edited by Robert Bellah and Hans Joas. In 1949 Jaspers looked back nostalgically to a pre-Christian epoch in world history. He readily seized upon the contemporaneity of Confucius, Buddha, the Jewish prophets, Socrates and his disciples, and, in his view, Zoroaster too, to argue that this era was a pivotal moment in world history, an Axial Age. He claimed to have found inspiration in Hegel, although Hegel himself would certainly not have imagined a turning point that would replace the Christian one.

In matters of substance, Jaspers, as he acknowledged in his book, made use of the long neglected work of Ernst von Lasaulx as well as the 1870 commentary of Victor von Strauss on Laozi, the founder of Daoism. Whatever its antecedents, the theory that Jaspers launched with great subtlety and brilliance was very much his own. He explicitly compared what he was doing with the work of Oswald Spengler and Arnold Toynbee, who identified numerous historical epochs that all had a beginning and an end, eight for Spengler and twenty-one for Toynbee. Jaspers opted for a comprehensive “before and after” approach that would single out a time when human history changed. In the forefront of the change, as he saw it, were philosophers: “Zum erstenmal gab es Philosophen’’ (For the first time there were philosophers). This was presumably not unrelated to the fact that Jaspers himself was a philosopher.

The Bellah-Joas collection of papers on the Axial Age and its consequences is the latest and perhaps most substantial contribution to the discussion that Jaspers started over sixty years ago. Most of the contributions to this volume derive from papers that their authors presented at a conference held at the University of Erfurt in 2008, where, to stimulate discussion, Bellah had provided drafts of the last four chapters of his forthcoming book, Religion in Human Evolution, which was eventually published in 2011. The conclusion of the present volume reproduces material from the final chapter of that book.

Advertisement

The Erfurt conference on the Axial Age was but one of a long series of conferences on this subject over the last three decades. Jaspers’s idea of an Axial Age has been taken up in earnest by sociologists, such as the two editors, but much less by philosophers. The charismatic impresario of most of the conferences, as well as a major participant and arguably the most prolific expositor of Jaspers’s thought, was the late Israeli sociologist Shmuel Eisenstadt, who devoted himself unremittingly to promoting Jaspers’s hypothesis as an instrument for analyzing global history. As a veteran of two of Eisenstadt’s conferences on the Axial Age, I can confirm that Jaspers’s ideas could bring together historians of antiquity and sociologists in debates that were always exciting and occasionally even fruitful.

As Joas rightly stresses in his introductory chapter, the fundamental characteristic of the Axial Age was the emergence of a transcendental vision in the work of its principal thinkers. Some were prophets, but most were philosophers who were to a greater or lesser extent concerned with divine power and presence. Their vision had an impact on what went on in the real world, or “the mundane sphere” in axial jargon. Earthly politics and morality had to be evaluated and, when necessary, altered by reference to the transcendental vision that the pioneering thinkers had introduced. This is what Eisenstadt called the institutionalization of a transcendental vision.

The Italian historian Arnaldo Momigliano, whom Eisenstadt involved in several of his discussions, saw this institutionalized transcendentalism as having acted as a catalyst for the analysis and criticism of existing social customs and systems. In Jaspers’s terms, human society itself became an object of reflective analysis, and for him in 1949 there was no sign of this before 800 BC. A transformation of this kind was imagined to have affected morality, politics, and religion. The religious component of transcendental doctrines inevitably dictated innovations and transformations in both theology and ritual. Confucianism, Buddhism, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism all exhibit the impact of the supposedly axial pioneers.

Obviously this is heady stuff, with a rich potential for high-minded silliness, but it has proven to be a useful way of thinking about the development of ethics, political thought, and religion, particularly among sociologists. Historians, like Momigliano, have occasionally joined the discussion but not led it, and philosophers, with the distinguished exception of Charles Taylor, who is represented in the Bellah-Joas volume, have been conspicuous by their absence. It is wholly understandable that in writing his big book on religion in human evolution, Bellah, an eminent sociologist, would have had recourse to Jaspers’s ideas. But by his own admission he makes use of a neo-Darwinian notion of evolution in the human past, even though this notion does not fit at all comfortably with Jaspers’s postulate of a great turning point or axis. Jaspers’s attribution of this idea to Hegel appears to be a faulty recollection of Hegel’s word “pivot” (Angel)—rather than “axis” (Achse)—to designate a turning point between two entirely different periods of the human past. But for Hegel these periods were, as Jaspers knew perfectly well, pre-Christian and Christian. The idea of a decisive turning point is hardly evocative of Darwinian evolution, and the complete title of Bellah’s book illustrates this incompatibility: Religion in Human Evolution: From the Palaeolithic to the Axial Age. Jaspers’s hypothesis undoubtedly has implications for what happened after the Axial Age—critical reflection, action on the basis of preordained moral or religious concepts—but it is not easy to incorporate it into any evolutionary interpretation of either the pre- or post-axial periods. Bellah ends his book with four chapters on the axial developments in China, India, Greece, and ancient Israel, but he does not carry his evolutionary theory beyond that.

The word that Eisenstadt liked to use for historical developments that lay outside, and usually after, the Axial Age was “breakthrough,” which took over the German expression Durchbruch. The Axial Age itself was imagined as the greatest of all breakthroughs, although it has never been clear exactly what was being broken through. For Christ and Muhammad as momentous historical dividers after the supposed Axial Age, Eisenstadt and others could invoke the notion of a “secondary breakthrough.” The same could presumably be said of the age of Galileo and Kepler, and the editors of the volume under review even ask portentously, “Is it possible that we have entered a new Axial Age?” But it is not obvious how we would be able to tell, and what difference it would make if we could. What is much more pertinent is whether the Axial Age itself can survive as anything more than a stimulus for historical or sociological discussion.

Advertisement

The best of the essays in the Bellah-Joas volume comes from Jan Assmann, another veteran of Axial Age conferences over many years. He has a rare clarity in addressing murky issues. This may have something to do with his experience, as an Egyptologist, in expounding pharaonic theology. The greatest achievements of ancient Egypt, above all the monotheism of Akhenaton, all occurred outside the charmed frame of Jaspers’s Axial Age. Assmann is well aware of this. He says explicitly that he cannot believe in the Axial Age as “a global turn in universal history” in the middle of the first millennium BC, but he nevertheless finds the concept of axiality “a valuable and even indispensable analytic tool in the comparative study of cultures.” He is right on the mark when he writes: “Jaspers’ opposition between the Axial and the pre-Axial worlds appears to me in many respects as a secularized version of the Christian opposition of true religion and paganism or historia sacra and historia profana.” For Assmann, Akhenaton, Moses, and Zoroaster (whom he dates to the second millennium BC, not the first) are axial figures, no less than Jesus and Muhammad in the first millennium AD. Assmann argues that what makes these individuals “axial” is not when they lived but when their work became canonical, and that depends on the rise of literacy and the written record.

Eisenstadt would have dealt with all these post-axial complications by invoking secondary, or even tertiary, breakthroughs, and Assmann shows that he is aware of this when he complains that breakthroughs in different civilizations and under different conditions have led to “an unnecessary mystification of the historical evidence.” It is undoubtedly true that the importation of transcendent visions into the management of worldly (“mundane”) affairs, as represented, for example, by Constantine the Great after his conversion to Christianity, caused major changes in world history, but trying to distill this process into an axial theory can produce something far worse than mystification.

The essay by Ingolf Dalferth is a case in point. It was not written for the Erfurt conference and would certainly have been incomprehensible if it had been presented there. In print it is a ludicrous parody of philosophical prose. Here is a sample:

By distinguishing itself from itself the Transcendent becomes the Unconditioned that, without ceasing to be the Transcendent, constitutes the difference between Immanence and Absolute Transcendence not merely by distinguishing itself from Immanence (Immanence/Absolute Transcendence) but rather by breaking into the Immanent in such a way that its reentry makes it impossible not to distinguish between immanence and transcendence within Immanence (immanent immanence/ transcending immanence).

The ineradicable flaw in Jaspers’s theory of an Axial Age is the same as the flaw in the nineteenth-century European view of Christ’s advent as the greatest turning point in world history. Although taking full account of China, India, and Judaea, it envisions global history exclusively from the perspective of Western experience and perceptions. This is the way the history of the world looked or looks even now to many Europeans, or, for that matter, non-Europeans like Eisenstadt himself, educated in the European tradition. The only difference is that Jaspers has removed Christ from center stage and put Confucius, Buddha, Isaiah, and Plato there instead. Christ’s centrality was largely owing to Christian historians and philosophers in the West.

It was a generous instinct on the part of a European such as Jaspers to replace him with spiritual leaders in China, India, and Greece, to say nothing of the biblical prophets, but only as they were understood in Western Europe in the twentieth century. Reverence for all of these figures among their own followers in their own societies has been no less sectarian, regional, and parochial than the reverence of Christians for Christ. Although what Jaspers proposed was, if not altogether new, very different, in the end it was as Eurocentric as the doctrine he wanted to subvert. In addition, it elevated synchronicity, which Jaspers explicitly defended in his analysis, into a historical tool of questionable legitimacy.

Historians simply cannot resist chronological units. These units, which rarely have any intrinsic coherence of their own, undoubtedly help us in thinking about the chaotic and unceasing flow of historical events, personalities, ideas, and movements. We speak confidently about decades (the Thirties or the Sixties) or of centuries (the eighteenth century, or even the long eighteenth century) as if such entirely artificial constructs conferred some kind of meaning on what happened in those time frames. Sometimes simultaneity or contemporaneity are actually meaningful, but often they are no more than coincidence. Jaspers’s insight into the spiritual developments of the mid-first millennium BC across a considerable geographical space should not blind us to the fact that, so far as we know, nothing comparable was going on in that allegedly transformative period in Russia, Scandinavia, Africa, North and South America, or, in fact, Europe itself to the west of Greece.

Yet archaeology has revealed important cultural and social changes that might reasonably expand the debate about the Axial Age. Jaspers, like von Lasaulx, wrote as a philosopher, but in promoting his “pivotal” age he was trying to rewrite history itself and not merely think about it. Eisenstadt, Bellah, and others have responded to his challenge by deploying the conceptual methods of sociology, but they have not enriched their analysis with the abundant evidence that archaeology has provided, particularly in the decades after Jaspers wrote. They concentrate largely on the written record, which is, as Assmann stresses, inevitably later than the time it evokes. The construction of history from archaeological evidence has proceeded vigorously since Jaspers’s day, and conspicuously in areas he ignored, such as Mesopotamia, Mesoamerica, Russia, and Western Europe.

If the Axial Age is not to be simply a replay of history with special reference to its greatest men (Jaspers’s heroes were all men), we need to look not only at other regions than the four with which Bellah concluded his book on religion in human evolution—China, India, Greece, and ancient Israel, or even a fifth (Iran) on the old dating for Zoroaster. We need also to look at the material evidence both inside and outside those regions.

Peter S. Wells offers a useful worm’s-eye perspective in his new book, How Ancient Europeans Saw the World, in which he concentrates on cultural change as revealed in humble objects, such as pots, swords, and coins, found in graves.1 K.C. Chang and his school have fostered Chinese archaeology in the West, but it has also been energetically cultivated in China itself. Mesopotamian archaeology has major implications for the axial millennium, and the Mesoamerican civilizations of Teotihuacán and the Maya raise serious questions about the axial hypothesis. It is hard to find traces of these ancient civilizations in most of the writing that has been devoted to Jaspers. Although Jaspers himself was totally innocent of archaeology, his book’s crude diagram of the global world of mankind does find a marginal place for Peru, Mexico, and black Africa, which are all embarrassingly relegated to the category of Naturvölker (nature peoples).

The great age of ancient Mesopotamia falls largely, though not completely, before the axial frame, but its achievements in political organization, literacy, statecraft, and literature were considerable and included the epic of Gilgamesh, which would be a worthy companion to the works that Jaspers cites. Our knowledge of its civilization has been vastly enlarged by the discovery of the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–627 BC), which itself dates from the Axial Age but preserves precious texts from a far earlier time. When it comes to pre-axial Egypt, Assmann is clearly aware of the archaeological and monumental testimony for this period, but he too is more interested in concepts and texts than in the history that can be built up from the ground.

Unlike Mesopotamia and Egypt, the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica reached their peak many centuries after the Axial Age, and it would be hard to claim from the archaeological evidence that they constitute any kind of “breakthrough” or institutionalization of a transcendental vision. Yet their monuments and their religions flourished well into the period that we now call Late Antiquity, and both the Maya and Teotihuacán came to an end in circumstances that are still unclear, although the latter succumbed to a devastating fire. The sociologists who follow Jaspers have tended not to talk about this, partly because of his neglect of archaeology. But there was a revealing intervention from Shmuel Eisenstadt at a colloquium in Santa Fe in 1982. This meeting was devoted to a wide-ranging discussion of the collapse of ancient states and civilizations, and it included several of the most authoritative archaeologists working in Mesopotamia and Mesoamerica.

Eisenstadt posed the question of irreversible collapse as opposed to collapse with a possibility of regeneration or renewal. He claimed, with good reason, that both the Roman Empire and the Han Empire carried within themselves the seeds of regeneration when they came to an end, and therefore that they did not suffer total extinction. Inasmuch as these were both civilizations that came after the Axial Age, this meant for Eisenstadt that they had somehow acquired the ability to reflect on themselves by reference to lofty shared visions, and thereby to reshape themselves and establish a continuity with their former existence. By contrast, according to Eisenstadt, pre-axial civilizations were unable to do this:

In the great civilizations of the Axial Age (especially the Greek, Roman, Jewish, Christian, Chinese, Hindu, and Buddhist ones), however, collapse contains within it the seeds of likely reconstructions.2

But unfortunately, Eisenstadt explicitly linked Mesopotamia, the Maya, and Teotihuacán as older, ancient civilizations and therefore pre-axial. This serious mistake undermined not only his analysis but the whole interpretation of collapse in Jaspers’s terms. Mesopotamia was undoubtedly, for the most part, pre-axial, but the Maya and Teotihuacán cultures were clearly not and cannot be described, in Eisenstadt’s words, as “older” ancient civilizations. If archaeology had been brought into the discussion of the Axial Age, as it was into the Santa Fe discussions of collapse, the treatment of the Axial Age in the Bellah-Joas volume of essays from Erfurt might have looked very different.

The Axial Age ultimately represents a desperate attempt by a German philosopher after World War II to break the tyranny of the nineteenth-century European partition of human history into pre- and post-Christian epochs. Jaspers wanted commendably to look outside the European world he knew into a much larger world that encompassed China, India, and the Middle East. Yet he had no interest in looking anywhere else on the globe, even though he believed he was adopting a global perspective. While rejecting the old Eurocentric view, he clung resolutely to the idea of great civilizations. He rejected what he saw as a nineteenth-century positivism that gave equal importance to any people in any place and mockingly summarized this view when he wrote:

History is where people live. World history spans the globe in time and space. It is organized geographically in space. It took place everywhere on earth. The struggles of blacks in the Sudan are on the same historical level as Marathon and Salamis.

Jaspers’s mockery of such a perspective is ironic in view of the development of cultural anthropology in the second half of the twentieth century. The perspective that he found uncongenial soon acquired currency among anthropologists who, on the basis of their field work, examined patterns of human behavior in the most obscure and neglected cultures. Clifford Geertz’s analysis of the Balinese cockfight is perhaps the most famous example of this kind of thing. The title of his book After the Fact points to his interest in moving beyond historical descriptions based on texts and facts, which was so fundamental to Jaspers and his philosophy. Since cultural relativism was not to Jaspers’s taste, it took courage for a sociologist like Bellah, who is heavily indebted to the axial hypothesis, to examine less famous or resplendent cultures in his quest for an evolutionary explanation of religion. Half of his recent book on religion in human evolution is devoted to the palaeolithic period.

In searching for an alternative to the division of world history into pre-Christian and Christian time, Jaspers created a much broader worldview, but stimulating as it is, it is not in itself a breakthrough. His influential book emerged in the twilight zone between philosophy and history, and it remains there still. It has attracted lively and enduring interest from sociologists, but at the same time little attention, with some notable exceptions, from philosophers and historians. This mixed reception may be seen both as proof of its fecundity and as skepticism about its argument.

-

1

Peter S. Wells, How Ancient Europeans Saw the World: Vision, Patterns, and the Shaping of the Mind in Prehistoric Times (Princeton University Press, 2012). ↩

-

2

The Collapse of Ancient States and Civilizations, edited by Norman Yoffee and George L. Cowgill (University of Arizona Press, 1988), pp. 242–243. ↩