“For a child in love with maps and engravings,” Baudelaire wrote in “Le Voyage,” “the universe is equal to his vast appetite./Ah, how the world is great by lamplight!/Through the eyes of memory the world is small.”*

That is not how it has usually been in the work of André Aciman. His lost childhood, lovingly and subtly evoked in his memoir Out of Egypt (1994), far from diminishing over time, only grew richer in color and texture and more desirable. Aciman’s large family, Jews of Turkish and Italian origin established since 1905 in Alexandria, had prospered in their Egypt, their eccentric members leading lives of charmed privilege. As described by Aciman, their world invites comparison with that of Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet.

Home, wealth, and privileges were swept away by the paroxysms of virulent anti-Semitism unleashed by the Nasser revolution and the military intervention by the United Kingdom, France, and Israel that followed in 1956 after the nationalization of the Suez Canal. Like almost all Egyptian Jews, the Acimans went into exile, expelled or strongly nudged to leave, some members of the family taking refuge in Italy, others in France. Aciman and his parents were among the last to depart. They left in 1965, initially for Rome, their sojourn there intertwined with visits to Paris where the father found employment. At the beginning of the 1970s, they settled in New York City. Aciman graduated from Lehman College and went on to obtain a Ph.D. at Harvard University. He is now a distinguished professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, teaching among others courses on the literature of memory and exile and on Marcel Proust.

Aciman has been a prolific writer of essays, continuing to chart in them, as in the collection False Papers (2000), his chosen territory of nostalgia and loss. In addition to Harvard Square, his new novel, he has written two others: Call Me by Your Name (2007) and Eight White Nights (2010). The first begins as a sort of reconstitution of the lost easeful world of Alexandria. Readers of Aciman’s essays—for example, “In Search of Blue,” “Square Lamartine,” or “Pensione Eolo”—know how wrenching it was for the teenager to find that his parents and he had fallen on hard times, and how much he missed the Mediterranean douceur de vivre: the days spent at a beach easily reached from the terrace of the parental house, the salt flavor to be showered off one’s skin after a swim in the sea, the spicy foods, the well-trained and discreet servants, a society in which money was not mentioned in quotidian discourse for the simple reason that it was quietly and abundantly available.

Call Me by Your Name is a return to that world, transposed and reimagined. We are in a luxurious seaside villa, complete with family retainers, in an unnamed Italian seaside town, belonging to a rich Jewish professor of indeterminate nationality who invites American graduate students for prolonged stays in the summer. The narrator is Elio, the professor’s son. Like everyone in this novel except perhaps the servants, Elio is preternaturally learned; for the moment, he is busy transcribing for the guitar Haydn’s Seven Last Words of Christ. At the drop of a pin, he quotes from the Divina Commedia and plays Bach, with or without Liszt’s or Busoni’s gloss.

That particular summer’s visiting graduate student is Oliver, seven years older than Elio. With speed that may seem surprising, this being Elio’s first experience of homosexual love, he and Oliver embark on an affair, the carnal aspects of which are described with some precision, that they carry on at the family home and during a short trip to Rome. The pair are discreet but the father isn’t fooled, and toward the end of the novel, after Oliver has gone back to the US, he gives Elio advice of the “gather ye rosebuds while ye may” variety that in the circumstances seems both startlingly broadminded and banal. You had a beautiful friendship, he tells the son, remember that hearts and bodies are given to us only once.

The setting of Aciman’s second novel, Eight White Nights, is very different. It’s Christmas, and we are on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, among rich German Jews. Instead of the sudden and shared incandescent sexual passion of two young men, we have anomie. Otherwise, one is tempted to say, it’s pretty much the same deal: two ultra-cultivated characters engage in conversations peppered with graduate student puns and other linguistic inventions, disquisitions on musical form, and literary allusions caught on the fly; when the chatter stops, its place is taken by the narrator’s circular exegeses of what has been said and held back. An Eric Rohmer retrospective is in progress at a cinema on upper Broadway. The nameless twenty-eight-year-old narrator and the object of his stunted desire, twenty-two-year-old Clara, are in faithful attendance.

Advertisement

Their eight nights—white because of the snow, because of the exhaustingly late hours the couple keeps, and probably because of the Dostoevsky novella “White Nights,” the title of which the narrator conveniently drops—begin on Christmas Eve, when they meet at an opulent party given by Clara’s friends; it would seem that New Year’s Eve, the eighth night, will find them in the same apartment at a party given by the same couple. Will the narrator and Clara end up in bed? One thinks that he would like that, and that she would as well, but on the fifth night comes a bigger than usual bump in the road: invited by Clara to come up to her apartment, after a long evening of cinema, dinner, and many single-malt scotches, he tells her it’s “too soon, too sudden, too fast.” He doesn’t want to “mess this up.”

Curiously, after all the talk and the narrator’s efforts to analyze Clara, we know very little about either of them. She has a rich and beautifully trained voice, she has written a master’s thesis on a subject related to music, she is an orphan with lovely skin who wears daringly unbuttoned shirts, she drives a little silver BMW, she brings “nips” of Oban whiskey to the movies, and, like the narrator, she is unemployed. There is a studio in the narrator’s apartment and his cleaning lady has been told not to touch his papers. Perhaps he is a writer, but for the moment his occupations consist of having breakfast at a Greek diner, talking to Clara, and mulling over what they’ve said to each other and its likely consequences. Money is no problem for the narrator: when Clara and he picnic on the Oriental rug in his apartment she makes avocado, ham, and cheese panini for him, “but there was caviar too”; she insists on spreading it on the sour cream herself.

Marcel Proust being Aciman’s literary hero and avowed master, one may be forgiven for thinking of Call Me by Your Name, an elegy for a way of life reminiscent of Alexandria and for a real or imagined lost love, as a homage to Le temps retrouvé. But what is one to make of the self-consciously Proustian hithering and thithering of the narrator’s desires and abdications, synesthetic impressions, and allusions in Eight White Nights? For instance, the sound of ice crunching under the snow, as the narrator trudges up the service road off Riverside Drive,

made [him] think of Capra’s Bedford Falls and Van Gogh’s Saint-Rémy, and of Leipzig and Bach choirs and how the slightest accidents sometimes open up new worlds, new buildings, new people, unveiling sudden faces we know we’ll never want to lose. Saint-Rémy, the town where Nostradamus and Van Gogh walked the same sidewalk, the seer and the madman crossing paths, centuries apart, just a nod hello.

Or such similes as

I felt hurt, exposed, embittered, embarrassed, like a crawfish whose shell has been slit with a lancet and removed but whose bared, gnarled body is being held out for everyone to see before being thrown back naked into the water to be laughed at and shamed by its peers.

Is Aciman’s second novel intended on some level to be a retelling of the love of Proust’s narrator for Albertine? If so, one of Aciman’s successes is that, like Albertine, Clara is irresistible for the romantically inclined reader. Is the detachment from material needs and preoccupations the wish fulfillment of an exile remembering the lost affluence of Alexandria, or a strangely unironic pastiche of the French fin de siècle bourgeoisie satirized by Proust?

Aciman’s third novel, Harvard Square, is almost aggressively autobiographical. The narrator has been taking his seventeen-year-old son to visit liberal arts colleges and now, it being early summer, they’re in Cambridge, at the Harvard College admissions office, waiting for an official welcoming speech to the applicants. One supposes that because the narrator would like his son to attend Harvard he has made it the last port of call. The situation is complicated, because the son would like to “split”; he is “so not into this.” Moreover, the father’s “love” for Harvard is no simple business. He had a rocky time there, as an “outsider, the young man from Alexandria, Egypt, forever baffled and eager to belong in this strange New World.”

He finds that state of mind, loving Harvard after he had left it, even though his memories of it are not idyllic, hard to explain “to a seventeen-year-old without destroying the carousel of images I’d shared with him since his pre-school days.” Never mind the oddity of sharing college memories with a four- or five-year-old; the memories are at once hackneyed and strangely inauthentic:

Advertisement

Cambridge on rainy afternoons with friends, or in a blizzard when things went on as usual and the days seemed shorter and festive and all you wanted to imagine was tethered horses waiting to take you to Ethan Frome places; the Square abuzz on Friday nights; Harvard during reading period in mid-January—coffee, more coffee, and the perpetual patter of typewriters everywhere; or Lowell House on the last days of reading period in the spring, when students lounged about for hours on the grass, speaking softly, their voices muffled by the sounds of early summer.

Being taken by tethered horses to Ethan Frome places must be a first in Harvard and Cambridge annals, but there is much more that’s off-key in the account of this father-and-son visit. Perhaps the most comical exchange during this sentimental pilgrimage comes when they are at Lowell House, one of the river residences. As they contemplate the red-brick faux-Georgian structure, the father asks the son, “Didn’t [the house] remind him of a turn-of-the-century grand hotel on the Riviera?” The kid’s answer is spot on: “It’s a college dorm.”

The narrator does tell his son as they stand outside Café Algiers, a Brattle Street coffee shop that had been his hangout, that he ran into someone there one summer “who came so close to altering the course of my life that today I might not even be my son’s father.” The boy is “more than mildly miffed,” and the narrator explains that there had been days during his graduate studies when he would have wished to leave not just Harvard but the US:

I wasn’t even a citizen in those days and a side of me, just a side of me, craved to move back somewhere on the Mediterranean. This fellow was from the Mediterranean as well, and he too longed to go back. We were friends.

Harvard Square is not a campus novel. Its title notwithstanding, the university is only a pale backdrop. Instead, the central theme is the evolution of the friendship between the two men, and the narrator’s ultimate betrayal, which is incongruously likened to Saint Peter’s. We are told that the story begins in the summer of 1977, one of the hottest the narrator has ever lived through. Earlier that year he had failed the comprehensive examinations required of doctoral candidates. He will have another shot at them the following January, but there is no third chance. The strategy for success, for remaining in the grand world of Harvard that in his rational moments he covets, is to prepare by reading everything of significance in English and French seventeenth-century literature—his chosen area.

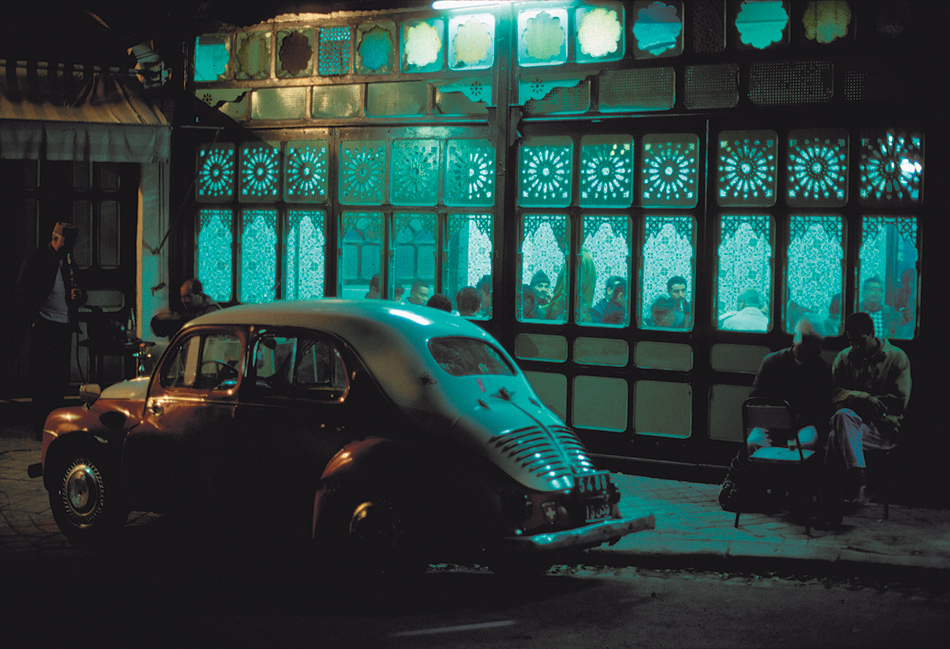

To add to his discomfort, he is broke. Covered with suntan oil, he does his reading on the roof of his building on Concord Avenue, downing Tom Collinses mixed with gin he had taken from a party given by his department. Occasionally he shares drinks with a bikini-clad graduate student neighbor also preparing for her comprehensives. Otherwise he reads at Café Algiers, making an iced coffee last two hours. It is there that he meets the friend who almost changed his life, a thirtyish Berber Tunisian cab driver who speaks French with a “Maghrebi” accent:

Primitive, yet completely civilisé. He crossed his legs in a very distinguished manner—but the look, the clothes, the hair were a ruffian’s.

The Tunisian is known as Kalaj. Why Kalaj? It’s short for Kalashnikov, a sobriquet earned by his brilliant rapid-fire repartee, but the tirades that so captivate the narrator—Kalaj’s imprecations against the ersatz nature of capitalists, Communists, whites, blacks, men, women, Jews, gays and lesbians, and everyone and everything else—aren’t very clever or funny, and no amount of insistence on their charm can make them such. It’s unfortunate, because Aciman has demonstrated that he is able, when writing about a milieu that is natural to him, to make a character’s diction beguiling.

There is a reason for the narrator’s fascination with the Tunisian cab driver on the lam since he jumped a navy ship in Marseilles: unresolved homoerotic attraction. He acknowledges it in a comparison he makes between himself and his friend:

I envied him. I wanted to learn from him. He was a man. I wasn’t sure what I was. He was the voice, the missing link to my past, the person I might have grown up to be if life had taken a different turn. He was savage; I’d been tamed, curbed. But if you took me and dumped me in a powerful solvent so that every habit I’d acquired in school and every concession made to America were stripped off my skin, then you might have found him, not me, and the blue Mediterranean would have burst on your beach the way he burst on the scene each day at Café Algiers.

Some months later, while a dinner party is in progress at the narrator’s apartment, Kalaj, terrified that he will be deported, shuts himself in the bedroom. The narrator checks on him in the darkened room and finds him on the bed, crying. “In an unexpected gesture,” he tells us,

I lay down right next to him, facing him, and put one arm across his chest. Only then did he reach out to hold my hand, and then, turning to me, put a leg around me and began to cradle and hug me, both of us entirely silent except for his muted sobbing. We said nothing more.

A counterpoint to the narrator’s crush on Kalaj is his fear of being compromised in the eyes of other graduate students or faculty members by being seen with the Tunisian. It’s not that he’s worried that, in the still-homophobic Harvard community of the 1970s, he might be tagged as gay. “Thank God,” says the narrator, “I hadn’t run into anyone from Harvard in his company…. I could just picture Professor Lloyd-Greville giving Kalaj the once-over before turning to his wife and saying, ‘He’s hanging out with drifters now.’”

The more Kalaj’s fondness for the narrator grows, “the more desperately I clung to the small privileges and to the tentative promises Harvard held out for me”; he rejects as inconsistent with those privileges the “other ways of living and doing things” Kalaj had been showing him. When the narrator acquires a girlfriend with rich and proper Boston Brahmin parents, and is invited to tea with them at the Ritz, all he can think of as the girl and he arrive at the hotel is:

Please, God, don’t let Kalaj’s cab pass by now, don’t let him pull over and speak to us, don’t let him be anywhere close…. I was ashamed of him. Ashamed of myself for being ashamed of him. Ashamed of being a snob.

Soon he finds himself wanting to be rid of Kalaj, even if that means deportation. When the fatal day comes, he never stirs from the Widener Library so that Kalaj will not be able to reach him by phone, and refuses to have a farewell drink with him that evening. Reflecting on his own cowardice—“Never had I sunk so low in my life”—the narrator feels

like someone who has been putting off dropping in on a dying friend. Each time the dying person calls him and asks him to come by for a few minutes, the friend, on the pretext of trying to lift up the sick man’s spirits, makes light of his worries. I’ll try to come tomorrow. “There may not be a tomorrow,” the dying man says. “There you go again. You watch, you’ll outlive us all.”

One would like the remorse so eloquently expressed to be genuine. But in fact the simile is a distracting echo of the famous scene that unfolds on the last pages of Proust’s Le Côté de Guermantes. Charles Swann, the lifelong friend of the Duke and Duchess de Guermantes, calls on them just as they are going out to dinner and, for the first time, reveals that he is gravely ill, the doctors giving him no more than three or four months to live. Bad timing! The duke is hungry and in a hurry. He dismisses Swann with a stentorian shout: Don’t let the doctors’ nonsense impress you! They’re nothing but donkeys. You’re as solid as Pont-Neuf. You’ll bury us all.

The other characters populating Harvard Square don’t do much to help carry the weight of this novel. The “girlfriends”—the narrator’s and Kalaj’s—are vapid: I found myself referring to them as number one, two, three, etc. The two Harvard faculty members and one faculty wife are unfunny caricatures. The departmental chairman, Professor Lloyd-Greville, comes in for particularly heavy drubbing. One evening, Lloyd-Greville, dining with a Parisian colleague and their wives at a restaurant, sees the narrator in the bar and asks him to stop by his table to say hello to his wife and friends. Lloyd-Greville had said nothing about joining them for dinner, and, in fact, the foursome’s first course has already been served. Nevertheless, the narrator finds that not being invited to pull up a chair and sit down is a snub so colossal that at once he hates “everything this side of the Atlantic,” and reflects that “[a] decade ago…none of them were good enough to step into my parent’s service entrance.”

Strange social standards seem to have prevailed in Alexandria, and strange manners taught to adolescents. One evening, after the narrator has dined with his Bostonian girlfriend and her parents at a fancy French restaurant, the girlfriend tells him that her parents “loved” him. Why? “They loved the way I’d complained there were no fish knives at [the restaurant]. It was typical of them to have noticed….” Telling their daughter that her swain was a conceited twerp would seem a more likely response.

Perhaps the lesson to be taken away from Harvard Square is that being down and out in Cambridge and Boston, and such activities as hanging around with taxi drivers and going to happy hours to fill up on fried chicken wings, don’t seem good subjects for Aciman. When the narrator says he couldn’t forget his days and evenings at Café Algiers because it was the only place this side of the Atlantic that “I could almost call home,” he unwittingly puts his finger on the problem: it wasn’t his home and memory can’t make it such, any more than Kalaj’s Mediterranean qualities and fulminations against phoniness can explain the narrator’s infatuation. In order to be convincing, Aciman would have had to be as frank about the narrator and Kalaj as he was about Elio and Oliver in Call Me by Your Name. Presumably that was not what he set out to do.

The writing in Harvard Square may be a symptom of his unease. In his other works Aciman has tended to overwrite; in this novel the prose is threadbare and marred by solecisms. For example, when Kalaj is busy charming a young woman, the narrator tells us

I interrupted their back-and-forth once or twice, and both times would have ruffled their seamless Mozart duet had either paid any attention.

Or apropos of Indian summer:

I liked the extended illusion of spring weather with its heady presage of summer oddly trailing on the last, first days of fall.

Or:

I walked by Berkeley Street. Nothing pleased me more than to pass by these old New England houses and be greeted by the beaming palaver of Anglo-Saxon housewives busily planting next spring’s bulbs.

And after a couple of hours at the girlfriend’s Brahmin parents’ house he remarks:

There was a moment at the party when I wished to undo my tie if only to let fresh air into my system….

It’s all a great pity. Aciman is a gifted and protean writer. One wishes him better luck next time.

-

*

Pour l’enfant, amoureux de cartes et d’estampes,

L’univers est égal à son vaste appétit.

Ah! que le monde est grand à la clarté des lampes!

Aux yeux du souvenir que le monde est petit! ↩