Religion, religion…. This is the battle cry of the feeble and the weak person who defends himself with it whenever the current threatens to sweep him away.

—Sayyid Qutb, 1938

Humanity will see no tranquility or accord, nor can peace, progress or material and spiritual advances be made, without total recourse to God.

—Sayyid Qutb, 1959

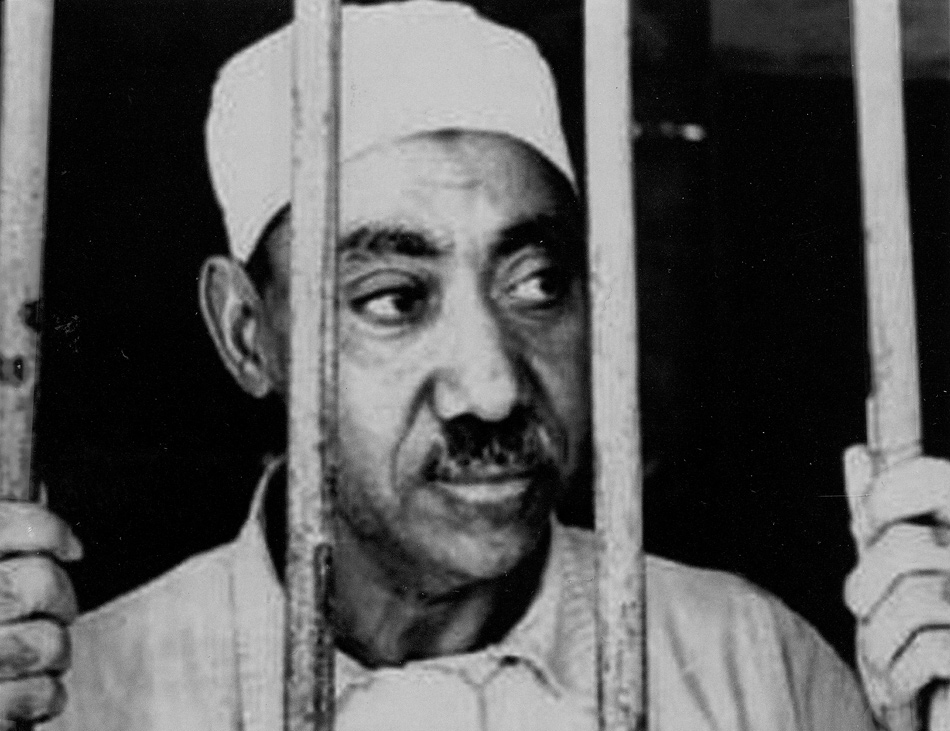

Few men have contributed so strongly to the tenor of modern political Islam as Sayyid Qutb, who died in 1966. Fastidious and shy in person, the Egyptian intellectual made an unlikely Savonarola figure. Yet his prolific writings, whose passion resonated amid the anti-imperialist ferment of the 1950s, grew increasingly strident in championing Islam as the cure to every ill of his age. Qutb’s peculiar fusion of romantic socialism with Muslim neopuritanism struck a chord that echoes loudly to this day.

Imprisoned by Egypt’s secular, army-backed regime along with thousands of fellow members of the Muslim Brotherhood, Qutb was executed in Egypt in 1966 for plotting against the state. His posthumous revenge has been long and sweet. Coming just months after Qutb was hanged, Israel’s crushing triumph in the Six-Day War dealt not only personal humiliation to his chief persecutor, President Gamal Abdel Nasser. It also discredited Nasser’s brand of Arab nationalism and strengthened those who, like Qutb, saw Egypt’s trials as divine retribution for straying from the faith.

Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, freed the imprisoned Brothers in the 1970s, prompting a split among Egyptian Islamists. A quietist mainstream focused on preaching, with the aim of transforming society from within. Activist groups argued instead, following Qutb, that change would come only through the deeds and example of a revolutionary vanguard. The jihadist assassins who felled Sadat in 1981 were acting upon Qutb’s dictum that even a nominally Muslim leader could be considered fair game, should he fail to impose their own narrowly defined form of “Islamic” rule.

Three decades later, the broad Islamist fraternity rode the revolution that toppled Sadat’s successor, Hosni Mubarak, to electoral success. Now deeply embedded in society and steeled in politics by years of oppression, the Muslim Brotherhood captured both Egypt’s parliament and presidency. Within the Brotherhood itself, hard-liners who are often referred to as Qutbists had succeeded not long before in purging the group of liberal dissenters. Muhammed Badie, the Brothers’ current Supreme Guide, had known Qutb well from the time they shared in prison in the 1960s. A top lieutenant of Badia’s, Egypt’s current president, Mohamed Morsi, has described Qutb as a thinker who “liberates the mind and touches the heart,” and who offers “the real vision of Islam that we are looking for.”

Further afield, Islamist parties of varied stripes now either dominate politics or represent the main challengers in nearly every Muslim-majority country. For many of these movements Sayyid Qutb remains an inspirational figure. The Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, himself translated several of Qutb’s books into Farsi, and revolutionary Iran commemorated his “martyrdom” on one of its first postage stamps. The current prime minister of Morocco, Abdallah Benkirane, whose party promotes a far more diluted and tolerant Islamism, has said that reading Qutb opened his eyes and changed his life.

But it is on the more violent fringes of the broad Islamist spectrum that Qutb’s influence has been most profound. His framing of the movement not merely as a struggle for reform but as carrying forward a perpetual war of good against evil encouraged the adoption of extreme tactics by some. Osama bin Laden studied for a time under Qutb’s admiring younger brother Muhammad, who fled Egypt for Saudi Arabia in the 1970s and taught for many years at a college in Mecca. Ayman al-Zawahiri, bin Laden’s successor as head of al-Qaeda, has said of Qutb that he “fanned the fire of Islamic revolution against the enemies of Islam at home and abroad.” The Egyptian’s writings have been a mainstay in the literature of Islamist guerrilla movements, from the Moro Islamic Liberation Front in the Philippines to al-Shabaab in Somalia.

Boko Haram, a jihadist group whose attacks in Muslim-dominated northern Nigeria have killed thousands since its founding ten years ago, expounds what might be described as a Qutbist philosophy stripped bare. Its name combines the Arabic word haram, meaning forbidden or religiously prohibited, with the pidgin term for book, in this case implying Western culture in general. The intellectual underpinnings for Boko Haram’s fanatical nativism derive from Qutb’s conclusion that building a Muslim utopia requires rejecting all that is external to Islam.

Needless to say, it stretches the imagination to ascribe to one man and his writings so profound, wide-reaching, and varied an impact. Sayyid Qutb had no such illusions about his own importance, and indeed would likely have been horrified to find his teachings used as justification for acts of mass terrorism. The story of his transformation from a typically pious provincial student alienated by the worldly ways of Cairo in the 1920s, to a combative critic, and then to an embittered and radical ideologue, suggests Marx or Engels more than Lenin or Mao. And by contrast to communism’s founding fathers Qutb was less an innovator, a theorist, or a brilliant opportunist than simply a product of his own times, his intellectual milieu, and his specific personal circumstances.

Advertisement

Still, his intellectual journey reveals much about the evolution of political Islam. Luckily, two excellent new books now fill what had been a large gap, in English at least, of scholarship on Qutb. Both books are are hefty and impressively researched. Both combine biography with broader histories that trace the sources of Qutb’s ideas as well as their impact, and both strain to be sympathetic and evenhanded. Yet there is less overlap than might have been expected.

The more insightful of the two is by John Calvert, a history professor at Creighton University, a Jesuit institution in Omaha, Nebraska. Calvert has also translated one of Qutb’s own earlier books, a rather charming memoir of his childhood,* which perhaps contributes to a finer understanding of his subject’s worldview and motives. He describes his biography as an attempt to hear the voice of Qutb, rather than to “regard his thought simply, and uncritically, as a modern pathology.”

Whereas Calvert focuses on the chronology of Qutb’s life and on the wider Egyptian setting, James Toth, an anthropologist at New York University’s Abu Dhabi branch, goes more deeply into Qutb’s intellectual contribution. His book provides a useful précis of the main themes that Qutb explored and the terms he introduced. This is no small feat, considering that the Muslim Brotherhood’s preeminent thinker penned countless articles and more than twenty books, one of them a six-volume commentary on the Koran.

Perhaps oddly for a man of such intensity, Qutb was a latecomer both to the Muslim Brotherhood and to Islamism. His early life and career followed a predictable path for a man of his times. Born in 1906 as the eldest son of a respected but declining family in rural Upper Egypt, he had the traditional religious education that was then the only kind available in his village. He had memorized the Koran before joining a newly opened government school.

A diligent scholar, Qutb won a coveted place at a state teacher-training college in Cairo. Egypt’s capital in the 1920s was a big, bustling city whose smarter quarters, their boulevards lined with cinemas, department stores, and café-bars, abutted medieval-looking slums. It was at once alluring and, owing to the privilege enjoyed by a nonchalantly cosmopolitan elite that disdained native customs, also repellent to the pious. Others of Qutb’s generation recalled the envy felt in his college for the prestigious Egyptian University, with its clubs and social polish, and instructors who taught in English and French. Inspired by such groups as the Boy Scouts and black-shirted Italian Fascists, but determined to exert native Egyptian pride, a fellow graduate of Qutb’s college, Hassan al-Banna, founded the Muslim Brotherhood in 1928.

With no money of his own, Qutb secured an administrative job in the burgeoning Ministry of Education. His father having died, the dutiful son brought his mother and sisters to Cairo. He was never to marry; his works of fiction hint at a timid squeamishness regarding women. In the 1930s Qutb plunged into Egypt’s lively intellectual life, making a small name for himself as a critic and minor poet. He was notably aggressive, dismissing writers he disliked as “flies” or “worms,” and attaching himself fiercely to one side of an ongoing literary dispute. But his opinions, increasingly tinged with trenchant calls for social justice and freedom from imperialist clutches, largely echoed prevailing fashions.

Amid fainter echoes of Marx, Bentham, and Mill, with their pragmatic appeals for greater humanity, rose a stronger drumbeat of romantic mysticism. As Calvert keenly notes, Qutb seems to have been strongly influenced by the school of Oswald Spengler, which posited the inevitable decline of the decadent, materialist West and the rise of a “spiritual” East. Such notions gave rise to a broad revival in Egypt of interest in the Muslim past, seen now through the new eyes of modern nationalism and expressed in a streamlined “modern standard” Arabic.

It was at this time, in fact, that the words “Islam” and, even more so, “Islamic,” came into wider Arabic use; in less contested times there had been no need to define the faith of Muslims in opposition to anything else. Toth notes that in 1940 Qutb wrote a scathing denunciation of Egyptian popular music. Censors should allow only spiritually exalted tunes, he said.

Advertisement

His drift toward a more strident nativism coincided with World War II. In the war years Britain, which had granted Egypt nominal independence in 1922, cited a mutual defense treaty to place the country under what amounted to a renewed military occupation. The humiliation instilled in many Egyptians a lasting anger. Qutb would later write of his horror at seeing that Allied troops “ran over Egyptians in their cars like dogs.” By the war’s end he had concluded that the West was morally bankrupt. “The Americans are no better than the British, and the British no better than the French,” he wrote in 1946. “They are all sons of a single loathsome material civilization without heart or conscience.”

The war in Palestine in 1948 dealt a further blow to Egyptian pride, and generated greater anger against the perceived corruption and weakness of Egypt’s government. Though neither Calvert nor Toth go deeply into this influence it seems likely that the creation of a Jewish state (and coincidentally also the “Muslim state” of Pakistan) helped push Qutb to what he saw as a final break with Western influence. From then on all his writings focused on Islam, in a long outpouring whose overall intent seemed to be to reconstruct the Muslim faith as an all-encompassing “system”—this being another Arabic neologism in regard to Islam—capable of filling a West-sized space.

As Calvert notes, Qutb was not alone in this effort. The roots of modern Islamism stretch back to the end of the nineteenth century and were propelled by the desire to address, and redress, the evident fact of the Muslim world’s weakness in the face of the expanding West. Two contemporaries that Qutb admired, the Indian Muslims Abu l-A’la al-Mawdudi (1903–1979) and Abu al-Hasan Ali Nadwi (1913–1999), were at the same time advocating a pan-Islamic revival, combined with a return to puritan ideals and a refreshed fighting spirit. A Muslim’s primary loyalty, they all believed, should not be to his homeland but to a wider Islamic nation. “When Qutb and Mawdudi compared Islam and other systems,” Calvert writes, “they did not compare it with Christianity, Judaism or Hinduism, but rather with competing ideologies of Communism, Capitalism and Liberal Democracy.”

Like his Indian colleagues, Qutb formulated his “system” around two central concepts. One of these they called hakimiy-y-a, a word that Toth translates as “dominion,” in the sense of God’s complete dominion over worldly affairs, with the Koran and the example of the Prophet, rather than man-made laws, providing rules to govern every aspect of behavior. The other term was jahiliy-y-a, which literally means “ignorance,” but had previously applied to the time of ignorance before the arrival of Muhammad’s message. In the Islamists’ new sense, the word applied also to everything in the contemporary world that challenged their Islamic system.

Qutb would later take this concept to dangerous extremes. But the most widely read book of his early Islamist phase was a treatise about the notion of social justice in Islam. Striking a theme that would permeate his later books, he suggested that, properly understood and applied, the Muslim faith provided ideal underpinnings for spreading freedom and equality—again, ironically, two terms not found in classical Islamic texts, and the positive value of which had been imported from Western thought.

It was just as these ideas weighed upon him that Qutb received a grant from his ministry to travel to America, ostensibly to study its methods of education. Egyptian scholars speculate that this unwonted burst of government generosity might have resulted from a desire to check the brooding intellectual’s radical drift, or simply to keep him out of trouble. At the time, Egypt’s relatively liberal, pre-Nasser government was locked in an increasingly nasty struggle with the Muslim Brotherhood that included the assassination of several officials by the Brothers, bombs directed by them against Jewish-owned businesses, mass arrests of Brotherhood members, and the assassination of Hassan al-Banna himself in February 1949.

Whatever the case, Qutb’s nearly two-year American sojourn, which has been well covered by several scholars, only deepened his hostility to the West. The prudish, dark-skinned Egyptian was appalled by what he saw as the lewdness of American women, but even more so by the racism that he encountered personally. On his return to Egypt his suggestion was that “we must nourish in our school age children sentiments that open their eyes to the tyranny of the white man, his civilization, and his animal hunger.” Neither Calvert nor Toth say whether Egypt’s Ministry of Education took up this advice, but following the July 1952 military coup that swept aside a shaky democracy, Egyptian schoolchildren were indeed inculcated with xenophobic nationalism.

The revolution that carried Nasser to power also, briefly, brought Qutb to his greatest public prominence. Steeped in the prevailing anti-imperialist, socially reforming spirit of the moment, the army officers now in charge at first saw Islamists, including the Muslim Brothers, as natural allies. In fact, just days before the coup, Nasser himself had discreetly met at Qutb’s house with several leading Brothers to ensure their support. The fiery intellectual was later invited to address the officers’ club, with Nasser again in attendance. Calvert quotes the American ambassador at the time noting a striking concordance between the new regime’s program and the Brothers’ views. Qutb himself was offered the post of leader of a new political party Nasser proposed to establish, having banned all the old ones.

This honeymoon was brief. In February 1953 Qutb officially joined the Brotherhood, which, in an indication of respect, appointed him head of its propaganda department. The move for Qutb marked both an act of political commitment and a rejection of the military regime that he had begun to suspect, correctly, intended only to manipulate the Islamists in order to consolidate Nasser’s control. Muslims must unite, he declared at the time, and no movement other than the Brothers had the strength to stand up to “the Zionists and the colonialist Crusaders.”

By 1954 the Brothers’ ties to the regime had soured to the point that a young member pulled out a pistol at one of Nasser’s rallies and tried to shoot him. Later Egyptian accounts suggest that the would-be assassin may have been encouraged by the regime’s own agents, for the outcome was a vicious police clampdown on the group. Six of its leaders were hanged as conspirators, and Qutb himself was condemned to fifteen years’ hard labor.

He remained in prison until 1964, witnessing appalling cruelty, including torture, the use of dogs to torment prisoners, and the machine-gunning of a group of Brothers who had ostensibly attempted to escape. Briefly released following pleas from the president of Iraq, whom Nasser was keen to cultivate, Qutb was rearrested in 1965 in a renewed sweep of Brothers, some of whom had been stashing arms for a planned revolt.

It was in prison that he completed his lengthy Koran commentary, and also wrote his most famous political tracts. While being steeped in the scripture he had loved as a child gave his words an incantatory, exhorting tone, the experience of repression fired an infectious rage. Jahiliy-y-a, or ignorance, he now declared, referred to any society “which does not dedicate itself to submission to God alone.” Since even such a Muslim society as Egypt’s had proved itself unwilling to imbibe the “medicine” of pure Islam, he said, pure Muslims must form a pious vanguard (again, a borrowed concept) to show the way, by jihad if needed.

The details of how an “Islamic” system of government, or economy, or sharia laws should work were not important, he argued. The thing was to create an Islamic state. All else would follow. The rhetorical question Qutb asked was powerful in its simplicity: “Who knows better, you or God?” The obvious answer to millions of Muslims ever since has been that an all-knowing God revealed his irrefutable will in the words of the Koran.

In subsequent years the Muslim Brothers were to distance themselves from the more radical implications of Qutb’s ideas, and particularly his contention that fellow Muslims outside the Brotherhood could be condemned en masse as hypocrites and unbelievers. Many Islamists today have never read his books. Yet the paranoid style of Qutb, and his utopian vision, still permeate Islamist thought.

-

*

Sayyid Qutb, A Child from the Village, translated by John Calvert and William Shepard (Syracuse University Press, 2004). ↩