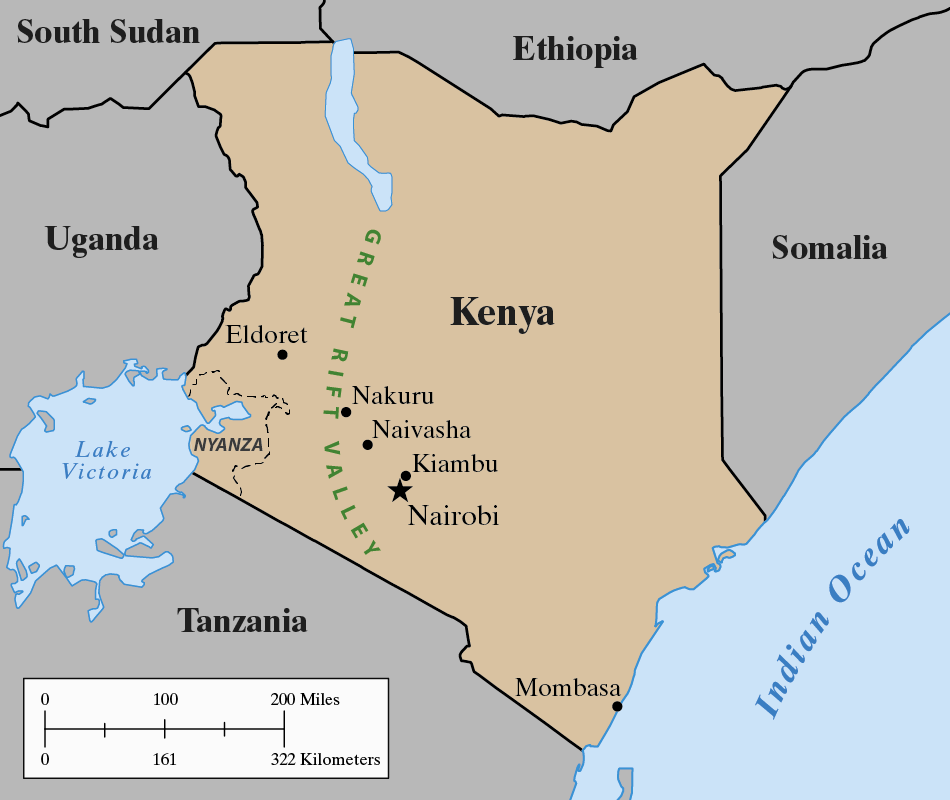

One morning in mid-March, at the beginning of the Kenyan rainy season, I drove to Kiambu, the ancestral homeland of Uhuru Kenyatta, the country’s newly elected president. Thirty minutes northeast of Nairobi I turned off a new six-lane highway and followed a country road across a fertile plateau. Coffee bushes glistened after a morning rainfall. Banana trees and plots of maize climbed the slopes of ravines. Mile after mile of new streetlamps bordered the road. “It is rare to see these lights in rural Kenya,” my companion, a reporter named Dominic Wabala, told me, attributing the local improvements in part to Kenyatta’s huge fortune.

Soon we came to Ichaweri, near the birthplace of Kenyatta’s father, Jomo Kenyatta, the rebel leader and first president of Kenya, who died in 1978. The thirty-one-acre farm is one of many valuable properties that Kenyatta accumulated during his fourteen-year presidency. A driveway led to the guarded front gate, which was flanked by traditional Kenyan shields—black, red, and white ovals crossed by two spears—mounted on stone pillars. A fig tree, or mugomo, considered sacred by the Kikuyus—the Kenyattas’ tribe, which led the Mau-Mau uprising against Britain in the 1950s and which makes up about 22 percent of Kenya’s population—towered over the entrance. The Kenyatta family’s farmhouse, topped by an orange-tile roof, stood half-hidden behind a thick hedge. “It is best not to stop here,” Wabala told me, as I slowed down for a longer look. Wabala was worried that we might be detained and interrogated by the Kenyattas’ round-the-clock guards.

Just up the road in Gatundu, I spoke with Francis Maina, a journalist and an ardent Kenyatta supporter. He said that Kenyatta, the member of Parliament from the area, often dipped into his own pocket to help needy constituents. Once, Maina said, he flew a dying girl and her mother to India so that the girl could have heart surgery. “He piped water to the villages, built health centers, got poor families scholarships,” using both his own money and a discretionary fund provided to all members of Parliament, he told me. During the election campaign, Kenyatta’s opponents attacked him for holding an inequitable share of the country’s wealth. In a country plagued by a hunger for land, the Kenyatta family’s holdings are said to be the equivalent of Nyanza Province, a 6,200-square-mile region around Lake Victoria in western Kenya. Maina said that the allegation was “garbage…. People have been duped into believing that.”

Since independence in 1963, Kenya’s politics has been largely based on competition as well as alliances among the country’s four dozen tribes. Besides the biggest, the Kikuyu, they include the Luhya, who comprise about 14 percent of the total population; the Kalenjin, 13 percent; and the Luo, 10 percent. The tribes speak their own languages among themselves and have their own hierarchies of leadership, but they also participate in national politics. It has been customary for Kenya’s leaders to favor members of their own ethnic groups with land, import licenses, and other perks—and to shut out nearly everyone else. After the original uprising against the British was led by the Kikuyus, Jomo Kenyatta, as first president, made many of his fellow Kikuyus rich before he died in 1978. He was succeeded by his vice-president, Daniel Arap Moi, a Kalenjin from the Rift Valley, whose twenty-four-year autocratic rule was marked by alliances with other Rift Valley ethnic groups, as well as the pastoral Massai tribe, and the near-exclusion of the Kikuyus.

Moi was forced into retirement in 2002, and, following Kenya’s first free presidential election, power passed back into the hands of the Kikuyus under the new president, Mwai Kibaki. He remained in office for a decade, also enriching his Kikuyu tribal allies and excluding rival groups. Kenya’s new constitution of 2010 limited its president to two five-year terms, which set the stage for the 2013 election, pitting Jomo Kenyatta’s son, Uhuru, against Raila Odinga, a longtime opposition leader from the Luo tribe.

Kenya’s presidential election in March was supposed to display the country’s progress into the modern, post-tribal era—and Kenyatta, fifty-one, was said to symbolize a transformation. Photogenic and rich, a graduate of Amherst, he is part of a new generation of Kenyan elite who drive their SUVs and Mercedeses on Nairobi’s new superhighways, and sip cappuccinos at establishments such as Artcaffé in the city’s sleek shopping malls.

In diplomatic cables from June 2009 released by WikiLeaks, the US ambassador to Kenya, Michael Ranneberger, praised Kenyatta as a potential reformer. His “enormous” wealth would obviate the need for him to indulge in corruption. Ranneberger noted that Kenyatta “drinks too much” and “is not a hard worker,” but is “bright and charming, even charismatic.” Maina Kiai, the director of InformAction, a grassroots organization founded in 2010, and the former chairman of the Kenyan National Commission on Human Rights, who has known Kenyatta for years, says he “laughs, cracks jokes, drinks a lot. He is almost a hedonist. He is like George Bush before he became saved.”

Advertisement

Yet Kenyatta has been shadowed by a darker reputation. In March 2011 he was indicted by the International Criminal Court on charges of crimes against humanity; he was accused of organizing and funding the murders, rapes, and displacements of thousands of his opponents—many from other tribes—in the aftermath of Kenya’s December 2007 election, which was won by his political ally, Mwai Kibaki, a fellow Kikuyu. (Raila Odinga, from the Luo tribe, was the loser.) It was alleged in complaints to the ICC that Kenyatta was outraged by a wave of attacks that had been carried out against Kikuyus after Kibaki was reelected under suspicious circumstances, and that Kenyatta turned to violent criminal gangs of Kikuyu youths to exact revenge. Despite dozens of filings by Kenyatta’s lawyers aimed at stopping or slowing down the judicial process, his trial in The Hague is scheduled to begin in July.

This raises the unsettling prospect that the leader of one of Africa’s most important nations—the regional headquarters of the United Nations and World Bank, and a listening post for monitoring al-Shabab, the beleaguered but still dangerous al-Qaeda affiliate in neighboring Somalia—will have to conduct the country’s business while answering charges from the dock. Raila Odinga, the sixty-eight-year-old opposition leader, who mounted an unsuccessful challenge to Kenyatta in this year’s election, said during a televised debate, “I know it’s going to cause serious challenges to run the government by Skype from The Hague.”

Kenyatta’s indictment and the showdown with the ICC are uneasy reminders of a past that Kenyans would rather forget. For all of his modern trappings, say his critics, Kenyatta is in many ways a throwback to his predecessors: his father; Daniel Arap Moi, the country’s dictator for twenty-four years; and Moi’s successor, Mwai Kibaki. All three presidents favored their own ethnic kin at the expense of other tribes, and all helped sow the seeds of the 2007–2008 bloodletting. “His approach is, get your home crowd behind you, and then start talking and negotiating with others,” says Maina Kiai. “If you first make sure you are ethnic king, then you will always place your constituency first. That is not the definition of a reformer.”

Kenyatta himself has not been seeing any foreign reporters, I was told. One sunny afternoon, I sat on the terrace of a Lebanese-Japanese restaurant with one of the president-elect’s closest friends. He was talking to me at the request of a London-based public relations firm, BTP Advisers, which Kenyatta had hired to play down the controversy surrounding his indictment. (Among BTP Advisers’ other clients is Paul Kagame, the Rwandan president, who has been accused, among much else, of backing a rebel group responsible for human rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.) Kenyatta was vacationing at a family villa on the coast near Mombasa, and “isn’t yet ready to do interviews,” managing partner Mark Pursey had told me.

The friend I talked to, who asked not to be identified, came to know Kenyatta in the early 1970s at St. Mary’s School, a private day school founded by the Catholic Archdiocese of Nairobi in 1939. Set on eighty-five wooded acres in the affluent Lavington neighborhood, the school attracts the sons and daughters of Kenyan cabinet ministers, high-ranking civil servants, and ambassadors. (Kenyatta was raised a Catholic by his mother, but the school is open to all.) Kenyatta was remembered as a charming, popular student who played rugby, served as a prefect, and socialized on weekends with a tight-knit group of fellow privileged youths, sometimes at State House, the sprawling villa on a hill above Nairobi from which his father ruled. In 1980, two years after his father’s death, Uhuru Kenyatta left Kenya to attend Amherst.

At Amherst, Kenyatta shared an off-campus apartment with three other Kenyan students, studied economics and politics, and took an interest in third-world development. Kenyatta gave little evidence of his lineage, except for the photo of his father that hung in his room. He drove a secondhand Toyota that he had purchased for $2,000, and frequently was visited by his younger brother, Muhoho, who was attending Williams, as well as his mother, Mama Ngina, who would fly in from Kenya and stay for a month at a local hotel. During Thanksgiving and spring breaks, Kenyatta and his roommates invited to Amherst Kenyan students from around the US who had nowhere else to spend their holidays, charging them $20 each for “booze and food.” Some students balked. “Uhuru didn’t like controversy, so he would say, ‘You take care that,’” remembers one of his roommates.

Advertisement

Kenyatta returned to Kenya in the mid-1980s and helped reorganize the family businesses, selling off land and developing Brookside, a dairy company, and Wilham Kenya Ltd., which has grown into one of Kenya’s biggest horticultural firms. His first entry into politics came in 1990, after the Kalenjin Daniel Arap Moi jailed a prominent Kikuyu businessman, Kenneth Matiba, who had challenged one-party rule. “We all knew Matiba personally,” Kenyatta’s friend told me. “He was a father figure to us, a close friend of our parents…. We said, ‘listen, this is getting out of hand.’” Kenyatta and several other sons of Kenyan leaders published an open letter in newspapers addressed to Moi, calling, the close friend said, “for multiparty democracy.” Maina Kiai has a different recollection. He says there was no mention of multipartyism in the letter: “They were scared shitless of Moi. They did not go as far as they should have.”

Moi did agree to multiparty elections in 1992, then employed fraud and intimidation to guarantee himself a victory. He also recognized Kenyatta as an up-and-comer—an influential Kikuyu whom he needed to have on his side. After Kenya’s independence in 1963, Jomo Kenyatta had expropriated land in the Rift Valley and moved many Kikuyus to the region. Local ethnic groups, including Moi’s Kalenjins, sometimes attacked the Kikuyu interlopers and drove them from their land. Moi and his party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), had little Kikuyu support.

In 1997, Kenyatta ran unsuccessfully for Parliament in his home constituency as the candidate of KANU. (Even though it was a predominantly Kikuyu district, his association with Moi caused him to go down in humiliating defeat.) Five years later, Moi was obliged to step down after a quarter-century in power, and he backed Kenyatta as KANU’s presidential candidate against Mwai Kibaki, the consensus candidate of a broad opposition movement, and another Kikuyu.

During this campaign in 2002, I was told, Kenyatta had the support of a secretive, violent Kikuyu organization—the Mungiki—that had originated in rural areas in the 1980s and migrated to Nairobi a few years later. The Mungiki operated protection rackets in the slums, recruited boys with absent fathers, and administered blood oaths to new members. “The Mungiki are wild guys, village thugs, who extort more from the Kikuyu than from anyone else,” Kenyatta’s friend told me. During the 2002 campaign, according to witnesses, the Mungiki held at least one large demonstration in Nairobi in support of Kenyatta. Although the government regarded the Mungiki as criminals, “Moi allowed them to operate freely as part of his strategy to have Kikuyus support Uhuru as his candidate,” says Ndung’u Wainaina, director of the International Center for Policy and Conflict in Nairobi.

Kibaki won handily, and Kenyatta entered Parliament as the leader of the opposition. Meanwhile, ethnic tensions were growing. Kibaki filled his cabinet with fellow Kikuyus—known as “the Mount Kenya Mafia”—who were eager to enjoy the spoils of power after years of being excluded by Moi. During Kibaki’s tenure, one of the worst financial scandals in Kenyan history took place, the so-called Anglo Leasing scheme. Close associates of Kibaki siphoned hundreds of millions of dollars from the Kenyan treasury through inflated no-bid contracts to a phantom corporation. Kalenjins, Luos, and other groups were left out in the cold.

On December 30, 2007, the Kenyan Electoral Commission declared Kibaki, the incumbent, the winner over the Luo Raila Odinga in the just-completed presidential election. International observers said that they had been denied access to polling stations, and there were widespread and credible reports of extensive ballot box s tuffing, falsification of returns, and other instances of fraud. Kibaki was hastily sworn in as president, and ethnic violence opposing him broke out. Many Luos (the tribe of Barack Obama’s father) believed that they had been robbed of a victory, and mobs of young Luo men with crude weapons began attacking Kikuyus in the Rift Valley and other areas.

The Waki Report, a comprehensive study of the violence released in the fall of 2008, quoted a Kikuyu survivor in the town of Eldoret:

Some Nandi [a Rift Valley ethnic group] were running after people on the road. I ran away with my children. I saw a man being killed by cutting with a panga and hit by clubs when I was running…. My last born child fell a distance away from my arm, was hurt, and was crying. Some people were running after me and when I fell, two men caught me. They tore my panties and they both raped me in turn.

Harun Ndubi, an attorney and a human rights activist in Nairobi, told me that in early January 2008, while Luos and their tribal allies were hunting down Kikuyus and killing them, he met with James Maina Kabutu, a self-described member of the Mungiki who was now willing to denounce both the secret organization and Kenyatta. Maina Kabutu claimed that he had attended meetings in State House between Mungiki leaders and high-ranking politicians, including Kenyatta, to plan the retaliatory killings of Luos and Kalenjins. “He also mentioned that Uhuru had funded some of the Mungiki people [and had] participated in a meeting [with the Mungiki] at the Nairobi Club,” a private club established in 1901 and popular among Kenya’s governmental elite.

Human Rights Watch says that in January 2008 the Mungiki hacked Luos and others to death in the Rift Valley’s main town, Nakuru. They forcibly circumcised others, and burned to death nineteen people, including women and children, in a house in Naivasha. More than five hundred people died in the Mungiki-sponsored violence. The close friend of Kenyatta’s acknowledges that the organization regarded him as their “spiritual leader.” But he says that in speeches in Limuru and elsewhere, Kenyatta urged people not to retaliate: “He was telling people that it can’t be an eye for an eye.” Maina Kabutu fled to Tanzania, then to the United States, where in a sworn statement before the International Criminal Court he said that Mungiki had been deployed to the Rift Valley and other areas “to defend our people.”

In March 2011 the International Criminal Court indicted Uhuru Kenyatta, then serving as finance minister, and three other Kenyan political figures for the violence of 2007 and 2008. The indictment drew on the testimony of several eyewitnesses, including Maina Kabutu. The charges said that

there are reasonable grounds to believe that indeed Kenyatta…organized and facilitated, on several occasions, meetings between powerful pro-[Party of National Unity] figures and representatives of the Mungiki.

In addition, Kenyatta “supervised the preparation and coordination of the Mungiki in advance of the attack [and] contributed money towards the retaliatory attack perpetrated by the Mungiki in the Rift Valley.”

In the months before the March 2013 election, Kenyatta portrayed the ICC as a tool of Western governments. He exploited Kenyans’ growing pride in their country and lingering resentment about interference by the United States and Great Britain. In a bold stroke, Kenyatta chose as his running mate William Ruto, a charismatic Kalenjin who had been indicted by the ICC for organizing attacks against Kikuyus in the post-election killing spree. The pair presented their Jubilee Alliance as a gesture of reconciliation, though one observer I talked to said they believed it would “inoculate” them against an ICC trial. The court, they believed, was unlikely to defy the will of the Kenyan people by arresting its two elected leaders.

One month before the election, the US Assistant Secretary of State Johnnie Carson warned Kenyan voters that “choices have consequences.” The warning, observers say, backfired. “Kenyans were saying to themselves, ‘Why should we be dictated to?,’” I was told by Mwenda Njoka, the managing editor of The Standard, one of Kenya’s largest daily newspapers. The journalist I met in Gatundu, Francis Maina, summed up the attitude of Kenyatta supporters toward the court. “The charges are framed up,” Maina told me. “The masters, the Western powers, have a desire to meddle in Kenya’s affairs.”

Kenyatta’s defenders included Jendayi Frazer, who served as US assistant secretary of state for African affairs at the time of the 2007 election, and who has become an opponent of the International Criminal Court. The ICC, she told me, was being used by the US and British governments to undermine Kenyatta and strengthen Raila Odinga, their preferred candidate. “The US government, which is not even a signatory to the ICC, uses this flap around Kenyatta’s head to say that the Kenyan people should not elect him, and that’s inappropriate,” she said.

Frazer insisted that the ICC had no business looking into a matter that should have been the responsibility of a domestic court. “You don’t want to minimize the number of people who lost their lives,” says Frazer, “but post-election violence of a few weeks is not on the scale of genocide.” As it happened, Kenya’s Parliament had refused to authorize an independent special tribunal to investigate the post-electoral violence, a failure blamed by US Ambassador Ranneberger on Kenyatta’s “working behind the scenes” to undermine the initiative.

On a rainy afternoon, ten days after the presidential election, I wandered through the Nairobi slum called Kibera, one of the largest in East Africa and a stronghold of Raila Odinga. Kenyatta’s victory, certified by the electoral commission, was facing legal challenges by Odinga and several independent groups, and Kenyans were waiting for the Supreme Court to decide whether to nullify the result and call for a new vote. I parked the car on a muddy lane near the primary school where Odinga had voted, and walked past a tin-roofed market and a shabby cybercafé. In front of a stand for matatus—Kenya’s ubiquitous, unregulated minibuses—I met a driver, Moses Otieno Oguto, from the province of Nyanza, Odinga’s birthplace. In January 2008, after Kibaki declared himself the winner, Oguto had watched police shoot down Luo protesters in the alleys of Kibera. “People died in front of me,” he said. “I don’t want this to happen again.”

Kenya’s election was supposed to be a showcase for the technological advances that the country had made, as well as its commitment to transparency. A broad-based new electoral commission introduced features including biometric voter identification kits and an instantaneous reporting system by which officials at each of Kenya’s 33,000 polling stations could dispatch the results by mobile phones over a secure server to a central registry in Nairobi. But the entire system crashed on election day, forcing officials to revert to old methods: tabulating the votes on paper registration sheets, and sending them by courier to Nairobi. Odinga and his supporters claimed that many of the sheets were tampered with, and also charged that Kenyatta made use of thousands of phantom voters, allowing him to push his total to just above 50 percent.

I asked Oguto, the matatu driver, how the residents of Kibera would react if the Supreme Court ratified Kenyatta’s victory. “There won’t be problems this time,” he assured me. In the same breath, he admitted, “I do not trust Uhuru, but there is nothing that I can do.”

“We trust Uhuru,” a Kikuyu driver, who gave his name only as Ronald, shot back.

“We don’t,” said another Luo. “We refuse to trust him.”

Wabala, the journalist, pushed me into our vehicle as the men argued. “Kenyans are seething inside,” Wabala told me. “It is a time bomb waiting for a trigger.” According to the Daily Nation, Kenya’s mobile phone companies were scrutinizing text messages for inflammatory words such as “kill,” and were blocking 300,000 “hate texts” per day.

On Saturday, March 30, Kenya’s Supreme Court certified Kenyatta’s victory. There was a smattering of protests, but Odinga accepted the verdict and the country remained quiet. Many Kenyans wondered whether the ICC fracas would blow over. “Witness Number Four”—James Maina Kabutu—a key figure in the case against Kenyatta, had recanted his testimony. ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda had been obliged to drop all charges against one of Kenyatta’s co-defendants, Francis Muthaura, the head of security forces at the time of the 2007–2008 violence. Kenyatta’s allies were predicting that the case against him would soon collapse. “It is a weak case and it always has been,” Jendayi Frazer told me. At The Hague, Bensouda insisted that she still had enough evidence to prosecute Kenyatta.

Harun Ndubi, the human rights lawyer, told me that he wasn’t surprised by the turn of events. Maina Kabutu had called him often in recent years, and “told me that he was being threatened, he was pressed by Mungiki people who said they knew where his mother lived, and did he want to see his mother’s head in an envelope.” Western diplomats say that the Kenyatta camp has been tracking down witnesses, trying to intimidate them, and, more often, buying their silence. Kenyatta’s allies dismiss the allegations as groundless.

When I met with Maina Kiai, the founder of the Kenyan National Commission on Human Rights, at a café, he told me that he feared that Kenyatta would start cutting back the reforms—including the freedom to oppose the rulers—that have changed the face of the country since the collapse of Moi’s one-party state in the early 1990s. “We can see them circling the wagons, telling foreign journalists to get out, saying that civil society is evil,” he told me. “We fear a crackdown.”

Kenyatta, meanwhile, flew back from the beach to prepare for his inauguration on April 9, in a stadium on the city’s outskirts, amid evidence that a diplomatic thaw had already begun. On March 30, following the Supreme Court decision, British Prime Minister David Cameron’s office issued a statement congratulating Kenyatta. The prime minister, the statement said, “looked forward to working with the President-elect’s new Government to build on [our] partnership, and to help realise the great potential of a united Kenya.” It was a telling shift from weeks earlier, when the British government stuck to a policy of no more than “essential contact” only with the men indicted by the ICC, and after Kenyatta’s victory on March 4, refused even to mention his name.

—April 10, 2013