To walk into the first few rooms of the exhibition “Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity,” now at the Metropolitan Museum, is to allow oneself to be immersed in the sweetness of life in the Belle Époque. On the walls, one finds a ravishing woman in pink, painted by Mary Cassatt (Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge), who smiles at the spectacle that surrounds her and also, one might say, at herself; a young woman dressed by Manet in sumptuous black, the polar opposite of mourning (The Parisienne), is the very picture of self-confidence; young women in white or pink are posed in gardens by Monet (Luncheon on the Grass) or we see them emerging from the shadows of the woods (Renoir’s Lise). The only soldier to put in an appearance here, depicted by James Tissot (Frederick Gustavus Burnaby), is shown stretched out languidly on a white couch, cigarette in hand, dress tunic and parade helmet casually tossed on a sofa upholstered in a floral fabric, and is so distinctly unwarlike that he might have been looked on approvingly even by Baudelaire, who detested the army.

Display cases contain lovely vintage costumes and a charming array of accessories. Impressionism, if viewed in fashion terms, becomes a runway presentation of evening gowns, silky, translucent peignoirs, dresses to be worn in the countryside, beribboned children’s outfits, and beautifully cut men’s suits. Still, what makes the exhibition so interesting is less the intersection of art with fashion than the concept of the modernity of art as it was understood by the artists of the last half of the nineteenth century.

The same exhibition was seen last year at the Musée d’Orsay, but with a substantial difference. In Paris, the chief focus was on decor and clothing, and the title of the show, “L’Impressionnisme et la Mode,” clearly emphasized that connection. The curators of the Metropolitan Museum, on the other hand, wisely chose to add a third dimension. Only fifteen or so mannequins have been placed in the galleries so as not to clutter the show. The display cases placed along the walls containing accessories—corsets, umbrellas, or hats—and the photographic panels do not interfere with the enjoyment afforded to a lover of pure painting. And in New York, the exhibition is called “Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity.”

A telling decision: in fact, the link between fashion and Impressionism is tenuous, verging on the deceptive. This is only in part because the dresses in their display cases are rigid museum pieces in the most static sense of the term, whereas the same dresses depicted on canvas are luminous, changeable, inseparable from the movement of the women wearing them. It is also because details are such an essential part of any elegant dress—it is the shape of a button, the placement of a pleat, the delicacy of an embroidery, the perfection of the fini (to use the language of an haute couture atelier) that determines the quality of a dress—whereas Monet, Renoir, or Manet worked first and foremost to evoke an attitude, an impression, the play of light on a fabric. This means, in fact, that they were working in the unfinished, the non-fini. This is diametrically opposed to what we find in a portrait by Ingres, who was so zealous about depicting his model’s clothing in exacting detail; their canvases invite the imagination to finish the painting.

The only painter of fashion whose work is on display in the show is Tissot. He was so captivated by the intricacy of one dress in particular that it appears, reproduced with the precision of a fashion photograph, in two of his paintings. And his renowned portrait of a group of clubmen, The Circle of the Rue Royale, is a wonderful catalog of hats, waistcoats, capes, and accessories, so detailed that Proust was able to borrow—as he admitted in a passage in In Search of Lost Time—the gray silk top hat worn by one of the gentlemen, Charles Haas, and place it on the head of his character Charles Swann, the elegant member of the Jockey Club.

Still, Tissot did not paint with the relaxed freedom or the distance of a genuine Impressionist, whose originality, notably according to Zola, came from the fact that he refused to create a

painting of details…. In order to render [a character] as he saw him, he need not paint him with every last crease of flesh, but instead alive in his posture, with the vibrant air that surrounds him.1

One must paint like Manet, Degas, Bazille, or Renoir when they depict their wives or friends: Suzanne Manet, captured upon her return from an outing, catching her breath, her hat perched on her head, the ribbons untied and loose, her feet, shoes still on, propped on her blue sofa (Madame Édouard Manet on a Blue Sofa); Berthe Morisot, with her intensely serious expression, depicted by Manet sprawling on a brown sofa beneath a print by a Japanese artist (Repose); her sister, placed by Degas in the living room of their parents’ home, posing without finery, without jewelry, calm, remote, and enigmatic (Madame Théodore Gobillard); Renoir, caught by Bazille, carefree, in a very natural pose, legs hiked up on the chair as if he were an urchin (Pierre-Auguste Renoir); or Madame Charpentier, painted by Renoir, in her Japanese-style living room, surrounded by her furniture and her knickknacks, one of her children perched on the family dog, around whose neck someone has tied a polka-dot scarf. “Talk, laugh, move around. You will look real only if you remain natural,” Manet often told his sitters.2

Some fifteen years earlier, in 1863, Baudelaire made clear what he meant by modernity in painting in a series of articles he wrote for Le Figaro. The modern artist resolutely turns his back on the past (and therefore on traditional subjects, either religious or historical), choosing instead to paint his contemporaries. He

has a spirit of a mixed nature, that is to say, a strong literary element enters into it. Observer, flaneur, philosopher…he is most like a novelist or a moralist. He is the painter of both the passing moment and everything in that moment that smacks of eternity.3

Novelists of the time so clearly recognized their affinity with artists that they would often draw inspiration from a painting or even, in certain cases, from an artistic technique. In Balzac’s case, for instance, Baudelaire noted that

his prodigious taste for detail…forced him however to lay greater emphasis on the most important outlines, in order to preserve the overall perspective.4

It is true that the camaraderie and the exchanges between writers and painters attained an unequaled intensity in nineteenth-century France. This was only in part because during that period Stendhal, Théophile Gautier, Baudelaire, the Goncourt brothers, Zola, Huysmans, and Mallarmé, to mention just the most illustrious names, all were regularly writing art criticism; it was also because of the direct influence that painters exerted over writers. Certain of Balzac’s caricatural descriptions owe a great debt, by his own admission, to the coded visual language that illustrators and caricaturists frequently employed, incorporating plants and animals in drawing human figures. Cousin Pons, the great collector of the Comédie Humaine, with his face flattened into something resembling the shape of a pumpkin, the illustrious Gaudissart with his pear-shaped belly, or Madame Vervelle, a customer of the painter Pierre Grassou, whose feet were topped by rings of fat above the patent leather of her shoes—none of them would have existed had not Balzac so admired Monnier, Gavarni, and Daumier.

Zola was much more deeply involved in the artistic life of his time than Balzac, first of all because of his work as a journalist, his activism in favor of the new school of art, and the omnipresence of modern Paris in his novels (a subject that he shared with the artists of his time), but also because of the unmistakably reciprocal current of influence flowing between him and Manet, especially in the conception of Nana.

In the painting reproduced and analyzed in considerable detail in the exhibition catalog,5 Nana, a plump young blonde, dressed in only a blue satin corset, a translucent petticoat, a pair of embroidered silk stockings, and a pair of high-heeled pumps, powders a carefully made-up face in front of a gentleman in a dress suit whose gaze is fixed on the voluptuous line of her hips. She is not naked, she is simply not dressed; and her mocking and mischievous smile leaves no room for doubt about the sort of young woman she is. The painting was refused at the 1877 Salon of Paris as an “outrage to morality.”

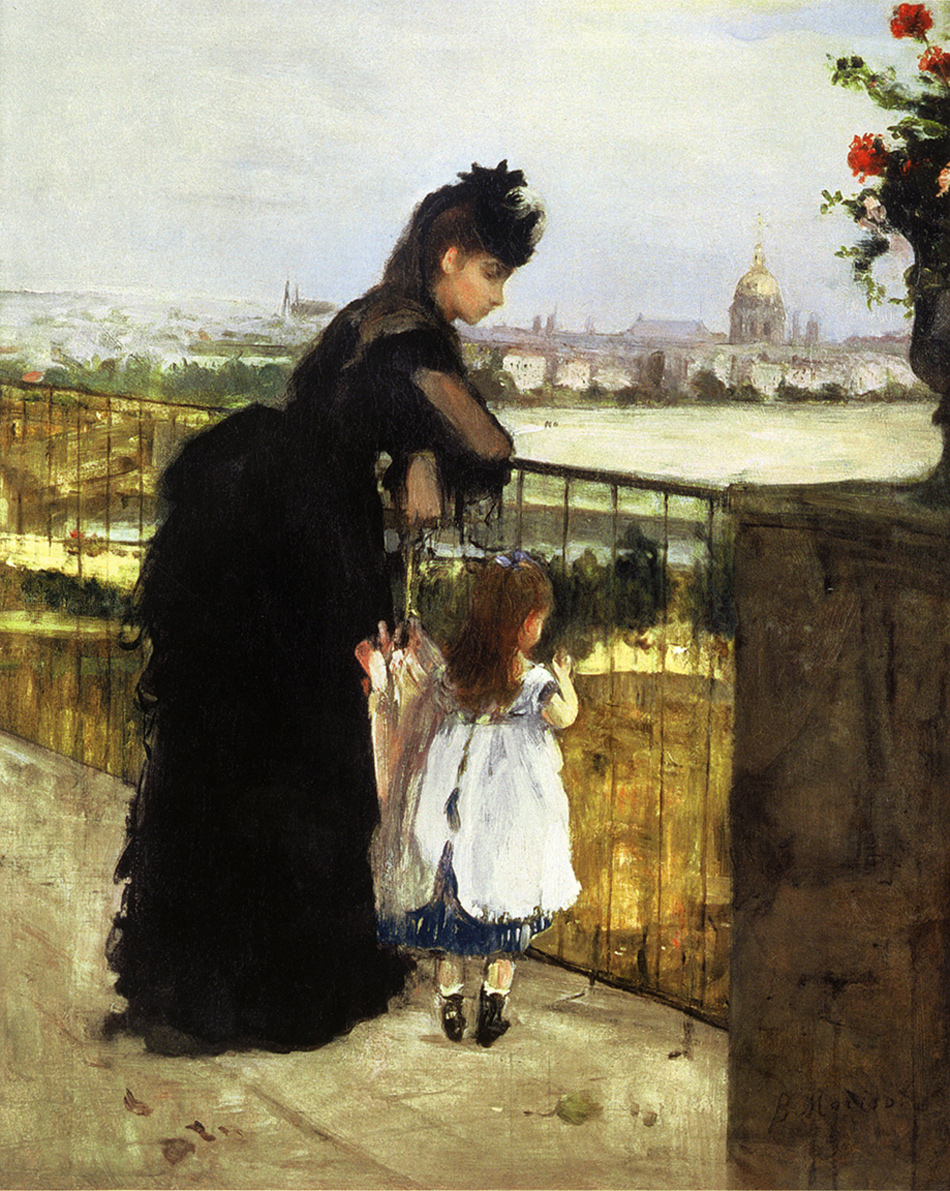

The subject of the prostitute, which Degas would go on to treat more brutally in his monotypes depicting actual brothels with fully dressed and behatted gentlemen examining half-naked women lolling on sofas, was a timely one. Manet took both the title and the subject of his painting from Zola, who, in L’Assommoir, described a young and depraved Nana at the beginning of her career, her mind already made up to live off her charms. Manet, in 1877, envisioned her as a Parisian tart, an ironic tease and, for the moment, triumphant. Zola took up the story again, finishing it three years later, in his novel Nana. While in the case of Manet’s painting of the young courtesan the painter was inspired by the writer, the opposite was true with Berthe Morisot’s On the Balcony: there Zola took his inspiration from the painting.

Advertisement

The similarities between the painting (1872) and the novel, Une Page d’Amour (1878), are striking: in the painting, a woman dressed in black and a little girl look out over a vast Parisian panorama from a large balcony on the Rue Franklin, a quiet street in the bourgeois neighborhood of Passy where the Morisot family resided. In the novel, the heroine, Hélène, a young widow still dressed in mourning, lives in that same street with her daughter. The view of Paris, very similar to that of the painting, is an obsessive motif throughout the book. In different seasons, at different times of the day, but always from the same window, Hélène gazes raptly at the immense cityscape dominated by the dome of Les Invalides. Zola, who claimed that he’d translated the Impressionists into literature,6 thus produced five superb and quite different descriptions of Paris in different lighting. But like Berthe Morisot’s women, who were mostly depicted indoors, his protagonist is by no means modern. She never ventures out to explore the big city and lives, behind the window glass, an entirely private life.

And yet women’s lives were changing in this period: from now on they were free to rid themselves of the constraints of bustles and crinolines, if they chose; during the day, they could go out unaccompanied, spend hours in the new Parisian department stores, or even sit down all alone, on the terrace of a café, this being perhaps the clearest illustration of the new freedom they were accorded. It was not merely a surface change: in the 1880s, schooling became mandatory for girls and universities began to admit women. They could become doctors, professors, or lawyers. New laws made it easier for them to divorce.

Manet loved audacious women. He preferred them to be independent like Nina de Callias (Lady with Fans), who left her husband and attracted to her salon a diverse array of talents. He liked them to be gifted like his friends and fellow painters Eva Gonzalès (Eva Gonzalès at the Piano, by Alfred Stevens) and Berthe Morisot, whose portrait he painted eleven times, or even unclassifiable, like the pretty Méry Laurent, muse to Mallarmé and mistress of the American Thomas Evans, who was Napoléon III’s dentist (At the Milliner’s).

Still, I find that, of all the modern women he painted, the most deeply moving one remains anonymous. She is the subject of Woman Reading. Sitting on the terrace of a café, with a stein of beer in front of her, she holds an illustrated newspaper in her hands; she’s tastefully dressed, her tulle collar evidence of a certain personal flair, while her gloves are an infallible mark of bourgeois respectability. Neither provocative nor shy, she is clearly at her ease. Balzac would have been tempted to frame a whole novel around her. For a Parisian flaneur, she represented the Nouvelle Femme, an active and curious person who refused to let herself be confined to her parlor but who was certainly not drawn to tawdry escapades.

Equally modern is Mary Cassatt, depicted from behind by Degas in a room of the Louvre. She has a neat, unfettered allure, verging on the androgynous: in a word, she exudes independence. She is leaning not on the arm of a man, but on an umbrella that could easily be taken for a walking stick (Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery). Another of Degas’s women, the one on the right in the series of three figures in Portraits in a Frieze, is dressed in a fanciful, easy-going style. In her ill-fitting jacket with its oversized sleeves and her completely unpretentious hat you might well take her for a streetwalker if it weren’t that her dainty pink-hued umbrella and the book she carries make it clear that even the daughter of a respectable family has the right to put on the airs of a bluestocking or a bohemian. She looks very much like a hippie before her time.

Tissot presents yet another view of the modern woman, at once elegant, soignée, and entirely original, in his Portrait of Mademoiselle L.L. As usual for him, Tissot paints with great precision, as detailed as anything by Ingres, and yet his model was oddly far from conventional. Mademoiselle L.L. is perched on the corner of a table covered with books and papers. On a chair sits a portfolio of sketches. A small vase with a bouquet of violets softens a studious atmosphere. This young person has dispensed with the crinoline, and has chosen instead a red bolero jacket that matches the ribbon in her hair, a red so red that it is shocking. It is impossible to assign to this powerfully attractive young woman a profession or a social standing. It is the curious amalgam of this ambiguity and the freedom of her level and slightly provocative gaze that makes her so modern.

Last of all, the final and essential element of this period’s modernity, recognized then and there by the Impressionists, was the transformation of Paris as it was demolished and rebuilt by Baron Haussmann. A modern city crisscrossed by broad boulevards rose from the rubble of the capital’s medieval heart. New neighborhoods took shape, in particular the Quartier de l’Europe surrounding the Gare Saint-Lazare, the most important train station in the Paris of that time. Caillebotte lived not far away. He therefore witnessed the construction of the immense metal viaduct that crossed all the station’s tracks and exemplified the miraculous power of the Industrial Revolution. The huge X-shapes of the bridge’s massive iron trusses fill the foreground of his Pont de l’Europe. With the Haussmannian buildings visible in the distance, Caillebotte’s canvas is a snapshot of the new city where the bourgeois brushes past the artisan without noticing his existence.

This is not a tableau of Parisian charm, such as Jean Béraud’s delightful depictions of a crowd leaving church after Mass (The Church of Saint-Philippe-du-Roule) or strollers crossing the Pont des Arts (A Windy Day on the Pont des Arts), any more than was Caillebotte’s wonderful Paris Street; Rainy Day. Set in the middle of the wall in the last room in the exhibition, this monumental painting (more than seven feet by nine), seems a fitting conclusion to the exhibition as a whole, one that encapsulates its importance.

Here we have not fashion but the city in the foreground, an austere city beneath gray skies, a new city with clean, straight, uncluttered streets, long lines of identical buildings, properly dressed pedestrians, indifferent to each other’s existence, isolated under the umbrellas that serve as their portable cocoons. The couple walking toward us hardly gives off a feeling of warmth and intimacy. The gentleman about to pass them lacks the basic courtesy to get out of the way: the two umbrellas are about to collide. Thus, the exhibition concludes with a gloomier, sadder vision of the city and its inhabitants, quite different from that of the painters seen in the earlier galleries. And yet it fits well with the aspect that is most deeply interesting: capturing the fleeting moment in which an artist depicts on canvas his contemporaries exactly as they are, with their clothing, their gestures, their way of life, and their “modernity.”

—Translated from the French by Antony Shugaar

-

1

Emile Zola, Écrits sur l’art (Paris: Gallimard, 1991), p. 357. ↩

-

2

Adolphe Tabarant, Manet et ses oeuvres (Paris: Gallimard, 1947), p. 341; quoted by Beth Archer Brombert, Édouard Manet: Rebel in a Frock Coat, (Little, Brown, 1996), p. 394. ↩

-

3

Charles Baudelaire, “Le Peintre de la vie moderne,” in Oeuvres complètes (Paris: Gallimard, 1976), Vol. 2, p. 687. ↩

-

4

Charles Baudelaire, “Théophile Gautier,” in Oeuvres complètes, Vol. 2, p. 120. ↩

-

5

The Hamburger Kunsthalle decided that the painting could not be flown to New York. It was shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art at the Manet retrospective in 1987. ↩

-

6

“I not only supported the Impressionists, I translated them into literature,” interview quoted in Henri Hertz, “Émile Zola, témoin de la vérité,” in Europe, No. 30 (November–December 1952), cited in William J. Berg, The Visual Novel: Émile Zola and the Art of His Times (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992), p. 9. ↩