The only surprising thing about the Museum of Modern Art’s announcement in April that it intends to demolish Tod Williams and Billie Tsien’s American Folk Art Museum of 1997–2001—an architectural gem that abuts the Modern’s campus on Manhattan’s West 53rd Street—to make way for yet another MoMA addition is that this deplorable decision took so long to occur. When in 2011 the Folk Art Museum was compelled to sell its decade-old building because of the worldwide economic crash that had caused its default on $32 million in bonds that financed the $18.4 million scheme, seasoned observers fully expected that the superb structure’s days were numbered.

Some commentators unfairly portrayed this debacle as the comeuppance of a quirky little institution’s overweening ambition. At a time when all cultural and educational institutions faced similar difficulties, MoMA’s own $425 million expansion scheme designed by Yoshio Taniguchi did not founder thanks to the emergency measures resorted to by some of its more deep-pocketed supporters. One venerable trustee is said to have anted up what he had expected would be a posthumous bequest.

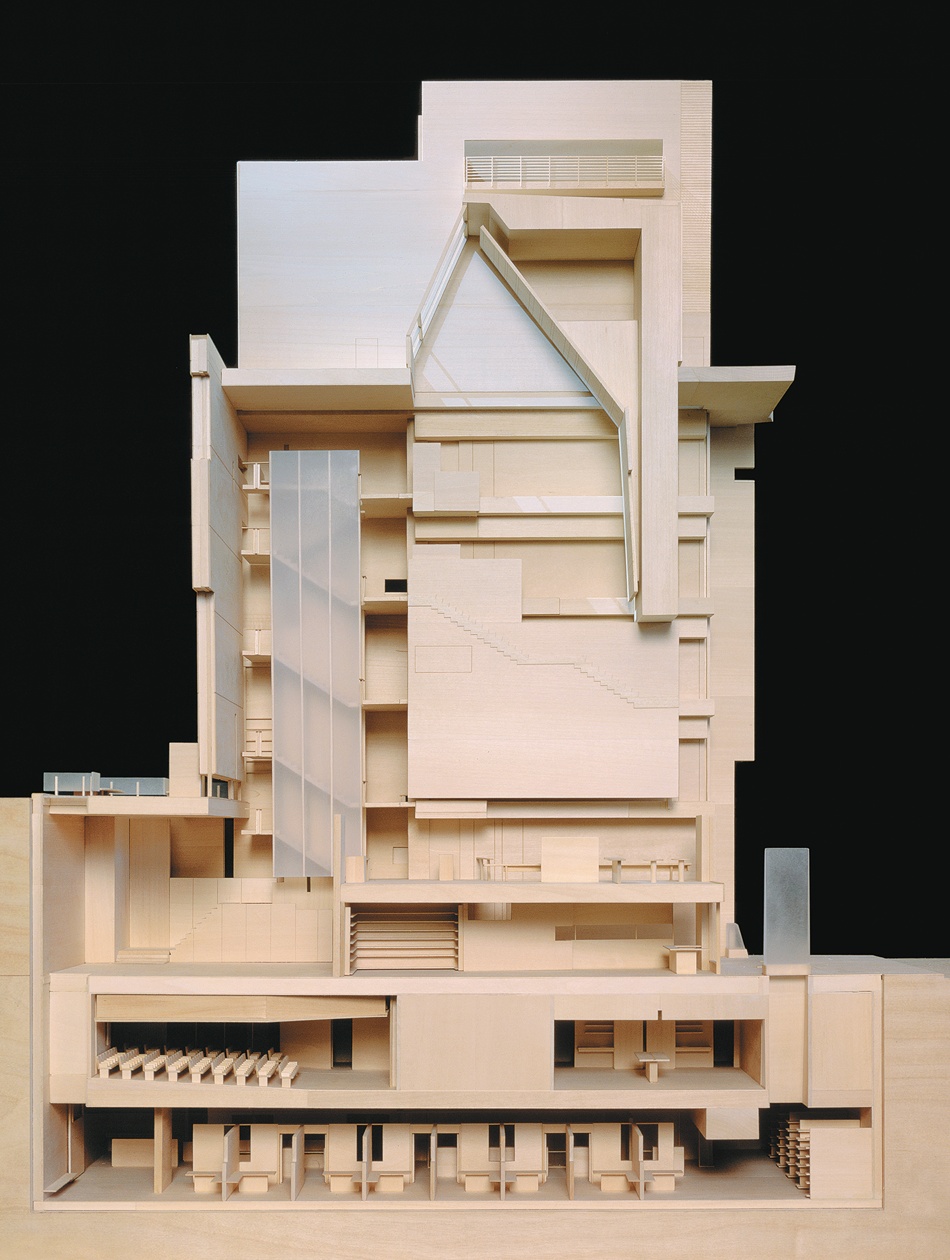

Williams and Tsien’s physically small (a mere forty feet wide and eighty-five feet high) but architecturally powerful incursion into MoMA’s presumed turf has long been known to be a thorn in the side of Glenn D. Lowry, the Modern’s director since 1995. Years before Lowry’s tenure and the Drang nach Westen he is so closely associated with, the Modern’s endlessly munificent benefactor Blanchette Rockefeller had deeded two narrow townhouses further down West 53rd Street to the fledgling Museum of American Folk Art (as it was then called). She never could have imagined how keenly MoMA would come to rue her well-intentioned gift.

As both museums began to finalize their grand construction plans in the mid-1990s, MoMA offered to swap the Folk Art plot for an equivalent area that it owned somewhat further west, a deal that would have given the Modern uninterrupted adjacency. But because the Folk Art site is aligned with a mid-block pedestrian mall that links 53rd Street with 52nd Street to the south—a configuration that Folk Art Museum officials felt made their institution look more important—they ill-advisedly rejected the trade, which likely heightened MoMA’s seemingly insatiable territorial imperative in the long run.

Lowry, after all, had been hired to serve as a sort of wartime consigliere for the Modern’s expansion initiative because, as the museum’s longtime head, the mild-mannered Richard Oldenburg, confided to several trustees, he did not want to take on that daunting campaign. Even before his arrival in Midtown Manhattan, Lowry was known as a museum executive who brooked no opposition. As director of the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto from 1990 to 1995, he laid off nearly half of that museum’s staff when the institution’s state-financed budget was cut by more than one third during a $58 million expansion scheme (though many employees were subsequently rehired). His reputation for toughness, doubtless a plus to his current employers, has not diminished in New York.

During a strike by MoMA employees in the spring of 2000, I walked along West 53rd Street on my way to a lunch date and was startled to come across Lowry confronting picketers on the sidewalk in front of the museum with flailing gestures. (That extraordinary sighting was confirmed by an article in The New York Observer.*) One could only think, “What would Philippe de Montebello do?” Soon thereafter, the troubling departure of two of MoMA’s most admired figures—the late Kirk Varnedoe, chief curator of painting and sculpture (who, his widow says, felt that his position was being eroded, and left in 2001, terminally ill with cancer, two years before his death), and Robert Storr, senior curator in that department (who has been dean of the Yale School of Art since 2006)—led to widespread questioning in professional art circles of Lowry’s management style.

Although, in a statement to The New York Review, the museum said that Varnedoe was not asked to leave, Varnedoe’s widow, the artist Elyn Zimmerman, told me that she believes that “the MoMA administration wanted Kirk to leave because his authority was threatening to Glenn.” Then, when Lowry wasn’t asked to participate in the elaborate memorial service for Varnedoe, underwritten by a group of MoMA trustees but held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he invited the recently bereaved Zimmerman for drinks at the Century Association, where she says he told her, “I know you didn’t want me to speak, but you don’t want to have me for an enemy.”

According to Storr, in a statement to The New York Review:

Glenn was jealous of Kirk in every way possible. Instead of letting his curators do their job, he micromanaged and interfered in areas far outside his expertise, and thereby blew whatever chance he ever had to be a great director on the order of Alfred Barr. It was the Peter Principle at work with a vengeance. Plus there was, as Kirk described it to me in detail, an appalling level of cruelty in doing what he did to a man who was living on borrowed time, to make a man’s final years hellish for the sake of self-aggrandizement and the sheer pleasure of corporate intrigue.

The New York Times story on Lowry and his trustees’ decision to destroy the Folk Art building reported that “MoMA officials said the building’s design did not fit their plans because the opaque façade is not in keeping with the glass aesthetic of the rest of the museum.” But as Ned Cramer wrote in an Architect magazine article titled “The Day That MoMA Died,” “It’s as though the board voted to incinerate a Gerhard Richter painting because it didn’t match the floor tile or fit through the doorway.”

Advertisement

The idea that Williams and Tsien’s structure has to go because its striking, nearly windowless façade does not blend in with MoMA’s banal 53rd Street elevations is simply preposterous. The notion of a standardized street front seems especially egregious when advanced by an institution putatively dedicated to championing modern architecture and design in all their untidy diversity. And what about the long stretches of black granite paneling that give the West 54th Street elevations of Taniguchi’s addition a mute aspect far more forbidding than the slender vertical thrust of Williams and Tsien’s richly textured white-bronze-alloy frontispiece? Rare among works of contemporary architecture, the Folk Art Museum’s majestic front responds subtly to changing weather and light conditions during the day and looks especially beautiful when illuminated at night.

MoMA’s unconvincing rationale also contradicts its own building history. The preservation of the façades of the museum’s earlier incarnations on the block—including Edward Durell Stone and Philip S. Goodwin’s original International Style building of 1937–1939 and Philip Johnson’s east wing of 1964—was mandated as part of the latest expansion scheme, to maintain visible links with the museum’s past and to incorporate evolving approaches to modern building design. Apparently MoMA wants the public to believe that because the former Folk Art building was not a MoMA-sanctioned creation to begin with, it is unworthy of the same deference accorded its nearby (and less architecturally distinguished) neighbors.

Remarkably, even as MoMA’s leadership revealed its scheme to destroy the Williams and Tsien building, the museum claimed that it had not yet chosen an architect to design a replacement, or decided exactly how the new spaces would be used, or set a budget, or even commenced fund-raising. (Still more dispiriting is the museum’s expressed intention to fill the street-level space of the former Folk Art site with more shopping venues or perhaps another restaurant. As if MoMA—whose display galleries now sometimes reek of fugitive cooking odors from its multiple food-service facilities and whose retail operation resembles a major department store—were not already overloaded with such money-spinning ventures.)

This vagueness of purpose was underscored by an astounding comment from Lowry, who insisted to a Times reporter that the demolition is “not a comment on the quality of the building or Tod and Billie’s architecture.” Even taking Lowry’s dubious protestation at face value, we do know that the architects were not asked to adapt their Folk Art gallery to MoMA’s new purposes. This is a possibility that might well have been pursued—and still should be pursued—on the basis of Williams and Tsien’s recognized stature among the finest museum architects of our time. One need only consider their intelligent Phoenix Art Museum expansion of 1991–2006 and widely acclaimed Barnes Foundation gallery of 2004–2012 in Philadelphia—or the decision by MoMA itself to invite them to participate in the 1997 competition for the comprehensive expansion scheme won by Taniguchi. At the very least, they certainly could have ideas worth considering, and serious attempts should be made to save and adapt their building.

Another central player in this drama has been the New York real estate developer Jerry Speyer, chairman of MoMA’s board of trustees since 2007 (and who, as it happens, lives in an imposing townhouse on Manhattan’s East 79th Street designed for him by Williams and Tsien). Speyer was head of the building committee that oversaw the Taniguchi expansion, during which, as I was told by two technical consultants who worked on the project but have asked not to be identified, he encouraged economies that saved the museum a fortune.

Advertisement

As a result, when I took Taniguchi to lunch at the Grill Room of the Four Seasons restaurant on the day of a press preview for the new building in 2004, he told me he was less than happy with detailing and finishes and that he felt these diminished the perfectionism for which he is renowned in Japan. (MoMA’s then deputy director for marketing and communications, Ruth Kaplan, though uninvited by me, followed us from the museum and tried unsuccessfully to intervene in our conversation.)

The unconscionable decision to destroy the work of Williams and Tsien seems especially ironic in light of the museum’s revivified department of architecture and design. MoMA’s chief curator of architecture and design since 2007, the Columbia architectural historian Barry Bergdoll, has organized important exhibitions on social and environmental issues, impeccable scholarly retrospectives, and even a hugely popular reprise of the Houses in the Museum Garden series of 1949–1955.

Bergdoll had remained silent until the controversy grew into something of a public relations disaster for the museum as protests mounted. (On April 22, the venerable Architectural League of New York issued an open letter asserting that MoMA “has not yet offered a compelling justification for the cultural and environmental waste of destroying this much-admired, highly distinctive twelve-year-old building.”) A week after the demolition plan was revealed Bergdoll finally commented to the press. According to an article in The Architect’s Newspaper, he said

that the decision was an administrative, rather than a curatorial one. He called the decision “painful” for architects and others who appreciate Williams and Tsien’s work, and acknowledged that museums have a responsibility to the art in their care—including architecture. But, he said, the building “was designed as a jewel box for folk art,” and could not reasonably be altered to fit a different collection and a different purpose.

But why could a “jewel box for folk art” not become a jewel box for architecture and design, or another purpose, by some use of the imagination? Perhaps displays of large-scale objects might not fit into the Williams and Tsien galleries, but MoMA’s permanent design collection—for the most part domestic-scaled objects displayed in vitrines—and the department’s frequent shows of architectural drawings could easily be accommodated there. MoMA says it would gain 10,000 square feet of exhibition space from the Folk Art Museum site. According to Williams and Tsien’s calculations, their 14,000-square-foot building contains 7,000 square feet of usable display space. Could its destruction possibly be justified by a net gain of a mere 3,000 square feet, roughly the size of a roomy Manhattan apartment?

In view of what is widely known in the art community about power dynamics within MoMA, it surely would be career suicide for Bergdoll to openly contradict his boss over this matter. The architecture and design curator’s canny statement—in which he clearly if tacitly distances himself from Lowry’s decision—also runs counter to Bergdoll’s stated positions on adaptive reuse of buildings and the need to sustain them, the subjects of two recent, well-received shows of his at the museum.

As Williams and Tsien have confirmed, they were never approached for suggestions about how that might be done—and who better to ask than those who designed the structure? In a statement for The New York Review, Williams and Tsien wrote that they

believe the sixth-floor Folk Art gallery nearly aligns with one of MoMA’s main gallery floors. It remains our hope that MoMA might find a way to successfully adapt the building as part of their campus.

To be sure, it might take more ingenuity to mount architecture or design exhibitions in the Williams and Tsien building—the most logical reuse for it, as proposed by a number of commentators—than in the blandly generic expanses of the recently revamped MoMA behemoth. But the same complaint used to be directed at both Frank Lloyd Wright’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum of American Art (each admittedly larger than the Folk Art Museum) until sympathetic curators demonstrated how exceptional architecture can enhance our experience of equally exceptional art.

The most basic task of any museum must be the protection of works of cultural significance entrusted to its care for the edification and pleasure of future generations. This imperative rightfully takes precedence over acquisition, interpretation, outreach, or any number of other activities now believed to be crucial to the survival of our great art repositories. Sometimes a museum gains its holdings with much strategic forethought, and at other times serendipitously, as when a long-coveted neighbor’s plot suddenly becomes available. Yet the moral responsibility remains the same.

The tragic turn of events on West 53rd Street is nothing less than impending cultural vandalism, made more odious because it will be carried out by a presumed institutional guardian of high culture and contemporary design. As MoMA grows and grows and builds and builds, the destruction of this architectural landmark will not be an irreversible decision until the first sickening thwack of the wrecker’s ball.

The museum says the building will be gone by the end of this year, but there is still ample time for MoMA officials to fully reconsider what this concerted outcry should warn them of: a mistake of epic proportions. If they proceed as promised, their actions may someday be forgotten by the general public; but for those who care about the long view of culture, this needless desecration of an important example of the building art by two of today’s most highly respected architects will remain a permanent blot on the reputation of those responsible for it. Let us hope they change their minds.

—April 25, 2013

This Issue

May 23, 2013

An Original Thinker

Maggie

-

*

See Andrew Goldman, “Hey! What’s the Big Deal at MoMA?” The New York Observer, June 5, 2000. ↩