When a woman from the Cabinet Office at Number 10 Downing Street, the residence and offices of the British prime minister, told me over the phone that I was invited to the funeral of Margaret Thatcher, I immediately suspected it was a scam. I get regular calls intended to extract money from me. I said I would call her back, looked up the Cabinet Office phone number, and when I called, the same woman answered. “Why me?” I asked. “I was nothing to Lady Thatcher.” She told me I was “on the list,” and that she would send me an invitation by courier.

Why me? I had never been a parliamentary journalist. My career was as a foreign correspondent in China and Hong Kong. Margaret Thatcher’s visits to China were brief and unsatisfactory. But I did have a little history with Mrs. Thatcher, including four personal encounters. Here’s how they happened.

As leader of the opposition, Mrs. Thatcher had gone to China in 1977 and hadn’t liked it. In 1982, now prime minister, she went again to Beijing to negotiate the handover to China of British-ruled Hong Kong, stipulated by a nineteenth-century colonial treaty to occur in 1997. For three days she argued with Premier Zhao Ziyang and Senior Leader Deng Xiaoping for some sort of special arrangement that would not include the colony under direct mainland rule, but was forced to agree to what actually occurred, namely that Hong Kong would return to China on July 1, 1997, although Deng agreed that Beijing would not interfere with Hong Kong’s internal arrangements for fifty years.

My own meetings with Mrs. Thatcher took place after that agreement. In early June 1989, I returned to London from Beijing, where I been a correspondent for The Observer. The Armed Police in Tiananmen Square had assaulted me on the night of June 3, knocked out five teeth, fractured my left arm, and beaten me black and blue. A few days later I found myself at a reception of some sort where, unknown to me, the prime minister was also present. I was led up to her and introduced. She told me she had been reading my dispatches and asked if “we,” her preferred pronoun for herself, could do anything for me, did I have a good doctor, and to let her know if there was anything I needed. We shook hands. One minute.

In 1997, not long before the handover to which she had reluctantly agreed, Lady Thatcher, as she now was, came to Hong Kong to deliver a highly paid speech to the Chinese and British Chambers of Commerce. I was now East Asia editor of The Times of London. The day before her speech she asked to walk about central Hong Kong, accompanied by local and foreign reporters. Suddenly she declared, “I must buy some socks for Denis,” her husband, who was in London. A nearby Marks & Spencer was cleared and police stood in the doorway. I trotted to the unguarded back door and inside saw Lady Thatcher at the sock counter with a young saleswoman. She was just saying she had forgotten her money. I paid for the socks; she took the bag, didn’t thank me, and went outside. I left by the back door. Another minute.

That night, Chris Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong, a Tory MP, and one of those who, during her third term, deposed Prime Minister Thatcher, gave a dinner party for her to which my wife and I were invited. After the meal, Lady Thatcher sat on a couch; guests were led up to it, chatted for a few minutes, and then made way for another guest. Near midnight I was on the couch, telling Lady Thatcher that when she gave her speech the next day she must mention that many international business deals with China were concluded across the border in Hong Kong, where there was (and is) a rule of law. I said it would be important to underline that difference with mainland China. She said she didn’t know that international contracts on the mainland were routinely signed in Hong Kong, but no, no, no, the speech was already written.

After half an hour still on the couch she looked over at the heavy-eyed Patten and the few remaining guests and asked what he thought. He said, “It would be insane to get between Margaret Thatcher and Jonathan Mirsky.” Finally, she agreed to include what I suggested in her speech: she would emphasize that contracts had legal force in Hong Kong that they did not have on the mainland. At least it would be clear that Hong Kong had a rule of law lacking in the China controlled by Beijing. As my wife and I left Government House, her speechwriter came up behind us and whispered, “Fuck you, I’ll have to spend the rest of the night rewriting the speech.” About an hour.

Advertisement

The next night I waited outside the banqueting hall where Lady Thatcher was to give her speech. I would be admitted to the hall after the meal. When it ended the doors flew open and guests rushed to the toilets. There was a long queue outside the ladies’. Mrs. Thatcher bustled over and exclaimed, “I must get back into the hall for my speech.” I told her to wait right there, went into the gents’, where there were ten or so men; I asked them to leave because Lady Thatcher needed to come in. Zipping up, they left. “Go ahead in,” I said to Lady Thatcher. “I’ll stand at the door.” She went in, after a minute or two came out, didn’t thank me, went back into the hall, and gave her speech with my suggestion included. Two minutes.

The funeral at St. Paul’s Cathedral was one of those events that, as they say here, “The British do damn well.” The cathedral was stuffed, as they also say here, with “the great and the good.” I recognized one or two of both, including ex-Governor Patten. The coffin was carried to the cathedral door on a hundred-year-old gun carriage drawn by matched, perfectly behaved black horses and escorted by Brigade of Guards officers wearing their bearskin headpieces, on similarly matched chargers. Eight representatives of the services carried the coffin in perfect step into St. Paul’s. The Queen, very small, and Prince Philip, with a drop on the end of his nose, were escorted in, preceded by the Lord Mayor carrying the black Mourning Sword. The Bishop of London, the Right Reverend and Right Honourable Richard Chartres, KCVO (Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order), gave a kind of eulogy in which he recalled sitting next to Prime Minister Thatcher at a banquet: “She gripped my arm and said, ‘Don’t touch the duck pâté, Bishop. It’s terribly fattening.’”

I sat next to a general who long ago, during the Troubles, commanded the army in Northern Ireland and slept every night with a pistol under his pillow. Behind me was a Guards colonel in a scarlet tunic hung with medals and carrying a funeral “short sword.” He said to his neighbor, “By God, as I was walking over here a pretty girl said to me, ‘Wow, you’d make a great accessory to me in Chanel.’” As I said, what was I doing there?

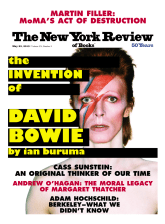

This Issue

May 23, 2013

MoMA’s Act of Destruction

An Original Thinker

Maggie