Turning the life and times of Imelda Marcos into a piece of musical theater set in a disco is almost too obvious. She was, after all, a disco queen herself, dancing the nights away under mirror balls installed in her various palaces and town houses, with her entourage of louche international socialites and B-movie actors who often looked like George Hamilton, including George Hamilton himself. The problem with the idea is that nothing on stage can ever be quite as zany as the Filipino first lady’s real life.

And yet the musician David Byrne’s imagining of Imelda’s inner landscape mostly works very well. Byrne is a pop polymath, a composer of film music as well as an author. In his latest book, How Music Works, he gives fascinating descriptions of his many collaborations with other musicians, such as Brian Eno, in which they exchange ideas and even record music on their laptops.* The idea to write a disco opera, in collaboration with DJ Fatboy Slim, began in 2005. Byrne writes: “Reading that Imelda had said she wanted the words HERE LIES LOVE inscribed on her tombstone was like being handed the title of the musical on a platter.”

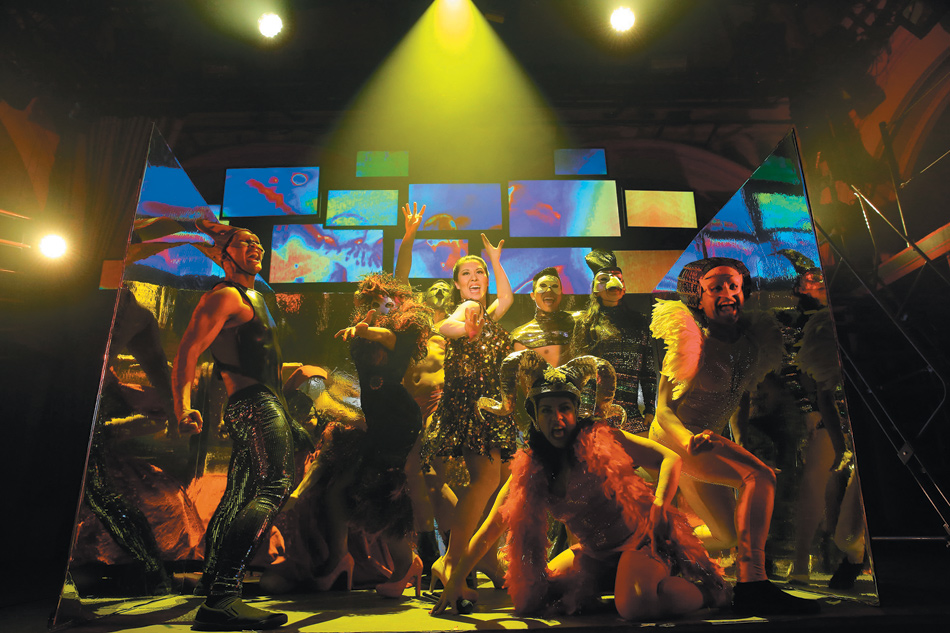

The pop opera, brilliantly staged by Alex Timbers and choreographed by Annie-B Parson, is performed in a made-up disco with constantly shifting stages sliding across the floor. As video clips are flashed onto the walls, in a kind of light show of Imelda’s public life, the mostly middle-aged audience at the Public Theater is coaxed by a raucous DJ and pink-suited ushers into bopping along with the actors. (Most people appeared to be more than willing to wave their arms and whoop and holler. I’m in the minority that tends to resist this kind of festive bullying by becoming stony-faced and rigid.)

Filipinos have a word, palabas, meaning show or farce. Much in the Philippines is palabas, including, alas, much of its politics. The Marcos dictatorship (1965–1986), corrupt, kleptomaniacal, and sometimes brutal, was full of palabas. Power was gilded with show—grandiose speeches, carnivalesque campaigns, huge artistic projects, endless pageantry, and absurdly extravagant parties. Ferdinand Marcos himself was a ruthless operator more than a showman. He went for the power. His wife provided much of the palabas.

The first half of Byrne’s musical, full of kinetic dance numbers, shows Imelda’s rise from her childhood as a poor relation of a wealthy provincial family. Her first step to glory is to become a famous beauty queen. She won several contests in the early 1950s. (In one instance, according to Time, after she lost a Miss Manila contest, she complained so bitterly to the mayor of the town that he gave her the title “the Muse of Manila.”)

In the musical, Imelda, very well sung by the mellifluous Ruthie Ann Miles, is shown as a somewhat naive young woman, sugary, mawkish, obsessed with love and beauty—the tinselly fantasies of a fiesta queen. The story that follows is a variation of The Rake’s Progress: her sentiments are corrupted by increasing power and wealth; delusion ends up bringing her down.

This is where the pop songs fit perfectly, from the poignant “The Rose of Tacloban” to the more steely “Walk Like a Woman.” Love and ambition become hopelessly entangled once she marries Marcos. The provincial beauty queen becomes a power-hungry pseudo-monarch, expecting her people to love her shows of wild lavishness, her shopping sprees, her clothes, her dances with presidents and dictators, her gigantic cultural center in Manila, as much as she does—and in fact many of them do, in the way poor people often take vicarious pleasure in the abundance of their kings and queens. The musical gives her shenanigans a kind of tawdry allure, which some people have criticized, but which seems right to me. It was precisely the pop glamour of the Marcos dictatorship that made it so insidious.

Less interesting, even though he has some of the best songs in the show, is the character of Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., Ferdinand Marcos’s old fraternity brother and main political rival, and, moreover, one of Imelda’s first boyfriends. His is the voice of conscience. Ninoy is the noble prince in this political fairy tale who stands up to the forces of darkness.

As the audience keeps bopping, Ninoy is seen making fine-sounding speeches, being jailed, and finally, in a climactic scene, getting assassinated on the tarmac of the Manila airport. In real life, his killing, which occurred upon his return from exile in 1983, was the beginning of another type of palabas: massive street demonstrations in Manila with drummers and dancers and sentimental patriotic pop songs played by the guitar-strumming star of the day, Freddie Aguilar. One of the slogans, ubiquitous on the sea of yellow T-shirts, was: “A Filipino is worth dying for.”

Advertisement

This side of the People Power story gets less attention than it merits, perhaps, especially in a musical about political theater. Ninoy Aquino, in life a less saintly figure than he appears in the show, was the catalyst for a cult that would revolve around his wife, Corazon “Cory” Aquino, which was almost as wacky as Imelda’s delusional circus. But Cory’s brand of palabas was religious. A modest housewife for most her life, Cory, who became president following the uprising against Marcos in 1986, was the saint of People Power, and claimed to have nightly conversations with Ninoy in heaven. Her newly acquired charisma, backed by the Catholic Church, was one of the factors that brought the Marcos autocracy down.

More could have been made of this. Instead, the demise of Imelda, the Rose of Tacloban, seems a bit rushed. After an excellent swan song by Imelda to the people who rejected her, “Why Don’t You Love Me?,” we hear the noise of the helicopter that lifted the disgraced couple from their palace in Manila. We are left with a ballad, sung by the DJ, entitled “God Draws Straight,” about people coming together to banish the evil ones—a fairy-tale ending that is almost as sentimental as Imelda’s paeans to love and beauty.

The real sadness of the Philippines is that the carnival of Saint Cory did so little to improve the lives of most Filipinos. Power remains in the hands of a few immensely rich landowning families, including the Aquinos themselves. The current president is Aquino’s son—not a dictator, to be sure, which is at least something. Imelda, now in her eighties, is back home, running for a seat in the Filipino House of Representatives, her stolen wealth intact. Her daughter is governor of Ferdinand Marcos’s native province. And the majority of the population is still much poorer than it ought to be. The palabas just goes on, and on, and on.

I reflected on this as we left the disco stage at the Public Theater, the audience still happily jigging along with the music, feeling good about what they had seen. And I thought of the only time I met Marcos and Imelda, for lunch at their house in Hawaii, where they lived after they were ousted. Imelda was talking about Ninoy Aquino. “You know,” she said about the man for whose violent death she might have been partly responsible, “he was all sauce and no substance.” Marcos: “But honey, that is the essence of Filipino politics!”

This Issue

June 20, 2013

What Is a Warhol?

Cool, Yet Warm

Facing the Real Gun Problem

-

*

McSweeney’s, 2012. ↩