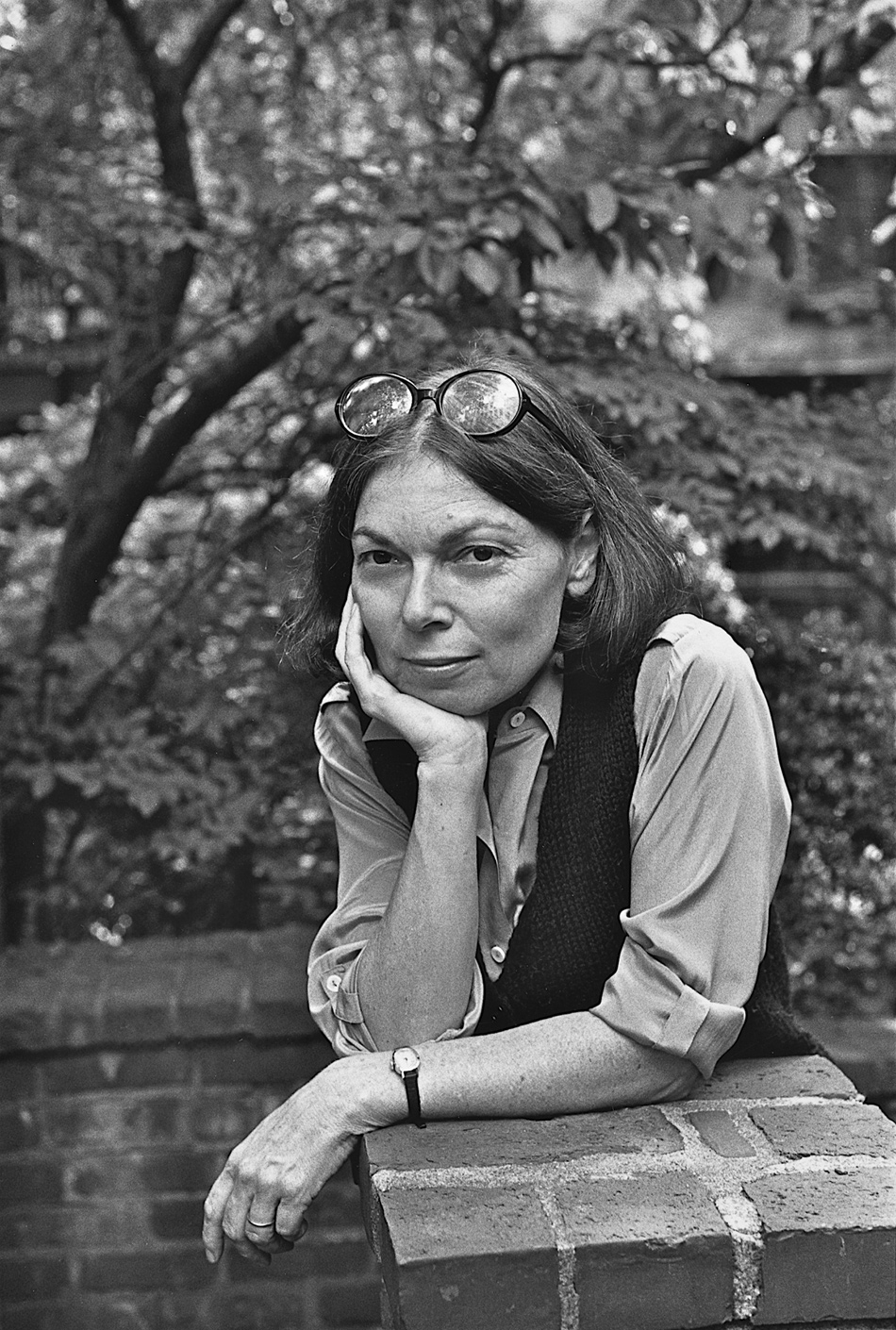

In “Good Pictures,” an essay about Diane Arbus in Forty-One False Starts, Janet Malcolm’s latest collection, we witness a wonderful outburst of Malcolmian irritation. The prompt is Revelations, a giant volume of Arbus’s photographs, published to coincide with a retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Malcolm is appalled by the book. She believes it contains too many inferior photographs and too much text. Worst of all, she writes, it mingles text and photographs in such a way that there is no peaceful space in which to contemplate the photographs by themselves. Her indictment of the book’s bloated contents, lousy design, and sloppy editing continues at some length, before reaching its climax in a furious flight of metaphor:

The book reminds me of a porch I know with a lovely view of a valley, but where no one ever sits, because it is crammed from floor to ceiling with mattresses, broken chairs, TV sets, piles of dishes, cat carriers, baby strollers, farm implements, unfinished woodworking projects, cartons of back issues of Popular Mechanics, black plastic bags filled with who knows what.

Mess has always inspired fervent emotions in Janet Malcolm. It agitates her. It depresses her. She considers it her enemy. The job of a writer, she likes to remind us, is to vanquish mess—to wade onto the seething porch of actuality, pick out a few elements with which to make a story, and consign the rest to the garbage dump. Images of clutter and panic-inducing domestic chaos crop up frequently in her work, not just as metaphors for the failure or absence of art, but as advertisements for her own narrative discipline. This is what real life looks like, they tell us. This is the tedium and confusion that Malcolm’s elegant rendering of things has spared you.

But if literal messes appall Malcolm, they also fascinate and attract her. Notice how in the course of describing the porch in the Arbus essay, she starts to become interested in the junk it contains. Her official position is that everything here must go, but the mess waylays her, draws her in, until she seems perilously close to crouching down and starting to flip through back copies of Popular Mechanics. In The Silent Woman, her book about Sylvia Plath, a visit to the terrible, Collyer-like house of Plath’s former neighbor Trevor Thomas elicits horror—but also a wistful sort of admiration:

Before the magisterial mess of Trevor Thomas’s house, the orderly houses that most of us live in seem meagre and lifeless—as, in the same way, the narratives called biographies pale and shrink in the face of the disorderly actuality that is a life.

Malcolm has a secret, writerly sympathy for the hoarder. She understands the mad desire to hold on to every piece of accumulated material, the fear of throwing out something precious. Art, she is fretfully aware, can be too ruthless in its cleaning operations. This is the peril she is slyly gesturing at in “A Girl of the Zeitgeist,” another essay in this collection, when she describes the austerely stylish living room of the art critic Rosalind Krauss:

Each piece of furniture and every object of use or decoration has evidently had to pass a severe test before being admitted into this disdainfully interesting room…. Perhaps even stronger than the room’s aura of commanding originality is its sense of absences, its evocation of all the things that have been excluded, have been found wanting, have failed to capture the interest of Rosalind Krauss—which are most of the things in the world, the things of “good taste” and fashion and consumerism, the things we see in stores and in one another’s houses.

There is something awe-inspiring and at the same time a little barren about an environment from which all trace of “disorderly actuality” has been removed.

The tension between the messiness of truth and the false tidiness of art is Malcolm’s great subject. A fretful awareness of what is lost, overlooked, and distorted in the process of transforming reality into narrative finds its way into everything she writes. She imposes narrative order on all kinds of messes—the tribal politics of the contemporary art world, the internecine squabbles of the psychoanalytical establishment, the dysfunctional and sometimes destructive bureaucracy of the New York State family justice system—but never lets us forget the process by which that order has been achieved. She is constantly reminding us that her beautiful, lucid texts are stories, shaped by a writer with certain aesthetic and professional imperatives, certain vanities and prejudices and idiosyncracies of her own.

The parts of her self-reflexive commentary that have garnered the most attention over the years (in part, no doubt, because they reinforce a popular animus toward journalists) are those that address the duplicity of the journalistic enterprise. Malcolm’s observations about the fundamental sneakiness of a reporter’s work—the “moral anarchy” that enables reporters to place “a text’s necessities” above “a person’s feelings”—are justly famous. But the attention they have received has had a tendency to overshadow everything else in her work. (The first sentence of The Journalist and the Murderer—about journalism being “morally indefensible”—is endlessly quoted; her other, no less crucial remark, from the same book, about the writer’s necessary “identification with and affection for the subject” is not so well remembered.)

Advertisement

As a result, her work is sometimes spoken of as if its principal, or only, contribution to our understanding of the hazards of nonfiction writing was to have revealed that journalists are rats. And this distortion of what she has written about journalism has encouraged a distorted perception of her journalism itself. The asperity of her profiles is grossly exaggerated. She is widely understood to be a writer of preternatural toughness—a person who “discovered her vocation in not-niceness.”1

In fact, as the essays in this collection remind us, Malcolm’s characteristic style is a complicated blend of beady-eyed coolness and romantic warmth. If she is sometimes disapproving and tart, she is also often affectionate, empathetic, even swooningly tender. Which is to say, she falls in love with her subjects quite as often as she takes against them.2

Consider “A Girl of the Zeitgeist,” in which Malcolm profiles Ingrid Sischy, the recently appointed editor of Artforum. The character of “wild and assertive contemporaneity” that the magazine has acquired under Sischy’s editorship has led Malcolm to expect certain qualities from her protagonist. She has imagined—hoped—that she will encounter “some sort of strikingly modern type, some astonishing new female sensibility loosed in the world.” (For which a cynical reader might read, she has been looking forward to satirizing Sischy.) Instead, she has found “a pleasant, intelligent, unassuming, responsible, ethical young woman” devoid of “theatrical qualities.” Sischy, to use one of Malcolm’s coinages from The Journalist and the Murderer, is a person who does not “auto-fictionalize.” She has no aggrandizing instinct for turning herself into a colorful “character.”

Part of Malcolm’s answer to this dilemma is simply to keep Sischy offstage for much of the piece and to concentrate her attention on the circus-like group of critics and artists around Sischy. Her other, rather ingenious solution is to address the fact of Sischy’s colorlessness head-on and to proclaim it as a virtue. One could argue that in this case, the “text’s necessities” encourage an excessively generous interpretation of the subject.

Toward the end of the profile, Malcolm makes the rather startling claim that Sischy’s “personal mutedness is the by-product of an Orwellian sense of cultural crisis.” In other words, her dullness is a conscious act of noble self-abnegation:

The heroes and heroines of our time are the quiet, serious, obsessively hardworking people whose cumbersome abstentions from wrongdoing and sober avoidances of personal display have a seemliness that is like the wearing of drab colors to a funeral.

“A Girl of the Zeitgeist” is finally, then, a fable about the deceptiveness of appearances. Whether or not we are convinced by Malcolm’s heroic reading of Sischy’s muted person, the task she undertakes here—to reveal the moral beauty beneath her subject’s unexceptional surface—is very much in keeping with our conventional notions of what journalism is meant to do. We like to think of reporters revealing the truths beneath façades, trumpeting overlooked virtues, and so on. This, as it happens, is a satisfaction that Malcolm offers only rarely in such a straightforward form. Her more usual strategy is to complicate her own conclusions by questioning what it is possible for her, or anyone else, to finally “know” about other people.

The warning she issues in “A House of One’s Own,” her essay about Bloomsbury, is typical in this regard:

In what I have written, in separating my Austenian heroines and heroes from my Gogolian flat characters, I have, like every other biographer, conveniently forgotten that I am not writing a novel, and that it really isn’t for me to say who is good and who is bad, who is noble and who is faintly ridiculous. Life is infinitely less orderly and more bafflingly ambiguous than any novel…. We have to face the problem that every biographer faces and none can solve; namely that he is standing in quicksand as he writes. There is no floor under his enterprise, no basis for moral certainty.

In the essay, Malcolm considers two competing versions of history. On one hand there is the legend of Bloomsbury, wherein “a luminous group of advanced and free-spirited writers and artists” blow away the cobwebs of grim Victorian England and usher in the modern era; on the other is the baleful counternarrative of Angelica Bell, daughter of Vanessa, who has published a book, Deceived with Kindness, declaring that all was not so wonderful in her mother’s house at Charleston.

Advertisement

Malcolm argues that while Angelica’s book “introduces…the most jarring shift in perspective,” it fails to decisively disrupt the Bloomsbury legend. This is not because the primary Bloomsbury narrative is “truer” than Angelica’s account of family dysfunction and abuse, but because it is more rhetorically persuasive. Angelica’s shrill complaints lack the sprightly irony, the wily obliqueness of the classic Bloomsbury tone:

We withhold our sympathy [from Angelica] not because her grievance is without merit, but because her language is without force…. Angelica cloaks and muffles the complexity and legitimacy of her fury at her mother in the streamlined truisms of the age of mental health.

She concludes:

But Angelica’s cry, her hurt child’s protest, her disappointed woman’s bitterness will leave their trace, like a stain that won’t come out of a treasured Persian carpet and eventually becomes part of its beauty.

In the absence of moral certainty, Malcolm suggests, our sympathies are assigned on what are essentially aesthetic grounds—on the basis of who has the more attractive language, or the more engaging style. This is a rather shocking proposition and it is meant to be.

Another writer, recognizing the necessary and irreducible ambiguity of “what really happened,” might resist stating an allegiance. But that sort of mealy-mouthedness is not an option for Malcolm. “Fairmindedness” and “evenhandedness,” she famously observes in The Silent Woman, are only ever “rhetorical ruses.” The strong views that one conceives about the nature of the Hughes-Plath marriage, or about the family life of the Bells, may, as the critic Jacqueline Rose points out, be “false and damaging”—never quite equal to the complexity and infinite nuance of the reality of the case—but it is a “psychological impossibility,” Malcolm argues, for a writer not to arrive at such views. “Without some ‘false and damaging certainty,’” she observes, “no writing…is humanly possible.”

Malcolm’s habit of taking a side, while simultaneously pointing out the questionable grounds for doing so, is one of the most distinctive and controversial features of her writing. Some readers would prefer that she do one thing or the other. They find the combination of Solomonic judgment and candid epistemological skepticism too unsettling. Others are happy to accept Malcolm’s frankly novelizing approach when it is used to animate Bloomsbury quarrels, but are less comfortable when it is applied to murder trials.3 Still others find that her authority is enhanced by her acknowledgment of bias.

The title essay of this new collection is Malcolm’s unique experiment in telling a story without the ballast of an organizing point of view. In lieu of a conventional narrative profile of the artist David Salle, she offers up a series of “false starts” at a narrative. Each of her beginnings, with its slightly different emphasis, points to a subtly different conclusion, but none is pursued. Malcolm cannot “capture” Salle. His ambiguity and inconsistency resist novelization. The impressions and incidents and ideas accumulate, but fail to add up. “I feel,” she writes a little plaintively at one point, “that I can only almost know him.”

In order to accommodate this “almost knowing,” she finds herself borrowing Salle’s artistic strategies. “To write about the painter David Salle,” she explains, “is to be forced into a kind of parody of his melancholy art of fragments, quotations, absences—an art that refuses to be any one thing or to find any one thing more interesting, beautiful, or sobering than another.”

One might interpret this “parody” as a homage—the ultimate sign of Malcolm’s identification with and affection for her subject—but she leaves this possibility, like everything else in the piece, unconfirmed. Her affection for Salle comes and goes. She is aware of “benign, admiring feelings” during her interviews with him, but in his absence, these feelings curdle. “As I write about him now—I haven’t seen him for a month—I feel the return of antagonism, the sense of sourness.”

“Forty-One False Starts” is a remarkable and, in its strange way, gripping piece of work. It achieves the rare feat of communicating something valuable about the largely ineffable “creative process.” And while it never resolves itself into a decision about Salle, it does, like one of those scent-impregnated strips in a magazine ad, offer up a very strong and complicated whiff of him.

It is a sign, perhaps, of how well Malcolm’s work has trained us that while we admire the beauty and skill of this piece, we never fully accept its spirit of inconclusiveness. If Salle resists Malcolm’s efforts to give him the fixity and consistency of a literary character, we end up assigning him a mythical status anyway. He is Malcolm’s Difficult Subject, or the Man She Only Almost Knew. Or perhaps just the One That Got Away.

This Issue

June 20, 2013

What Is a Warhol?

Facing the Real Gun Problem

-

1

See Craig Seligman, “Janet Malcolm,” Salon, February 29, 2000. ↩

-

2

It is possible that Malcolm herself exaggerates the inquisitional froideur of her work. In a fragment entitled “Thoughts on Autobiography from an Abandoned Autobiography” that appears in this collection, she suggests that the “I” of journalism, “whose relationship to the subject more often than not resembles the relationship of a judge pronouncing sentence on a guilty defendant” is quite different from the more tender and forgiving “I” of the autobiographer who “tells the story of the observed ‘I’…as a mother might.” ↩

-

3

In his recent book, A Wilderness of Error, Errol Morris revisits the murder trial of Jeffrey MacDonald and suggests that when Malcolm wrote about the same case in The Journalist and the Murderer, she was too quick to conclude that the objective truth about the murders was unknowable from the available evidence and that any firm conclusions about the case came down to one’s “impressions of the defendant.” ↩