If an anthropologist from the star system Sirius were to teleport to earth to conduct a field study of Christianity, where would she go? A Greek monastery on Mount Athos, a papal mass in St. Peter’s, a convent hospital for the destitute in Calcutta, a snake-handling service in the Appalachians, a Quaker meeting? The figure of Jesus of Nazareth lies somewhere behind them all, but it would be hard to say exactly how, or what else they might be deemed to have in common. And if our extraterrestial anthropologist should decide to turn historian, and trace the pedigree of the Christian religion from its roots, what story would she tell? History is written backwards, hindsight is of its essence, and every attempt to characterize any great and complex historical movement is an act of retrospective construction: what is left out of the story is as significant as anything included. Is Christianity one movement or many, one story or a host of divergent narratives with few if any unifying threads?

Once upon a time historians of early Christianity could take it for granted that there were indeed true and false versions of the Christian message, right and wrong developments of its characteristic institutions. The history of the early church was the story of a single movement founded by Christ and his apostles, whose salient teachings were distilled over time into the creeds: orthodoxy, true Christianity, stood sharply defined against deviant and erroneous forms of teaching, heresy, which the church had discarded and condemned as it grew and spread.

Nowadays, we are not so sure: in a relativistic culture increasingly detached from organized Christianity, many historians are less inclined to privilege a particular story line, more prepared to view “mainstream” accounts of Christianity as the version of the foundation myth that happened to win out. In a world in which The Da Vinci Code could become a world best seller, some scholars are prepared to treat fanciful and ahistorical “gnostic” texts, written in the second century or later for esoteric groups on the margins of the Christian movement, on a par with the canonical gospels. Even sober historians nowadays are prone to speak of “Christianities” in the plural. They write of the rise of “micro-Christendoms,” the radically different and sometimes seemingly incompatible forms in which the Christian impulse, if it ever had been one impulse, metamorphosed and diversified as it adapted to changing times and cultures.

Diversity is one of the major themes of Robert Wilken’s masterly and generous-spirited account of the first thousand years of the Christian story, but he is no relativist. A former Lutheran turned Roman Catholic, he is unimpressed by the claims to mainstream status sometimes made for colorful fringe movements like Gnosticism, though he concedes their attraction in some early Christian communities. For him, under all its bewildering diversity, Christianity is clearly and recognizably one thing, an “inescapably social” movement that “entered the world as an ordered community and made its way as a corporate body with institutions and offices, rituals and laws.” “Classical Christianity” can be recognized by its distinctive marks: the initiatory rite of baptism, the ritual “sacrificial” meal of the eucharist, government by bishops, creeds, the canon of scripture.

To these he would add monasticism, that “versatile, resilient, and adaptable” lifestyle, whose proponents, free from mundane attachments, would have an important part not only in the self-definition of Christianity within the Roman Empire, but as the spearhead of its spread in cultures as different as Anglo-Saxon England, the Arab world under Islam, and the China of the T’ang dynasty.

Many of the landmarks in Wilken’s story are familiar enough: Christianity’s origin in first-century Palestine, its spread along the roads and seaways of empire, the gradual acceptance in the second century of defining institutions like episcopacy or the “canonical” group of writings that were added to the Hebrew scriptures to form the standard Bible, the recognition of the church as the privileged religion of the Roman Empire under Constantine and his successors. Christianity’s distinctive beliefs were consolidated in a series of controversies, resolved (or not) between the fourth and the sixth centuries in councils, contentious assemblies of bishops and theologians under imperial authority, in which the creeds that remain the touchstones of orthodoxy for the mainstream churches were painfully hammered out.

But the adoption of Christianity affected more than religious belief: it entailed changes that “reached into every corner of people’s public and private lives”—the division and marking of time, relations between the sexes, what one could or could not eat or drink, the conduct of war, community rituals, the framing of law, the ordering of public space. Wilken is good on the cultural transformations that Christianization brought. A sympathetic portrait of the third-century Greek-speaking philosopher and biblical commentator Origen provides a window into the transformation of Christianity into “a learned faith,” while a masterly chapter on the late-fourth-century African bishop Augustine of Hippo illustrates the maturing of Western Christian theology. Augustine, the most copious and one of the most original writers of antiquity, single-handedly generated a vast theological library that set the theological agenda in the Latin West for the next thousand years. Chapters on architecture, music, the construction of new codes of Christian law, the emergence of a Christian Jerusalem, and the creation in fourth-century Cappodocia of the first hospitals for the care of the sick and dying enable Wilken to trace the church’s accommodation to its role as the dominant religion within the Roman world.

Advertisement

But if Wilken sees in all this the authentic unfolding of a coherent movement, he is acutely aware how random and precarious the actual processes might be. The Christian movement was “inescapably social,” with a strong sense of internal unity, yet there was “no central authority” in second-century Christianity, the emergence of a canon of scripture was “a slow winnowing over several generations,” and for much of its early history, the Christian movement was riven with bitter internal controversies over its fundamental beliefs. Wilken unpacks the complexities of disputes about the Trinity and the person of Christ with an enviable lucidity.

He is clear, however, that these sometimes murderous divisions were not the symptoms of a movement without coherent identity, but just the opposite. Controversy arose precisely because “unlike the religion of the Greeks and the Romans,” Christianity was more than a set of rituals: “Christians affirmed that certain things were true” (and others, therefore, false). Such a religion “does not lend itself to every possible opinion; it imposes limits that cannot be formulated in advance, but become evident over time.”

This evolution and hardening of Christianity’s doctrinal core, into what the Victorian Cardinal Manning liked to call the beauty of inflexibility, involved both the acceptance of martyrdom and the proclamation of creeds. But it was also what gave the movement its staying power, and enabled it to prevail over the more yielding polytheism of the society in which it first found itself. Paradoxically, the existence of self-imposed limits on the adaptability of Christian belief was the key to the movement’s ability to thrive in dramatically different cultural settings.

Wilken is at pains to point out the vulnerabilities as well as the strengths of that movement. The repudiation of Christianity by the Emperor Julian, who ascended the throne in 361, is well known. Wilken brings a new dimension to the story by emphasizing Julian’s determination to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem, in order to subvert Christian claims to have superseded the older faith: the project was frustrated by Julian’s death from battle wounds in 363. That a fourth-century emperor could mobilize Judaism as a counterbalance to the growth of the church’s influence demonstrates, Wilkens argues, that there was no inevitability about the triumph of the church in late antiquity. For a movement “still in the process of finding its place in society and…torn by internal strife,” Judaism remained a serious rival, a perception that helps explain, even if it cannot excuse, the bitterly anti-Jewish preaching of the “golden-mouthed” Christian bishop John Chrysostom.

If Wilken brings new freshness and clarity to a relatively familiar story, the last third of his book explores aspects of the Christian past that will be new to many readers. The late Pope John Paul II famously lamented the ancient divisions between the Latin and Byzantine traditions that had left Catholic Christendom breathing “through only one lung.” His call for a recovery of the full breadth of Christian tradition was welcome, but the image of two lungs in which he framed it left out of account dimensions of the Christian story that could not be accommodated within such a binary scheme.

The Christianities of the Greek East and Latin West had many differences, but they shared a common formation within the Roman Empire, each in their differing ways accommodating faith with political power. But other versions of Christianity thrived without the state’s support, above all within the vast Persian Empire, and later, the Islamic caliphate. In the course of the first millennium these Oriental versions of Christianity would spread eastward from Syria and Iraq through Central Asia and along the silk roads to India, Tibet, and T’ang dynasty China. The Eastern churches accepted the definitions of the earliest councils, to that extent allying themselves doctrinally with the churches of the Empire. But they rejected, or simply never absorbed, the mid-fifth-century Council of Chalcedon’s teaching about the unification of the divine and human natures in the one person of Jesus Christ, and thereby cut themselves off from the Latin and Byzantine “mainstreams.” Their histories have until recently been almost unknown in the West.

Advertisement

Yet their achievements were stupendous. One of the most remarkable figures in their story is Timothy I, catholicos of the “Nestorian” Church of the East, who died in AD 823. A Syriac speaker from northern Iran, Timothy was educated in a monastery near Mosul in present-day Iraq, and succeeded an uncle as bishop of the Iraqi see of Beth Bagash, eventually being elected catholicos, or patriarch, of the Church of the East. Fluent in Persian, Greek, and Arabic, he was much in favor with the Abasid caliph, and at his request translated some of Aristotle’s dialectical writings into Arabic.

Timothy was learned in Islamic literature, and able to debate Koranic interpretation amiably with the caliph’s Muslim scholars. His apologetic writings against Islam remained standard resources for Syriac-speaking Christians for centuries. But Timothy was far from a mere defender of the church under Muslim rule. He took a keen interest in the spread of the gospel to new lands. He used his friendship with the caliph to get permission to repair the ruined churches of Central Asia, promoted missions to the Turks around the Caspian Sea, and appointed a metropolitan archbishop to govern the new churches there after the local king converted to Christianity. He also supported the monk missionaries who set out along the silk roads carrying only their book satchels and their staves, while his correspondence reveals that toward the end of his life he was planning to send a bishop to promote Christianity in Tibet.

The easternmost reach of this energetic Asiatic Christianity into China was forgotten or ignored in the West till recent times, after a promising start and the encouragement of the T’ang emperors had faltered and foundered by the end of the tenth century. Its once-flourishing life in Tajikstan and Uzbekistan is testified to now by shards of pottery with biblical scenes and fragmentary Christian texts in the language of the Sogdian—Iranian—empire. Wilken is intensely conscious that the vicissitudes of these forgotten churches are instances of a more general truth about the history of Christianity. Christianity was the first global religion, whose spread took it to every corner of the known world. But that exponential expansion had been halted in its tracks long before the end of its first thousand years, a success story in need of tempering with “a melancholy account of decline and in some cases extinction.”

The astonishing rise and spread of Islam in the seventh and eighth centuries brought more than 50 percent of the Christian world under Muslim rule. Latin-speaking Christianity disappeared altogether from North Africa; Greek-speaking Christianity would eventually be eclipsed in Asia Minor. At the end of the first millennium, Wilken concludes, “the great period of Christian growth and expansion was over,” and only in the Latin West was Christianity able to enter the second millennium in control of its own future.

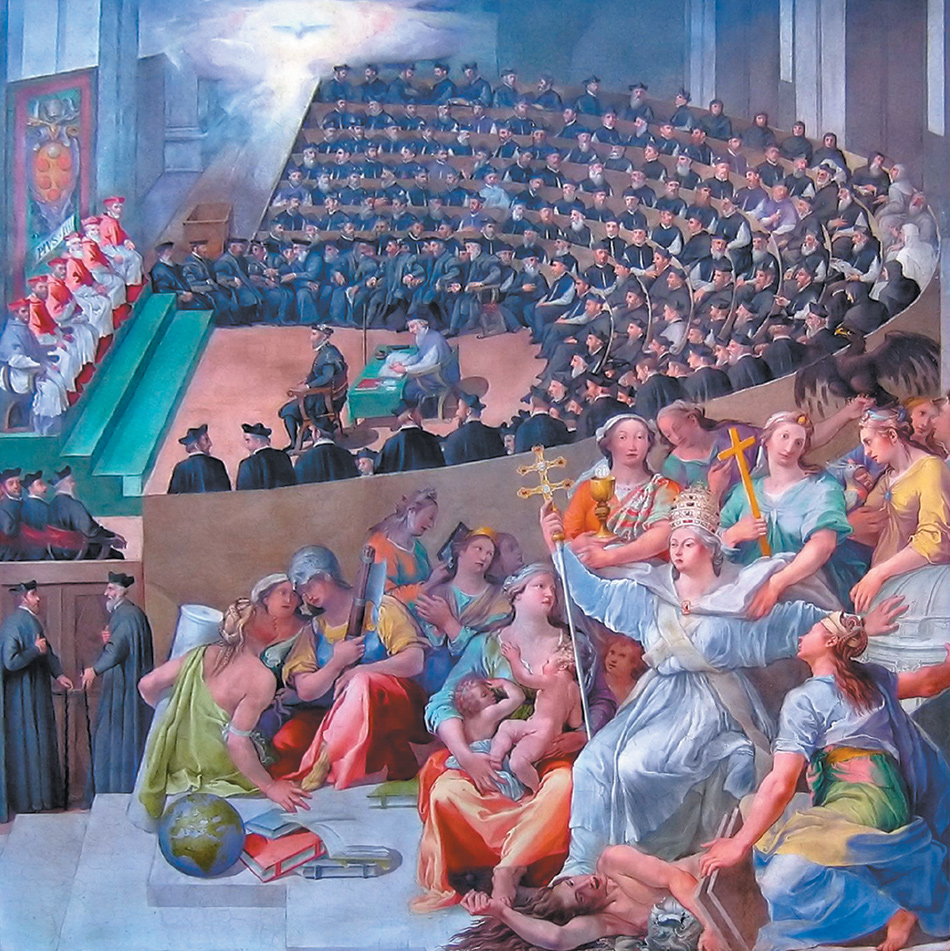

Halfway through that second millennium, Western Christianity in turn would tear itself in two. The Protestant Reformation and the Catholic response to it would create and consolidate deep and lasting divisions between the Roman Church under an increasingly centralizing papacy and the many contending varieties of Protestantism, united only by their loathing of Rome. Central both to the consolidation of early modern Catholicism and to subsequent perceptions of it was the Council of Trent, the papally convened assembly of bishops and theologians in the Tyrol that, meeting episodically between 1545 and 1563, hammered out a Catholic response to the doctrinal and practical crises of the sixteenth century, and set the course of the Catholic Church for the next four hundred years.

If Robert Wilken’s book illustrates the bewildering varieties of early Christianity, John O’Malley’s is a study in the modern mythology of a monolithic church. The Catholicism of the centuries after Trent would come to be characterized as “Tridentine,” the adjective derived from the Latin form of “Trent,” an adjective that came to symbolize unchangeable religious uniformity.

John O’Malley is the doyen of historians of the Catholic reformation. Himself a Jesuit priest, his history of the early Jesuit movement set new imaginative and scholarly standards for the study of sixteenth-century religious institutions. O’Malley transformed historical perceptions of the most established of the Catholic Church’s institutional responses to the joint challenges of the Protestant revolt and the discovery of non-Christian civilizations outside Europe, because he emphasized the flexibility and responsiveness to circumstance of the first Jesuits, in contrast to the militaristic rigidity with which the order had often been credited. Correspondingly, he is unhappy about the application of the adjective “Tridentine” to early modern Catholicism, arguing that it attributes a uniformity and indeed coherence that belie the complexities of history.

His new history of Trent sets out to bring the cold light of historical scrutiny to bear on the legends that surround the council itself and its achievements. There is, astonishingly, no modern study of the Council of Trent in English: only the first two parts of the magisterial four-volume study by the German scholar Hubert Jedin were ever translated into English, and O’Malley’s lively one-volume survey is to be welcomed on that score alone. But his scrupulously researched and balanced book is also an intervention in fraught and sometimes acrimonious controversies within the modern Roman Catholic Church.

Fifty years ago the Second Vatican Council initiated profound changes in Roman Catholic thought and practice, revolutionizing Catholic attitudes toward other churches, toward non-Christian religions, and above all toward Jews, and launching a reform of Catholic worship that, among other transformations, swept away the Latin in which the liturgy had been conducted for more than a millennium and a half. For many, these changes seemed a providential and very necessary liberation: for others they represented a radical and destructive break with Catholic tradition, which now necessitates a “reform of the reform.” Pope-emeritus Benedict XVI deplored the liturgical consequences of the post-conciliar years, and in the face of protest from many regional conferences of bishops, permitted the free celebration of the older forms of the mass. With his encouragement, a revanchist critique of the work of Vatican II targeted the historiography of the council, which, it was claimed, had been shaped by an alleged “hermeneutic of rupture” (Benedict’s phrase) in which Vatican II was tendentiously portrayed as breaking with the perceived rigidities of “Tridentine” Catholicism. The intention behind this fashionable historiography, it was alleged, was to legitimate the rootless liberalization and relativizing of the church and its message, to accommodate it to the zeitgeist.

This critique insists that the formal documents of Vatican II are in fact far more conservative than the interpretations that have been placed upon them. Its proponents demand that the conciliar texts be read with respect to their continuities with the teaching and ethos of the pre-conciliar church, rather than by any appeal to an innovatory “spirit of the council,” deduced from the polarization of ecclesiastical politics reflected in the conciliar debates. This conservative insistence on continuity rather than change as the central characteristic of the council has been satirized as the claim that nothing whatever happened at Vatican II.

O’Malley brought his considerable weight as a historian to bear on those debates, in a number of formidable interventions, culminating in his 2008 book What Happened at Vatican II. This was a valuable one-volume history of the council, which accepted its undoubted continuities with much in previous Catholic tradition. But O’Malley also insisted that Vatican II had mandated dramatic new directions for the Catholic Church, and that in its deliberations “a wider vista was trying to break through.”

There is no mention of Vatican II in O’Malley’s new study of the Council of Trent, but the book’s subtitle, “What Happened at the Council,” alerts the informed reader that there is more at stake here than mere ecclesiastical antiquarianism. His concern is to deconstruct the myth of Trent and “Tridentinism” as a timeless encapsulation of the unchanging continuities of a Catholicism immune to history. Trent, in his view, was no monolith but a straggling historical event, stretched out over two decades and often at the mercy of the European politics that had delayed its convening until all realistic hope of a reconciliation with Protestantism had passed.

The pope who convened it, the flamboyant Paul III Farnese, a genuine reformer whose early career had, however, been built on the fact that his sister was the pope’s mistress, was fearful that a strong reform agenda at the council might target papal prerogatives. The Emperor Charles V, by contrast, was determined that the council should confine itself to such practical reforms, leaving him to negotiate doctrinal compromise with his increasingly unmanageable Protestant subjects. The council met during a period of deep uncertainty within the Catholic Church itself on many of the most fraught doctrinal issues of the day. One of the three papal legates who oversaw the early stages of the council, the English Cardinal Reginald Pole, agreed with much of Luther’s teaching on the key doctrinal issue of Justification—the event or process by which a person is made or declared to be righteous in the sight of God. He absented himself from the council before it pronounced on the subject.

Twenty years later, the legate whose theological grip and diplomatic skills steered the council to its successful conclusion in 1563, Pole’s friend Giovanni Morone, had recently emerged from three years in the prisons of the Inquisition, during the pontificate of the fanatical Pope Paul IV, under threat of execution for heresy. The council itself was boycotted by Protestants, and was desperately unrepresentative even of the Catholic world: only a handful of bishops, overwhelmingly Italian, attended its opening, and at its height in the 1560s it consisted of 195 Italians, thirty-one Spanish, twenty-seven French, two Greeks (from Venetian territory), three Dutch, three Portuguese, three Hungarians, three Poles, two Germans, one Czech, and one Croat. Its critics insisted that freedom of speech and deliberation was excluded by the iron control of the papal legates, and joked bitterly that the Holy Spirit came to Trent in the postbag from Rome.

Trent’s constructive theological work was all done in its early sessions in the 1540s, above all its nuanced and masterly decree and canons on Justification, which steered surefootedly between an extreme version of Justification by Faith alone, which would empty both the church’s sacraments and human moral endeavor of any value for salvation, and a Pelagian reliance on human effort that would trivialize the depth of human alienation from God and humanity’s moral helplessness. But much of its theological reflection was rushed and partial. Trent’s treatment of the sacrament of penance dwelt almost entirely on the judicial role of the priest in confession, at the cost of exploring the role of healing and spiritual guidance and comfort in the sacrament: this emphasis on the confessor as judge was to have profound and not entirely wholesome pastoral consequences.

The council’s teaching on such contentious matters as purgatory, indulgences, and the veneration of saints and images were all hastily crammed into its last few days, and its scrappy decrees on these subjects were hurried through without discussion. And the subsequent propagation of the council’s teaching in preaching and controversy was often misleadingly remote from the conciliar decrees themselves. Trent avoided, for example, any extended discussion of the biblical canon, contenting itself with listing the books traditionally received, and the council fathers even left open the questions of whether or not the mass might be celebrated in the vernacular, or the laity given the cup, both issues on which “Tridentinism” would take a notably hard line. Trent’s most substantial practical achievement, the reform and renewal of the office of bishop, emerged gradually from the ruins of conciliar attempts to define the office of bishop in terms that the papacy saw as threatening its prerogatives. Tridentine reform of the episcopate resulted from the gradual education of bishops into the responsibilities of their office, not from enforceable new teaching.

In general, then, O’Malley shows, Trent was no monolith: serendipity and sheer human bloody-mindedness had as much to do with its successes and weaknesses as anyone’s conscious intentions, and its enactments “surely did not pass pure into the church or into the world at large.” Instead they were mediated by the fallible human beings who had to make them work—popes, princes, bishops, theologians, even painters and their patrons, who often propagated in the process the mythology of Trent rather than the council’s actual teaching. For as O’Malley’s book abundantly demonstrates, every council is a complex and unpredictable event whose consequences run far beyond the substance of its formal decisions and decrees. No human construct is timeless, and neither an ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, nor even that church itself, stands above the slippage, flux, and confusion of the tide of history, which carries us toward a future we cannot predict, and do not control.

This Issue

June 20, 2013

What Is a Warhol?

Cool, Yet Warm

Facing the Real Gun Problem