In 2010, the artists David Salle and Richard Phillips mounted a first-rate show, to which they gave the provocative title “Your History Is Not Our History,” that was about the art of the 1980s. The point of the exhibition, which included, among others, Carroll Dunham and Barbara Kruger, Julian Schnabel and Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince and Eric Fischl, Jeff Koons and Salle himself, was to set the record straight on a messily, and excitingly, varied time. The organizers wanted to show how the large and often representational paintings of the era, which were tagged “neo-expressionist”—and flew in the face of a widely held belief that painting in itself was no longer a vital art form—were part of the same quest for new and more personal approaches as the wry and analytical work of artists (and they were often women) who, at that same moment, were using photography to comment on social issues.

Whether or not the exhibition cleared up the history of the time, it provided a needed new glimpse of a decade or so in our art that, except for a few figures, has not been given its due, certainly not by museums. Thirty years later, they remain leery of taking most of these painters seriously. Although the pictures by Eric Fischl weren’t necessarily the strongest works in the show, they made a real impact on this viewer, perhaps because they were especially well chosen. Now sixty-five, Fischl was a central figure among those who, in the early 1980s, bucked the art world’s notion that oil paintings in the vicinity of six or so feet on a side had become dinosaurs. Even more daringly on his own, he made storylike, or scene, paintings that seemingly were untouched by Cubism, Surrealism, Pop art, or modern art in general. Yet his pictures felt entirely contemporary.

Showing a boy masturbating in a plastic lawn pool at night, or a barbecue underway at a pink ranch house—or adolescents stripping for a slumber party, or people sunbathing at a nude beach—Fischl captured intimate, even hidden moments that hadn’t been seen before in such a way. Much of the force of the works came from the prevalent nudity in the scenes. As in Lucian Freud’s images of sitters placed on mattresses or threadbare sofas, Fischl made nakedness feel like an agent of exposure, possibly even shame. He painted, though, without any of the English artist’s clinical solemnity. If the people in Fischl’s pictures are nude when seen in pools, or in bedrooms or kitchens, it is because we have just come upon them this way—and from painting to painting it was stimulatingly hard to tell if these people were louche or acting naturally for the circumstances.

Fischl’s art had an awakening force as well because he made the texture of everyday American life as it had been evolving since the 1950s part of his very subject. The deck furniture and the televisions playing on kitchen counters in his pictures—and the country club clothes and princess phones and Superman T-shirts and hair curlers he made part of his scenes—had appeared already in the work of different photographers, and the painter Mark Greenwold had incorporated elements like these in his often fevered and fantastical domestic images. But Fischl, working with large and enveloping sizes and a kind of plain yet urgent realist style, could give viewers the sense that a bidet, for example, or floor-to-ceiling glass doors leading to a patio, hadn’t been encountered before in art.

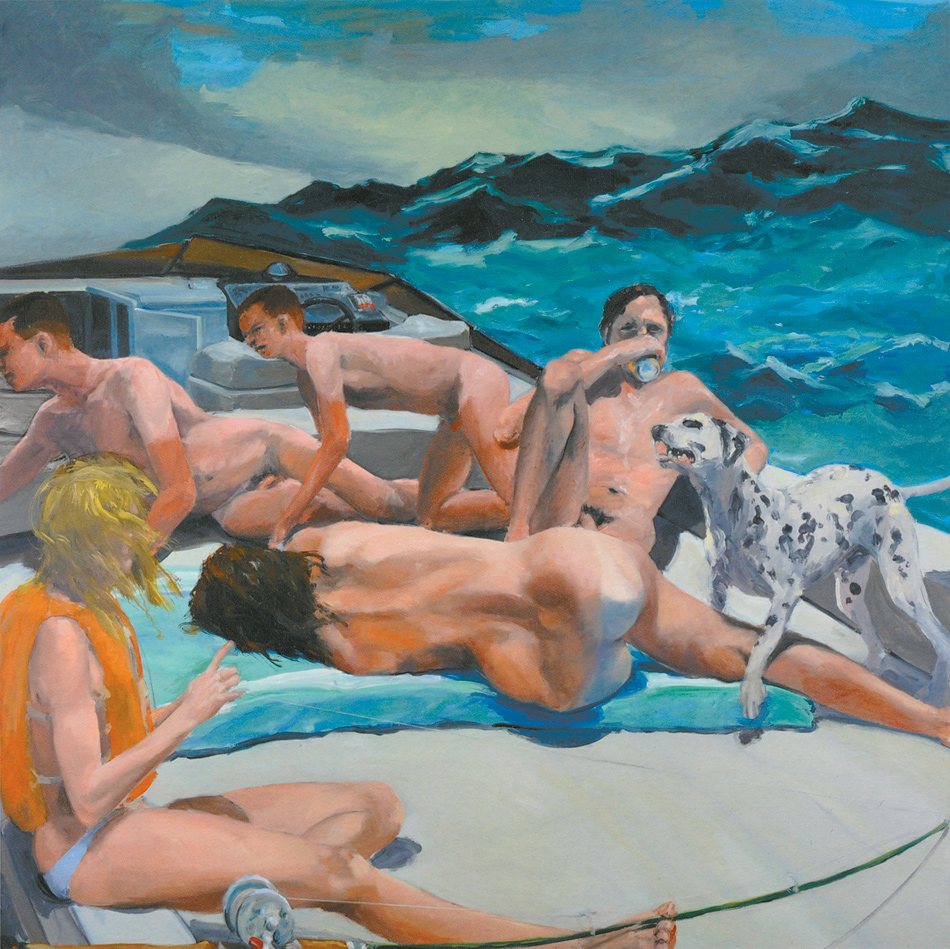

In the 2010 exhibition, some of Fischl’s pictures appeared to be as thorny in spirit and as novel in conception and design as when they first left his studio. This is certainly the case with The Old Man’s Boat and the Old Man’s Dog, a 1982 canvas that ought to be in a museum collection. It is one of the more powerful images of dissolution in modern art, although it conveys this feeling subtly and enigmatically.

The scene is the deck of a boat at the end of an afternoon’s outing. The sea is rising, the sky is lowering, and nearly everyone, including two boys, the beer-drinking “old man,” and a woman who sprawls on a mat, her backside facing us, is naked. What with the sunburned skin we see—and our imagined sense of the salty sea air, the beery breath, and the sweaty bodies—the picture can practically be smelled, and the smells suggest staleness, indifference, and incipient violence.

The painting has the scope of a moral indictment. It is easy to believe that Fischl’s partyers stand for a spent society. Yet we are left as much with the artist’s stagecraft—his canny arrangement of these bodies, with the boys heading toward something we don’t see—and, too, his highly particular color scheme. He threads together dulled terra-cotta skin tones and the water’s sour blue-greens with the black and white of an inspired touch: the “old man’s dog,” a lurching dalmatian. Dogs (labs, boxers, mixed breeds, spaniels, even basenjis) appear in a number of Fischl’s pictures from the 1980s, where, seemingly in tune with the human drama underway—or sometimes, in their stares or movements, possibly a step ahead of it—they have the presence of a Greek chorus.

Advertisement

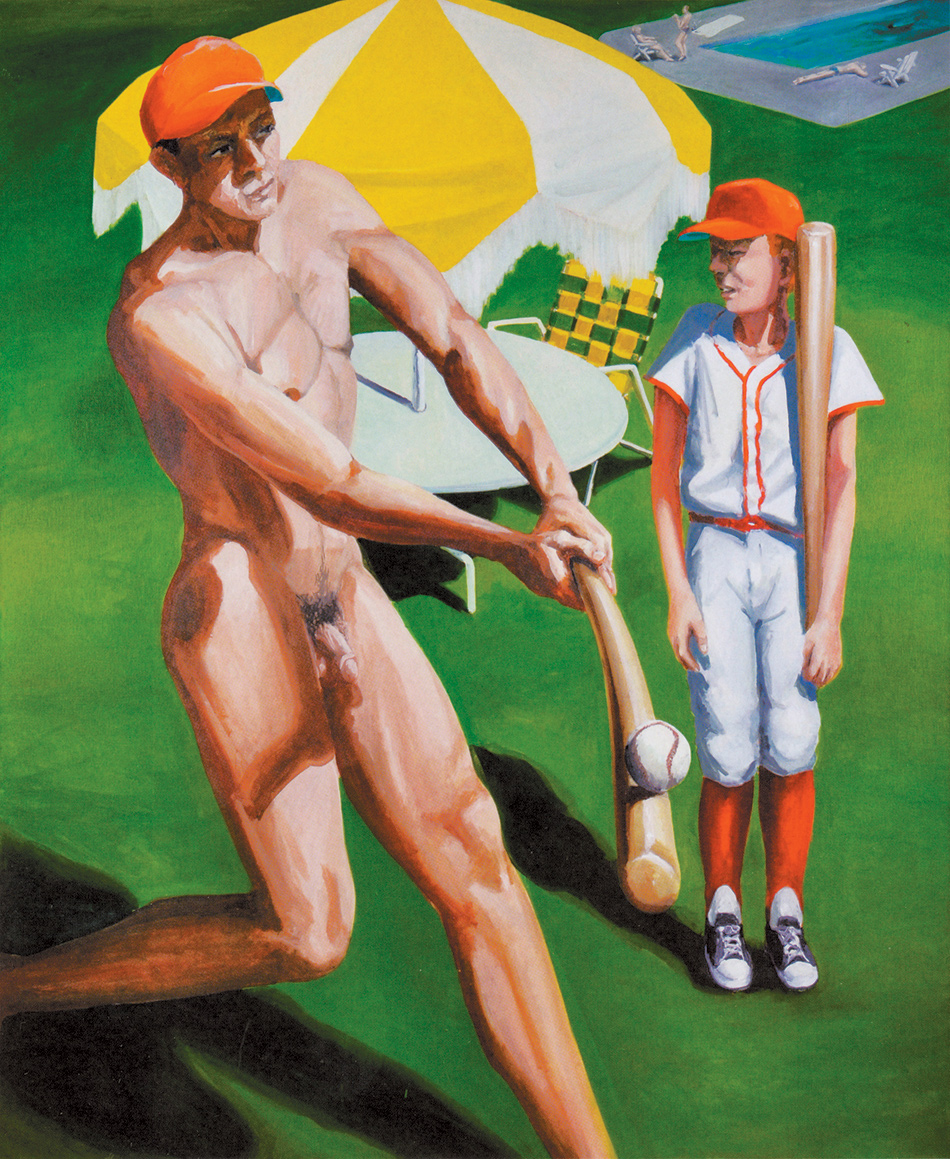

Boys at Bat, another Fischl painting in the “Your History” show, seemed even fresher than The Old Man’s Boat, not only for being relatively little known but because of its dreamlike strangeness (see illustration on page 34). The bigger boy, completely naked but for a cap, is hitting a baseball with a bat that inexplicably curves a bit. Nearby is a smaller boy in a little league outfit who scrunches up his body and face, as if he can’t look at his big pal. In the distance there are people by a pool, giving the painting the note of an American suburban scene, and one where, because of our nude batter—a swinger in two senses?—some aspect of that life is being exposed.

Yet Fischl’s image is too daringly inane to be summed up by the words “American” or “suburban.” The picture probably has something to do with the little boy’s anxiety concerning the double-barreled display of male potency before him. (If you have ever wondered if baseball bats might have symbolic connotations, this painting is for you.) Yet the words “sexual anxiety” are also insufficient. They leave out the picture’s madcap humor.

Given Fischl’s aptitude for telling stories as a painter, it probably shouldn’t be a surprise that Bad Boy, a memoir that covers his life from his earliest years to the present, is so engaging. The book, which takes its name from a celebrated 1981 painting of Fischl’s that shows a boy facing a naked woman in a bedroom, is unusual among the writings of artists in its novelistic drive and readability. Although it could stand being a third or more shorter, it spins along smoothly, folding painful family memories into accounts of the artist’s years in art school, his experiences with girlfriends and teachers, and the art scene he began encountering in New York in the late 1970s. Bad Boy has such a fine-tuned sense of detail, mood, and character one wonders how much of the book is Fischl and how much Michael Stone, his coauthor. One assumes that if the prose tailoring is indebted to Stone, everything else is Fischl’s.

The most vivid pages come at the start, in which Fischl, who grew up in and around Port Washington, on Long Island, gives us, in effect, the raw material that he later made into art. It is not surprising that family life for Eric and his three siblings was fraught. Their mother was an alcoholic, and her death, when her car crashed into a tree, is referred to as a “suicide.” His description of coming into the hospital as she lay dying, and their brief final exchange, is precise and unlabored and all the more affecting for its brevity.

The single most eye-opening bit of information in Bad Boy also arrives early on, when we learn that Eric’s parents “lounged around their bedroom…completely naked,” and that there was nothing hidden about it. Their children would “visit after dinner to watch TV.” Eric’s father Karl was a salesman for an industrial filmmaker, his mother Janet a suburban mom who had a powerful interest in art. Their nudity before their children wasn’t an aspect of her binges. It was just a part of who they were, and learning of it puts us in a kind of Eric Fischl moment, where we aren’t sure if his disclosure takes some of the mystery out of the nudity in his art—or leaves it intact.

The strongest aspect of the memoir, however, is the rounded and engaged way Fischl writes about art, whether painting in general, older art, how the artists of the 1980s realized they were “the next generation,” or where he sees art going since. One wonders whether the fullness with which he describes fellow artists and the wider world of art has a connection with his upbringing. He notes that “when a family bonds around an illness, as ours did, you never have the chance to explore and develop other reasons for staying a family.” Fischl and his wife, the landscape painter April Gornik, don’t have children. But art in all its aspects surely has given him a chance to be a family man of sorts.

Advertisement

His observations may not be startlingly original, but Fischl freshly describes, say, the way a painter and his or her painting are two very different things, and how the canvas, as it evolves, can “answer” or “surprise” the painter. He writes that light “contains mystery and revelation simultaneously,” and he is probably right in saying that since Pop art “painters have not been able to shake a certain level of doubt or self-consciousness.” His descriptions of other artists’ work are spirited and concrete, and when he draws attention to certain paintings by Edward Hopper that include beds and couples who have probably just made love, he made me see Hopper in a new, Fischlized way. About the many beds in his own paintings he writes that the bed is “a suburban counterpart to the ancestral sea with its allusions to birth, creativity, sex, sleep, and death.”

Some of the livelier thoughts in the book belong to other artists. Fischl remembers Chuck Close remarking that “when you make something that looks like art, it’s probably someone else’s art.” Alex Katz, in turn, told him that “you have to learn to paint as fast as you think. If you paint faster than your ability to focus and concentrate, you will miss your mark—and if you paint slower than your inspiration, you’ll get bored and distracted.” And David Salle, who in the early 1970s was Fischl’s studio mate at CalArts, the influential art school in Southern California, perceptively adds, “if you’re an artist, the aesthetic is personal.”

The artistic reference in Fischl’s memoir that most intrigued me, though, was to a painter one would never associate with him: Giorgio de Chirico. Fischl writes that he began one work wanting to paint bananas, and how the Italian artist was especially good on the subject. Fischl doesn’t say more about de Chirico, and this painter’s scenes, which bring together trains, arcades, and remnants of classical sculpture in forlorn and stage-set-like places, have little resemblance to Fischl’s pictures. The careers of the two artists, however, bear a striking resemblance.

The earlier painter, after roughly the years 1911 to 1917, when he made one novel image after another concerning his mythical city realm, lost his inventive power. He never stopped painting (and he wrote a good bit). But the tension he achieved in his pictures when he was in his twenties evaporated. Something like this loss has happened to Fischl. Since some point in the 1980s, his art has felt hollow.

Over the last decades, he has made a number of self-contained bodies of work. There are paintings set in India—we see people passing by one another on temple steps—while a vaguely symbolic five-part 1994 work called The Travel of Romance presents a nude white woman who in one picture is seen with a black man, her “taboo erotic fantasy,” as Fischl puts it. A third group, from 2002, called Krefeld Project, concerns a couple brooding or making love in a classically bare modern interior. Fischl concentrated for a while on portraits of friends, and in 2008 his subject became bullfighting—though, as he says, he didn’t show the expected drama of the ring but, rather, “what’s about to happen or what has just happened.”

Many of these pictures are about themes that go back to the days of The Old Man’s Boat and Boys at Bat. This is imagery that, as he writes, “evokes feelings that were once too painful or too ephemeral or too embarrassing to articulate or even to remember.” But Fischl’s later pictures feel like playacting versions of ambiguity. The lack of connection between his various figures in their moodily lit spaces is merely fancy. His ability to paint facial expressions, bodies, light, objects, and atmosphere has certainly become ever more proficient. Yet the suavely luminous style he has perfected doesn’t feel like the approach of a graspable, knowable person, whereas the just-picked-up, everyman’s realism he employed when he was starting out had exactly the right speedily functional tone for the job at hand.

Nor does he give us weirdly wonderful details any longer—details like the collection of dog crates placed on a lawn, where a woman sits smoking, in a 1980 painting. By the same token, the latter chapters in Fischl’s memoir have the substance of padded diary entries. We hear about trips and projects, famous friends and thoughts on public issues, and this reader’s mind, at least, wandered. Where is the man who showed in his pictures what queasiness, malaise, and embarrassment look like?

Self-aggrandizing as his memoir can be, Fischl is essentially accurate about the nature of his art. “There are two kinds of painters,” he writes. “One you remember for their style and energy…. Seeing their work is a physical experience,” and with them “individual canvases don’t come to mind.” He, however, belongs to “the second category of painters. I try to create images so poignant they burn into your brain, not to be forgotten.” The prose here is on the rich side. But his best pictures accomplish something quite like this.

This Issue

July 11, 2013

A Pianist’s A–V

Hard on Obama

The Unbearable