In response to:

In Quest of Blood Lines from the May 23, 2013 issue

To the Editors:

In his interesting piece on genealogy [“In Quest of Blood Lines,” NYR, May 23], Gordon Wood cites “the use of DNA to show that Thomas Jefferson was the likely father of at least some of the children of his mulatto slave Sally Hemings.” The insistent reiteration of this misconception does not make it true.

The DNA test performed in Oxford some years ago made use of patrilineal DNA derived from a Jefferson uncle. It showed only that in some generation, not necessarily Jefferson’s, the two strands of DNA were mixed. At least three Jefferson relatives (a brother and two nephews) are regarded as more likely contemporary candidates as fathers of Sally Hemings’s children.

Among molecular biologists, it is common learning that matrilineal DNA (such as was used to verify the remains of the tsar’s family before their reburial in St. Petersburg) is far more precise and reliable and capable of pinpointing the connection claimed with far greater probability. In its absence, uncertainty as to generation and donor rule. Indeed, I know of no serious historian of Jefferson, including the preeminent Dumas Malone, who has ever credited this tale. I am sure Dr. Wood will wish to recheck his facts.

Edwin M. Yoder Jr.

Alexandria, Virginia

Gordon S. Wood replies:

The evidence that Sally Hemings was Jefferson’s mulatto concubine and bore at least some of his children does not rest solely on the DNA findings. Far more convincing evidence for the relationship can be found in the powerfully argued works of historian Annette Gordon-Reed, especially her The Hemings of Monticello: An American Family (2008). In that book Gordon-Reed builds a persuasive contextual case for the relationship.

Although we know very little about Sally Hemings and her attitudes about her life as a slave, thanks to Gordon-Reed’s book we now know quite a bit about the lives and attitudes of the other Hemingses. By mastering a variety of interrelated facts and coincidences and by explaining dozens of complicated Jefferson-Hemings family relationships, both black and white, Gordon-Reed has connected a multitude of dots and answered the many doubts some historians have had that Jefferson could be sexually involved with his mulatto slave.

Especially persuasive is her account of Sally’s and her brother James’s relationship with Jefferson in Paris. In France, which forbade slavery, the two siblings could have walked out of Jefferson’s household at any time and been free. No historian seems to doubt the deal that Jefferson made with James—to return to America and train another slave in French cooking in exchange for being freed. Why then should we doubt the deal he made with Sally, a deal that her son Madison always maintained—that Jefferson would free her children at age twenty-one?

Gordon-Reed also has revealed the complex reality of white–black relations in Jefferson’s Virginia. Thomas Bell, for example, lived openly with Sally’s older sister, Mary, and had two children with her. Despite living with a black concubine, Bell was a justice of the peace and was appointed to important committees in Charlottesville; and, more important, throughout he remained one of Jefferson’s closest friends, exchanging visits in each other’s homes.

According to the DNA evidence the Carr nephews could not have been the fathers of Sally’s children. Jefferson’s brother could have, but all the other evidence points to Jefferson. Dumas Malone was a great historian, but he so worshiped Jefferson that he could not bring himself to imagine his hero’s relationship with Sally Hemings. But others, not just most Jefferson scholars today but many of Jefferson’s contemporaries, could conceive of such a relationship. In fact, such a relationship was more conceivable in Jefferson’s generation than it was in Malone’s. Mr. Yoder needs to catch up on the latest Jefferson scholarship.

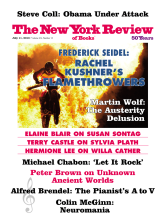

This Issue

July 11, 2013

A Pianist’s A–V

Hard on Obama

The Unbearable