In the autumn of 1892, Mark Twain, having fled to Europe in serious financial difficulty and with his wife Olivia increasingly ill, moved into Villa Viviani on the slopes of the village of Settignano, then some five miles to the east of Florence. Shortly after he arrived, he wrote to his sister-in-law, Sue Crane, that Janet Ross, who had recommended the villa to him, had put all in order:

Mrs. Ross laid in our wood, wine and servants for us, and they are excellent. She had the house scoured from cellar to roof, the curtains washed and put up, all beds pulled to pieces, beaten, washed and put together again, and beguiled the Marchese into putting a big porcelain stove in the vast central hall. She is a wonderful woman, and we don’t quite see how or when we should have gotten under way without her.1

Some seventeen years later, young Virginia Woolf spent a fortnight in Florence with her sister and brother-in-law, Vanessa and Clive Bell, and on her way back to England, she wrote to her friend Madge Vaughan, the daughter of John Addington Symonds, to whom Woolf was sexually attracted and who was to become Sally Seton in Mrs. Dalloway:

We had a tremendous tea party one day with Mrs. Ross. She was inclined to be fierce, until we explained that we knew you, when she at once knew all about us—our grandparents and great uncles on both sides. She certainly looks remarkable, and had type written [sic] manuscripts scattered about the room. I suppose she writes books. There were numbers of weak young men, and old ladies kept arriving in four wheelers; she sent them out to look at her garden. Is she a great friend of yours? I imagine she has had a past—but old ladies, when they are distinguished, become so imperious.2

Each letter reveals, as letters generally do, a certain amount about its author, but taken together, these two passages from two very different people also unwittingly indicate much about “Mrs. Ross,” who is the subject of Queen Bee of Tuscany, the extensively researched new biography by the poet Ben Downing.3

An upper-middle-class Englishwoman of limited financial means, Janet Ross lived for sixty years in Florence, where she became something of a legend as the center of its significant and sizable Anglophone society, about which so much has been written. As Virginia Woolf surmised, she had indeed “had a past.” Addressed by almost everybody as “Aunt Janet,” she knew personally, or at least entertained, almost everyone of importance who came through Florence in all those years, especially the English intellectuals, artists, and statesmen. She wrote a prodigious number of books on a variety of subjects, including a famous cookbook, Leaves from Our Tuscan Kitchen, or How to Cook Vegetables, the latest edition of which appeared as recently as 2010.

Janet lived in a castellated villa called Poggio Gherardo—poggio is the Tuscan word for a small hill—that figures prominently in Boccaccio’s Decameron, and where she held a sort of open house every Sunday afternoon, offering sumptuous teas and singing for her guests Tuscan songs called stornelli as she accompanied herself on her guitar. Unlike most women of her class, she was highly knowledgeable about farming, viticulture, and housekeeping, often laboring alongside her peasants in the olive groves and vineyards of her farms. She also produced a delicious vermouth, the recipe for which she claimed came from the last of the Medici, which was a huge commercial success in London. She was fluent in Italian, French, German, and Arabic, and she was a renowned horsewoman.

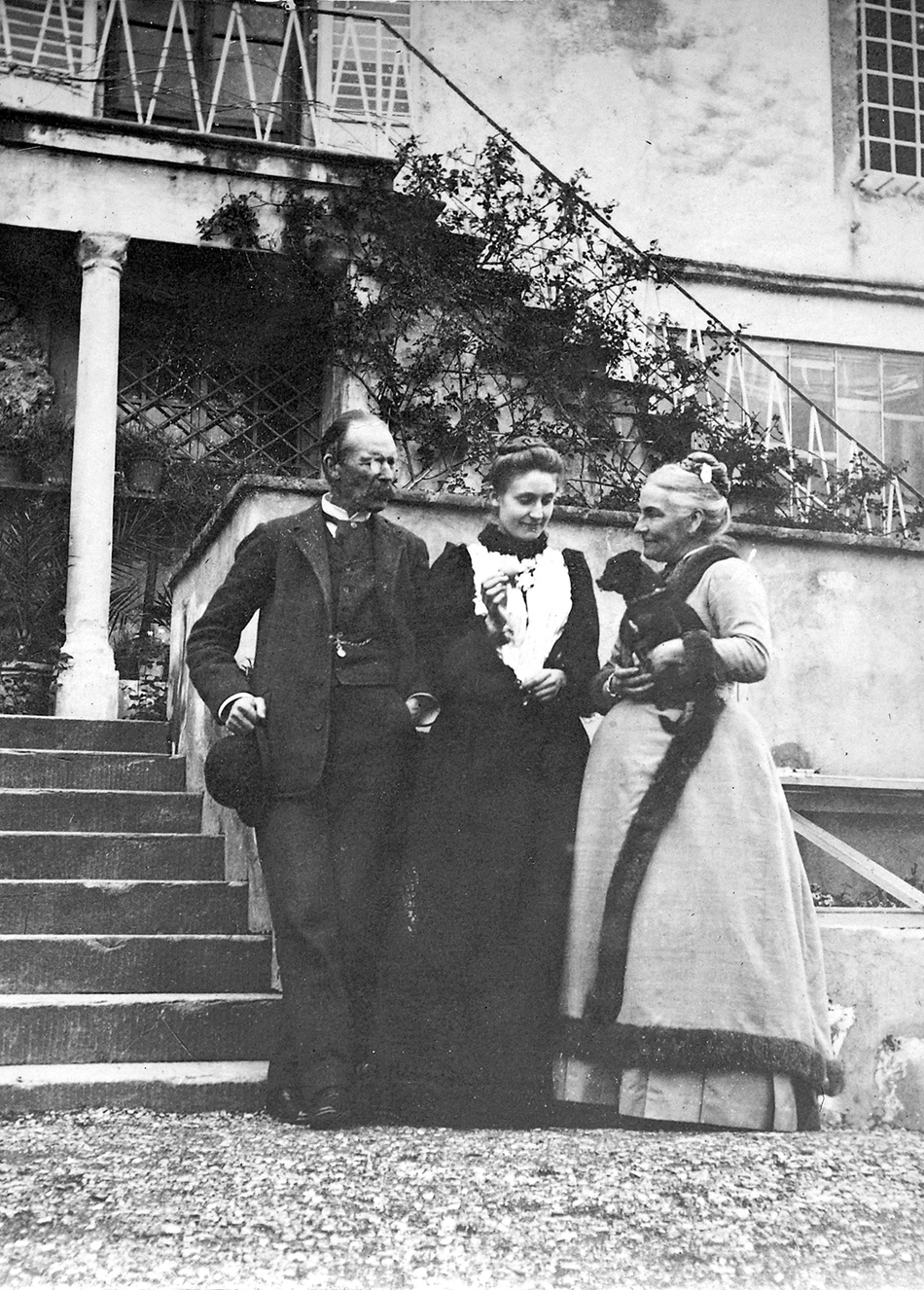

In 1925, Kenneth Clark made his first visit to Italy at the age of twenty-two in the company of Charles Bell of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, who had arranged for them to stay with Janet Ross. She was the first person Clark met in Florence, and his description of her in her old age is worth quoting:

She was a well-known terrifier but…I did not find her alarming at all…. She was a beauty. When I met her she was over eighty but the relics of beauty were still there, a classically regular face, large level eyes, thick white hair, an erect carriage. She always dressed in white, white serge by day, creamy Moroccan silk at night. This progression of whites gave a startling prominence to her fierce black eyebrows…. She was the most completely extrovert human being I have ever known, and her passions had passed like water off a duck’s back.4

There are a number of portraits and photographs of Janet Ross, but for me the most revealing is the drawing made by the Victorian artist G.F. Watts when Janet was only sixteen years old, living with her parents at their house in Surrey. His bright-eyed gamine, with a determined look and a barely concealed smile of triumph, is the cheeky girl who, when Tennyson asked her to retie his shoelace, told him to tie his own shoe. (“He afterwards,” she wrote, “told my father that I was a clever girl, but extremely badly brought up.”)5 This is the tomboy who as a young teenager distinguished herself hunting with the Duc d’Aumale’s Harriers and who, at the age of eighteen, surprised everyone by marrying forty-year-old Henry Ross because he rode so well: “I took Mr. Ross out with the Duc d’Aumale’s harriers,” she later matter-of-factly explained, “and was much impressed by his admirable riding, his pleasant conversation, and his kindly ways. The result was that I promised to marry him.” They were to remain devotedly married until his death forty-two years later.

Advertisement

Henry Ross was a partner in the English bank Briggs and Co., in Egypt, where they moved as soon as they were married. For Janet, Egypt was “exactly like our dear Arabian Nights, only the Europeans spoil it.” She especially disliked the Europeanized sector of Alexandria in which they lived, claiming it was “like a tenth-rate French provincial town”; but she adored Cairo, which was much more exotic and where she became friends with Halim Pasha, one of the sons of the great Muhammad Ali and brother of the ruler of Egypt, Said Pasha. As a wedding present, Halim gave Janet a splendid Arab stallion, and somewhat later, she challenged him to a race between an English and an Arab horse, which she won. And in February 1862, her friend Ferdinand de Lesseps took her by horseback on an inspection tour of the Suez Canal, which he was building with an appalling number of slave laborers at that time, an excursion she describes in detail in chapter 8 of her autobiographical The Fourth Generation.

In the second year of her marriage, Janet, claiming that she had no idea how it happened and that she must have been drugged, became pregnant, and on September 8, 1862, she gave birth in England to a son, Alick. When she returned to Egypt in January, she left Alick behind and for the rest of his life had very little to do with him; not surprisingly, he grew up to become a somewhat dissolute playboy, whom Janet eventually disinherited.6 One of her friends quipped that she was like “a salmon which swims up river to spawn and then swims out to sea again.”7

In 1866, with the American Civil War over and American cotton once again in competition with Egyptian cotton, the Egyptian economy suffered badly, and there was an international banking crisis throughout Europe as well, both of which caused Henry to lose a great deal of money and forced the Rosses to leave Egypt in some disarray. Realizing that they couldn’t afford to live in England, they retreated in 1867, when Janet was twenty-five, to Florence, which was known as an inexpensive refuge (Hawthorne called it a “paradise of cheapness”), and began their prolonged existence there.

The sixty years that Janet lived in Florence are chronicled in copious detail by Downing. He also makes it clear that, for all her gifts, as the years in Florence went by Janet became more and more arrogantly sure of herself, imperious, and unwilling to suffer fools, or even people she disliked, with anything but unequivocal disdain. She became notorious for insisting on punctuality in her guests, submission to her demands, and agreement with her opinions.

For their first two decades in Florence, Henry and Janet Ross lived as the tenant guests of Marchese Lotteringo della Stufa at his estate, Castagnolo, southwest of Florence, where Janet threw herself into farming, learning about olives and grapes, their cultivation, their harvesting, and the production of oil and wine. By the time they moved to Poggio Gherardo on the other side of Florence in 1889, Janet was rapidly becoming a well-known author of essays on Italian subjects in London periodicals; these essays were later collected into a volume entitled Old Florence and Modern Tuscany and are still worth reading for their descriptions of such things as the making of oil and wine, the medieval method of farming called mezzadria (a complex form of share-cropping still current in her day), Tuscan popular songs, the Florentine ghetto, and other aspects of Italian life in the nineteenth century.

Janet was, by then, an accomplished farmer as well, unhesitant in teaching her Italian peasants better ways of doing the jobs they and their forebears had been doing for centuries. Her gentle, uxorious husband seems to have taken refuge from the quotidian turmoil of an active farming estate by following Candide’s advice and quietly cultivating his private garden. He built himself a couple of greenhouses, where he tended his increasingly impressive collection of rare orchids, and a fountain to harbor his collection of exotic Burmese goldfish. He seems to have had a symbiotic relationship with animals: his goldfish would rise to the surface at the sound of his footstep, and he enjoyed the luxury of having a pet nightingale, named Cecco, who lived in the house and would perch on his knee.8

Advertisement

One has the impression that Janet’s world of middle-class English intellectuals was a very small world indeed, where everyone knew everybody. When she was five, her parents allowed her to ask to her birthday party whomever she wished. She precociously invited only five adults, all of whom came: William Makepeace Thackeray, the novelist; Lord Lansdowne, the great Whig statesman; Caroline Norton, the feminist and social reformer; Richard Doyle, the famous Punch illustrator; and Tom Taylor, the dramatist who wrote Our American Cousin, the play Lincoln was watching when he was shot. As a child, Janet used to play in Jeremy Bentham’s garden, and one of her favorite playmates, though he was somewhat older than she, was John Stuart Mill; she rode horses with the Comte de Paris and the Prince de Condé, who were roughly her age.

Both George Meredith, who was to portray her as Rose Jocelyn in Evan Harrington, and Alexander Kinglake, author of Eothen, were in love with Janet, and three of her very closest friends were John Addington Symonds and her next-door neighbors, Bernard and Mary Berenson. With proprietary familiarity, she called Meredith “my Poet,” Symonds “my Historian,” and Barthélemy St. Hilaire “my Philosopher”; George Frederic Watts, who had spent time in Italy, she dubbed “Signor” and Kinglake “Eothen.” She used to sit on Macaulay’s knee and, because she loved to hear his voice, would command him, “Now talk!”; Dickens once gave her a present of a book; and she simply couldn’t abide Carlyle.

Janet’s family seem to have taken it for granted that one should know the major languages. Sarah Austin, Janet’s grandmother, was a celebrated translator, especially of German literature, Goethe in particular, but she also translated books from Italian and French. Lucie Duff Gordon, Janet’s mother, did important translations from German and French as well; and when she was only thirteen, Kinglake asked Janet to translate a book by a German general on the Crimea, about which he was writing an extensive, eight-volume work—and she did. Later, Meredith asked her to translate a German history of the Crusades; it was published when Janet was nineteen, but, in order to boost sales, was listed as her mother’s translation.

Janet’s own writing is much like her character: direct, determined, self-confident, assertive, factual, unpoetic, and largely unimaginative. The half-dozen of her books I’ve read all share the same characteristics. She did Herculean amounts of research—on the medieval Hohenstaufen rulers in Apulia, for example—and her text is often weighted down with quoted letters and encrusted with factual data. As Downing beautifully puts it, “She wrote as she lived, and more specifically as she rode to hounds: with reckless confidence and brio, plunging ahead in linear pursuit of her quarry.”

If Janet had limited imagination, she was also, as Kenneth Clark observed, so literal-minded that she was incapable of comprehending an abstract concept, and this too is reflected in her writing. Once she asked a friend what the equator was. He explained that it was an imaginary line encircling the earth, to which she replied, “Imaginary line! I never heard of anything so ridiculous.” As it turned out, although she was much more prolific than he, Henry was the better writer, and the book of his letters that Janet insisted on publishing late in his life, Letters from the East, is vividly written and utterly engrossing.

The enchanting, spirited girl who so charmed the Egyptians and then so assiduously mastered Italian farming became, as the years progressed, more and more peremptory, more demanding, more opinionated, more overbearing. Especially egregious was her reprehensible treatment of her niece, Lina Duff Gordon, whom she adopted but then effectively rejected when she married the artist Aubrey Waterfield, a man Janet felt was too impecunious to be Lina’s husband; after several years, Lina managed to achieve a rapprochement of sorts, but Janet never accepted Aubrey. This deplorable story is fully recounted by Downing. Yet Mary Berenson testified to the warmth of Janet’s affection, and her peasants are said to have adored her. Perhaps the most moving thing ever written about Janet was this tribute in an unpublished memoir by Madge Symonds Vaughan, the woman to whom Virginia Woolf wrote her rather petulant letter:

The world will remember Janet Ross as a rather domineering and commanding figure in the literary and social circles of her day. But some there are, who, like myself, will bless this great Victorian lady because of her hidden tenderness, and because of that deeper and serener charity which touches the heart in its affliction.

Ben Downing’s biography, thorough though it is, leaves the reader with several unanswered—perhaps unanswerable—questions. One cannot help wondering why, if Janet was so infamously rude and insulting to her guests, so unimaginative, so humorless, and so self-assured, anyone wanted to come to Poggio Gherardo—yet countless people did. What attracted Mark Twain so much that he claimed he never went anywhere in Florence without stopping by Janet’s villa on the way? How did she so quickly become one of the sights travelers to Florence thought important to see? Why would a person like Virginia Woolf feel she should go to one of Janet’s Sunday afternoons? Why did the Berensons, with their fastidious selection of what they called Unsereiner (people like us) and rejection of others, enjoy her company so much, as Bernard Berenson said they did?

There is also the mystery of her sexuality. She seems to have been, like Carlyle and Ruskin, essentially asexual, and her marriage to Henry was apparently almost a mariage blanc. She appears to have had no interest in romantic love or physical intimacy. Although it has been suggested that she was a repressed lesbian and her great-grandson, the historian Antony Beevor, tells of some postcards of nude girls found amongst her papers, I think she just wasn’t very interested in sex with either males or females.

As for the Anglo-Florentine society, which the British Consulate in 1910 estimated to have been composed of an astonishing 35,000 people, in what sense may she be said to have been its queen bee, as Downing calls her in his infelicitous title? Surely she knew only a handful of the 35,000 drones, and how many actually swarmed to her hive? Were there Anglo-Florentine regulars at the Sunday teas, like those who frequented Doney’s café, or was the company comprised chiefly of people passing through Florence? But there were also a number of eminent Anglophone authors in Florence, from Walter Savage Landor and Robert Browning in the nineteenth century to Gertrude Stein, Aldous Huxley, and D.H. Lawrence in the twentieth, whom, so far as we know, Janet never met.

At this distance in time, it’s impossible to determine just what validated Janet’s imperious authority or what fully explains her renown. Yet she remains a figure legendary for both, even among present-day Florentines. Sarah Benjamin and Ben Downing have done exhaustive research on Janet Ross and the community she dominated, yet neither has been able to discover why so many in Florence’s English community were drawn to this fierce, eccentric, literal-minded, dictatorial, but also generous, warmhearted, gifted woman. Perhaps she simply reminded them all of home.

This Issue

July 11, 2013

A Pianist’s A–V

Hard on Obama

The Unbearable

-

1

Mark Twain’s Letters, edited by Albert Bigelow Paine (Harper & Brothers, 1917), Vol. II, pp. 570–571. ↩

-

2

The Letters of Virginia Woolf, edited by Nigel Nicolson (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975), Vol. I, p. 393. ↩

-

3

An earlier biography, Sarah Benjamin’s A Castle in Tuscany: The Remarkable Life of Janet Ross, beautifully written and profusely illustrated but almost unknown in this country, was published in Australia by Pier 9 in 2006. ↩

-

4

Kenneth Clark, Another Part of the Wood: A Self-Portrait (Harper and Row, 1974), p. 104. ↩

-

5

Janet Ross, The Fourth Generation: Reminiscences (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912), p. 56. ↩

-

6

The best account of Alick’s adult years is in Benjamin, A Castle in Tuscany, pp. 193ff. ↩

-

7

Lina Waterfield, Castle in Italy: An Autobiography (Thomas Crowell, 1961), p. 37. Waterfield, who went on to become the distinguished Italian correspondent of The Observer, provides the best account we have of life at Poggio Gherardo, with Janet as chatelaine, around the turn of the century. ↩

-

8

See Lina Waterfield’s affectionate portrait of him, unmentioned by either Benjamin or Downing, in the epilogue to his Letters from the East (J.M. Dent, 1902), pp. 323–332. ↩