Something in the Air, the suggestively vague title given to the English-language release of Olivier Assayas’s film Après Mai, brings to mind Thunderclap Newman’s 1969 hit of the same name (perhaps as an inescapable earworm, for persons of a certain age). Very much of its time, the song wanly if not complacently urges its listeners to “get together,” because the revolution is “here” and, assuredly, “right.” “Revolution” was an omnipresent concept in the Western world for several years beginning in 1968, although it could mean anything from an imminent sociopolitical event of considerable magnitude to the certainty that the under-thirty demographic was in the process of imposing its consumer preferences upon the world.

If the latter meaning was prevalent in the United States, especially after 1970 or so, matters were quite different in France, to the extent that a film titled After May needn’t specify a year for most people, including those born much later, to identify it as 1968. The events of May 1968, when a series of spontaneous uprisings by students in and around Paris were joined by workers at several large industrial complexes, came tantalizingly close to revolutionary conditions before being undermined, ironically enough, by the Communist Party and the trade unions. For years afterward, idealistic youth sought to regain that momentum or at least recapture that fleeting instant of liberation, that sense that life could be reinvented, that every road was open to them. A film called Something in the Air is a promise; a film called After May, on the other hand, would seem to advertise a comedown.

A recurring if fleeting image in the early part of Assayas’s movie is a crude graphic from a Youth Liberation Front leaflet: an upraised arm holds a rifle, but it also holds a flower, and it is emerging from the neck of an electric guitar. That sums up well enough the menu of contradictions on offer to the youth of 1971, those too young to have experienced the events of 1968 except as distant spectators, who wanted fun as much as they wanted revolution—much to the disgust of their older siblings, who either considered revolution to be a potentially hazardous annoyance or fun to be a petit-bourgeois distraction.

The movie is intended as a portrait of that microgeneration (which also happens to be mine; I’m older than Assayas by eight months). The story is semi-autobiographical, based on a book-length essay he published in 2005, Une adolescence dans l’après-Mai, which in turn began as a letter to Alice Debord, widow of Guy Debord, founder of the Situationist International. Assayas had been helping Alice prepare the rerelease of her husband’s films, and she seems to have asked him to account for himself.

Assayas’s movie follows a group of teenagers as they try out various roads that might lead them to a new world. His alter ego, Gilles (Clément Métayer), is a tall, slightly stooped stringbean with small, hooded eyes and a haystack of dark hair. He is an artist—he knows that much despite the prevailing gauchiste distrust of art—but he is also an idealist, and he gets involved with the activists at his suburban high school. The film begins with an actual event, a demonstration at Place de Clichy in Paris on February 9, 1971 (pressing for political-prisoner status for jailed leaders of the Maoist group Gauche Prolétarienne), which was banned, although the demonstrators showed up anyway. The response by the CRS—the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité, the notorious French riot squad—was rapid and brutal. The camera sweeps backward ahead of the zigzagging demonstrators as they are plucked one by one and beaten with rods by helmeted and goggled humanoids in rubber trenchcoats while funnel clouds of tear gas arc across the streets.

The commitment of Gilles and his friends, who have just barely escaped, can’t help escalating after this, especially since one demonstrator, Richard Deshayes, is half-blinded from having been hit square in the face by a smoke grenade. We see smoky and contentious group meetings, leaflets being roneotyped, Gilles selling the Youth Liberation Front newspaper outside the gates of his school. One night they glue posters and spray graffiti on the school’s outside walls and are chased into the woods by security guards. The next night they throw Molotov cocktails at the guards’ hut—the first of the movie’s several significant fires. One guard is hit with a rock and lapses into a coma.

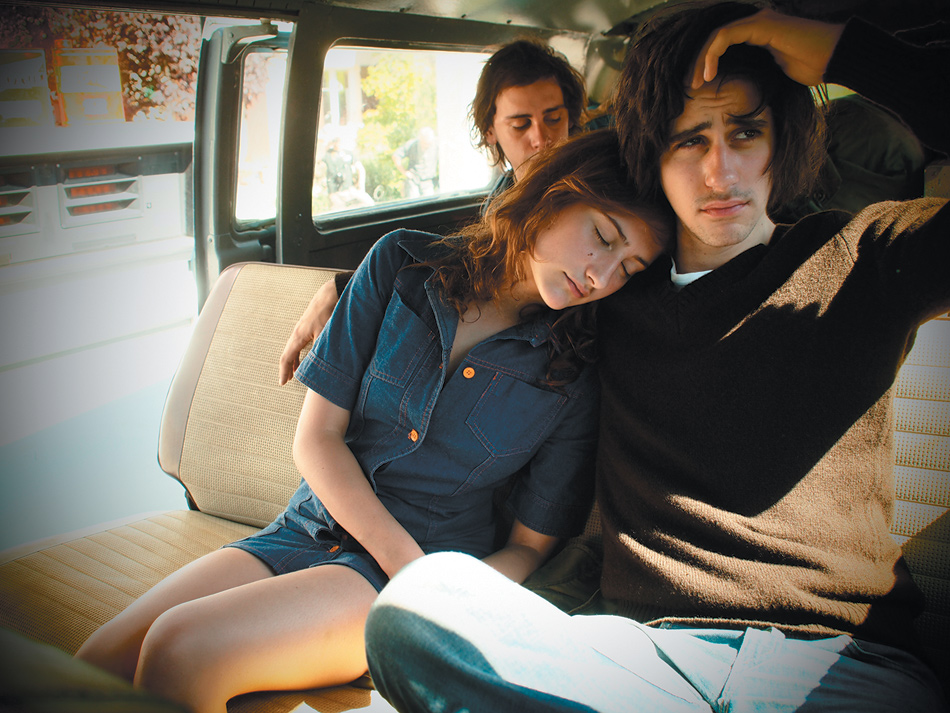

Gilles and his friends need to make themselves scarce; fortunately it’s summer. He ends up accompanying older agitprop filmmakers on a trip to Italy, although they don’t promise to be much fun. From the back of the van he mentions his enthusiasm for Simon Leys’s devastating The Chairman’s New Clothes (1971)—which laid waste to Western leftist pieties about the Cultural Revolution—and is immediately shut down by a voice from the front claiming (falsely) that the book is a disinformation exercise and its pseudonymous author a CIA agent. He and his friend Alain (Félix Armand) soon decide to take off on their own.

Advertisement

In Florence they meet an American, Leslie (India Salvor Menuez), whose father is a diplomat and who is filled with the spirit of the summer before 1968, the one of flowers and beads. Alain takes up with her and before long they are on their way to Kathmandu, although they only make it as far as Kabul. Meanwhile, Gilles has been involved on and off with two women. Sweet Christine (Lola Créton) is fully committed to the cause, so she takes up with one of the Maoists instead—although perhaps Gilles is mistaken about what sort of commitment she requires from him. The ethereal Laure (Carole Combes), on the other hand, is one minute dallying with him in a forest and the next is off again, to London, in her free-spirited way. (Most of the young people are conspicuously well-to-do.)

When Laure returns it is with a dandyish older lover and an incipient needle habit, at an orgiastic party at a country château that spirals alarmingly out of control. Hedonism, as well as Leslie’s mysticism, are shown to be alleys just as blind as the narrow political road. We leave Gilles in London, working as a gofer on a film set, something involving Nazis and a sea monster. He is also seen clutching a copy of La véritable scission dans l’Internationale (1972), the Situationist International’s funeral notice in sixty-one theses by Debord. The movie ends with a brief dream sequence projected in a theater as if it were a commercial, with a voice-over drawn from that text.

The story seems to unfold laterally, as if space stood in for time, rather like a Japanese screen or a narrative tapestry. Every scene is self-contained and cleanly executed, probably choreographed. The youthful characters make their largest decisions casually, almost randomly, or else offstage, but they are never seen fumbling or confused. The picture strictly occupies the consciousness of its characters, with no overview implied or otherwise, no recollection in tranquility, no superego. (This can be problematic since most of the young actors are nonprofessionals, and rather underdirected, so that you don’t know what if anything they are thinking. Lola Créton, already a veteran, is a notable exception to this rule.)

The fidelity to period detail is impeccable, not a hint of a false note anywhere. Sometimes this verges on the show-offy, as when Gilles flips through his records—Gong, Syd Barrett, the MC5, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, etc., at least a dozen sleeves selected with discerning taste and lovingly displayed. But Assayas gets the posturing and preening of the time exactly right: the condescending rhetoric of the filmmakers justifying their Zhdanovist approach for the alleged benefit of the working class, the cadre leader who affects the haircut and jacket of an embattled Soviet commissar in 1919 (and calls himself Rackham le Rouge, after a character in Tintin), the puritanical movement printer who gets exercised by a leaflet incorporating a smutty R. Crumb illustration, the infinitesimal shades of distinction among all the warring Trotskyite factions.

It is the movie’s political thread that is laid out, with a great many of its details carried over to the screen, in Une adolescence dans l’après-Mai (the rest is less relevant to the topic; also, Assayas has suggested in interviews that he was perhaps not as lucky with girls as his protagonist). Assayas writes of his frustration with the many forms of “Stalinism” rampant in his youth: “I’ve never hated anything as much as that willful blindness to reality, the refusal of facts, the ideologization and deformation of the world.” He notes the “many destinies sacrificed to the beliefs of the time,” when “everyone was proud to define themselves according to the things they had renounced: school, job, family, abandoned without regret.” He describes the depressing endgame of the “years of lead,” when

everything that seemed most promising of a new life, of new horizons, of an upheaval of society and all of its values was now congealed in a kind of trench warfare…. It was no longer a question of inventing anything, but rather of enduring…keeping up the pretense that we were advancing rather than stagnating.

What finally came to his rescue was the Situationist International—or rather its legacy, since that organization had folded its tent almost at the exact moment when he learned of its existence. The writings of Guy Debord and his cohort, which rejected capitalism and the various Stalinisms with equal ferocity, spoke to him immediately. He was intrigued by the Situationist program of “creating situations”—that is, to put it crudely, employing a mixture of elements that could include street theater, hoaxes, public affronts, and the hijacking of various media in an effort to supersede art and affect society directly. He was humbled, wary of the astringent “purity” and the “radical stance at once unassailable in its truth and inaccessible in its practice” of the fearsome Situationist line. And of course he was sadly conscious that he would always exist in the aftermath, an admirer of struggles gone by—and even had he been there he could have been no more than a foot soldier.

Advertisement

He resolved these conflicts by means of the cinema. Like Gilles he was a painter in adolescence, and like him he had a father in the film business. (He’s a little bit unfair to his dad in the movie. Raymond Assayas, aka Jacques Rémy, may have been, as depicted, a hack screenwriter who wrote many forgettable scripts as well as fifty episodes of the Maigret television series, but he was also an anti-Stalin leftist of evident integrity, a friend of Victor Serge, and a passenger on one of Varian Fry’s exile ships to the Western Hemisphere in 1940.) Olivier, like his character, seems to have gone to work in the business on a kind of half-desperate whim, but once there he found fulfillment, artistic and otherwise. As he tells Alice Debord, he found himself at last “creating a situation.” “What I felt then was very simple and its obvious truth determined the course of my life; I learned that there could be nonalienated collective labor” (italics his).

Alice Debord’s response, if any, is not recorded. One can only surmise the possible reaction of her late husband, the first of whose theses in The Society of the Spectacle states:

In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.

But then, as Assayas points out quite rightly, Debord not only wrote dauntingly dense arguments concerning power relations in the postindustrial world, but also devoted a book (Panegyric) and a film (In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni) to a nostalgic evocation of his own bohemian youth.

Debord’s movie is an essay-film, though, with no actors, no love scenes, no costume department, no crane shots, just a montage of stills and clips from other sources, and a plangent, rueful voice-over by its author. And how much distance is there between Assayas’s sensation-hungry but idealistic, idealistic but self-deceiving, self-deceiving but indecorously vain youngsters (they were my people, too) and Debord’s desperadoes, “people quite sincerely ready to set the world on fire just to make it shine”?

It’s of course idle to chastise Assayas for having made a commercial picture. It’s his job, and he’s good if uneven at it. Something in the Air in fact realizes a merger of what may be his two finest achievements to date, the endless, chaotic nighttime party scene in Cold Water (1994) and the political sophistication and historical specificity of his television miniseries Carlos (2010). He learned much from both experiences; the catastrophic party scene in Something in the Air is the single best thing in the movie (although some of the credit belongs to Captain Beefheart and Soft Machine for their indelible contributions to the soundtrack).

Something in the Air is an alluring picture, lithe and flowing, wonderful to look at, endlessly sensual in its evocations of youth and pleasure and how it felt to ride in a motorboat in the Mediterranean with several beautiful topless girls (even if one never actually had the pleasure). But that’s as far as it goes. It presents its viewers, and its characters, with no problems, only temporary impediments. It neither depicts nor provokes self-questioning or self-examination. Its narrative curve is that of a bildungsroman, but instead of culminating in a growth of character it leads only to a career choice. Then again, that is only fitting for a movie released in 2013, when it is all but impossible to see past the edge of the enfolding spectacle.

This Issue

July 11, 2013

A Pianist’s A–V

Hard on Obama

The Unbearable