A recent publication by the United States Army provides surprising insight into the origins of the American Revolution. Field Service Manual 3-24, released in 2006 and apparently the brainchild of General David Petraeus, explains how in the future the military might devise more effective counterinsurgency strategies. Successful counterinsurgency operations, of course, require an informed grasp of the political and cultural wellsprings of insurgency. It is not an easy task. As the report states, “every insurgency is contextual and presents its own set of challenges.” But whatever the differences may be, we learn that all insurgencies “use variations of standard themes and adhere to elements of a recognizable revolutionary campaign plan.”

Although defeating these movements requires “contemporary experiences,” it is also wise to draw upon “historical studies.” The manual mentions in passing the French Revolution but, predictably, most examples of insurgencies come from more modern times. One common form of insurgency involves “struggles for independence against colonial powers.” In such cases—as in other types of insurgencies—it is a good idea for military planners to study how “ideology and religion” energize resistance to established regimes. The use of overwhelming force seldom achieves positive results. “Though firmness by security forces is often necessary to establish a secure environment,” the Manual explains, “a government that exceeds accepted local norms and abuses its people or is tyrannical generates resistance to its rule.”

General Thomas Gage, the officer dispatched to Boston in 1774 to restore British authority in New England, confronted an almost textbook case of insurgency. His colleague General Henry Clinton, who arrived in America just in time to participate in the Battle of Bunker Hill, was horrified to discover that “insurgents had seized every avenue from the surrounding country.” He confessed that while the Americans were “badly armed…without discipline or subordination,” they still managed to organize a force “respectable for its numbers and the enthusiasm by which they were actuated.” Gage never overcame the shock of fighting an enemy that employed what today might be called guerrilla tactics. The Americans, he observed,

deriving confidence from impunity, have added insult to outrage; have repeatedly fired upon the King’s ships and subjects, with cannon and small arms, have possessed the roads, and other communications by which the town of Boston was supplied with provisions.

He was unprepared to counter people who “make daily and indiscriminate invasions upon private property, and with a wantonness of cruelty…carry depredation and distress wherever they turn their steps.”

Whatever terminology military figures such as Clinton may have used to describe the Americans who cut off Boston from the rest of New England, historians of the Revolution have been reluctant to call them insurgents. Like other respected scholars of the period, Nathaniel Philbrick, in his new book, Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution, depicts the imperial controversy before independence as largely a contest between patriots and loyalists. The problem with these familiar terms is their failure adequately to reflect the extraordinarily fluid conditions before the Revolution.

In that sense, labeling all Americans who openly challenged British authority during 1774 and 1775 as patriots involves an awkward teleology. We know that the colonial resistance succeeded; Americans did in fact create a new republic. But for the farmers who flocked to Lexington and Concord in April 1775, independence was not a goal. They wanted Parliament to restore their rights. Indeed, even the men who took up arms against the British protested their loyalty to the crown. Joseph Warren, who became a leading spokesman for resistance in Massachusetts, insisted as late as the summer of 1774:

Nothing is more foreign from our hearts than a spirit of rebellion. Would to God they all, even our enemies, knew the warm attachment we have for Great Britain, notwithstanding we have been contending these ten years with them for our rights!

The odds were very much against the insurgents. If George III and his ministers had been willing to offer concessions, even to negotiate in good faith, the rebellion would never have set off a revolution.

Nathaniel Philbrick picks up the story of colonial American resistance during the aftermath of the destruction of a large shipment of tea in Boston Harbor in December 1773 by a group of insurgents calling themselves the Sons of Liberty. They claimed that under the British Tea Act they would, in effect, be forced to pay a tax on the newly arrived tea, without having had any say in the act’s passage. The British responded to this provocation with a series of punitive acts, known collectively in the American colonies as the Coercive Acts. The most infuriating piece of legislation closed the port of Boston in 1774 to all commerce. A great many laborers were thrown out of work; the cost of consumer goods skyrocketed. Philbrick draws attention to the developing resistance movement in Boston, especially to the tireless efforts of Joseph Warren, who along with Samuel Adams and others encouraged discontent.

Advertisement

But as significant as the Boston protesters were to the challenge to British authority, they could not have transformed chronic complaint and scattered protest into full-scale rebellion without the support of what Philbrick calls the “country people.” The insurgency swept up thousands of farmers who lived in small inland Massachusetts communities. They seem unlikely participants in such a movement. For the most part, they were prosperous landholders who enjoyed a level of personal freedom that their European contemporaries would have envied.

As the Army’s counterinsurgency manual reminds us, however, material conditions seldom provide a sufficient explanation for organized popular resistance to established authority. The farmers who flocked first to Concord in April 1775 and then two months later to Bunker Hill were frightened and angry. Occupation by the British troops brought home to the Americans their utter dependence on the will of Parliament, a body in which they lacked representation. The possibility of military coercion encouraged a growing belief in Massachusetts that the British government conspired to take away their God-given rights and reduce them to slavery. The claim may seem hypocritical, since at the time many New Englanders owned black slaves. But white colonists saw no conflict. In the terms of eighteenth-century political rhetoric, they feared a complete loss of personal freedom.

Whether imperial authorities actually entertained such designs is less important than the fact that ordinary New Englanders were certain that there was a plot against their liberty. As Warren warned the country people:

Our all is at stake. Death and devastation are the instant consequences of delay. Every moment is infinitely precious. An hour lost may deluge your country in blood, and entail perpetual slavery upon the few of your posterity who may survive the carnage.

The insurgents insisted that since God had given them their rights, they had a responsibility to the Lord to preserve them, even if that meant armed confrontation with British troops. General Gage and other officers blamed the New England clergy for stirring up trouble. They had a point. For example, Corporal Amos Farnsworth, an American soldier, reported hearing a sermon delivered soon after the battles of Lexington and Concord. “An Excelent Sermon,” Farnsworth recounted in unschooled language, “he [the Reverend William Emerson] incoridged us to go And fite for our Land and Contry: Saying we Did not do our Duty if we did not Stand up now.” The historian Charles Royster, who has studied the motivations of fighters during the Revolution, observed, “Religious and political appeals to the soldier combined the forces of the two most powerful prevailing explanations by which revolutionaries understood events.”*

The British administration led by Lord North never seriously considered defusing the American crisis. Vexed by repeated colonial resistance, they decided that the application of overwhelming force would swiftly crush the insurgency. In London the argument was persuasive. After all, Great Britain possessed the most formidable army and navy in the world. The colonists did not have a chance against such a powerful opponent. Moreover, British leaders found it hard to take the colonial military threat seriously. The Americans had had almost no formal training; they were frequently short of gunpowder. As one British officer announced just before the fighting at Concord, although the Americans “are numerous, they are but a mere mob, without order or discipline, and very awkward in handling their arms.”

A few years earlier Gage had affirmed the use of large-scale force. Writing to a superior in London, he advised, “Quash this Spirit at a Blow without too much regard to the Expence and it will prove oeconomy in the End.” And just before assuming the command of British troops in America, Gage won the heart of George III by observing that the Americans “will be Lions, whilst we are Lambs, but if we take the resolute part they will undoubtedly prove very meek.” Such boldness was just what the king wanted to hear. He announced soon after the conversation that Gage has the “character of an honest determined man.” In Parliament, backbenchers brayed for blood. In 1774 one member declared that he was of the opinion “that the town of Boston ought to be knocked about their ears, and destroyed.” Soon, several thousand regular troops occupied the rebel city.

In Boston, the terrible reality of the American situation quickly became apparent to General Gage. He found himself penned up in the city along with his forces, and his tough rhetoric about lions and lambs did nothing to clear the Massachusetts countryside of armed farmers. He tried desperately to explain to the king that Boston was no longer the immediate problem. The army faced a huge popular mobilization. Resistance to the authority of the crown had once “been confined to the Town of Boston…. But now it’s so universal there is no knowing where to apply a Remedy.”

Advertisement

Even before fighting occurred, Gage begged his superiors for substantial reinforcements. On their part, the king’s ministers found Gage’s whining annoying. They were determined to teach the Americans a political lesson and urged Gage to move his forces outside of Boston. Spies reported that the buildup of British forces had not discouraged the American insurgents. Just the opposite had occurred. They were preparing for armed conflict. Time was running out.

To bolster his sagging reputation in London, on the night of April 19, 1775, Gage ordered a large contingent of regular troops to Concord, a town rumored to house substantial military supplies to be used by the insurgents. From the British perspective, the entire operation was a disaster. Not only did the killing of Americans at Lexington instantly create martyrs, but also news of the fighting rapidly spread through the other colonies, transforming neutrals and doubters into active supporters of the American cause.

Philbrick is especially good at recounting the personal experience of battle. Drawing on diaries and letters, he recounts how ordinary militiamen witnessed the deaths of friends and neighbors. Nothing in their lives had prepared them for this moment. For some, a desire for revenge inspired courageous action. For others, the will to fight proved transient. Fighting without a clear structure of command—often with every man fighting on his own—the insurgents hounded the retreating British forces all the way back to Boston. It is a familiar story, and Philbrick tells it well.

Throughout the crisis, the American chain of command remained loose and overlapping. Most insurgents came from local militia companies that elected their own officers. In the political vacuum caused by the British retreat from the countryside in 1775, the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts increasingly directed military affairs, appointing senior officers and collecting arms. Because the military situation was so fluid, however, the Provincial Congress was compelled to create a small Committee of Safety authorized to issue orders in cases of emergency.

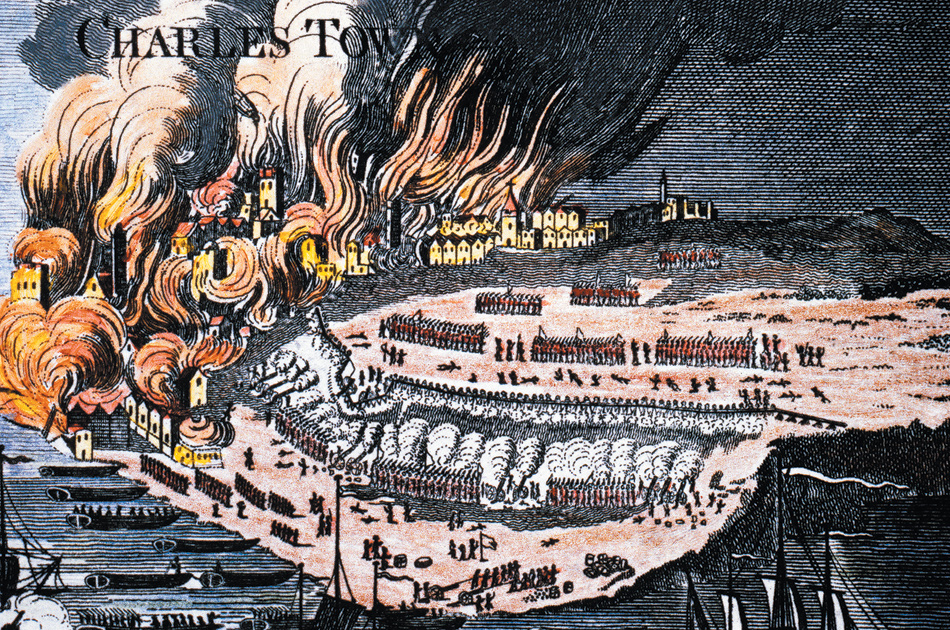

Between the moment of the British retreat from Concord in April and the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, the character of the imperial controversy changed dramatically. The ill-organized, poorly trained American soldiers—most of them militiamen from Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Connecticut—encircled Boston. Estimates of the size of the army were impressionistic, but a common figure that circulated at the time was 20,000. To put this number in perspective, the entire population of Boston was little more than 16,000. After Concord, Gage learned from a secret source that the insurgents had decided that when hostilities began “the first opposition would be irregular, impetuous, and incessant from the numerous bodies that would swarm to the place of action and all actuated by an enthusiasm wild and ungovernable.”

This huge insurgent force soon began to worry political leaders such as Joseph Warren and Samuel Adams. The enraged colonial farmers may have wanted to liberate Boston, but they did not accept orders from officers they did not know. In their encampments they fired their weapons so indiscriminately that they endangered the safety of other American soldiers. But most alarming was the growing sense among these men that the insurgent army spoke for the people. They began to question the legitimacy of civil authority. In May, Warren wrote to Adams, declaring:

I see more & more the Necessity of establishing a civil Government here and such a Government as shall be sufficient to control the military Forces, not only of this Colony, but also Such as Shall be sent to us from other Colonies. The Continent must Strengthen & support with all its Weight the civil Authority here, otherwise our Soldiery will lose the Ideas of right & wrong, and will plunder instead of protecting, the Inhabitants.

The Americans hated military routine; many simply went home to harvest crops and visit their families. In this situation, colonial leaders such as Warren concluded that unless the men soon took up the fight against the British, the entire resistance movement might collapse. On their part, Gage and his officers came to a similar conclusion. The British regulars were not only bored, but also eager to avenge the humiliation at Concord. It was only a question of which side would light the fuse.

To confuse matters even more, General Gage no longer enjoyed the trust of Lord North’s ministry. Although Gage was technically in command of the British forces in America, his superiors in London clearly believed that he did not possess the will to deal effectively with the crisis, and they sent three new generals to Boston to prod the slow-moving Gage into action. William Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne were thought to have the ability to break out of Boston and to defeat the insurgency once and for all. In June 1775 the group devised a complex plan to seize Dorchester Heights and Bunker Hill, neither of which the Americans had bothered to fortify. If nothing else, the operation promised to demonstrate to the Americans that they could not possibly hold their own against a well-drilled professional army. The British scheduled the assault to begin on June 18. Before the final moment of attack, they tried to observe strict secrecy.

Boston held no secrets. Spies quickly communicated the intelligence to Sam Adams and other American leaders, and although they concluded that the British move required a firm response, they found it extremely difficult to coordinate the scattered, independent military units. Artemas Ward, the senior Massachusetts general, had no authority over troops from Connecticut. When it came to tactics, the ranking general from Connecticut, Israel Putnam, seemed to have a mind of his own. Finally, Colonel William Prescott received orders to march about one thousand American militiamen to Bunker Hill, where it was expected that they would construct a small fort. The American goal was to counter the British plan without putting too many soldiers in harm’s way, and Bunker Hill was beyond the reach of the British naval batteries.

For reasons known only to himself, however, Prescott marched his men during the early morning hours of June 17 past Bunker Hill to a lower, much more exposed place on Breed’s Hill, where he instructed them to build an earthen redoubt. Within a few hours, the farmers threw up an impressive fortification. When dawn revealed that they had in fact occupied a position only a few hundred yards from British guns, many men panicked. One colonist declared that he feared “that we were brought there to be all slain, and I must and will venture to say that there was treachery, oversight, or presumption in the conduct of our officers.” Prescott never flinched. He had badly miscalculated his tactical position, but his extraordinary courage helped calm the Americans who chose not to flee Breed’s Hill.

However indecisive Gage may have been, he could not ignore such a blatant provocation. He selected William Howe to take charge of the attack. It was not until mid-afternoon, however, that the British assembled several thousand troops on the slope of the hill. Perhaps because he underestimated the American resolve to fight, Howe elected to arrange his soldiers in an open-field formation, and with great difficulty they made their way over uneven terrain toward Prescott’s redoubt. The Americans’ greatest concern was lack of sufficient gunpowder. Knowing that his men had only a limited number of shots, Prescott ordered them to hold their fire until the British had almost overrun their positions. At the last second the Americans cut down scores of redcoats. Whether anyone shouted “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes” is not known.

Howe organized a second assault with no better result. Finally, on the third try, he adopted a different formation—the British marched up Breed’s Hill in tight columns. With their powder almost exhausted, the Americans retreated as best they could. The American casualties were substantial. Warren, a crucial figure in organizing resistance, was killed. But their losses seemed insignificant when compared with those of the enemy. About half the British soldiers who participated in the battle—forever identified as the Battle of Bunker Hill—were either killed or wounded.

Neither side celebrated the results of the day. Many Americans insisted that if they had had a sufficient supply of gunpowder they would have driven the British from the field. Gage’s troops recognized that their victory actually represented a severe setback in their effort to pacify the rebels. As General Clinton later observed, “A few more such victories would have shortly put an end to British dominion in America.” Gage could not explain how the Americans had managed to mount such effective resistance. Reflecting on his earlier experience during the Seven Years’ War, he concluded, “These People Shew a Spirit and Conduct against us, they never shewed against the French, and everybody had Judged of them from their former Appearance and behavior…which led many into great mistakes.”

Never again did the British attempt to break out from the confines of Boston. On March 17, 1776, the entire British force, accompanied by many families who supported the crown, left the city by ship. The anniversary of this event is still known in Boston as Evacuation Day. The British regrouped in Halifax, preparing for a new campaign that would center on New York City.

George Washington reached Boston soon after the Battle of Bunker Hill. When he heard the news, he reportedly asked whether the Americans had “stood the British fire.” When he learned that they had done so, Washington remarked, “Then the liberties of our country are safe.” He also recognized that the moment of insurgency had passed. He was determined to raise a genuine army, manned partly by Continental troops schooled in proper military drill. But he owed a debt to the thousands of New England farmers who had defended their rights. Their resistance to imperial authority made it possible for other Americans to imagine independence and the creation of a republic. This was the origin of a new nation, which after nearly two and a half centuries finds itself obsessed with counterinsurgency.

This Issue

July 11, 2013

A Pianist’s A–V

Hard on Obama

The Unbearable

-

*

Charles Royster, A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and the American Character, 1775–1783 (Norton, 1979), p. 18. Another perceptive study is John Shy, A People Numerous and Armed: Reflections on the Military Struggle for American Independence (Oxford University Press, 1976). ↩