In response to:

An Exchange on John Brown from the May 9, 2013 issue

To the Editors:

Christopher Benfey snickers at David Reynolds’s calling Hawthorne a “doughface” Democrat [“An Exchange on John Brown,” NYR, May 9]. And he distorts my critique of Hawthorne in The Abolitionist Imagination [“Terrorist or Martyr?,” NYR, March 7]. As I note, Hawthorne’s politics were even more disgraceful.

An anti-Lincoln Copperhead Democrat, Hawthorne advocated “amputation,” hoping that the Confederacy would remain a separate slaveholding nation. This is precisely what the Confederacy wanted. No wonder that Confederates viewed Copperheads as allies, funding their newspapers and encouraging their leaders, including Hawthorne’s close friend Franklin Pierce. General Robert E. Lee urged President Jefferson Davis “to give all the encouragement we can…to the rising peace party of the North.”

Not surprisingly, Hawthorne had little sympathy for slaves. He thought that masters and slaves in the South lived together in comparative “peace and affection”: “I have not…the slightest sympathy for the slaves,” he declared in 1851, “or at least not half so much as for the laboring whites, who, I believe…are ten times worse off than the Southern negroes.”

Benfey suggests that Hawthorne resembled the Quaker John Greenleaf Whittier in his antiwar sentiments. But the two men stood worlds apart. Whittier, like most other antislavery pacifists, supported the war because he knew that “there could be no durable peace until [slavery] was extirpated”: “We must be ‘first pure’ before we can be ‘peaceable.’” Unlike Hawthorne, Whittier recognized, as did ex-slaves and John Brown, that slavery was itself a state of war.

Benfey largely interprets John Brown through the lens of Hawthorne, rather than placing him in the context of belligerent Southerners. This is a bit like viewing Lincoln through the eyes of Copperheads. He suggests that Brown’s Southern enemies have never been canonized and are already recognized as “wicked.” But throughout most of the twentieth century, scholars—led by “neo-Confederate” New Critics and Agrarians—have demonized Brown and canonized his proslavery opponents, from Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stewart to Robert E. Lee.

There is much to admire in Hawthorne, most notably the pleasure of reading him. But one must not confuse his art with his sectional and racial politics. His friends recognized this. Emerson received a copy of Hawthorne’s 1864 book, Our Old Home, dedicated to Franklin Pierce. While most Republicans considered Pierce a traitor, Hawthorne called him the most steadfastly loyal American. Emerson simply “cut out the dedication” and then read the book with pleasure, thus separating Hawthorne’s ignoble politics from his beautiful art.

John Stauffer

Professor of English, American Studies,

and African and African American Studies

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Christopher Benfey replies:

It seemed of interest that Hawthorne explicitly chose to align his opinion of Brown’s raid with that of Whittier, a man of quite different political convictions. “My Yankee heart stirred triumphantly when I saw the use to which John Brown’s fortress and prison-house has now been put…,” Hawthorne wrote, after visiting Harpers Ferry in 1862. “The engine-house is now a place of confinement for Rebel prisoners.”

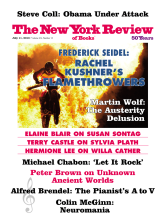

This Issue

July 11, 2013

A Pianist’s A–V

Hard on Obama

The Unbearable