About twenty-five years ago I read many of these letters, in libraries and archives, for a book on Willa Cather published by the British imprint Virago, dedicated to breathing new life into classic, neglected, or forgotten women writers. Cather wasn’t exactly neglected in Britain in the 1980s, but like many notable twentieth-century American women writers (Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor, Ellen Glasgow, Jean Stafford) she did not have the status she deserved. I wrote my book in the hopes of attracting more British readers to her work.

In the quarter of a century since then, there have been dramatic shifts in Cather’s reputation. Fierce Cather wars have raged in the American literary and scholarly world, not entirely unlike the battles that are fought over Jane Austen’s legacy. The celebration of Cather as an American pastoralist, a kind of midwestern Robert Frost, which greeted her books when they were published, still continues. Since her death in 1947, many readers still take her to their hearts as the standardbearer of a sentimental nostalgia for vanished American values. It is an appropriation at odds with the harshness, violence, and cold truthfulness that run like dark steel through the calm, lyric simplicity of her writing.

In 2002, Laura Bush hosted a White House symposium on the legacy of women in the American West, in which Willa Cather was a prominent figure. The Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial and Educational Foundation, founded in 1955 in Cather’s home town of Red Cloud, Nebraska (where many of her letters are housed), was awarded a large National Endowment of the Humanities grant in 2006 to develop its work, which includes maintaining a slice of Nebraskan prairie as “Catherland,” curating the Cather childhood home, holding Cather conferences, and publishing a Cather newsletter.

Some hagiographical reverence colors these activities, and sustains the legend of an essentially Nebraskan Cather, rather than a Cather who belongs to the international modern world. Pitched against the Cather “legacy” industry has been the feminist critical approach to Cather that started with Sharon O’Brien’s influential biography of her early years, published in 1987, identifying Cather as a lesbian artist writing a story of desire in her fiction that had to remain coded and covert. That “outing” of a queer Cather in the late 1980s, a literary movement very much of its time, was followed by an interest in Cather as a writer more concerned with politics, economics, race, modern life, and multiculturalism than her traditional admirers have allowed.

It began to seem as if Cather’s fate was to embody the rifts in the American academy between theory (or “political correctness”) and humanist aestheticism (or “conservatism”). If this is lowering to the spirits of the nonspecialist, nonacademic reader of Cather, it is also a mark of her status. Sixty-six years after her death, Cather has become, once again, after a period in the doldrums, a central figure in the American literary pantheon.

Now, Cather’s posthumous life is being transformed again by a publication that, for all Cather scholars and biographers, has been a very long time coming. In the will she made in 1943, Cather embargoed the publication of her letters—and the dramatization and adaptation of any of her work “whether for the purpose of spoken stage presentation or otherwise, motion picture, radio broadcasting, television and rights of mechanical reproduction, whether by means now in existence or which may hereafter be discovered or perfected.” As, in old age, she became more famous and sought-after, and at the same time more alienated from the postwar world, she frequently “begged” her friends to “destroy all her letters,” and not to show them to anyone. When the great love of her life, Isabelle McClung, died in 1938, Cather had her letters returned and burned them. She deployed evasive action with fans and journalists. She frequently insisted that it was for her work she wanted to be known, not for her life story, and made great efforts to preserve her privacy.

All of us who have worked and published on Cather, and who have read some of the three thousand or so letters that remain from her life’s correspondence with friends, family, publishers, colleagues, admirers, and fellow writers, had to obey the embargo she left in her will against their publication. As a result, her letters have been paraphrased over and over again by critics and biographers. Her story was told, her secrets were known, but the voice of her letters was not heard.

This embargo was adhered to until the last Cather relative and executor, a very long-lived nephew, died, in 2011. Before then the way toward the publication of the letters had been opened with a Calendar of Cather’s letters in 2002, by Janis Stout, one of Cather’s biographers. It paraphrased over 1,800 of the letters, and was then expanded and digitized, with the help of another Nebraska Cather scholar, Andrew Jewell. These two editors have now edited about 20 percent of Cather’s surviving letters for the seven-hundred-page book under review.

Advertisement

Stout and Jewell maintain that Cather was not as obsessed with privacy as some of her biographers (notably James Woodress, in 1987) have argued. They say that if she had systematically set out to recall and destroy her correspondence, much of it would not have survived; that friends and family, who would have known what she wanted, carefully preserved their Cather letters; and that she was a “skillful self-marketer” who wanted to “shape her own public identity.” This justification for publishing the letters is not entirely convincing, given the crotchety tone of many of her later remarks about intrusion—as of the “modern and abrupt” young man who wrote to her in 1934 wanting to know about her friendship with Sarah Orne Jewett, and who was told to call on “January 1, 1990.”

But surely no justification is needed. Sixty-six years after Cather’s death, her story is known, her work is securely established, her biography has been written and rewritten. Setting aside her will was the right thing to do. She is a very great writer, and the more we know about her, the better. But should the writer’s last commands not be adhered to in perpetuity, you will ask? To which I can only reply that I admire and am grateful to Max Brod and Leonard Woolf for ignoring the final commands of Kafka and Virginia Woolf that their papers should be destroyed. And I look forward to a full biography of T.S. Eliot, even though he forbade it. Writers deserve all the after-lives they can get, if it means they continue to have readers.

Paraphrase has done Cather a long disservice: it is flattening, and often misleading. Here is one small but telling example. In middle age, Cather was frequently asked about the real-life models who inspired her characters. She would respond to this ambivalently, sometimes evoking particular individuals whose memories had stayed with her, sometimes resisting all attempts to pin fictional characters down to their origins. In 1932 she wrote a story called “Two Friends,” about a child in a small Nebraskan town who hero-worships the two big men of the community, Dillon the Irish banker and store owner, and Trueman the Republican poker-playing cattleman, whose impressive friendship founders on politics. Cather wrote to her old Red Cloud friend Carrie Miner Sherwood, whose father had been the Cathers’ neighbor and the main merchant of Red Cloud when Cather was growing up there in the 1880s and early 1890s:

You can never get it through peoples [sic] heads that a story is made out of an emotion or an excitement, and is not made out of the legs and arms and faces of one’s friends or acquaintances. Two Friends, for instance, was not really made out of your father and Mr. Richardson; it was made out of an effect they produced on a little girl who used to hang about them. The story, as I told you, is a picture; but it is not the picture of two men, but of a memory.

In his biography of Cather, James Woodress paraphrased thus: “In a…letter she explained…that it [“Two Friends”] was not really made out of the two friends at all but was just a memory. A story is made out of an emotion or an excitement and not out of the legs and arms and faces of one’s friends, she added.” The Cather scholar Susan Rosowski paraphrased the same letter thus: “As Cather explained privately, ‘Two Friends’ was not meant to be about the two men at all, but about a picture they conveyed to a child.” Neither of these versions gives the exact—and subtle—sense of what Cather was saying.

Another example of misleading paraphrase has been used as ammunition in the “Cather wars.” Cather had romantic “crushes” on her female school friends, fell deeply in love with a striking Pittsburgh girl, Isabelle McClung, and, after Isabelle’s marriage, spent much of her life with a devoted companion (and Cather’s first biographer), Edith Lewis. There are very few love letters in the Selected Letters, since Cather destroyed all her letters to Isabelle and seems hardly ever to have written to Edith. There is, though, one early letter to a young woman, Louise Pound, with whom Cather was clearly besotted when she was at school, a poignant, awkward mixture of showing off, desire to impress, and uncertain longing. It includes the sentence: “It is manifestly unfair that ‘feminine friendships’ should be unnatural, I agree with Miss De Pue that far.”

Advertisement

Sharon O’Brien, arguing in her 1987 biography that Cather felt her lesbianism was something shameful that had to be hidden, paraphrased this letter: “while it was unfair that feminine friendship should be unnatural, she nonetheless agreed with Miss De Pue that it was.” Joan Acocella, in her recent response to the Selected Letters, says that when she was questioning O’Brien’s line of argument about Cather as an unhappy and repressed lesbian, she looked up Cather’s original letter to Louise Pound, and paraphrased it thus in her own 2000 book: “It is clearly unjust that female friendship should be unnatural, I concur with Miss De Pue that far.” But because she could only paraphrase, Acocella felt she could not clinch her case against O’Brien, which was that she had based her whole story about Cather on a crucial misrepresentation of this early letter.

Scandals and secrets are not, however, what make this collection of letters interesting. In the absence of passionate love letters, the most painful and personal revelations are about Cather’s awkwardness as an imaginative, uncertain, ambitious teenage girl longing to get out of the rural Midwest, and her difficulties with her family—a neurotic, unsympathetic mother, a sister she didn’t like. Many of the people around her would become figures in her fiction, and it’s fascinating to see them referred to here, in the few youthful letters in the selection: the grandmother from Virginia who will be immortalized as “old Mrs. Harris,” or the welcoming, musical, Norwegian neighbor, Mrs. Miner, who will be the model for Mrs. Harling in My Ántonia. (The editorial policy is to let the letters speak for themselves, but the lack of annotation is often frustrating. Readers may need a biography with a family tree and a chronology to sit alongside this book.) But it took a long time for her early experiences to be shaped into writing.

Cather left Nebraska at twenty-two, in 1896, to work as a journalist and a teacher, first in Pittsburgh, then for McClure’s in New York. She only began to publish and be known as a novelist and short-story writer in her forties, by which time she was a woman looking back on her past and her childhood with deep feeling. She wanted to keep in touch with her family and the friends of her youth, but there was a growing distance—not just geographical, but emotional—between Red Cloud and her literary life in the East. Many of the letters longingly try to cross the bridge of time and distance, reminding her family and old Red Cloud friends of small details of their distant past, just as her novels and stories return to the places of her early life. “I cant endure the thought of going clear out of Roscoe and Douglass’s life,” she wrote to her friend the novelist Dorothy Canfield of her two brothers, whose deaths caused her great anguish, “and I want to keep alive all my feeling for them, whatever else I loose.”

Her anxiety about losing touch is a constant refrain. This is more than personal melancholy; it has to do with her work, its preoccupation with memory and return, and its balancing act between realism and sentiment. The letters show the shift from her sense of life in Nebraska in the late nineteenth century as harsh, ugly, narrow, provincial, and “grim” to her recognition of the epic, heroic quality of the lives of the pioneering European immigrants to the Midwest.

In her imagination, Cather was always revisiting her past. In life, she found it difficult to go back home, as she says in this letter to her brother Douglass in 1916:

I want to stay at home for a month or two, if it is agreeable to everybody, but I won’t stay after I begin to get on anyone’s nerves. I shall always be sorry that I went home last summer, because I seemed to get in [it?] wrong at every turn. It seems not to be anything that I do, in particular, but my personality in general, what I am and think and like and dislike, that you all find exasperating after a little while. I’m not so well pleased with myself, my dear boy, as you sometimes seem to think…. Be sure to meet me somewhere if you can. I think you’ll find me easier to get on with. Time is good for violent people.

The often turbulent relationship with her family parallels her mixed feelings for her natural subject, the landscape and people of the American Midwest and Southwest. There are vivid examples of this tension in these letters, common to writers—Mansfield, Joyce, Lawrence—who have left their home landscape behind them and then return to it compulsively in their writing. Here she is writing in 1912, from Arizona, to her dear friend, also a writer, Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant, while she is working on O Pioneers! It is sixteen years since she has left the Midwest for Pittsburgh and New York:

“Bigness” is the subject of my story. The West always paralyzes me a little. When I am away from it I remember only the tang on the tongue. But when I come back [I] always feel a little of the fright I felt when I was a child. I always feel afraid of losing something…. I never can entirely let myself go with the current; I always fight it just a little…. It is partly the feeling that there are so many miles—wait till you travel ’em!—between you and anything, and partly the fear that the everlasting wind may make you contented and put you to sleep. I used always to be sure that I’d never get out, that I would die in a cornfield. Now I know I will get out again, but I still get attacks of fright.

Where she “got out” to—newspaper offices in big eastern cities—is very fully illustrated here. We get a lively picture of her as a professional editor and writer in her twenties and thirties. She writes some tough letters to would-be contributors, and some proud letters about her own efficiency. To Roscoe, in 1910, she wrote:

From Sept. 1908 to Sept 1909, the first year that I have had charge of the magazine, we made sixty thousand dollars more than the year before. I say “we”; I don’t get any of the money, but I get a good deal of credit.

Watch for the March number, I’ve taken such pains with it.

In that context, we feel the full force of her decision, in her late thirties, under the influence of her journeys to the Southwest and the advice of Sarah Orne Jewett, to jump free at last of the day job and dedicate herself only to writing. The correspondence with Jewett is a well-known part of Cather’s story, but it is still moving to be able to read the 1908 letter to Jewett that describes how “deadening” and “diluted” and “superficial” her work in journalism makes her feel: “I feel all the time so dispossessed and bereft of myself.”

As her sense of confidence and her reputation as a writer strengthened, so her opinions and directives about how her work should be treated became more definite. She was given to emphatic pronouncements about her own work: “It’s the heat under the simple words that counts”; “I never did like stories much, and the older I grow the less they interest me.” From the huge success of My Ántonia in 1918, to the Pulitzer Prize for One of Ours in 1923, the ecstatic reception for Death Comes for the Archbishop in 1927, the big sales for her last novel Sapphira and the Slave Girl in 1940, and the endless anthologizing of late stories such as “Neighbour Rosicky,” Cather was, for over twenty years, one of the most admired and most read novelists in America.

She was extremely fastidious about how her work should reach her public. She was demanding from the start with Ferris Greenslet, her editor at Houghton Mifflin: “I think this book [O Pioneers!] ought to be pushed a good deal harder.” Much irritation was to come: “You’ve never given me a cover I’ve liked.” “I have to insist on an occasional use of the subjunctive mode, and the copy-reader belongs to that ferocious band who are out to exterminate it along with the brown-tailed moth.”

Eventually she left Greenslet for Knopf, whom she felt was much more sympathetic to her kind of work. She had a proper pride in her achievement. She complained about her trawl of honorary degrees and literary prizes as interruptions to her writing life, but she liked them, too. When she went to get a degree from Columbia University in 1928 she boasted to her mother, touchingly: “I really got a great deal more applause than any one else.”

She could be brusque and cross about modern America, its vulgarity, its advertising, its ridiculous creative writing classes: “Nothing whatever should be done to stimulate literary activity in America!” But not belonging was also an imperative for her: she deeply wanted to preserve the independence she needed to write her books. She wrote to Dorothy Canfield Fisher:

My familiar spirit is like an old wild turkey that forsakes a feeding ground as soon as it sees tracks of people—especially if the people are readers, book-buyers. It’s a crafty bird and it wants to go where there aint no readers.

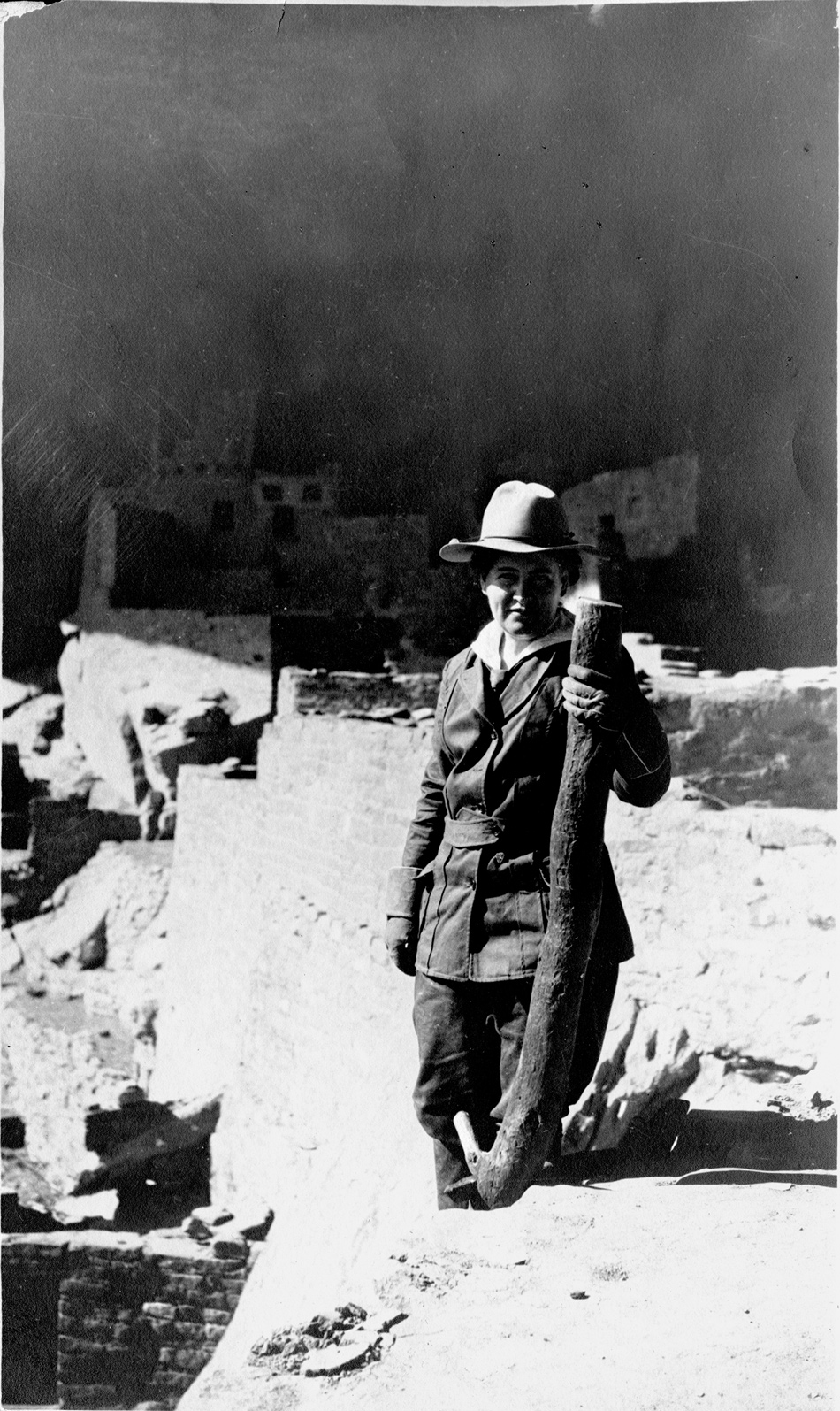

These are not witty, dramatic, especially stylish, or startlingly revealing letters. They are often taken up with details of family or professional business of interest only to Cather devotees. But they are absorbing, and often moving, because they show, over and over again, what matters to her. They are concerned with an extraordinary range of people, from the Bohemian women farmers of Red Cloud or the Mexicans in the Arizona railway towns to Tomáš Masaryk, president of Czechoslovakia, or the young Yehudi Menuhin. They are full of her passions: for Housman’s poetry and his English Shropshire landscape, for Robert Frost, for Paris and Provence and Italy, for the big Nordic Wagnerian opera singer Olive Fremstad, for the soft rolling Nebraskan landscape of her childhood, above all for the country of the Southwest, the mesas and the deserts, where she placed some of The Song of the Lark, the central part of The Professor’s House, and Death Comes for the Archbishop: “a country that drives you crazy with delight.”

She is a writer who took a long time to find her way but who, once she started, knew exactly what she wanted to do and how to do it. There are some misunderstandings about her own writing. She is sentimentally overattached to her war novel, One of Ours, and rates it more highly than she should; she thinks better of The Song of the Lark than anyone else, because it has so much personal feeling in it. But mostly she knows what she is doing, and how and why—for instance in this sentence to an old Red Cloud friend about The Professor’s House: “It was such a satisfaction to me to have you read [the book], dear Irene, and to see that you got at once the really fierce feeling that lies behind the rather dry and impersonal manner of the telling.” Or here, to Alfred Knopf, of A Lost Lady:

It’s a little, lawless un-machine made thing—not very good construction, but the woman lives—that’s all I want. I don’t care about the frame work—I’ll make any kind of net that will get, and hold, her alive.

The letters show her concern for authenticity, for creating real figures, for shaping memory into imaginative art, for classical austerity, and for a transparency of language. Every so often the voice of the books, that wonderful voice that mixes rigor and tenderness, harshness and longing, precision and breadth, comes through in these emphatic, practical letters. Here she is writing in 1927, to her English friend Stephen Tennant, harking back to her essay “The Novel Démeublé” of 1922, where she wrote about the need to empty the fictional room of furniture and aim at simplicity:

Nearly all my books are made out of old experiences that have had time to season. Memory keeps what is essential and lets the rest go. I am always afraid of writing too much—of making stories that are like rooms full of things and people, with not enough air in them.

And here she writes to a very old Red Cloud friend, Carrie Miner Sherwood, in 1934, about My Ántonia, speaking of the anecdote that inspired the suicide of Mr. Shimerda in the novel:

As for Antonia, she is really just a figure upon which other things hang. She is the embodiment of all my feeling about those early emigrants in the prairie country. The first thing I heard of when I got to Nebraska at the age of eight was old Mr. Sadalaak’s suicide, which had happened some years before. It made a great impression on me. People never stopped telling the details. I suppose from that time I was destined to write Antonia if I ever wrote anything at all.

She is echoing the voice of her narrator Jim Burden, who ends his story with these melancholy, elegiac, consoling words:

For Ántonia and for me, this had been the road of Destiny; had taken us to those early accidents of fortune which predetermined for us all that we can ever be. Now I understood that the same road was to bring us together again. Whatever we had missed, we possessed together the precious, the incommunicable past.

This Issue

July 11, 2013

A Pianist’s A–V

Hard on Obama

The Unbearable