My Brazilian friend Marina and I were picking up a visiting friend from New York, who heads an NGO, in her hotel lobby near Paulista, the most prestigious avenue in São Paulo. It was 7:30 on a busy Friday night last October.

We walked up to a taxi outside the hotel. I sat in the front to let the two women chat in the back. Marina asked me to Google the restaurant menu. I was doing so when I saw a teenage boy run up to the taxi and gesticulate through my open window. I thought he was a beggar, asking for money. Then I saw the gun, going from my head to the cell phone.

“Just give him the phone,” Marina said from the back seat.

I gave him the phone. He didn’t go away.

“Dinheiro, dinheiro!”

I didn’t want to give him my wallet. The boy was shouting obscenities. “Dinheiro, dinheiro!”

The boy’s body suddenly jerked back, as a man’s arm around his neck pulled him off his feet. The man, dressed in a black shirt, was shouting; he had jumped the boy from behind. He started hitting the boy. The taxi driver sitting next to me was stoic. He said that this had never happened to him before, but he couldn’t have been more blasé.

The next thing I saw was the boy and another teenager, probably his accomplice, running away fast up the street. The man in the black shirt chased them a bit, then came back panting to the taxi. “Did the bastard get anything?” our savior, whom we later nicknamed Batman, asked. He wasn’t a plainclothes cop, as I’d originally thought; he was just an ordinary citizen who was tired of the criminals.

“A phone,” Marina responded.

“Sons of whores. These motherfuckers—they always come in twos. Cowards.”

The taxi driver drove us to the nearest police station. Two lethargic cops were the only people there. “We get ten of these a day, just in this precinct,” said one of them.

The other cop went over to check in his register. “Three before you today.” There are 319 armed robberies a day in São Paulo.

Everyone in this country has a story. Priscilla, whom I met the next day, has been robbed ten times. Once a kid held a piece of glass from a broken bottle to her neck. Another time she was in a home invaded by gunmen, and one of them held a gun to her head for forty minutes.

I had gotten off lightly—just my phone taken. I still had my wallet, thanks to Batman, and I wasn’t beaten or killed or kidnapped.

The cities of Brazil are some of the most violent places in the world today. More people are murdered in Brazil than in almost any other country. In 2010, there were 40,974 murders there—21 per 100,000 inhabitants, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), compared to the global rate of 6.9. The highest number of murders was in India, at 41,726. But India has a population six times bigger than Brazil’s, so its murder rate is only 3.4 per 100,000 inhabitants. (Italy, by comparison, had 529 murders that year, at a rate of 0.9.) Four Brazilian cities had a murder rate of over 100 per 100,000 residents. Between 5 percent to 8 percent of Brazilian homicides are solved—as compared to 65 percent of US murders and 90 percent of British murders. Most of the victims are male and poor, between fifteen and just shy of thirty. The homicide rate has shaved seven years off the life expectancy in the Rio favelas (slums).

And this year another form of violence started making the headlines, with several high-profile cases of rape in Rio, including that of an American woman in a moving public bus. Rapes in the city increased 24 percent last year, to 1,972 reported cases. Sociologists and police officials are at a loss to explain this trend in a country where women are free to dress as they please, whose laws are often held up as a model for combatting gender violence, and whose president, Dilma Rousseff, is a woman.

The violence done to humans parallels the violence visited on the environment. In the great swath of greenery that makes up a large part of the country, fires, logging, and ambitious agribusiness schemes continue to devastate the rainforest, in spite of—or perhaps because of—Rousseff’s changes in the forestry code first formulated in 1965. According to government figures, deforestation, which had declined by 84 percent in the eight years before August 2012, has shown a 35 percent increase since then.

The violence hasn’t prevented Brazil from emerging on the world stage as the preeminent country in Latin America. Next year, it will host the World Cup; two years after that, the Olympics. Between 2003 and 2011, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—“Lula”—Brazil’s remarkable president, brought about one reform after another that improved the country’s economy. Rousseff, his successor, was until the protests of this June favored to win a second term next year. Both she and Lula are from the center-left Workers’ Party. Now, while not growing as fast as it did in the days before the crisis of 2008, the economy is still the world’s seventh largest. Brazil in the 1950s was 85 percent rural and 15 percent urban. Today the figures are reversed: the country is 87 percent urban. It’s the fastest urbanization of any country in recent times.

Advertisement

Brazil is also a model for other developing countries looking to help the poorest of their citizens. “Bolsa Família” (family allowance), introduced by Lula in 2003, is a startlingly successful program in which the government pays small amounts of cash directly to poor families. Some of the benefits are tied to certain conditions that the recipients must meet, such as making sure their children attend school. It covers a quarter of all Brazilians, 50 million people. This has led to a 20 percent drop in income inequality in Brazil since 2001, when it was one of the most unequal countries on the planet. Thanks to Bolsa Família, Brazil’s middle class grew from 40 million to 105 million in the last ten years. This has created the world’s biggest lower-middle class.

Revolutions generally begin with the formation of a middle class, as recent events demonstrate. In June, protests in São Paulo over a ten-cent increase in bus fares swelled into the largest demonstrations since the fall of the dictatorship, drawing millions of people into the streets of all the major cities. They were protesting the lavish outlays on the World Cup and other sporting events at the expense of basic facilities for transport and education; endemic corruption in the Workers’ Party; the slowdown in the economy; and the high levels of violence in Brazilian society. Most of the protesters were young, college-educated, and unaffiliated with any political party.

The government tried hard to respond to the demonstrators’ wide-ranging grievances. The mayors of São Paulo and Rio rolled back the bus fares. Dilma Rousseff promised a referendum on a package of reforms including a shift from proportional representation to voting by district, which could mean more responsive governance in the favelas. The demonstrators, some of whom seek an outright cancellation of the World Cup, do not so far seem to be satisfied. Rousseff’s approval rating plunged from 57 percent in early June to 30 percent a month later.

The anger of the demonstrators arose partly from injustices that have persisted throughout Brazil’s history. Bolsa Família has done much to solve the problem of inequality, but not race. Half of the country is black, but blacks make up 70 percent of the poorest Brazilians. According to studies based on the 2000 census, an eighteen-year-old white Brazilian boy has, on the average, 2.3 years more education than an eighteen-year-old black boy. The father of a white boy also had 2.3 years more education than the father of a black boy. Sixty years ago, the grandfather of a white boy had 2.4 years more education. Practically everything else in the country has changed, but the educational disparity between white and black has remained stubbornly constant over three generations.

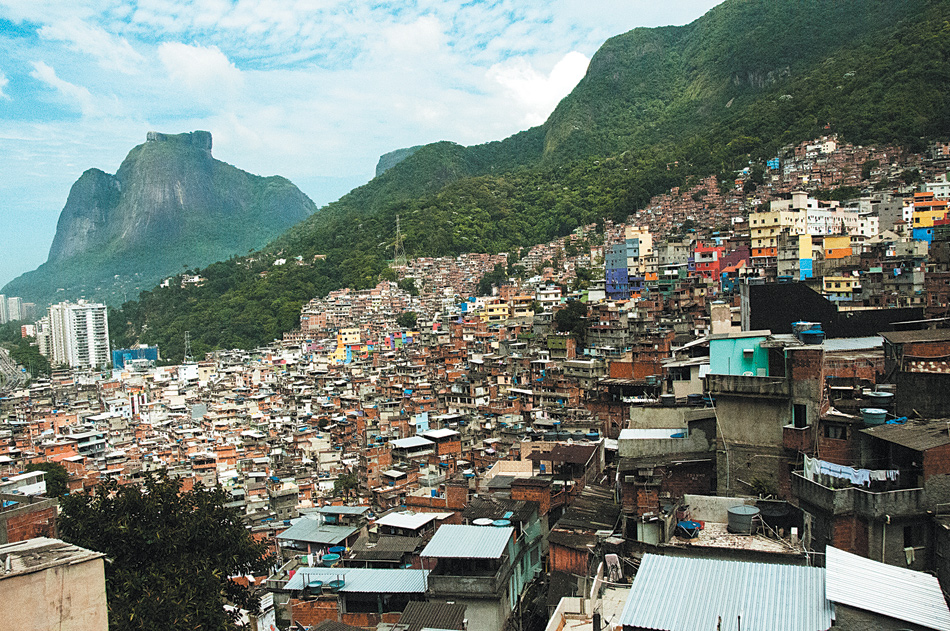

Brazilians like to think of themselves as a multiracial society, but a walk around the favelas of the cities demolishes this myth. Most of the residents are dark-complexioned, much darker than most of the rich who live by the water or in the suburbs, and darker than most of the young people who have recently been protesting in the streets. Over the last year and a half, I have been visiting São Paulo and, especially, Rio de Janeiro, observing the process of “pacification,” by which the government attempts to peacefully enter and reestablish state control over the most violent enclaves of the city, those dominated by drug gangs called traficantes, or by syndicates of corrupt police called militias. Until 2008, when the pacification program started, the traficantes controlled roughly half of the favelas, and the militias the other half. Both still hold power in most favelas. The ultimate aim of the state government of Rio’s plan, called the Unidade de Polícia Pacificadora (UPP), or Police Pacification Unit, is to drive both of these groups out and replace them by the state.

Today, of Rio’s 6.3 million people, 1.4 million live in the favelas. There are some 630 of them, containing more than a thousand “communities.” The state government aims to “pacify” forty of these favelas by the time of the World Cup next year—a kind of demonstration effect that will get attention from visitors. Since the program started in 2008, thirty of the largest have been pacified—that is, they are under the control of the official police forces, not the drug dealers or the militias. In the past, the police would raid individual favelas, capture or kill the biggest drug dealers, and leave. They would soon be replaced by other dealers, and the violence would continue. “The new strategy is not to target individual drug dealers. It is to take back territory,” a high police official told me.

Advertisement

Under the UPP program, elite police units—and in some cases troops from the army and even the navy—invade the favelas and stay for up to three months. Then they are replaced by the regular police and squads of UPP civil servants. The UPP establishes schools and garbage collection, brings in public and private companies to provide utilities such as electricity and television, and hands out legal documents such as employment and residency certificates. In the areas under its control, the UPP has set up community security councils, which attempt to mediate conflicts between local hotheads before they spread. The message is: the state is here to stay. So far, the program has generally been seen as a success, and was a major factor in the reelection of Sérgio Cabral in 2010 as the state governor backed by the Workers’ Party.

One night in Rio, Walter Mesquita, a street photographer, took me to a baile funk, a street party organized by the drug dealers, in the unpacified favela of Arará. It was an extraordinary scene: at midnight, the traficantes had cordoned off many blocks, turning the favela into a giant open-air nightclub. One end of the street was a giant wall of dozens of loudspeakers, booming songs and stories about cop-killing and underage sex. Teenagers walked around carrying AK-47s; prepubescent girls inhaled drugs and danced. On some corners, cocaine was being sold out of large plastic bags. Everybody danced: grandmothers danced, children danced, I danced. It went on until eight in the morning.

Although such parties are officially prohibited in the pacified favelas because of their multiple breaches of the law, ranging from noise violations to exhortations to murder—even the music played there is called baile funk proibidão—the state and its forces were nowhere to be seen. The rival gangs were a bigger threat than the police. The three gangs that control much of Rio have remained more or less stable for the last couple of decades: the Red Command, the Third Command, and Friends of Friends. According to a top police official I spoke to, in a city of just over six million there are some thirty to forty thousand people in the gangs.

The day after the baile funk, I was flying in a police helicopter over Rio. It took us over Ipanema, a beach for the well-to-do, and the newly pacified favela of Rocinha. I asked if we could fly over Arará. The pilot pointed it out in the distance, and said he could not fly directly over it. He was concerned about getting shot down. A couple of years ago, the traficantes had brought down a police helicopter with antiaircraft guns. So the police cannot safely enter a large part of Rio by land or by air. This, too, is the future of many megacities in the developing world, from Nairobi to Caracas. There is a de facto sharing of power between the legitimate organs of the state and the gangs, the militias. Many people will die as the exact contours of this power-sharing are negotiated.

My friend Luiz Eduardo Soares told me a story about power in the favelas. He is an anthropologist who was the national secretary for public security in 2003. He also wrote the book Elite da Tropa (Elite Squad), a study of police brutality and corruption that was made into the most popular film in the history of Brazilian cinema. He made many enemies among corrupt politicians and police. In 2000, security forces found detailed plans to kill Luiz and his daughters—there were notes on when and where they would be going to school, and at what times. The planners were corrupt police officers. Luiz had to flee with his family, first to the US, and then when he returned to Brazil, to a state in the south of the country.

One night Luiz had a call from a man named Lulu, one of the top traficantes in Rio. Lulu was now old for the drug trade—in his thirties. He wanted to surrender; he wanted to give up the gangs and live to see his children grow up.

Luiz said that if Lulu came to see him he’d have to arrest him. Then he would be put away in a jail like Carandiru, where after a 1992 riot the police opened the gates and sprayed the inmates with gunfire, massacring 111 of them. Luiz hoped for the best for Lulu, but his prospects did not seem good. He was wanted both by the police and by rival gangs.

A little later, Luiz was in the far north of the country, in a traditional temple where they worship old gods, the ones who were here before the Portuguese. Luiz was praying when he felt a tap on his shoulder. He turned around and saw Lulu smiling at him.

“What are you doing here?” Luiz asked.

“I’m here to see my mother. I got away.”

Soon after that meeting, the Rio police found Lulu. It was stupid of him: the first place a wanted man runs to is his mother. Men came up in a jeep and, without arresting him, took him back to Rio, to his favela, to the police station.

According to Luiz, the chief of the local police appealed to Lulu: “We want you back. It’s been hell since you left. You kept the peace among the gangs. And besides, I need your money for my political campaigns. You have to get back to work, or else.”

So Lulu went back to work, selling coke and meth to the rich kids in the nightclubs of Copacabana and Ipanema. But he had tried to break away; the boys on the corner didn’t trust him, didn’t respect him as they used to. He couldn’t make the 300,000 reais the cops demanded each week.

So one day they came again for Lulu. The cops, Luiz told me, sat him down in a stone chair in an open area of the slum and, with the whole favela watching, shot him in the head. He was useful to the police only when he had power to share. Powerless, he was dead.

Mário Sérgio Duarte is the high police official who led the invasion of Alemão, one of the largest and most dangerous favelas in Rio. In an eight-day operation in 2010, the police found more than five hundred guns: 106 carbines, rocket launchers, bazookas, thirty-nine Browning antiaircraft guns.

“Pacification started with me,” he tells me in the bar at the top of my hotel. Duarte’s mother was a seamstress; his father was murdered in 1972 over a “personal dispute.” Duarte studied physics in college, but chose to join the police force. His T-shirt says, “Listen as your day unfolds.”

In the 1980s, cocaine started coming into the favelas from Colombia and Bolivia, accompanied by Eastern European AK-47s from Paraguay. A carbine, such as an AK-47 or M-15, now costs around fifteen or twenty thousand reais—$7,500 to $10,000. The traficantes have rocket launchers now, says Duarte, “better weapons than the police,” who have .38s and 9-millimeter revolvers. Each year, some fifty cops and around 1,500 traffickers are killed. Last year, over a hundred police in São Paulo were murdered by the drug dealers, and police promised to kill five “bad guys” for every cop killed.

The drug trade in just one favela, Rocinha, Duarte tells me, runs to around a million reais per week. But it’s not just drugs. The dealers run a parallel economy in pirated cable TV, phones, and moto taxis, and have their own systems of justice.

“We don’t expect drugs to be stopped, just the violence with the drugs,” Duarte says. The drugs these days are ecstasy, PCP, and crystal meth, coming in from Europe. He points to Santa Marta as an example of a pacified favela where drugs are still traded, but there are no visible weapons, “no king of the hill.”

The state government has increased the armed police force in Rio from 36,000 to 42,000, toward a target of 50,000. (Another 10,000 are in the “civilian police,” who don’t wear uniforms and don’t carry official weapons.) Their salaries start at 1,500 reais per month, and in six years go up to 1,900 reais. A policeman stationed in a pacified area gets another five hundred a month to help him fight the temptation to take bribes or join one of the violent syndicates—the militias—run by corrupt police.

Duarte calls the militias “the rotten product of the official order.” There are a couple thousand policemen in the militias, he estimates, along with firefighters and ex-soldiers. They started…

“…from 2006!” a waiter from Rocinha who has been listening while getting our drinks chimes in.

The militias don’t allow drug dealing by the traficantes, but they make money in protection, cable TV, transportation, loan sharking. “A trafficker is hell, a militia is purgatory,” Duarte says. The militias create unwritten, though widely obeyed, rules for neighborhoods: you can’t leave your home after a certain time; if you rape women, you’ll be killed publicly in a ceremony. Your radio can’t be too loud. The punishment is often torture or the death penalty. The militias sell arms to traffickers; they deal drugs when necessary; they employ guards who are former traffickers expelled from gangs.

The enemies of the militias are the elite police squad, the BOPE, created during the dictatorship to fight Marxists but then retrained for pacification. (BOPE stands for Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais, or Special Police Operation Battalion—the unit featured in Soares’s book Elite Squad.) Duarte, who led the BOPE for a time, had to try to convince the government that there was a distinctive kind of conflict in Rio: “not ethnic, not religious, not Marxist.” He likes to quote Plato and Hegel in casual conversation. When I later mentioned to a BOPE sergeant that I’d met Duarte, he said, with a mocking laugh, “Ah, the philosopher.”

Along with Marina, I went to meet some “bad guys” in the Parque União subdivision of the Maré favela complex by the port. Two of them meet us in an open-air bar, a twenty-one-year-old ex-traficante and a handsome young man of the same age who sings in a nightclub and acts as the master of ceremonies there. The drug dealer has a tattoo on his right forearm that reads “Emilly.” “Minha filha,” he explains—his daughter. She is seven years old, and he doesn’t want her to go to the baile funk where he picks up his women. “I would like my daughter to escape the statistics.”

When he was active in the gang, he killed people in gunfights, and doesn’t feel bad about it. “At that moment, I can’t afford to think, he might be a father just like me. I’d rather have his mother’s tears falling on his grave than my mother’s on mine.” He’s also been involved in robberies in the rich parts of Rio. After the robberies, he and his gang hijack a series of cars until they get safely back to the favela. He never robs in the favela. Only someone who’s on crack will rob here. This explains why I feel safer here than I did the previous night on the beach in Ipanema.

When the favela wants to have a baile, people steal two buses from the yard across Avenida Brasil and block off the street with them. At the baile they may hear about someone who will be killed by the end of the evening—someone who’s insulted the “owner of the favela”—the top traficante.

The two young men insist on escorting us to our van on the highway. At one point, there are three white metal bollards implanted into the road, turning it effectively into a pedestrian zone. “That’s for BOPE,” the trafficker explains. The police cars will find a surprise when they try to invade.

Their favela, they say, is to be pacified by the end of the week. It’s not that the young traffickers lack alternatives for employment, such as in Rio’s booming tourist industry. It’s that they won’t have the same level of luxury: “a gold chain as broad as a baby’s arm.”

The BOPE did invade the Maré complex—but not as part of the UPP process. During the June protests, robbers from the favela started looting shops along the Avenida Brasil. The BOPE was called in, and a sergeant chasing the robbers into the favela was shot dead. His colleagues erupted. By the time the smoke died down, eight residents of the favela—some of them young traficantes just like the one I had recently interviewed, others merely innocent bystanders—had been killed.

What is happening in the favelas of Rio is not so much pacification as legalization. The dictatorship that ruled from 1964 to 1985 was brought down after many years and great sacrifices. Everyone who was not connected to the junta was its victim. People rushed to spend their pay as soon as they got it in their hands, because by the afternoon it would be worth much less. When democracy came, everybody—the rich in Leblon and the poor in Rocinha—felt they should benefit from it, and in Brazil, for a time, most people did.

But in the favelas there was no democracy. The traffickers continued with their own dictatorship; the people of the favela still had great trouble getting access to the courts or casting a vote. Pacification is an attempt to interrupt a despotic process. It is, for the construction workers and ladies who sell feijoada—a black bean stew—in the slum, the final fall of the dictatorship.

During the last twenty years, the drug dealers took informal control of much of life in the favelas, including, most importantly, music, the cultural lifeblood of Brazil. “Our challenge is what will happen after the pacification,” I was told by Ricardo Henriques, who was until last year the head of the Instituto Pereira Passos, the government’s urban think tank that formulates policy for the UPP.

As Henriques rather optimistically sees it, the takeover of the favelas will happen in three phases. The first consists of the police moving in and denying the drug dealers the ability to do what they want, legally and culturally. The second: “It’s a little bit boring, the police are here.” The third phase consists of the state substituting for the prohibited culture an officially sanctioned culture, or at least culture that doesn’t continue to glorify rape and murder. “You do it in a creative manner,” explained Henriques. “No guns. Less erotic, but really creative. The music is not proibidão.”

For decades, the favelas have existed in a parallel system to the rest of Brazil. “The idea of the state is to stay there for the long, long term,” Henriques said. He wants to reduce the inequality between the favela and the rest of the city. “Our challenge is to integrate those areas into the city.”

If this schematic-sounding vision of pacification works—and the ongoing protests throughout the country are putting it in doubt—what would come after it? One night I went to a jazz club in the favela of Tavares Bastos, which had been pacified for a year, right below the headquarters of the BOPE. The rooms of the club were packed with sweaty bodies and heavy with marijuana smoke. If the BOPE wanted to find drugs it wouldn’t have to go far. But it will never come here, because these are people from the rich, white areas of Ipanema and Leblon. The only black people I could see were the saxophonist and my guide, the street photographer, who lived here.

“The people from the favelas can’t imagine themselves here,” said the photographer. The music was bebop and bossa nova, an American idea of the jazz that Brazilians listen to. No samba here, much less funk.

The club was opened five years ago. A beautiful white economist who works for a bank, wearing an expensive dress, told me she was already bored. “Two years ago there used to be more interesting people. Now I only see all the people I would see near the beaches.”

It costs fifty reais to get in; a beer is fifteen reais. On the way to the club, I passed a number of small cafés. In some, neighbors were enjoying beers that cost a third as much. In one, pleasantly overweight couples were dancing close together to samba. All the lights in the houses of the favela were out; it was after midnight. But the white patrons on their way to the jazz club were raucous, laughing, energized by the thrill of the expedition to this clandestine destination.

In Tavares Bastos, and in favelas like Cantagalo, with its easy access to the rich southern zone of Rio and increased security after the pacification, the residents are being forced out, not by violence, which they can live with, but by high rents, which will make living there impossible. Their right to live there was protected as long as it was illegal. After pacification, the biggest threat to longtime residents of the Rio favelas will come not from drug dealers, but from property dealers.

—July 11, 2013