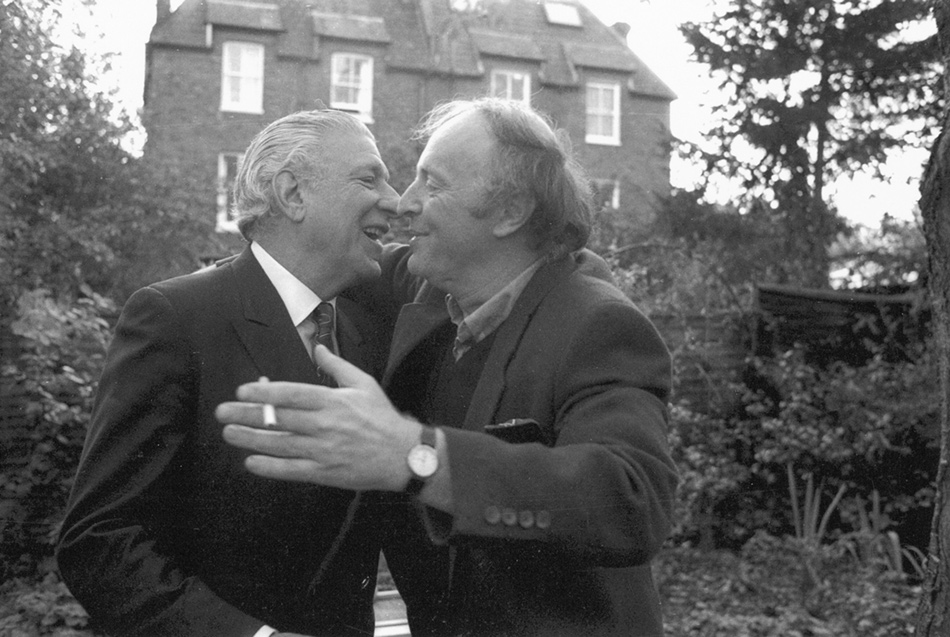

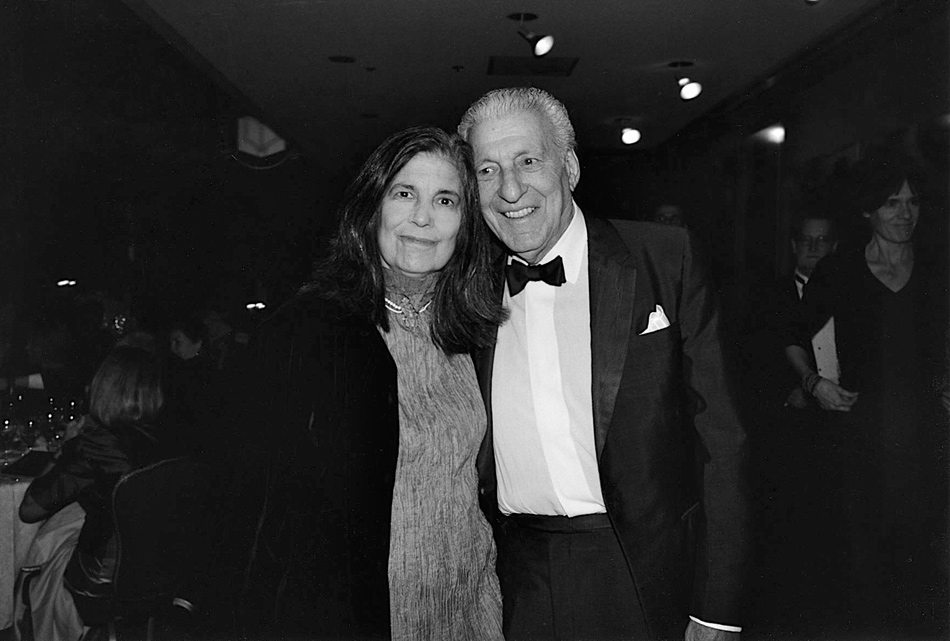

Boris Kachka’s history of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, the distinguished publishing house that the late Roger Straus founded in 1945 and ran on a shoestring brilliantly until his death in 2004, is gossip at a very high level: not quite the level of art achieved by Dickens and Proust, who fictionalized their characters, but all the more gripping for being real and meticulously footnoted. I was a decade younger than Roger, a friend for many years, admirer, and occasional rival. Kachka’s Roger is the ebullient, often coarse, actually gentle curator of first-rate talent whom I knew, admired, and liked. For authors, editors, and publishers Hothouse will be catnip for its revelation of the firm’s affairs in both senses: an employee famously said that “tennis is to Scribner’s as sex is to Farrar, Straus.” Roger’s loyal, worldly, forgiving wife Dorothea called the office a “sexual sewer,” and confined her marital role to their handsome town house whose literary evenings were legendary. Roger and Dorothea occupied separate bedrooms.

Readers will be no less fascinated by Kachka’s account of FSG’s dealings with Tom Wolfe, Flannery O’Connor, Philip Roth, Edmund Wilson, Joan Didion, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Bernard Malamud, John McPhee, Susan Sontag, T.S. Eliot, Seamus Heaney, Pablo Neruda, Carlos Fuentes, Robert Lowell, Scott Turow, Jonathan Franzen, Jeffrey Eugenides, and Thomas Friedman among many other FSG authors. The cleverly titled Hothouse is Pepys for our time, an unblinking account of publishing history as it was made by Roger’s firm, the last of America’s major independent publishing houses. Roger would have been thrilled to publish this fine book, including its frequent and deserved criticisms of himself.

Roger’s small, gemlike firm published twenty-five Nobel Prize winners during his fifty-eight-year tenure as founder and president, a breathtaking achievement. He was the last of the great Jewish book publishers whose taste, courage, and energy defined American book publishing for nearly a century as the traditional houses withered away. The first of these pioneers was the profligate genius Horace Liveright, who in the 1920s published The Waste Land, Dreiser’s American Tragedy, Hart Crane, Eugene O’Neill, the early work of Hemingway and Faulkner, and the Modern Library series which introduced three generations of Americans to world literature. His instinct for quality and his libido prefigured Roger’s but he lacked Roger’s iron will to survive.

Liveright, assisted by showgirls and champagne, elevated self-destruction to an art. He lost his company to his rapacious accountant, the odious Arthur Pell, who literally threw him out of the office. He died broke at forty-nine. But his editorial brilliance compounded with his bold marketing panache created a formula and style for his prudent successors—Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer at Random House, Alfred and Blanche Knopf, Dick Simon and Max Schuster at Simon and Schuster, and Harold Guinzburg at Viking, whose firms defined the book-publishing century. Roger published his first catalog in 1946, thirteen years after Liveright’s death, by which time the Liveright editorial and promotional style was well established.

The great houses founded by these publishers exist now as relics of their former selves under conglomerate ownership. Roger’s FSG, the last to fall, maintained its independence until 1994 when an overconcentrated retail market, alternative media, and the high-risk care and feeding of big-name authors made further resistance unwise. Roger at seventy-seven sold his precious firm to Holtzbrinck, the smaller of the two German conglomerates that now dominate American book publishing. Random House, which had acquired Knopf, Pantheon, and several lesser imprints, might have assembled a conglomerate of its own as other firms faltered, but its owner chose not to. Wall Street also passed. One wonders how American book publishing would have survived had Bertelsmann, the larger German conglomerate, not picked up the pieces. One might also wonder whether economies of scale assure the survival of the conglomerates themselves as alternative media proliferate, and the environment becomes increasingly digital while book publishers alone among media industries cling to their obsolete analog infrastructure.

The United States, and indeed the world, without a viable book industry and leaders like Roger Straus to energize it is awful to contemplate. Within a bookless generation, or two, or three, human beings would have lost the better part of the knowledge acquired by their species over millennia, from making an omelette to parsing the universe and removing an appendix. Roger was a brilliant businessman dealing with skill and passion in a product of marginal financial value but of limitless value in itself. In the digital future, who will be his successors?

Roger was born in 1917 to Roger Williams Straus, whose millionaire father served under Theodore Roosevelt as the first Jewish member of a presidential cabinet, and to Gladys Guggenheim, the daughter of the paterfamilias of America’s wealthiest Jewish dynasty. Mrs. Roosevelt and the Andrew Carnegies attended the wedding. Roger junior was born three years later. His family and that of his wife Dorothea, heiress to the Rheingold brewing fortune, together with his Manhattan town house, his Westchester estate, and his tan Mercedes convertible, generated an aura of great wealth, but while Roger was hardly penniless he was far from rich, the family fortunes having eroded.

Advertisement

He launched his firm in 1945 with modest investments from family and friends, and while other publishers occupied modern midtown offices Roger never left his cramped, downtown warren above seedy Union Square where it was said, though not reported in this book, that on hot summer days he distributed ice cream bars to his sweltering staff rather than invest in air conditioning. The new firm got off the ground thanks to a best seller by a quack nutritionist. Roger published a sequel that sold poorly and largely shunned such opportunistic publishing thereafter. Roger for all his macho posturing had the refined instincts of Duveen and ran his company accordingly.

The publishing of general fiction and nonfiction—so-called trade book publishing—as opposed to textbook and other forms of specialty publishing has never interested Wall Street, which sees book publishing as a rich man’s hobby, a hand-to-mouth business like the theater, which also recreates itself from one season to the next. Trade book publishers have typically financed their firms from their own funds, from company earnings, and in lean years from the kindness of friendly banks—in Roger’s case the US Trust, where remnants of his family’s depleted fortunes were on deposit.

Roger and his rivals did not expect to make a fortune—the fathers and grandfathers of some of them did that for them. Their goal was to discover and encourage editors who could discover and cultivate important authors, and occasionally land a number-one best seller or a major book award or in Roger’s case yet another Nobel Prize. Roger was a ferocious competitor but not at the expense of his literary standards. With few exceptions, he published authors he admired and was flattered by their friendship in return. Roger lacked the skills and patience to be his own editor in chief, but his taste defined the firm. His nose for quality was exquisite. His persona was anything but. His language was often indelicate. He would refer to his many distinguished Italian writers with a coarse epithet. He affected silk ascots and fine tailoring but chose to portray himself as a mug even on the tennis court, where his play was all drops and slices.

This was a pose which evolved into a personality. Roger’s older brother Oscar breezed through St. Paul’s and Princeton and joined the family business after a term in the foreign service. Roger, who hated his brother, didn’t make it through secondary school and dropped out of Hamilton College, which had accepted him as a favor to the family. His response to these wounds was like that of Shakespeare’s warrior Coriolanus, who replied to the mob that exiled him, “I banish you. There is a world elsewhere.” I was never convinced by Roger’s persona and wondered what wound it concealed until Kachka explained it. The macho act was skin-deep. The Roger I knew was gentle. His enthusiasm for his writers was real. His favorite book was Memoirs of Hadrian by Marguerite Yourcenar. Some of his envious competitors thought it was the only one. They were wrong.

His choice of Bob Giroux as editor in chief was revealing. Bob came to FSG from Harcourt Brace, a distinguished literary firm that had deteriorated under philistine management. He was fastidious to a fault and brought with him a distinguished list of British and American poets and novelists including T.S. Eliot, as well as a highly refined literary sensibility and a mature grasp of fiscal reality, but he shunned the overt commercialism that increasingly characterized the industry. Roger could have had his choice of chief editors. That he chose Bob Giroux should have surprised nobody. To an interviewer Roger said:

Many people have accused me of being an elitist. I’m guilty. I am an elitist. I like good books…. A lot of publishing houses are being run by accountants, businessmen and lawyers with very little concern for books…they could just as well have been selling spaghetti [a reference to the Italian-American president of Random House at the time, whom Roger despised].

Roger and Giroux had met in the navy where Roger, then a desk-bound officer, worked for the Office of Public Information in charge of the Mag-azine and Book Section with offices on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue. There he was visited by Giroux, a lieutenant with a story to tell about action he had witnessed in the Pacific. Roger sold Giroux’s story to Colliers magazine for $1,000 and the relationship took hold.

Advertisement

Kachka writes somewhat unfairly:

Having seen Knopf sell out,* and knowing that Random House [where I was editorial director for three decades] and others were in full-on expansion mode, he had already decided to hew a middle course—to stave off acquisition by the big fish not by becoming one, which was probably impossible anyway, but by getting a little bit bigger and prettier. He believed, not unreasonably—though not entirely correctly, that Random House and its ilk would go the way of Harcourt, Brace and Houghton Mifflin, driving away quality in their dogged pursuit of the bottom line. Those authors would want to go somewhere smaller and more focused, somewhere with a reputation for treating writers with deference and dignity. And yet it wasn’t just care they needed, but feeding; FSG had to be big enough to afford them and stable enough to assure them, amid all the shake-ups, that they weren’t moving into a house of cards. FSG needed to scale up, without losing—to paraphrase a recent acquisition, John McPhee—a sense of what it was.

Roger relied on his authors to suggest additions to the FSG list. He especially depended on Susan Sontag, whose rarefied sensibility and reputation impressed him. Giroux, who may not have respected Susan’s judgment equally, was wary of the relationship. As Roger’s “first reader” on “many of the manuscripts that came [his] way…Sontag’s tastes, like her fiction, favored ideas and atmospheres over narrative,” Kachka writes somewhat opaquely—here and elsewhere an editor could have helped—arguing that it was “a preference that cost FSG at least one massive opportunity.” Roger had known of Umberto Eco but “deferred to Susan’s judgment on Eco’s new book, Il Nome della Rosa.” The company was having a bad year and could afford to publish only one of two recent Italian submissions. Susan urged him to do both. He resisted and asked her to choose. She chose the shorter book by an obscure Italian writer named Salvatore Satta. Susan “not only preferred it, she thought it would sell better. Eco had entire passages in Latin, after all.” Satta sold two thousand copies. The Name of the Rose became “one of the bestselling books of the century.”

Roger, bewitched by Susan, took the disaster in stride:

In 1982, while considering Eco, the company barely broke even, and then only with a little cash from the Strauses’ personal coffers. Had Farrar, Straus published Eco, the following year would have begun with a bonanza, instead of six months of frozen salaries.

Most publishers would be distraught by such a costly error. Some would have been frantic and discarded Susan but “Roger loved to tell the story of Eco vs. Satta, partly to show deference to Susan’s taste.” Here Kachka may be naive. Obviously Roger valued Susan’s taste as Giroux, and others, did not, and he was proud of their relationship; but for a cash-poor firm to lose a multimillion-copy title could have been catastrophic. Roger’s show of indifference was yet another bit of tough-guy bravado, an atypical indifference to the firm’s condition and the financial interests of his employees.

Roger was rumored to have been bewitched by more than Sontag’s intellect. Later the relationship cooled but Roger remained Sontag’s loyal and generous patron and publisher throughout her life. Years later when Sontag became a client of the famously aggressive agent Andrew Wylie, Roger’s dealings with Wylie assumed “all the permutations of a love triangle,” Kachka writes. Either he believed that Susan was favoring Wylie, whom she invited to dinner with an FSG author without either telling or inviting Roger, or conversely when Wylie didn’t support Susan after W.W. Norton published a biography of her that she found “extremely objectionable.” Roger demanded that Wylie end his representation of Starling Lawrence, Norton’s publisher, who was also a novelist under contract to FSG. When Wylie refused to abandon Lawrence, Roger imposed a six-month embargo on his agency, which the FSG staff secretly ignored. Roger also canceled FSG’s contract for Lawrence’s novel. By now Roger was in his eighties and becoming a caricature of himself but his obsession with Sontag remained even as the end was in sight. His obsession with quality was also evident when he hired as his successor and editor in chief Jonathan Galassi, a poet and scholar but someone more flexibly attuned to the current scene than the austere Giroux had been.

As I think of Roger now and his twenty-five Nobel Prizes and twenty-two Pulitzers and see the man behind his compensatory tough-guy mask, I see someone for whom books were more than articles of commerce. They were an obsession, a sacred trust, a kind of religion. He could have had his choice of family sinecures but he chose books. His glittering list of authors, his cartload of Nobels, distinguish him from all but a few of his contemporary publishers.

Roger died before the Gutenberg publishing technology that defined his generation became obsolete. He would not have welcomed digitization and could not have imagined his function in a world in which all books, old and new in all languages, are stored and delivered as digital files at virtually no unit cost for storage and delivery, and reproduced on demand wherever connectivity exists either on screens or printed one copy at a time in bookstores, libraries, schools, airports, and so on, and where success or failure is for the most part determined instantly by the Web, the ultimate word-of-mouth medium but where second and third chances are possible since nothing in cyberspace need be destroyed.

The future impact of this transformation from analog to digital is as indistinct to us now as the huge impact of Gutenberg’s printing press was to his contemporaries, including Gutenberg himself. As traditional book-publishing technology gives way to digitization, the fate of today’s conglomerates with their analog infrastructure and business model is open to question. Will they, can they adapt? Or will the new technologies displace them as Gutenberg’s press displaced the scriptoria of his day?

Roger would have resisted this transformation in which the Gutenberg mode assumes the character of a handicraft, but future Rogers will welcome the online challenge as new infrastructure creates new markets and new skills. As content is created, posted, and evaluated digitally from innumerable worldwide providers to multilingual billions of readers, publishers’ imprints will be indispensable marks of quality and relevance and there will be people like Roger to create and protect them. To regard books and their content reverently is human nature, otherwise how explain the persistence, millennium after millennium, of Homer and the horror we feel when books are burned, as if we ourselves were at stake? Since nothing need be lost in cyberspace, one may hope that Boris Kachka’s wonderful book and its hero survive digitally to inspire generations of online publishers as yet unborn.

This Issue

September 26, 2013

The American Jewish Cocoon

They’re Taking Over!

Stranglehold on Washington

-

*

Knopf was part of the Random House group, owned by Advance Publications, which eventually gave up and sold it to Bertelsmann. Bob Gottlieb, Knopf’s president and chief editor at the time, was a brilliant publisher and editor with impeccable taste, and needed no one to tell him how to run his business. ↩