Most of the electorate can’t be bothered with midterm elections, and this has had large consequences—none of them good—for our political system and our country. Voting for a president might be exciting or dutiful, worth troubling ourselves for. But the midterms, in which a varying number of governorships are up for election, as well as the entire House of Representatives and one third of the Senate, just don’t seem worth as much effort. Such inaction is a political act in itself, with major effects.

In the past ten elections, voter turnout for presidential contests—which requires a tremendous and expensive effort by the campaigns—has ranged from 51.7 to 61.6 percent, while for the midterms it’s been in the high thirties. Turnout was highest for the two midterms in which the Republicans made their greatest gains: in 1994, when Clinton was president, it was 41.1 percent and in 2010 it was 41.6 percent. In 2006, when Bush was president, the Democrats took over the House and Senate and won most of the governorships, turnout was the next highest, 40.4 percent. The quality of the candidates, the economy, and many unexpected issues of course determine the atmosphere of an election; but in the end turnout is almost always decisive.

The midterms, with their lower turnout, reward intensity. In 2010, the Republicans were sufficiently worked up about the new health care law and an old standby, “government spending,” particularly the stimulus bill, to drive them to the polls in far larger numbers than the Democrats. A slight upward tick in turnout numbers can have a disproportionate impact in Congress and many of the states, and therefore the country as a whole. The difference in turnout caused such a change in 2010; in fact, the Republicans gained sixty-three House seats and took control of both the governorships and the legislatures in twelve states; the Democrats ended up with control of the fewest state legislative bodies since 1946. The midterms go a long way toward explaining the dismaying spectacle in Washington today. State elections bear much of the responsibility for the near paralysis in Congress thus far this year and the extremism that has gripped the House Republicans and is oozing over into the Senate.

The difference in the turnouts for presidential and midterm elections means that there are now almost two different electorates. Typically, the midterm electorate is skewed toward the white and elderly. In 2010 the youth vote dropped a full 60 percent from 2008. Those who are disappointed with the president they helped elect two years earlier and decide to stay home have the same effect on an election as those who vote for the opposition candidate.

Little wonder, then, that there can be such a gulf between the president and Congress, particularly the House of Representatives—but also between the president and the governments of most of the twenty-four states over which the Republicans now maintain complete control; almost half of these were elected in 2010. Democrats have complete control over fourteen states. The Republican-controlled states include almost all the most populous ones outside of New York and California. Since the midterms of 2010 the Republicans in most of these states have pursued coordinated, highly regressive economic policies and a harsh social agenda. Thus, while there’s largely been stalemate in Washington, sweeping social and economic changes that are entirely at odds with how the country voted in the last presidential election have been taking place in Republican-controlled states.

As a result of the relative lack of interest in state elections, we now have the most polarized political system in modern American history. It’s also the least functional. Many state governments’ policies are not just almost completely divorced from what is going on at the federal level—but also in some cases what is prescribed by law and the Constitution. Systemic factors based in state politics explain more about our national political condition than tired arguments in Washington over who is at fault for what does or doesn’t—mainly doesn’t—happen at the federal level. The dysfunction begins in the states.

The 2010 elections were the single most important event leading up to the domination of the House by the Republican far right. Both the recession and organized agitation by the Tea Party over the newly passed health care law—“spontaneous” campaigns guided from Washington by the old pros Karl Rove and Dick Armey, and funded by reactionary business moguls—helped the Republicans, and especially the most radical elements in the party, sweep into the majority in the House of Representatives and take control of twelve additional states, including Ohio, Florida, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan. The Republicans who took over states in 2010 reset our politics. Among other things, they made the House of Representatives unrepresentative. In 2012 Democrats won more than 1.7 million more votes for the House than the Republicans did, but they picked up only eight seats. (This was the largest discrepancy between votes and the division of House seats since 1950.)

Advertisement

Thus, while Obama won 51.1 percent of the popular vote in 2012, as a result of the redistricting following 2010 the Republican House majority represents 47.5 percent as opposed to 48.8 percent for the Democrats, or a minority of the voters for the House in 2012. Take the example of the Ohio election: Obama won the state with 51 percent of the vote, but because of redistricting, its House delegation is 75 percent Republican and 25 percent Democratic.

The state government’s power over the redrawing of congressional districts every ten years is probably the single most determining factor of our political situation. It’s clear that the Republicans were successful in winning and using the 2010 elections as a prelude to the most distorted and partisan redistricting in modern times. Their approach was so different in degree as to be a difference in substance—and the post-2010 politics in Washington resemble nothing that has gone before. There has been something of a war raging among students of electoral politics over the role of redistricting in our current situation. But Sam Wang of Princeton, a neuroscientist who founded the Princeton Election Consortium, wrote in The New York Times earlier this year:

Political scientists have identified other factors that have influenced the relationship between votes and seats in the past. Concentration of voters in urban areas can, for example, limit how districts are drawn, creating a natural packing effect. But in 2012 the net effect of intentional gerrymandering was far larger than any one factor.

Moreover, the redistricting has become different from the process that we learned about in civics classes. Traditional “gerrymandering,” which had been practiced since the early 1800s, involved drawing weirdly shaped districts for the purpose of protecting incumbents. But in recent years redistricting has developed into a vicious fight for control of redistricting—though the shape of the districts can be just as weird.

The Republicans have made the greater effort to shape the House to their benefit, through a deliberate two-step process: first, win state elections so as to control the redistricting, and then redistrict to give the party as much advantage as possible in the House. Though they’ve done their own self-interested redistricting, Democrats haven’t been as zealous about controlling reapportionment. Still, through the combination of both parties’ actions, they have ended up with more safe seats than before.

There was just one problem: when the Republicans began their intense effort in the run-up to 2010 to take over state legislatures and draw districts free of serious Democratic challengers, they failed to anticipate that this would leave their members more vulnerable to challenges from the right. The fear of being defeated in local contests by even more radical Republicans has also taken hold in the state legislatures, which in turn affects the nature of the House. The more established House Republicans, including the leaders, now live in terror of a putsch from the most extreme right-wing elements of their caucus, in particular the Tea Party. They are not yet a majority of the party but they have the power to behave like one through their use of fear. A lamentable result of the effort to draw safe districts is that only an estimated thirty-five House seats out of 435 will actually be competitive in the 2014 election. Therein lies the source of the near paralysis of the federal government.

Nate Silver wrote in the The New York Times after the 2012 election that while there had been earlier periods of great partisanship, in particular between 1880 and 1920, “it is not clear that there have been other periods when individual members of the House had so little to deter them from highly partisan behavior.” Under these circumstances, it’s harder than ever before to put together bipartisan coalitions to pass major legislation, as had long been done for civil rights bills and other major changes in economic, social, and even environmental policy. The fact that Obama had to pass the health care law with almost no Republican support rendered it more vulnerable later. The Republicans’ limp and deceptive explanation for their opposition to the law is that the Democrats left them out of consideration of the bill (which was actually based on Republican ideas).

The Republicans who took over the states following the 2010 elections arrived with an agenda strongly based on model laws supplied by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), heavily funded by the Koch brothers along with some other big corporations. The other group that benefited most from the 2010 elections was the passionately anti-abortion Christian right—which is not only an essential part of the national Republican Party’s base but also dominates the Republican Party in about twenty states, and has a substantial influence in more than a dozen other state parties. The Christian right is tremendously effective in motivating its followers to go to the polls—and then threaten a loss of support if their agenda isn’t adopted.

Advertisement

The overall result of the new Republican domination has been that these states have cut taxes on the wealthy and corporations and moved toward a more comprehensive sales tax; slashed unemployment benefits; cut money for education and various public services; and sought to break the remaining power of the unions. Not only did Republican officials in these states manipulate the constitutionally guaranteed right to vote in their effort to win the presidency in 2012 and preserve their own power by keeping Democratic supporters from voting, but they are at it again. The constitutional right to abortion granted under Roe v. Wade has been flouted. The new strategy among anti-abortion forces is to limit legal abortions to the first twelve weeks of pregnancy. Several states have adopted this measure and others are in the process of doing so.

Pregnant women’s privacy has also been invaded through state measures requiring them to be subjected to transvaginal ultrasound examinations of the fetus, and forcing them to look at or hear described the result of any sonogram. Doctors have been ordered by state law to lie to women about supposed dire consequences of abortion, for example that abortions can lead to breast cancer. Abortion clinics in some states have been shut down or eliminated. Funding for other medical services for women, such as mammograms, has also been greatly reduced. Many of these state laws are under legal challenge and some of them may end up in the Supreme Court. Roe v. Wade may be doomed.

North Carolina provides the most dramatic example of what can happen to a state in just three years. It was formerly a progressive southern state, racially tolerant, and a proud leader in education. Obama carried North Carolina in 2008. But the Republicans won the legislature in 2010, and in 2012 they won the governorship. In addition, as a result of their redistricting after 2010, in 2012 they gained “super-majorities” in the legislature. Since then, the Republican governor and legislature have made drastic cuts in unemployment insurance and tax credits to low-income workers. The legislature is leaning toward passing proposals to reduce the number of teaching assistants and aid to college students, and it has cut the number of openings for children in state-run pre-kindergarten programs. Proposals are pending to flatten the income tax, expand the sales tax, and kill the estate tax.

The North Carolina legislature also passed a law to bar the courts from applying sharia law, making it the seventh state to do so. In reality, there’s no threat that courts will start interpreting the laws according to sharia doctrine, but Republican state lawmakers say they’re taking “preemptive” action. Oklahoma’s prohibition of sharia law was recently held unconstitutional by a federal court (as singling out a religion).

North Carolina has also adopted the most severe restrictions in the country both on abortion and on voting rights. It makes the impediments to voting that were used in 2012 seem meager by comparison. Its sole remaining abortion clinic is being shut down. North Carolina is one of the states that, as a result of the Supreme Court’s decision in June, was liberated from the requirement of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that it get prior clearance from the Justice Department before making changes in its voting laws. Texas and North Carolina, both under Republican control, were the first to savor their freedom by making it harder than ever for minorities, students, and the elderly poor to vote. A former North Carolina Democratic official said to me, “They do all these things and then they pass voting rights laws to keep us from voting them out of office.”

In 2014, thirty-six governorships, an unusually large number, will be up for election, including in such important swing states in presidential elections as Ohio, Wisconsin, Florida, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Until 2010, all of them but Florida were governed by Democrats and carried by Obama, but since then they have been governed by Republicans determined to impose highly conservative policies on previously Democratic states carried by Obama.

Who controls the country’s statehouses can matter a lot in presidential elections. For one thing, that’s where the rules and conditions for voting are set. In 2012 we saw the Republican governor of Florida and the attorney general of Ohio cut the number of polling places and the number of days and hours they were open in an obvious effort to limit the votes of blacks and other minorities, as well as poor seniors.

Though great numbers of voters rose up and insisted on casting their ballots, it’s still the case that large numbers—estimated at a minimum at hundreds of thousands—were prevented from voting. And in a close election a governor can be of significant aid to the national candidate: the state’s party machinery and the governor’s political network can be called on to help out. The ultimate example of how helpful a governor can be was provided by Jeb Bush in Florida in 2000.

As early as November of this year, two states, Virginia and New Jersey, will hold their contests for governor and senator. Usually of interest only to political obsessives, both states’ elections will be more widely watched for their implications for the 2016 presidential race, ridiculously early as it may be for that. In New Jersey, Governor Chris Christie, a relatively moderate Republican, is generally expected to be reelected easily but if he runs for president the main questions are whether his pugnacious style will be popular outside the state and how he will deal with the party base.

Virginia is more significant for national politics because it’s a swing state in federal elections—it was crucial to Obama’s reelection victory. The Virginia race for governor this November is an embarrassment. The Republican candidate, Ken Cuccinelli, who is even further to the right than Bob McDonnell, the current governor (who cannot run again), most famously wants to make consensual sodomy illegal in Virginia. That the proposal has been met with derision—and also some fright—and is clearly unconstitutional does not deter him.

Cuccinelli’s campaign is also suffering from the recent squalid revelations about McDonnell, who had already won national attention for backing transvaginal ultrasounds of women seeking abortions. McDonnell and his wife accepted considerable financial favors from a wealthy businessman whose products he then promoted—among other gifts, he picked up the cost of their daughter’s wedding and treated Mrs. McDonnell to a shopping spree at Bergdorf’s. Now Cuccinelli has been found taking favors from the same businessman, if on a more modest scale.

The Democratic nominee, Terry McAuliffe, the backslapping politician and businessman and close pal of the Clintons, has a problem of his own: one of his companies is under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission. To assure that this got a lot of publicity and to try to counter Cuccinelli’s problems, the right-wing activist David Bossie, founder of Citizens United, which brought the famous case of that name to the Supreme Court, has made a film (Fast Terry) charging McCauliffe with sleazy business practices. For good measure the Republican candidate for lieutenant governor, who is black, has called the Obamas communists who “don’t understand our country, I don’t think they even like it.”

Critical to the 2013–2014 midterm elections will be attempts to destroy the new health care law—the one issue the Republicans have found most effective for rallying their forces; that and “spending,” even as the deficit steadily declines, are the only two issues on which they have taken a real position. The obsessive attempt by conservative Republicans to prevent “Obamacare” from being implemented may be without precedent but it isn’t without purpose. By playing on people’s fears—proposed changes in health care arouse anxiety as no other domestic issue does—they are seeking to advance their own political cause. Even after it failed, “Hillarycare” was a major factor in the 1994 Republican sweep.

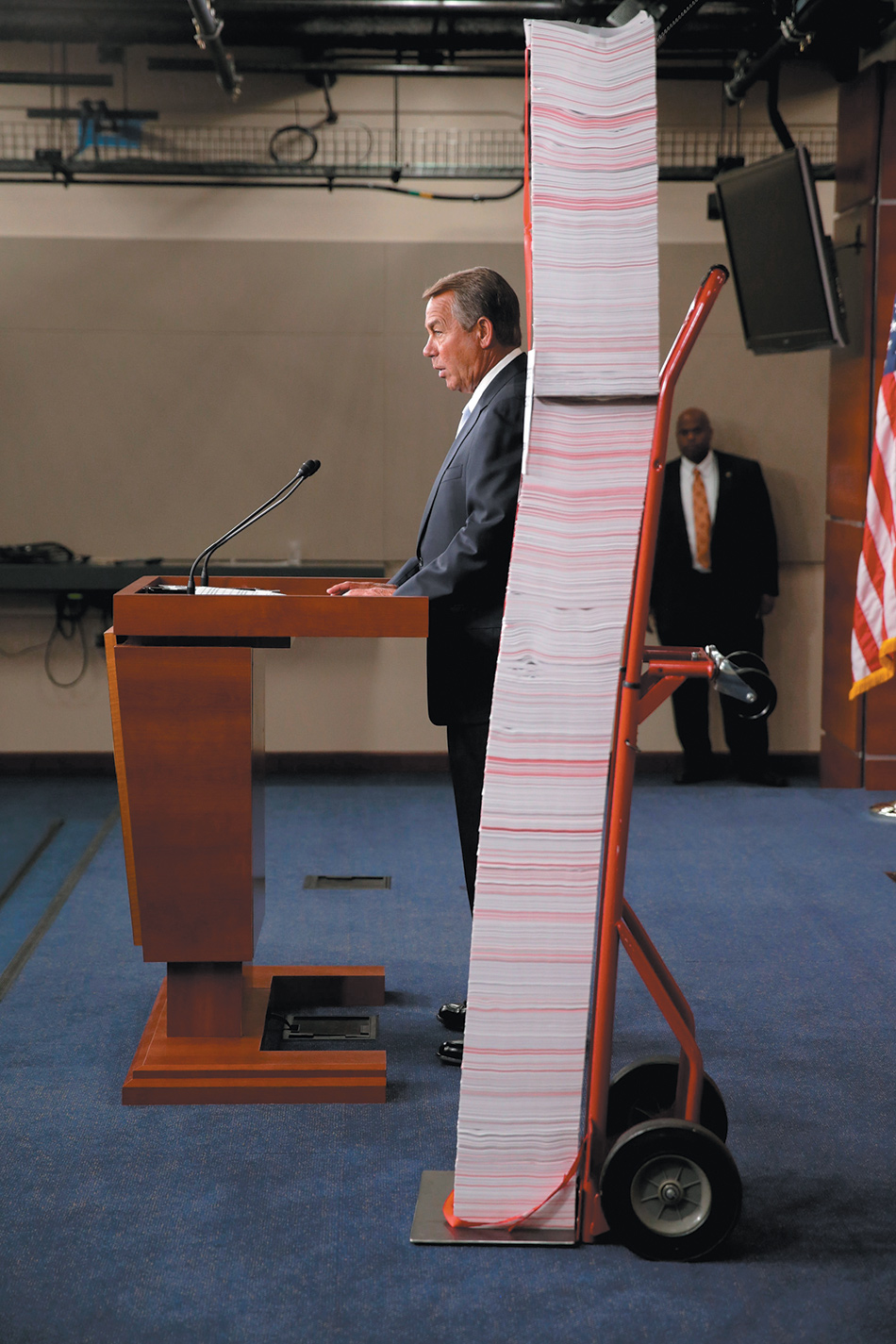

What began in 2009 as a movement to block passage of the health care program championed by Obama was transformed in 2010 into a furious reaction to its becoming law that was used as the organizing force in seeking Republican gains in those midterm elections. Since it worked then, why not have another go at it? The seemingly futile effort to repeal the law isn’t as silly as it seems. The forty roll-call votes by House Republicans to repeal it aren’t useless, even if there isn’t a chance that the Senate will agree. The Republican base strongly approves of these votes. The base has been mobilized around opposition to the health care law as a force for the midterms (and beyond) by the principal organizers and funders of the Tea Party in Washington as well as by the Heritage Foundation, the supposed think tank now headed by former South Carolina senator Jim DeMint. While in the Senate DeMint promoted Tea Party candidates for senator, several of them fools who flamed out. The votes not only help the Republicans raise money; they also provide protection for members trying to fend off attacks or challengers, enabling them to say, “I voted to kill Obamacare forty times.”

The Republicans are racing against the fact that some popular parts of the Affordable Care Act, such as the elimination of pre-conditions as a barrier for getting insurance and allowing parents to cover their children up to the age of twenty-six, have already gone into effect. If the complex health care program is seen as successful on the whole, Obama and the Democrats could get long-term credit for it, just as the Democrats did from Medicare. If the Republican fantasy were to come true and they somehow killed it off, Obama’s principal achievement will have been eliminated. Both parties understand that a health care program undergoing a lot of turmoil in 2014 spells trouble for the Democrats.

Egged on by a campaign run by FreedomWorks, the Tea Party stronghold in Washington, D.C., more than half (or twenty-seven) states have rejected the expansion of Medicaid for the ailing and elderly poor; and a majority of the states have also refused to set up the exchanges through which people can shop for medical insurance at presumably competitive prices. (This is partly a grandstanding gesture because the federal government will set up the exchanges in those states instead.)

FreedomWorks has urged people to burn their nonexistent “health care cards,” and it and other conservative groups are urging young people not to sign up for the new health insurance, and pay a penalty instead. The success of the plan depends on a certain number of healthy young people buying insurance on the exchanges in order to keep prices down for everyone else.

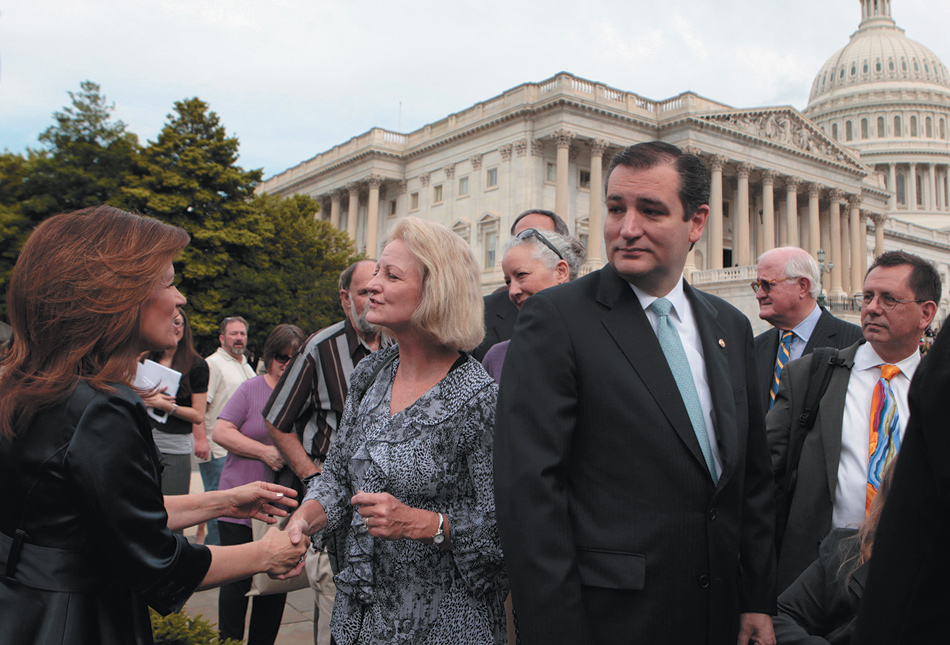

But in their zeal to eliminate a law that’s been passed and is on the books, congressional Republicans may have built their own trap. Whatever they do in the name of getting rid of the program or cutting it back is attacked by the most militant Republicans as insufficient; there’s always a more drastic proposal, and a demand from the base that they support it. A recent idea—backed by Senators Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and Mike Lee—was that the government be shut down unless “Obamacare” is defunded. But some senior Republicans with memories of the calamity to their party caused by the Newt Gingrich–led shutdown in 1995–1996, as well as governors with national ambitions, were outspoken in calling this a stupid idea. Cruz, at the center of the effort, showed in his first weeks in the Senate that he’s not above McCarthyite tactics (as in the Hagel hearings); and he freely breaks the rules and understandings by which the Senate functions at all. Most uncommonly, he is actually hated and feared by most of his colleagues (including Republicans)—such strong feelings about a fellow senator are rare. The Harvard Law graduate and able advocate before the Supreme Court dismissed his senior Republicans’ concerns and in his mellifluous tone said that they were misreading history, and he carried on a crusade for a shutdown, which few of his colleagues liked.

But the ruffian Cruz overstepped and made a big mistake. As he traveled around with DeMint, he aroused great cheers from crowds at town meetings in August—but his colleagues held firm; no additional sponsors of the shutdown proposal came forth. Beyond that, Cruz and DeMint threatened Senate Republicans—true conservatives such as Tom Coburn and Lindsay Graham—who refused to back the shutdown with primary challenges. (Cruz is far more intelligent than DeMint but in defying the leaders of his party he is following his own agenda.) The base doesn’t mind if he’s unpopular in Washington, though.

Struggling once more to convince his far-right caucus members to take a less self-damaging route than the shutdown, the beleaguered Speaker John Boehner suggested that instead of shutting down the government unless Obamacare is defunded or postponed—anything to keep it from going into effect by the 2014 elections—they delay passing an increase in the debt ceiling. Holding up the debt ceiling in 2011 brought all kinds of obloquy down on the heads of the House Republicans and also stupidly hurt the credit standing of the US. Boehner has been leaping from ice floe to ice floe, each one more dangerous. So far his strategy of postponing calamity has worked—but what happens if he runs out of ice floes?

The agony of the current Republican Party is that most of the far right isn’t concerned about the possible effects of their tactics on the national party—on its ability to win not just the next presidential election but also other offices down the line. The Tea Party members of Congress are responding to their districts. But the mainstream Republicans are panicked that they have lost four out of the last six presidential elections, and they have yet to figure out how to placate their base in the nomination process and still win the general election. But the far right has its own version of reality. Some even plan to run for president on it.

As a result of the centrifugal forces that have taken over our politics, we have ended up with warring political blocs, not with the federal system envisioned by the Founders. Instead of cooperative interaction among the states and the federal government, we have a series of struggles between them. Federal laws are blocked or degraded in many of the states, and state obligations are unmet. After the country reelected a Democratic president in 2012, the Republicans continued to refuse to recognize his legitimacy and they opposed virtually his every policy proposal. (Whether immigration will break this pattern is up in the air.) Meanwhile the most sweeping changes in domestic policy are taking place in states dominated by Republicans. As it turns out, 56 percent of the population, and 60 percent of poor children, live in these states.

The new turbulence between the federal government and the states and between the president and Congress has been exacerbated by midterm elections. The turbulence has been spreading across our governing institutions—putting the very workability of the American political system in jeopardy. With the House in the grip of the very far right, the wreckers have made it almost impossible for Boehner to lead—and Obama to govern.

The madness has been seeping into the usually more staid Senate, to the point where freshman radicals—Rand Paul, Cruz, and Rubio, with the Tea Party at their backs and a presidential gleam in their eyes—can break with longstanding precedent and courtesies and presume to define the national agenda. Minority leader Mitch McConnell is being challenged for renomination by a Tea Party member, which has limited his leadership capacities and his judgment. The turbulence has spread into the Supreme Court. Our federal organism is a delicate instrument, one that can work reasonably well only if its caretakers proceed on the basis of understandings and restraint.

The seeds of this situation were planted in the 1994 midterm election that swept the former back bencher Newt Gingrich into the Speakership of the House. Gingrich rashly maneuvered himself into a government shutdown that ended in disaster for the Republicans. (Bill Clinton outmaneuvered Gingrich, and the public didn’t at all appreciate the shutdown of federal services.) There is no evidence that Gingrich had thought through the consequences. He thus spawned the consequence-free politics that is now bedeviling our system of government. In 2009, for the first time, defeat of the incoming president in the next election became the opposition party’s explicit governing principle. If that meant blocking measures to improve the economy, or preventing the filling of important federal offices to keep the government running, so be it. Wrecking became the order of the day. Confrontation became the goal in itself. Now the rightward trend in Republican politics is feeding on itself, becoming even more extreme until the preposterous becomes conceivable.

Can this chokehold on our politics be broken? Several states are considering the possible removal of the power to control redistricting from the politicians who stand to benefit from their own decisions. Arizona and California have adopted independent commissions to redraw districts.

Theoretically, Congress could pass legislation requiring the states to reform their redistricting practices for federal elections; but that would require a sufficiently powerful movement—of which there is no sign—to put pressure on members of Congress to act against their own perceived interest.

The citizens of a state have it within their power to press for such changes in the nature of their state governments and the consequent effects on their immediate lives as well as the functioning of the nation’s political system. By rousing themselves to vote, they could have a stronger voice in filling state offices that may not seem so exciting but are highly consequential. Is it possible that the off-year elections could be taken almost as seriously as the presidential ones? The radicalism of the right has become so extreme that it may have unintentionally provided an impetus in that direction.

In the end only the members of the electorate can restore the institutions and procedures that make our democratic system work, starting with the next chance they get.

—August 27, 2013

This Issue

September 26, 2013

The American Jewish Cocoon

They’re Taking Over!