Bill de Blasio’s victory on September 10 in New York City’s Democratic primary for mayor is a reminder that through some inexplicable emanation, certain New York mayors have caught perfectly the gestalt of the city. Who can forget Abe Beame, the five-foot-two-inch Polish Jewish accountant, subsumed in the fog of New York’s impending bankruptcy and crumbling streets? During Beame’s administration in the mid-1970s, money was so tight that a subway maintenance worker told me he would rip up track from one part of a tunnel to repair damage somewhere else down the line.

David Dinkins, whose one term ended in 1993, was New York’s last Democratic mayor. He was also New York’s only black mayor, elected partly as a corrective to Ed Koch, who many felt had needlessly inflamed racial tensions in the city. Dinkins spent his early childhood in Trenton, New Jersey, where his father ran “a one-chair barbershop on the ground floor of the row house in which we lived. I shined the shoes of the men who came for a cut and a shave,” he writes in his autobiography.1 When he was six he moved with his mother to Harlem. “We never stayed in one place very long; we moved when the rent was due. My mother and grandmother both worked as domestics, cooking and cleaning for white folks for a dollar a day.” He describes himself as “an obedient child,” and it was that diligent, survivalist hardship of the Depression years that formed him. As mayor, he appointed Ray Kelly to be police commissioner and was widely praised as a conciliator after the Rodney King verdict in 1992: while riots erupted in Los Angeles, Atlanta, Philadelphia, and elsewhere across the country, New York City remained peaceful.

A year earlier, however, Dinkins had been politically undone by a neighborhood civil war between members of the Lubavitch Hasidic sect and West Indian blacks in Crown Heights. Stewing resentments between the two groups came to a boil after a young boy was killed by a car in the Lubavitch rabbi’s motorcade that had swerved out of control. A few hours later, a group of black men killed a rabbinical student on the street. In his handling of the crisis, the mayor weakly fell under the spell of Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, and, worst of all, radical neighborhood activists, or so the news stories suggested. An exaggerated sense of encroaching lawlessness and racial fear took hold of a large swath of New Yorkers, and in 1993 they elected Rudolph Giuliani, an outer-borough, parochial school–educated, Italian-American Catholic, a product of one of the most racially segregated and conservative communities in New York.

Giuliani attended Bishop Coughlin High School in Brooklyn, “the Exeter or Andover for working-class Catholic kids from Brooklyn, Queens and Long Island,” according to his unauthorized biographer, Wayne Barrett. Of the 744 students in his class, three were black and four were Hispanic. Giuliani’s father, Harold, spent sixteen months in prison for sticking a loaded gun in a milkman’s stomach and robbing him of the $128 he had collected on his rounds.

Later, Harold worked as a bartender and debt collector for his brother-in-law, who ran a loan-sharking and bookmaking operation out of a bar in East Flatbush. Harold was the “muscle.” Because of his violent outbursts, his wife, Giuliani’s mother, referred to him as “the savage.” There seemed to be a complicated personal feeling of necessity at work when, as the chief federal prosecutor of New York, Rudy Giuliani went after mobsters, and then, as mayor, deployed elite, quick-to-draw, plainclothes police squads to prowl poor neighborhoods in the manner of hired gangs.

Michael Bloomberg, the reserved son of a real estate agent, from the rather nondescript suburb of Medford, Massachusetts, seemed oddly foreign to New York when he succeeded Giuliani in 2002. Perhaps it was the padding of his enormous wealth or his clipped manner or his imported, antipolitical sense of efficiency that gave him the aura of a blandly unreachable commander. In matters of policy he was certainly bold: his various plans to combat the rising waters of global warming after Hurricane Sandy; the 2003 smoking ban and other public health initiatives, many of them involving the care of indigent children; the creation of new parks throughout the five boroughs; the improvement in transport; and his earnest (and not always successful) attempts to reconfigure the city’s public school system, to name a few. But the imperiously guarded air that engulfed him made his accomplishments seem like the impersonal edicts of a distant man.

Bloomberg’s famous “bullpen” renovation at City Hall turned the mayor’s office, in the words of Bill Thompson, his Democratic opponent in 2009, into “a trading desk.” He presented himself as a data-based mayor, guided almost exclusively by the finality of statistical information. This was, after all, the basis of his fortune: stock and bond information terminals for hire. The cosmetic lift he presided over in certain parts of Manhattan—one thinks of Times Square and his support of the Hudson and East River parks—gave the city a relaxed, civically content feeling, but one that sometimes felt false, like a derelict donning a custom-made suit. He seemed in the thrall of Ray Kelly, as if Kelly’s soldierly police force reflected, one longtime Bloomberg watcher put it to me, “Bloomberg’s inner personality.” Kelly was cast as New York’s inviolable protector, and the mayor appeared to have no real sense of the suffering and humiliation that his data-driven stop-and-frisk policies caused.

Advertisement

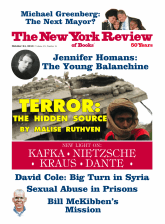

Bill de Blasio, in contrast, did seem to grasp the personal cost of humiliation by the police and was able to dramatize it through the image of his fifteen-year-old biracial son, Dante. Like Bloomberg, de Blasio grew up in a Boston suburb—Cambridge, in his case. But with his public school–educated children and his arrest, with handcuffs, on July 10 while protesting the State University of New York’s closing of Long Island College Hospital in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, he projects the image of a man habitually engaged in the nitty-gritty of New York life. (On September 12, the New York State Supreme Court stopped the hospital’s closing, ruling that it had not taken the community’s needs into account.) He represents an almost fairy-tale idea of how many New Yorkers wish to see their city: racially harmonious, enlightened, empathetic—a wish that finds assurance, perhaps, in de Blasio’s ever-so-vaguely patrician demeanor.

His towering height (he is six foot five) seems to have given way to a compensatingly soft delivery, as if he has conditioned himself not to intimidate or overwhelm. On the day before the primary, I watched him campaign in Washington Heights, craning down to listen to the complaints of a Dominican woman with a walker, while his eighteen-year-old daughter, Chiara, wearing a crown of paper flowers, stood by. The de Blasio family is clearly delighted with itself. The children appear, at least, to be immune to the surliness and discontents of adolescence. The campaign has turned them into celebrities, but one can foresee a moment when de Blasio’s insistence on his personal happiness could begin to beleaguer voters rather than excite them.

And yet, in a comical series of identity politics one-upmanship, de Blasio’s family helped him strip his Democratic primary rivals of their core constituencies. Christine Quinn offered the voters the chance to make her the first female—and lesbian—mayor. But it emerged that de Blasio’s wife, Chirlane McCray, a self-described “activist [and] writer,” had also been a lesbian; voters could, more exotically, make de Blasio the first white male mayor with a black and former lesbian wife.

The de Blasio family also trumped Bill Thompson’s putatively secure support among blacks, and especially among black women. Several women told me they appreciated de Blasio’s apparent devotion to his wife. (“We like it, it makes us feel loved,” a middle-aged black woman in Washington Heights told me. “Black men with white women, you know, are much more common than the other way around.”)

But the issue that most contributed to de Blasio’s victory was stop and frisk. He unequivocally denounced the practice at a time when Kelly’s approval rating topped 70 percent and Bloomberg’s popularity still rode high. (De Blasio himself at the time was polling at around 10 percent.) Thompson and Quinn, the front-runners, were wary of criticizing the practice. In a debate at NYU in April, Thompson said, “Kelly has done an excellent job. I haven’t said stop Stop and Frisk. It’s a useful tool.” Quinn, for her part, said, “Any of us would be lucky with Ray Kelly as commissioner.” She repeatedly referred to the practice as “stop, question, and frisk,” a linguistic softening of its impact that was at odds with reality. The “question” in the equation—a sense of politeness and consideration toward the targets—was precisely what was missing. Quinn’s inability to acknowledge this, coupled with “the taint of the transactional” that surrounded her (in the fine phrase of the New York Times reporter Ginia Bellafante), the sense that as city council president she had served Bloomberg’s purposes, cutting backroom deals with the mayor and blocking bills he opposed, did much to stall her campaign.

What hurt Quinn most, however, was her staccato recitation of small-bore issues, her exhaustive preparedness, her minute knowledge of the latest impact study—all attributes that would seem like a virtue in a candidate but that failed to speak to the broader unease many Democratic voters felt about the social and economic tilt of the city over the past twenty years. Making the case, during a debate last spring, for why she should be elected mayor, Quinn said she would stop firehouse closings, avoid teacher layoffs, and provide “good management of New York City’s finances.” After twelve years of Bloomberg, a master bureaucrat wasn’t what voters were looking for.

Advertisement

Only de Blasio strongly opposed stop and frisk from the outset of his campaign, endorsing the appointment of an independent inspector general “with subpoena power,” in his words, to oversee the NYPD. The other candidates supported an inspector general if he was appointed from within the department—all but guaranteeing that he would not challenge the police commissioner. (John Liu, the outspoken city comptroller, also supported an independent inspector general, but a campaign finance scandal doomed his candidacy from the start.)

On August 12, less than a month before the primary, US District Judge Shira Scheindlin ruled that stop and frisk violated the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments for its illegal use of search and seizure and its disregard of the Constitution’s equal protection clause. In response, both Thompson and Quinn shifted gears on the issue, but it was too late. In her searing, elegantly written ruling, Scheindlin called stop and frisk a tactic of “indirect racial profiling,” and ordered the appointment of a federal monitor to institute broad reforms to the practice. De Blasio’s long-held position was vindicated by a federal court.

The ruling appeared definitively to change the race: the seemingly impermeable armor of public support that had protected Kelly and Bloomberg for years began to crack. Bloomberg angrily shot back that Judge Scheindlin didn’t “understand how policing works,” adding that New Yorkers wouldn’t be seeing “any changes in tactics overnight.” (The city is appealing the ruling.) In the days just before the primary, an aggrieved defensiveness seemed to take hold of both men. Bloomberg unintentionally boosted de Blasio by calling his use of his family in the campaign “racist” and accusing him of advocating “class warfare.” (Through a spokesman he retracted the word “racist.”)

On the day before the primary, Kelly sounded unusually offended as he complained, in a speech at the Council on Foreign Relations, that none of the candidates had come to him to be schooled in the ways of the NYPD’s antiterror program. The candidates, including the Republican nominee, Joe Lhota—a former deputy mayor under Giuliani and former chief of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority under Bloomberg—dismissed the complaint, saying that such a briefing would be premature.

After the primary was over, during an interview with the affably fair-minded reporter Errol Louis of NY1, Kelly bristled at Louis’s mild questions about the NYPD’s Intelligence Division’s possible encroachment on the civil liberties of New York’s Muslims. Kelly repeatedly suggested that his efforts to protect the city had not been appreciated or understood. It should be noted that, apparently out of fear of being branded “soft on terror,” no candidate during the primary campaign raised the issue of the NYPD’s extensive program of spying on law-abiding Muslims.2 It seems certain, however, that Kelly will be replaced if de Blasio is elected.

The dearth of “affordable housing,” a buzz phrase of most of the candidates during the campaign, is the issue that goes most directly to the core of New York’s growing economic divide. “Affordable” is commonly defined as housing that costs no more than 30 percent of the city’s median household income (currently estimated at $50,895), or around $1,275 per month. In 2011, only 44 percent of rental apartments in the city were considered affordable by this measure, and 55 percent of renters were paying over 30 percent of their income for housing. (Roughly two thirds of New Yorkers rent their homes.) These figures do not take into account roommates, subletters of single rooms, and families that double up to share costs. According to new census data released on September 19, the poverty rate in 2012 in New York City rose to 21.2 percent from 20.9 percent the year before, and 20.1 percent in 2010. Some 1.7 million New Yorkers fall below the federal poverty threshold.

If de Blasio is elected mayor, what can reasonably be expected to change? As a councilman his policy was much the same as Bloomberg’s: to work with real estate developers to ease the way for large-scale projects, while attaching to these projects as many units of below-market housing as the developers would accept. De Blasio was a staunch supporter of the enormous Atlantic Yards development in downtown Brooklyn. He also helped to push through the City Council two development-friendly rezoning laws in Brooklyn’s Gowanus neighborhood that included no affordable housing.

The fact is that property taxes—$18.6 billion in 2013—make up nearly half of New York City’s tax revenue, more than double the revenue from personal income tax. The city pays for basic services largely on the assumption of an ongoing real estate boom.

More often than not, the assumption is correct. Unlike in most cities, increasing supply doesn’t drive down housing costs in New York, where demand over the past twenty years has been inexhaustible. The problem seems insoluble. New York’s population—8.4 million—is the highest it has been in sixty years. The city has lost more than 230,000 rent-regulated units over the past three decades. When a rent-stabilized apartment reaches $2,500 per month, it ceases to be subject to regulation if it becomes vacant or if the tenants’ annual household income for two consecutive years exceeds a set amount (currently $200,000). The landlord is then free to rent it for as much as the market will bear. An apartment that rents today for $2,000 could, with the annual increase allowed by the city (now 4 percent for a one-year lease) become deregulated in about five years, at which point the rent might double or go even higher.

For all its woes, the New York City Housing Authority currently has 167,353 families on its waiting list. The city’s homeless shelters house 50,000 people, the highest number in its history. By the end of his third term, Bloomberg will have built or preserved 165,000 affordable and low-income units—an impressive number, but one that has been unable to keep pace with the market. De Blasio has promised to go further and build or preserve 24,000 affordable units per year. He claims he can reach that number by easing air-rights statutes, requiring developers in rezoned districts to commit to building more affordable units (though his record in doing so in his Brooklyn district has been mixed), and investing the city’s $1 billion worth of pension funds in affordable housing projects. These seem like reasonable proposals. But their ability to alleviate substantially New York’s persistent housing crisis is questionable.

A Marist poll released on September 17 gave de Blasio a 43 percent advantage over Lhota among likely voters in the general election to take place on November 5. If his popularity holds, he will be the next mayor of New York. Socially, he represents a picture of the city radically different from Bloomberg’s. Whatever further changes he might bring to the texture of New York life, and whatever the outcome of the court’s decision about the police, it seems safe to predict that in a de Blasio administration the average black or Hispanic male will be able to lawfully walk the streets with less fear of being harassed.

-

1

A Mayor’s Life: Governing New York’s Gorgeous Mosaic (PublicAffairs, 2013). ↩

-

2

See my articles on the NYPD’s Intelligence Division in The New York Review, October 11 and October 25, 2012. ↩