The subtitle of the splendid exhibition of works by Balthus at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is really a misnomer. For there is no evidence that Balthus painted adolescent girls, let alone cats, as provocations. Which is not to say that he never set out to shock. His painting The Guitar Lesson shows a music teacher, modeled after Balthus’s own mother, maliciously pulling the hair and pawing the crotch of a half-naked girl in white knee socks sprawled helplessly across her lap. Robert Hughes called this picture of molestation “one of the few masterpieces among erotic paintings by Western artists in the last fifty years.”

The Guitar Lesson, not on view in the Met show, was once stored at the Museum of Modern Art, then sold to the filmmaker Mike Nichols, and now belongs to the Niarchos family—the old shipping tycoon Stavros Niarchos had it in his palatial bedroom.

When The Guitar Lesson was shown for the first time in 1934, at a gallery in Paris, it caused a stir. But the shock experienced by viewers then may have had less to do with sadomasochism than with Balthus’s mocking intent. As Sabine Rewald, the great Balthus scholar and curator of the current show, observed in the catalog of her earlier Balthus exhibition at the Met in 1984, The Guitar Lesson parodies a common theme in European art of music lessons turning into scenes of seduction. But Balthus did something more shocking: the painting echoed in its composition a famous French picture of the corpse of Christ held by the Virgin: Pietà de Villeneuve-lès-Avignon (circa 1455). The parody was blasphemous.

Blasphemy is less likely to upset people now than an erotic depiction of an adolescent. For we have sex on our minds more than religion. Even Max Ernst’s far more sacrilegious image of the Virgin spanking her son (The Blessed Virgin Chastising the Infant Jesus, 1926) has lost much of its power to upset.

Unlike The Guitar Lesson, however, none of the pictures of young girls in the latest show at the Met is overtly sadistic. So why must they be called provocations? The answer seems to be clear: it anticipates sensitivities that were far less common when the pictures were made. The sexuality of children, and especially their sexual allure for adults, is today’s most fiercely guarded taboo.

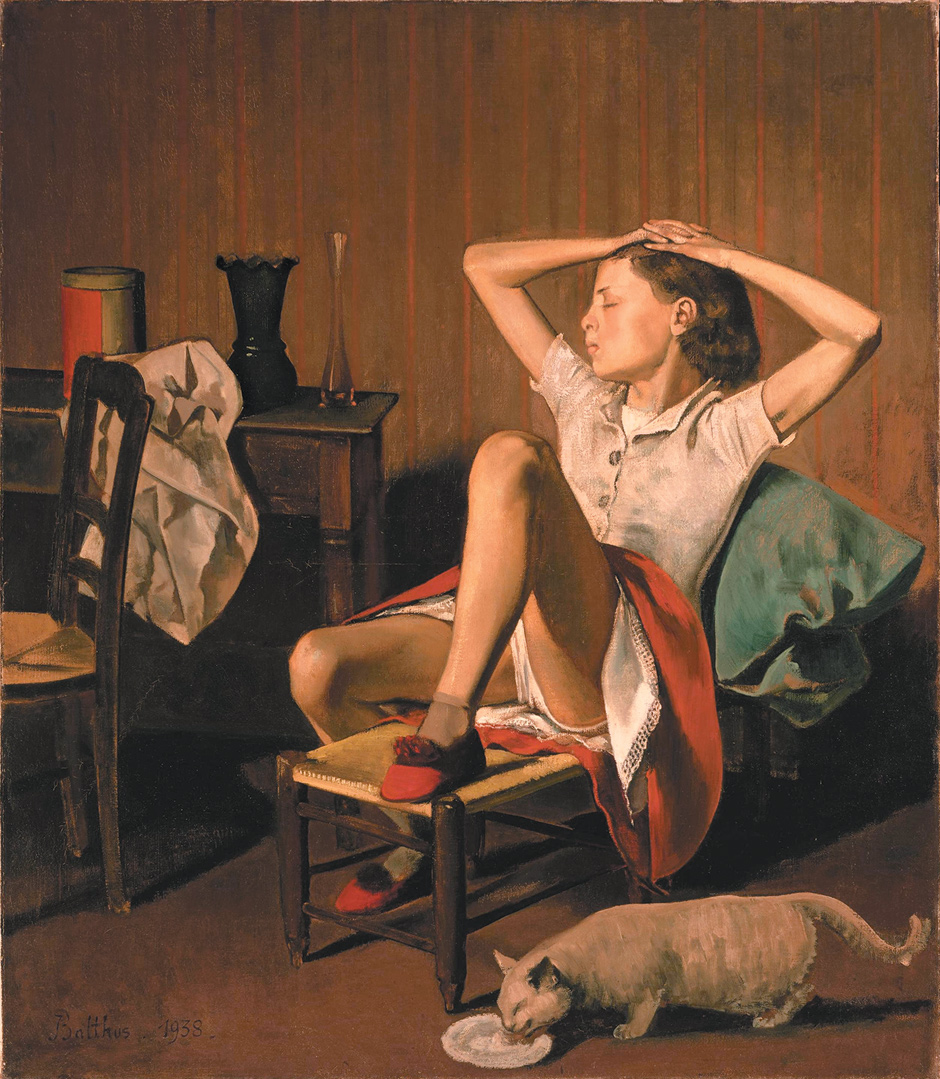

To be sure, the marvelous paintings by Balthus of the twelve-year-old Thérèse, dreamily gazing at the viewer with her white panties showing (Thérèse with Cat, 1937), or the painting reproduced in the catalog of the nude Laurence Bataille (daughter of Georges Bataille) stretched back, cat-like, in a chair, while a sinister-looking person draws the curtains to throw light on her naked form (The Room, 1952–1954), are unsettling, but not because of anything pornographic. Far more blatantly erotic pictures were done by Egon Schiele or Otto Dix, or indeed Picasso. What is disturbing about Balthus’s pictures of girls is not just the age of his models, but the atmosphere, which is creepy, full of dread and latent violence, and yet extraordinarily beautiful. Girls are trapped in angular, often tortuous poses in tight gloomy spaces. There is something in Balthus’s art of those claustrophobic Victorian novels about children locked up in dark attics.

Childhood was a major inspiration for Balthus. Like James Barrie, creator of Peter Pan, or Lewis Carroll, whom Balthus much admired, he wanted to lurk forever, in his art if not in life, in the dreamscape of early adolescence. Artists and writers attracted to childhood are often drawn to innocence—innocence as a state of grace, threatened by the adult world. This was certainly true of Barrie. The exact nature of Lewis Carroll’s feelings for the model of his stories, a child named Alice Liddell, will always be somewhat opaque, but his art, though not without dark undertones, is not knowingly erotic. The same cannot be claimed for Balthus’s paintings.

Like Carroll, Balthus enjoyed the company of young people, as well as of cats. In fact, cats and young girls have much in common in his paintings. They are imbued with the same air of mystery, of dreaminess, of a sensuousness that can be self-conscious and innocent at the same time. Adolescent girls sense the effect they have on adults, without quite understanding its implications, although this was perhaps more true at a time when hardcore pornography was not yet a click away. Like cats, young people often seem to be drifting off in a world of their own. It was this state of solipsistic languor that Balthus caught in his best paintings.

Some of his girls are entranced, like Narcissus, by the mirror image of themselves. In the exquisite painting The Golden Days (1944–1946), for example, we see the fourteen-year-old Odile Bugnon gazing into a mirror, her bared legs lolling from a Victorian chaise, while an older man is stoking the fire in the background. There is no clear story here (Balthus hated narrative paintings). But a great deal is suggested. This is true of his other masterpieces of the 1930s as well. Consider, for example, The Mountain in the Met’s own collection. What are those people doing on an Alpine mountaintop? One girl stretches herself like a cat, another is in deep sleep, and the artist himself is pensively leaning on his stick.

Advertisement

When Balthus later denied that his paintings of young girls had any erotic intent, he was being disingenuous. There are plenty of hints to the contrary. The Golden Days is one example. The cat licking from a bowl of milk at the foot of a chair where young Thérèse is dreaming, her skirts hitched up to reveal her white panties (Thérèse Dreaming, 1938), is another. And there are more.

But to denounce these pictures as the work of a pedophile would be as absurd as to revile Caravaggio’s paintings as the wicked effusions of a pederast. Balthus painted from his imagination, after sketching his models. No child was ever abused. And besides, the particular beauty of children on the cusp of becoming adults is hardly new. Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice is an expression of what Germans used to call Knabenliebe (love of young boys). Even if one disapproves of adults having sex with adolescent boys or girls, Mann’s Tazio, like the subjects of Balthus’s pictures, is an aesthetic ideal, the celebration of which is an ancient artistic tradition.

It would be a philistine mistake, in any case, to judge Balthus’s art purely on its subject matter. At least as interesting are the formal qualities of his paintings. Balthus and the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe had little in common, except for one thing: they imposed beautifully executed classical forms on their erotic fetishes. Mapplethorpe photographed black male genitals with the same care and sense of stylistic precision that he lavished on pictures of orchids. The British critic Cyril Connolly, an early admirer of Balthus, described this approach as “a deliberate opposition” between the subject and its treatment in paint.

Like Mapplethorpe, Balthus was a formalist, with a deep and learned interest in art history. There are many allusions in his pictures to earlier masters, from Piero della Francesca to Géricault. One of the wonders of his best paintings is his technical skill, which is all the more astonishing in that he was self-taught. Some of the details in the paintings—glasses of wine, a silver knife stuck into a loaf of bread, bottles of various kinds on shelves—show the virtuosity of a master of still lifes.

Balthus’s natural talent was already apparent in the series of ink drawing he made at the age of eleven of the adventures of Mitsou, a stray cat. His mother’s lover at the time, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, was so impressed that he organized the publication of these pictures, and provided the preface himself. This rare book, as well as the original drawings, is on display in the show at the Met.

Unfortunately, Balthus’s formalistic side would later become pure formalism. The pictures in the last room of the exhibition, painted in the late 1950s, some of them mimicking Italian frescoes or echoing the Romanticism of nineteenth-century German artists such as Caspar David Friedrich, are aesthetically pleasing, well executed, decorative, but entirely lacking in the dark mystery of the earlier works. In Sabine Rewald’s account, this had something to do with the artist’s circumstances. His most interesting paintings date to his time in Paris, where he was part of the bohemian circles around Antonin Artaud and Albert Camus. He was an artist among other artists, designing sets for the theater, making portraits on commission. The febrile atmosphere of Paris, with its teeming streets, its cafés full of talk, and its promise of erotic possibilities, sparked his imagination.

But then, during the war, he moved to Switzerland, and in 1953 to a château in central France, where he could indulge his fantasies of himself as a grand seigneur, inventing fake ancestries (Lord Byron) and bogus titles: Count Klossowski de Rola. Instead of being the son of Erich Klossowski, a Polish art historian of good family, and a Russian Jewish artist named Elisabeth “Baladine” Spiro, he claimed to be the scion of the highest Russian and Polish nobility. Later, when he married Ideta Setsuko, a Japanese, the Rola coat of arms would adorn the kimono he wore in his grand chalet in Switzerland.

None of this would be of great importance—artists are entitled to making things up—if his increasing delusions of grandeur, matched with considerable wealth, had not gone hand in hand with a deterioration of his art. From being a disturbing original, Balthus became a mannerist, pleasing to his collectors, many of them living in the US, a nation he professed to despise.

Advertisement

The exhibition at the Met, however, those last few paintings apart, shows Balthus at his very best. It would be a shame if current attitudes toward sexuality, however justified they may be in real life, were to obscure the art of one of the last masters in the classical European tradition.

This Issue

November 7, 2013

Love in the Gardens

Gambling with Civilization

On Reading Proust