Ronald Dworkin contributed over one hundred articles, reviews, and comments to these pages starting in March 1968. The following was originally given as a talk at the Palazzo del Quirinale in Rome in November 2012, when he received the Balzan Prize for his “fundamental contributions to Jurisprudence, characterized by outstanding originality and clarity of thought in a continuing and fruitful interaction with ethical and political theories and with legal practices.” It is presented here with small changes. Ronald Dworkin died on February 14 of this year.

Law is at the cutting edge of many different disciplines and I am going to try to illustrate this point by talking about my own career, not because I believe that everything I think is right, but because my career has illustrated a marked trajectory from the very concrete to the very abstract.

My last book, Justice for Hedgehogs (2011), offers a panorama of the work I have done over half a century: not just a survey but an integration, trying to explain how it all fits together. I began my professional life as a young lawyer in a grand Wall Street law firm. My work could not have been more detailed and less abstract then. I wrote elaborate bond indentures and studied the balance sheets of giant corporations, helping them to satisfy the laws that allowed them to raise more money and grow greater still.

Since then, in an academic career at several institutions, my interests have grown steadily more abstract. But in each case the intellectual pressure I felt developed from the bottom up, not the top down. I took up steadily more abstract philosophical issues only because the more practical and political issues that first drew my attention seemed to me to demand a more philosophical approach to reach a satisfactory resolution. I will try to illustrate that process of philosophical ascent here.

When I left Wall Street to join a law school faculty, I took up a branch of law—constitutional law—that is in the United States of immediate and capital political importance. Our Constitution sets out individual rights that it declares immune from government violation. That means that even a democratically elected parliament, representing a majority opinion, has no legal power to abridge the rights the Constitution declares. But it declares these individual rights in very abstract language, often in the language of abstract moral principle. It declares, for example, that government shall not deny the freedom of speech, or impose cruel punishments, or deprive anyone of life, liberty, or property without due process or law, or of the equal protection of the law.

The Supreme Court has the final word on how these abstract clauses will be interpreted, and a great many of the most consequential political decisions taken in the United States over its history were decisions of that Court. The terrible Civil War was in part provoked by the Supreme Court’s decision that slaves were property and had no constitutional rights; racial justice was severely damaged, after that war, by the Court’s decision that racially segregated public schools and other facilities did not deny equal protection of the law; a good deal of Franklin Roosevelt’s progressive economic legislation was declared unconstitutional because it invaded property rights and so denied due process. These were the bad decisions that everyone now regrets. There have been very good decisions, too: in 1954 the Court, reversing its earlier bad decision, declared that segregated schools were inherently unequal, and therefore did deny equal protection of the law.

It is therefore a crucial question how courts should interpret the abstract constitutional language: What makes a particular reading of that language correct or incorrect? But the Constitution is law—it declares itself to be the most fundamental law—and so the question how it should be interpreted is really only one form of the ancient jurisprudential question: What is law? How should judges decide what the law of some nation really is on some particular subject? Over centuries philosophers have disagreed. In recent times one theory of law—it is called legal positivism—has been particularly influential. This declares that what the law is on some subject in no way depends on what the law ought to be. What the law is depends, according to positivism, not on morality, but only on history: on what people given the appropriate authority have declared it to be. We discover what the law on any subject is, according to positivism, by identifying those in authority and finding out what they have said.

In most cases this is a relatively easy matter. There are books that set out civil codes and record the other decisions of parliaments and the past rulings of judges. Lawyers know where these books are kept, and how to read them. But what if lawmakers speak in abstract language and what they say can be read in different ways? The United States Constitution forbids “cruel” punishments. Does that rule out capital punishment—the death penalty?

Two answers are open to legal positivists. They can say that since the “framers” who made the Constitution didn’t say one way or the other, there is no law on the subject, and the Supreme Court is therefore free to make up its own mind. But that sounds profoundly undemocratic. Or a positivist can say that the answer depends on what the framers intended, or expected, or would have declared if they had thought of the question. In this case that strategy decides the issue. Since capital punishment was widely used in the United States in the early eighteenth century, when the framers published their clause, they could not have intended or expected to declare it unconstitutional. Therefore it is not, even now, unconstitutional.

Advertisement

So it is of great practical consequence whether legal positivism is a sound philosophy of law; that is important not only in the United States but now in all the many other countries, including Italy, that subscribe to abstract constitutional rights. One can’t properly understand or participate in constitutional law without taking a stand on that subject. So I did. From the 1960s until the present, I have argued in a variety of books and articles that it is very much unsound. It provides only an incompetent description of the actual practice of law. Lawyers and judges typically make claims about what the law actually is that cannot be thought to be grounded just in what authoritative bodies have previously declared.

Even more fundamentally, legal positivism is based on severe misunderstandings in the philosophy of language. It assumes that we share the concept of law the way we share the concept of a triangle, that is, that we all agree on the tests to use to decide whether a legal claim is true or false. But we do not. For us, the concept of law—like other political concepts such as the concept of justice—is an interpretive concept: a theory of law is a normative claim about the tests that we should use to judge claims of law. A theory of law is a special kind of political theory, and so what law is cannot be separated completely from what it should be.

Once we reject positivism, however, we need another, different theory of law. In a series of articles and then in Law’s Empire, in 1986, I offered a theory. A claim of law should be understood as a claim about the best interpretation of past and contemporary legal and political practices in the nation in question. We need a theory of what interpretation is—about what counts as a successful interpretation—in order to fill out this interpretive theory. I proposed what I came to call a “value” theory of interpretation. An interpretation must fit the data—it must fit the practices and history it claims to interpret—but it must also provide a justification for those practices. It must, as I sometimes put it, show the practice in its best light. The first requirement—of fit—is not enough on its own, because more than one interpretation of a complex set of legal data may fit well enough to count. The second requirement—of justification—is therefore crucial. It shows why positivism must fail as a general theory of law. We cannot identify law without assuming some justification, however weak, in political morality.

This account of what interpretation is, and of what makes one interpretation succeed and another fail, cannot hold only for legal reasoning, however. It must hold for interpretation in general, and so I was required to explore other domains of interpretation. In one important chapter of Justice for Hedgehogs, I concentrated on artistic and literary interpretation. I tried to show how the “value” theory of interpretation illuminates the agreements and conflicts among critics in all these domains.

The interpretive theory of law raises deeper questions about moral philosophy. It supposes that one claim about the law—that capital punishment is unconstitutional, for instance—can be true and its opposite false, even though its truth depends on a moral theory about the best interpretation of the Constitution as a whole. But for many decades now most influential moral philosophers have denied this. They insist that claims about morality—that capital punishment is morally wrong, for example—are not really judgments and so cannot be either true or false. Since judgments about moral rights and duties cannot be empirically tested, these philosophers say, it makes no sense to think that they are either true or false. We must either concede that such judgments are, strictly speaking, nonsense, or we must suppose that they are not really judgments at all, but only expressions of emotion or recommendations for conduct.

Now this “anti-realist” theory about morality, as it is called, would cause great trouble for the interpretive account of law I defend. We would have to say something that seems crazy, which is that nothing we say about the law is true—or false either. That may be an attractive conclusion to reach in a philosophy seminar room, but not in a court of law. A judge who sentenced a defendant to jail while admitting that the judge’s own view of the law is only an emotional expression would probably be sent to jail himself.

Advertisement

So I had to take sides about this deep issue of moral theory. In an article in 1991, and then in a fuller version of that article in the first part of Justice for Hedgehogs, I argued that the “anti-realist” view is in fact incoherent. Consider the proposition that rich people have no moral duty to help the poor of their own community. If that proposition is not true, then it is not true that rich people have that duty, and that is itself a moral claim. If no moral claim can be true or false, then that one can’t be true either, so anti-realism is self-defeating.

Now that simple statement may seem too quick an argument, and in fact it took me many pages to explain it. I had to consider a great variety of metaphysical arguments, proposed by a great many very distinguished philosophers, for the position I called incoherent. I cannot attempt to summarize those arguments now, but only to emphasize that this excursion into metaphysics was not for me optional. It was required by way of defense of a theory of law, which was in turn required by politically very important positions I wished to defend in constitutional law. We cannot pick apart these various philosophical issues and call some of practical and others of only theoretical importance. Politics and philosophy are much too closely integrated for that.

Anti-realism in moral theory is premised on a more general theory of truth we might call “scientism.” This holds that the methods of the physical sciences provide the gold standard for any investigation, that only when these methods are available is it proper to speak of truth. According to scientism, once we see that moral argument is not amenable to scientific methods, we must abandon the idea that there is truth in morality. We must find some other account of moral discourse—that it is only nonsense or only emotional goading, for example. I rejected scientism, but I therefore needed another more general account of the idea of truth that showed scientific methods to be appropriate for the pursuit of truth in science but other methods to be appropriate to that pursuit in other intellectual departments.

This required a very abstract theory of truth. I present one in Justice for Hedgehogs. Following a particular understanding of the philosophy of Charles Sanders Peirce, I suggest defining truth, in the abstract, as success in inquiry, leaving further definition of truth as a substantive matter within different intellectual departments and so producing more distinct and tailored accounts of truth there. This merger of theories of truth with substantive theories that are different in different areas makes the world of truth safe for value.

However, even if I am right in all this, it establishes only that there is truth in morality and politics and therefore in law. It remains to ask what truth there is. What is a life well-lived? What duties do we owe as individuals to other individuals? What duties do we collectively owe to others in politics? What is justice? Liberty? Equality? Democracy? Yes, it is crucial to establish that there are, in principle, better and worse answers to these questions, and therefore a best answer and therefore a true answer. But only if we go further and try to identify, so far as we can, what these right, true answers really are. I suggested that this could not be done piecemeal, taking one duty or one political virtue at a time. We had to try to answer the great moral and political questions all together, the way we solve a complex series of simultaneous equations in mathematics.

I therefore proposed two fundamental principles that I believe can provide the most coherent and attractive answers to all these questions. First, that it is objectively important—important from everyone’s point of view—that each human life succeeds rather than fails: that people live well. Second, that each person has a fundamental, inalienable responsibility to take charge of his or her own life: that it is finally up to that person to decide what living well would mean and to pursue that life.

These may strike you as elitist and in any case, for most people, unrealizable demands. But in Justice for Hedgehogs I argued, to the contrary, that people in radically different economic and cultural situations can recognize that their lives are important and can recognize what their own responsibility to live well, in their own circumstances, means. I argued, relying on Immanuel Kant’s thesis that no one respects his own humanity who does not respect humanity in other people, that we can define what we owe to other people as part of what we owe to ourselves. The key is the idea of dignity: it belongs to our own dignity to respect the dignity of other people.

I could not, however, defend this account of personal and moral responsibility without recognizing the persistent and deep challenge to any theory of responsibility: the argument that people cannot be responsible because, in a deterministic universe, people have no free will, cannot actually make choices, and so cannot be responsible for choice. The so-called “free will” problem has been a threat to human responsibility for many centuries. I argued that it has been misunderstood: that the claim that we lack responsibility because we lack free will must be understood as an ethical and not a physical or metaphysical thesis, and that once the challenge is understood that way, the better answer is that people are morally responsible after all.1

That brings us to politics, and to the great political virtues. The concepts of justice, liberty, equality, and democracy are, like the concept of law, interpretive concepts. We argue about the right way to understand these concepts by arguing about how they should be understood given the crucial role they play in political discourse. I propose, again, that we should understand them as reflecting the two principles of dignity that I have argued are fundamental in private morality: these two principles form the spine of public political morality as well. And again we need to define them together so that they offer mutual support, not conflict. We achieve true economic equality, for example, not when everyone has the same wealth, no matter what decisions he has made in the course of his life, but when what one has depends only on those decisions, and not on good or bad luck in health, accident, or inheritance.

That idea of equality ties together the moral ideal of personal responsibility and the political ideals of distributive justice. But how can equality so understood be achieved in a real political economy when good and bad luck are facts of life? I proposed what I believe to be an economically sophisticated theory of taxation by way of answer: a redistributive tax system should be modeled on a hypothetical insurance scheme. The fortunate should pay, by way of taxes, what that model suggests they would have paid, by way of premiums, in an actual insurance market; the unfortunate should receive, by way of social benefits, what they would have been entitled to receive in that insurance market.2

I recognize that this account of the philosophical basis of economic equality is much too condensed. I have explained it at much greater length elsewhere, particularly in my book Sovereign Virtue (2000). My point, yet again, is only to suggest the interconnectedness among concrete legal issues, questions of personal ethics and morality, broad political issues of social policy, and the most abstract, rarefied philosophical and metaphysical puzzles. They can’t be separated, and my own career has been driven by their deep integration.

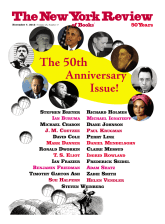

This Issue

November 7, 2013

Love in the Gardens

Gambling with Civilization

On Reading Proust