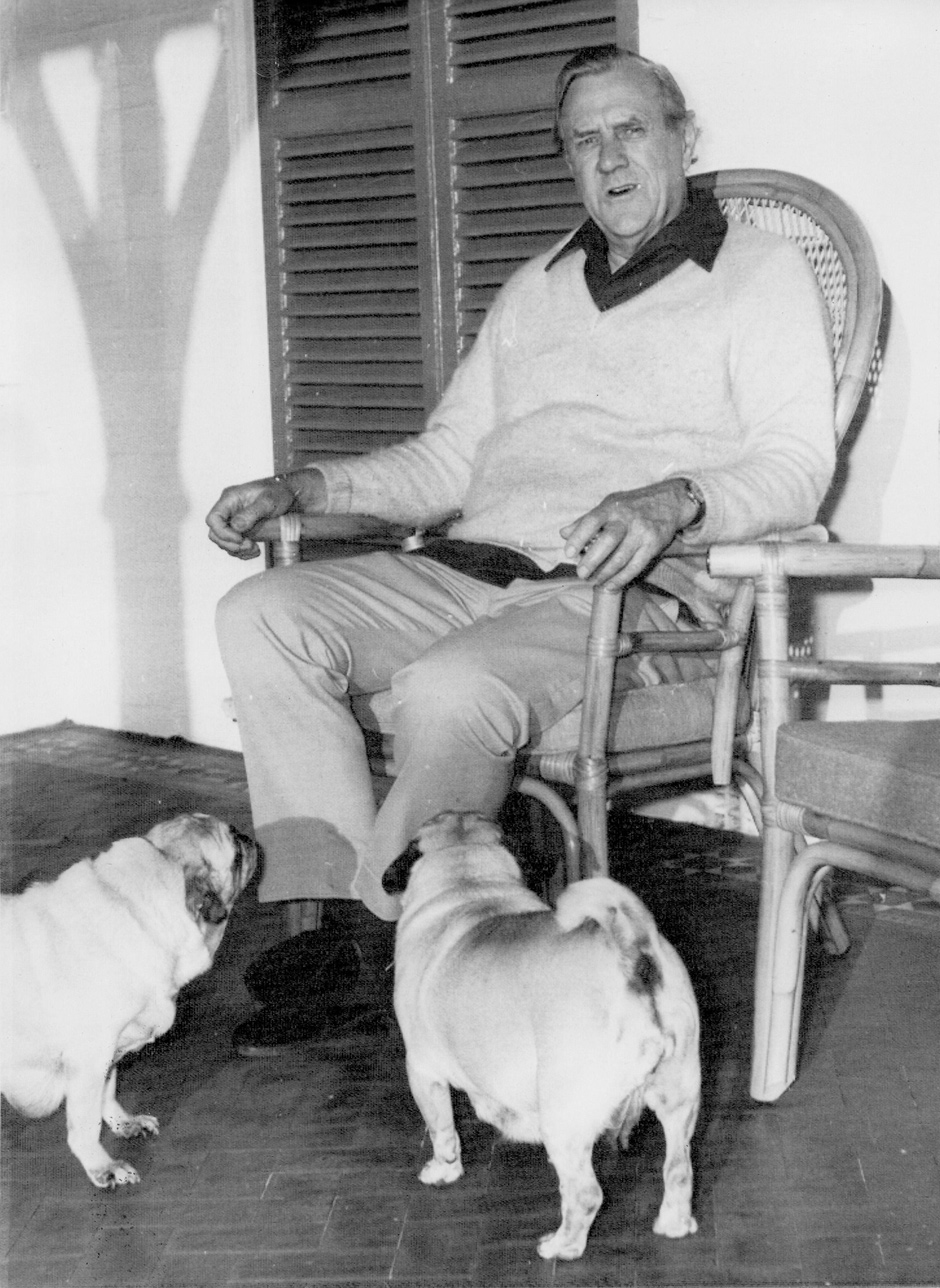

Patrick White is, on most counts, the greatest writer Australia has produced, though the sense in which that country produced him needs at once to be qualified—he had his schooling in England, studied at Cambridge University, spent his twenties as a young man about town in London, and during World War II served with the British armed forces. What Australia did provide him with was fortune, in the form of an early inheritance—the White family were wealthy graziers—substantial enough for him to live an independent life.

The nineteenth century was the heyday of the Great Writer. In our times the concept of greatness has fallen under suspicion, especially when attached to whiteness and maleness, and Great Writers courses have largely been retired from the college curriculum. But to call Patrick White a Great Writer—specifically a Great Writer in the Romantic mold—seems right, if only because he had the typically great-writerly sense of being marked out from birth for an uncommon destiny and granted a talent—not necessarily a welcome one—that it is death to hide, that talent consisting in the power to see, intermittently, flashes of the truth behind appearances.

The life arc of the kind of artist White felt himself to be is most clearly shown forth in Voss (1957), the novel that made his reputation. Johann Ulrich Voss sets off with a miscellaneous band of followers on a journey of exploration into the vast Australian outback. Most of the party die, including Voss himself; but in the course of their long march Voss makes discoveries about the human spirit in extremis that, by a kind of spiritual telepathy, he transmits to the beloved he has left behind in Sydney, and through her to us.

White’s sense of being special was closely tied to his homosexuality. He did not contest the verdict of the Australia of his day that homosexuality was “deviant,” but took his deviance as a blessing as much as a curse:

I see myself not so much a homosexual as a mind possessed by the spirit of man or woman according to actual situations or [sic] the characters I become in my writing…. Ambivalence has given me insights into human nature, denied, I believe, to those who are unequivocally male or female.

The award of the Nobel Prize in 1973 took many by surprise, particularly in Australia, where White was looked on as a difficult writer with a mannered, unnecessarily complex prose style. From a European perspective the award made more sense. White stood out from his Anglophone contemporaries in his familiarity with European Modernism (his Cambridge degree was in French and German). His language, and indeed his vision of the world, were indelibly marked by an early immersion in Expressionism, both literary and pictorial. His sensibility was always strongly visual. As a young man he moved among artists rather than among writers (he was an habitué of the studio of his close contemporary Francis Bacon), and often remarked that he wished he could have been a painter.

Between 1939 and 1979 White published eleven big novels. In the remaining years of his life, up to his death in 1990, he produced stories, plays, and memoirs, but no fiction on the previous grand scale. His health was declining. Since childhood he had suffered from asthma; in his last years he was flattened by severe respiratory attacks for which medical science could offer little help. His letters suggest that he doubted he had the staying power, and perhaps the will too, to bring off a substantial new work.

To an inquiry from the Australian National Library as to his plans for the disposition of his papers, he responded: “I can’t let you have my papers because I don’t keep any.” As for his manuscripts, he said, these were routinely destroyed once the book had appeared in print. “Anything [that is] unfinished when I die is to be burnt,” he concluded. And indeed, in his will he instructed his literary executor, his agent Barbara Mobbs, to destroy whatever papers he left behind.

Mobbs disobeyed that instruction. In 2006 she committed the surviving papers, a surprisingly large cache packed in thirty-two boxes, to the ANL. Researchers, including White’s biographer David Marr, have been busy with this Nachlaß ever since. Among the fruits of Marr’s labors we now have The Hanging Garden, a 50,000-word fragment of a novel that White commenced early in 1981 but then, after weeks of intense and productive labor, abandoned.

Marr has high praise for this resurrected fragment: “A masterpiece in the making,” he calls it. One can see why. Although it is only a draft, the creative intelligence behind the prose is as intense and the characterization as deft as anywhere in White. There is no sign at all of failing powers. The fragment, constituting the first third of the novel, is largely self-contained. All that is lacking is a sense of where the action is leading, what all the preparation is preparatory to.

Advertisement

After the initial burst of activity White never returned to The Hanging Garden. It joined two other abandoned novels among the papers that Mobbs was instructed to destroy; it is not inconceivable that these too will be resurrected and offered to the public at some future date.

The world is a richer place now that we have The Hanging Garden. But what of Patrick White himself, who made it clear that he did not want the world to see fragments of unachieved works from his hand? What would White say of Mobbs if he could speak from beyond the grave?

Perhaps the most notorious case of an executor countermanding the instructions of the deceased is provided by Max Brod, executor of the literary estate of his close friend Franz Kafka. Kafka, himself a trained lawyer, could not have spelled out his instructions more clearly:

Dearest Max, My last request: Everything I leave behind me…in the way of notebooks, manuscripts, letters, my own and other people’s, sketches and so on, is to be burned unread and to the last page, as well as all writings of mine or notes which either you may have or other people, from whom you are to beg them in my name. Letters which are not handed over to you should at least be faithfully burned by those who have them.

Yours, Franz Kafka.

Had Brod done his duty, we would have neither The Trial nor The Castle. As a result of his betrayal, the world is not just richer but metamorphosed, transfigured. Does the example of Brod and Kafka persuade us that literary executors, and perhaps executors in general, should be granted leeway to reinterpret instructions in the light of the general good?

There is an unstated prolegomenon to Kafka’s letter, as there is in most testamentary instructions of this kind: “By the time I am on my deathbed, and have to confront the fact that I will never be able to resume work on the fragments in my desk drawer, I will no longer be in a position to destroy them. Therefore I see no recourse but to ask you act on my behalf. Unable to compel you, I can only trust you to honor my request.”

In justifying his failure to “commit the incendiary act,” Brod named two grounds. The first was that Kafka’s standards for permitting his handiwork to see the light of day were unnaturally high: “the highest religious standards,” Brod called them. The second was more down to earth: though he had clearly told Kafka that he would not carry out his instructions, Kafka had not dismissed him as executor, therefore (Brod reasoned) in his heart Kafka must have known the manuscripts would not be destroyed.

In law, the words of a will are meant to express the full and final intention of the testator. Thus if the will is well constructed—that is to say, properly worded, in accordance with the formulaic language of testamentary tradition—then interpretation of the will will be a fairly mechanical matter: we need nothing more than a handbook of testamentary formulas to gain unambiguous access to the intention of the testator. In the Anglo-American legal system, the handbook of formulas is known as the rules of construction, and the tradition of interpretation based on them as the plain meaning doctrine.

The plain meaning doctrine has for a while been under siege. The essence of the critique was set forth over a century ago by the legal scholar John H. Wigmore:

The fallacy consists in assuming that there is or ever can be some one real or absolute meaning. In truth, there can be only some person’s meaning; and that person, whose meaning the law is seeking, is the writer of the document.

The unique difficulty posed by wills, one might add, is that the writer of the document, the person whose meaning the law is seeking, is by definition absent.

The relativistic approach to meaning expressed by Wigmore has the upper hand in many jurisdictions today. According to this approach, our energies should be directed in the first place to grasping the anterior intentions of the testator, and only secondarily to interpreting the written expression of those intentions in the light of precedent. Thus rules of construction no longer provide the last word; a more open attitude has come to prevail toward admitting extrinsic evidence of the testator’s intentions.

In 1999 the American Law Institute, in its Restatement of Property, Wills and Other Donative Transfers, went so far as to declare that the language of a document (such as a will) is “so colored by the circumstances surrounding its formulation that [other] evidence regarding the donor’s intention is always [my emphasis] relevant.” In this respect the ALI registers a shift of emphasis not only in US law but in the entire legal tradition founded on English law.

Advertisement

If the language of the testamentary document is always conditioned by, and may always be supplemented by, the circumstances surrounding its formulation, what circumstances can we imagine, surrounding instructions from a writer that his papers be destroyed, that might justify ignoring those instructions?

In the case of Brod and Kafka, aside from the circumstances adduced by Brod (that the testator had unrealistic standards for publication of his work; that the testator was aware that his executor could not be relied on), there is a third and more compelling one: that the testator could have had no reliable idea of the broad significance of his work.

Public opinion is, I would guess, solidly behind executors like Brod and Mobbs who refuse to carry out their testamentary instructions on the twofold grounds that they are in a better position than the deceased to see the broad significance of the work, and that considerations of the public good should trump the expressed wishes of the deceased. What then should a writer do if he truly, finally, and absolutely wants his papers to be destroyed? In the reigning legal climate, the best answer would seem to be: do the job yourself. Furthermore, do it early, before you are physically incapable. If you delay too long, you will have to instruct someone else to act on your behalf, and that person may decide that you do not truly, finally, and absolutely mean what you say.

The Hanging Gardens is the story of two European children evacuated for their safety to Australia during World War II. Young Gilbert Horsfall has been sent from London to escape the bombing. Eirene Sklavos, whose Greek father, a Communist, has died in prison, is brought to Sydney by her Australian mother, who then returns to the theater of war. The two children find themselves boarding with Mrs. Bulpit, a British-born widow.

During their first night alone at Mrs. Bulpit’s the children, whose ages are not given but who must be eleven or twelve, share a bedroom and, for most of the night, a bed. In Eirene there begins to grow an obsession with Gilbert in which inchoate sexual stirrings are mixed with an obscure realization that they are not just fellow aliens in a new land but two of a kind (yet of what kind?), brought together by fate. Of Gilbert’s feelings for Eirene we know less, in part because he is trapped in boyish male disdain for girls, in part (one guesses) because his realization of her importance in his life was intended to come later, in the body of the book that never got written.

The children make Mrs. Bulpit’s overgrown garden, on a cliff overlooking the bay, into a refuge from the crassness and tedium of life in their new country. In a huge old fig tree they build a tree house where they can hide out and practice intimacies that have more to do with physical curiosity than sexual desire.

After a year or two of Mrs. Bulpit’s increasingly distracted foster care, during which news arrives that Eirene’s mother has died in a bombing raid, there is a revolution in the children’s lives. Mrs. Bulpit succumbs to cancer, and they are farmed out, Gilbert to a prosperous accountant, Eirene to the home of her mother’s sister Mrs. Lockhart, where she has to fend off the groping hands of Mr. Lockhart and fight for some vestige of privacy from the loutish Lockhart boys. From Gilbert she receives a single letter, in which he hopes wistfully that he and she can stay in touch. Though she broods on memories of their time together in the garden overhanging the sea, they have no further contact. The fragment ends in mid-1945, with victory in Europe and the prospect that the two children will be returned to their native countries.

Greece and Australia constitute the opposing poles between which Eirene moves. Having just begun to get a feel for Greek politics and her parents’ position in Greek society (her father seems to have been a romantic leftist from an “old,” antimonarchist family), she must now navigate the very different Australian system, where she will be looked down on as a “reffo” (refugee) and suspected, because of her dark skin, of being a “black.” At school, her precocious acquaintance with Racine and Goethe will count against her (antiegalitarian, un-Australian).

White has a fascination much like Gustave Flaubert’s with the horrors of bad taste, instances of which he records meticulously. “I love plastic flowers, don’t you?” remarks the mother of one of Eirene’s classmates. “I think they’re more artistic than the real.” Mrs. Bulpit, with her racial animosities and her nostalgia for “the Old Country,” her secret drinking and her stomach-turning cooking, is a social type White pins down with Dickensian precision. Another type to come under scrutiny is the headmistress of an upmarket girls’ school, her spectacles “radiat[ing] the superior virtues of the pure-bred Anglo-Saxon upper class,” who interviews Eirene as a prospective student. Surprisingly, she accepts the little foreigner. Her motive becomes clearer when, later, she begins to caress the child suggestively.

Other minor characters are brought to life in a quick phrase or two: a teacher whose laugh “sounds rubbery, sticky, like a tyre on a bumpy road”; a girl who, according to schoolyard gossip, “laid down with a GI in the scrub… and he gave her a packet of cigarettes. She said it was immense.”

But the spiritual meanness of Australian society that White had anatomized in such earlier novels as Riders in the Chariot (1961) and The Solid Mandala (1966) is not the real focus of his concern in The Hanging Garden. Even the grotesque Mrs. Bulpit is allowed her relaxed moments. “I’m not all that gone on foreigners, but she’s a human being, isn’t she?” she says of Eirene; generally she does her best for the two children under her care without understanding either one in the least.

Several motifs that are sounded in the fragment hang in the air with little indication about how White meant to use them. One of these is the garden of the title, which seems destined to bear some symbolic weight but in the fragment is simply a place where the children go to get away from their keeper. Another is the shrunken head brought back from the Amazon by the father of a school friend of Eirene’s, which immediately enters her private world as a sacred talisman. But the most intriguing motif is the pneuma that Eirene remembers being spoken of on the island in the Cyclades where she spent a year with her father’s family. Pneuma, she tells Gilbert, cannot be explained in English. The truth is, she has only the vaguest of ideas herself. Pneuma is in fact one of the more mysterious forces in both ancient Greek and early Christian religion. Pneuma, issuing from deep in the earth, is what the oracle at Delphi inhales to give her the power of prophecy. In the New Testament pneuma is the wind that is also the breath of God:

The wind [pneuma] blows where it wishes and you hear the sound of it, but do not know where it comes from and where it is going; so it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit [pneuma].

Similarly, Jesus breathes on his disciples and says, “Receive the Holy Spirit [pneuma].”

Like the Panageia, the all-powerful mother goddess whom Eirene also recalls from her time on the island, pneuma belongs to the syncretic popular religion of rural Greece, fast vanishing in our day, a religion in which archaic elements survive embedded in Orthodox Christianity. White clearly intends pneuma to be more than a mere marker of Eirene’s Greek origins. Pneuma, Eirene obscurely feels, watches over Gilbert and her; White may well have intended it to foreshadow the breath or spirit that takes over the artist and speaks through him or her, and thereby hinted at what the future would hold for his two characters.

In Greece, Eirene reflects, memories are “burnt into you.” Not so in Australia. In Australia there is no sense of mortality: “Australians are only born to live.” At moments like these, Eirene becomes a mouthpiece for insights that do not realistically belong to an adolescent girl, however much possessed by pneuma. Whereas Eirene’s younger sensibility is represented in a mix of narrative modes, with interior monologue predominating, the narrative of her adolescence seems to confront White with troublesome technical difficulties. He makes her keep a diary, but then seems to be unsure whether her narration is identical with what she writes in the diary or whether it is some later, more mature elaboration of what she wrote there, or whether keeping a diary is simply girlish activity that has nothing to do with how her story is told. Of course we should not forget that what we are reading in The Hanging Garden is only a draft (according to Marr a second draft). But failure to find a plausible voice for the maturing Eirene may well be a sign that White was losing interest in the project as a whole.

White had a deep attachment to Greece, principally through Manoly Lascaris, whom he met and fell in love with in Alexandria during the war, and with whom he came to share the rest of his life. White’s 1981 memoir Flaws in the Glass contains a lengthy record of their travels together in Greece. For a period, he writes, he was “in the grip of a passionate love affair, not so much with Greece as the idea of it.” At one time he and Lascaris thought of buying a house on Patmos. “Greece is one long despairing rage in those who understand her, worse for Manoly because she is his, as Australia is worse for me because of my responsibility.” It is possible that through Gilbert (standing in for himself) and Eirene (standing in for Lascaris) he hoped, in The Hanging Garden, to explore more deeply feelings of despairing rage at a beloved country that has fallen into the hands of a brash, greedy, nouveau-riche class.

White explores sexual feeling between the two refugee children without false delicacy. Gilbert fights against giving in to his feelings for “this dark snake of a girl,” yet as he masturbates her image comes unsummoned, “standing over him looking down, prissy lips pressed together…haunting him.” He is baffled by Eirene’s power over him. “She was nothing to him, another kid, a girl, a Greek….” Yet when, years later, he writes his first letter to her, he calls the letter “a line from your fellow reffo,” as if to concede he has accepted their common destiny.

Eirene’s feelings for Gilbert are more complex, and indeed constitute the heart of the fragment. While she is still prepubertal, sexual interest in him is at war with fastidious distaste for his clumsy boy self. She has a dream in which he tears off her clothes in the school toilet and discloses not a “flower ringed with fur” but a “baby’s wrinkle,” to the jeers of the watching children. In other dreams, fragmentary memories crop up of witnessing her parents in a sexual embrace, of her mother’s flirtations with other men. In these dreams she figures as the excluded other, angry, helpless, the one who wants but is unwanted.

Then as she reaches sexual maturity her feelings grow less confused. On their last night before they are separated, the two go to bed together and are intimate without having sex in the usual sense of the term. Eirene is able to feel quite motherly toward the sleeping boy. She will look back on him as “almost part of myself, the one I have shared secrets with, the pneuma [which] I could not explain, but which he must understand.”

At her new school Eirene is adopted by a fashionable classmate named Trish. Trish confides that what engage her most are money and social success. What of Eirene? “Love I think is what I’m most interested in,” Eirene replies. Trish shrieks with laughter. “That’s not very ambitious Ireen you can have it any night of the week.” Eirene is mortified; yet even so, she is sure she is on the right track. Love, but more specifically “transcendence,” is what she is ultimately after. Whatever transcendence stands for, it seems to have no grip in the Australian landscape; yet

[I know] about it from experience almost in my cradle, anyway from stubbing my toes on Greek stones, from my face whipped by pine branches, from the smell of drying wax candles in old mouldy hill-side chapels…. Mountain snow stained with Greek blood. And the pneuma floating above, like a blue cloud in a blue sky.

Intimations such as these, hinting that she is in the world to transcend the world, mark Eirene as one of White’s elect, along with Voss and the four Riders in the Chariot and Waldo Brown in The Solid Mandala and Hurtle Duffield in The Vivisector: outsiders mocked by society yet doggedly occupied in their private quests for transcendence, or, as White more often calls it, the truth.

This Issue

November 7, 2013

Love in the Gardens

Gambling with Civilization

On Reading Proust