Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Maharaja Ranjit Singh in a Bazaar (detail), circa 1840–1845. Singh was the founder of the Sikh Empire in the Punjab in the early nineteenth century and the enemy of Dost Mohammad, whom the British hoped to replace as ruler of Afghanistan with their ally Shah Shuja.

After a journey through Central Asia in 1888, the young George Curzon concluded that British policy on Afghanistan was a farrago of inexplicable waywardness. For fifty years, wrote the future viceroy of India,

there has not been an Afghan Amir whom we have not alternately fought against and caressed, now repudiating and now recognising his sovereignty, now appealing to his subjects as their saviours, now slaughtering them as our foes….Small wonder that we have never been trusted by Afghan rulers, or liked by the Afghan people!1

The British position, he added, was “impregnable” in Asia except in Afghanistan, where it was “uniformly vulnerable.” How had this contrast occurred? Curzon hinted at the answer when he archly dedicated the book of his travels “to the great army of Russophobes who mislead others, and Russophiles whom others mislead.” The problem was Russia, or rather, British perceptions of the ambitions of Russia.

At the end of the eighteenth century there had been no problem because thousands of miles still separated the British and tsarist empires. But Napoleon Bonaparte had planned to attack the British in India, first via Egypt in alliance with Tipu Sultan, who ruled the South Indian kingdom of Mysore from 1782 to 1799, and later overland via Persia in concert with the Russians. Although the first plan was foiled by Nelson’s navy at the Battle of the Nile in 1798 and the second was dropped in favor of Napoleon’s march on Moscow, there remained—at least in British minds—a potential Russian threat to India. During the nineteenth century Russia expanded its borders to the south and east at a pace so rapid that it induced paranoia among British officials.2 They reacted by sending agents into the lands between the empires with instructions to counter Russian moves and bolster buffer states. An Anglo-Russian rivalry was created, and the Great Game was begun.

One of the measures taken by the British as a reaction to Napoleon’s second project was the dispatch of a delegation to Shah Shuja, the Afghan ruler, early in 1809. Alas, just as the two parties were agreeing on a treaty of alliance, Shuja was overthrown by rivals and his army defeated. After several years as an unhappy refugee, during which he was robbed and imprisoned by the Sikh ruler Ranjit Singh, he and his harem found asylum at the British garrison town of Ludhiana, in the Punjab. Over the following years Shuja dreamed and plotted his return to Kabul and made three unsuccessful attempts to regain his throne.

Yet despite his reputation as an unlucky loser, in 1839 the British government in India decided to help this now elderly exile to make a fourth effort. The decision was made chiefly by Lord Auckland, the governor general (as the viceroy was known before 1858), a man who knew little about India, and his chief adviser, Sir William Macnaghten, who knew almost nothing about Afghanistan. Confident that Shuja, whatever his defects, would be a pro-British and anti-Russian ruler, they were determined to eject the current Afghan leader, Dost Mohammad, and replace him with their protégé, if necessary using British troops. Their attempt to do so is the subject of William Dalrymple’s splendid and absorbing new book.3

More experienced and perceptive officials were incredulous when they heard what Auckland and Macnaghten proposed. Alexander Burnes, who had explored Afghanistan and Central Asia, urged them to back Dost Mohammad, an effective ruler keen for an alliance with the British. If he were overthrown, Burnes argued, he and his supporters would become allies of Russia and Persia. Others warned of the practical difficulties of an expedition to bring down Dost Mohammad. It might be easy to install Shuja in Kabul, said Mountstuart Elphinstone, the East India Company official who had led the original delegation, but “maintaining him in a poor, cold, strong and remote country, among a turbulent people like the Afghans,” seemed to him a “hopeless” task. The natives, who would be neutral to start with, would quickly become disaffected and pro-Russian.

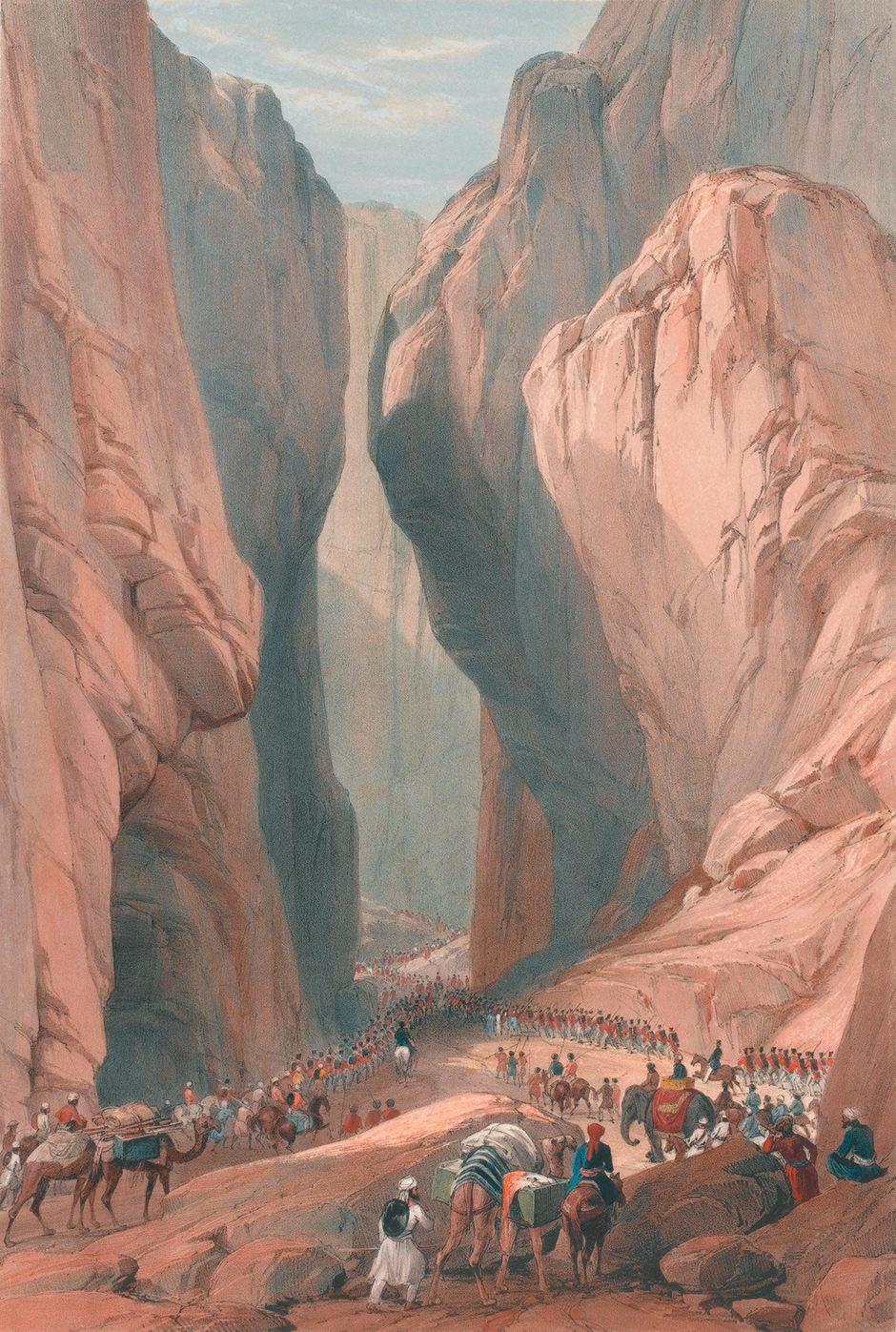

Auckland, swayed by Macnaghten, disregarded all such advice and ordered the invasion of Afghanistan at a time when Russia, despite playing “the game” by deploying the odd agent in Central Asia, presented no conceivable threat: its expansion had as yet got no further than the northern shores of the Caspian Sea. Auckland’s army, consisting of 1,000 European troops and 14,000 Indian sepoys, was formidable, and it traveled in style: it included a pack of foxhounds and three hundred camels to carry its wine cellar. The route, via Kandahar, presented such difficulties as salt marshes, where there was no water to drink, and narrow passes, from the tops of which tribesmen could fire or roll boulders down upon the invaders and their enormous array of camp followers.

Advertisement

Another impediment was the great Afghan fortress of Ghazni, an embarrassing problem because the state of the roads had persuaded the army to leave its siege guns two hundred miles to the rear. Enterprising sappers, however, were able to blow up a gate and make a breach, and the road to Kabul was soon open. Dost Mohammad fled, leaving the British and their friend Shuja to enter the capital unopposed. On New Year’s Eve Alexander Burnes (who despite his opposition to the invasion was now deputy to its political leader, Macnaghten) threw a party at which he appeared in his native dress of kilt and sporran.

Elphinstone had warned that it would be easy to get Shah Shuja to Kabul but difficult to keep him there, and the predictions of this wise and most civilized of officials were soon fulfilled. Yet the chief authors of the expedition’s woes were the British themselves, not the Afghans. Their army was substantial enough to take Kabul but insufficient to consolidate the new regime, especially when Auckland diverted some of its resources to another dubious military adventure, the Opium War against China. Nor were there enough funds to make the occupying army secure. Instead of building itself a defensible fort on a hill, it constructed a badly designed cantonment, or military camp, on a plain overlooked by the fortifications of various Afghan nobles. Auckland’s blunders did not end there. From the security of India he could see the costs but not the dangers of the occupation. He therefore ordered Macnaghten to reduce both the number of his troops and the subsidies needed to persuade tribal chiefs to keep open the passes that controlled his lines of communication.

On top of this, he made a ludicrous choice as the new commander-in-chief in Kabul. As Dalrymple points out, the British had one good general in Afghanistan, William Nott, who understood the country and was able to keep Kandahar, the area under his control, quiet throughout the occupation. Auckland obviously should have promoted him to overall command but because, according to Dalrymple, he found Nott “chippy and difficult and far from a gentleman,” he chose instead William Elphinstone (a cousin of Mountstuart), a sick and gouty major-general who had no experience of India and who had last seen action a quarter of a century earlier as commander of a regiment on the field of Waterloo.

Unlike Macnaghten, who remained complacent and imperceptive throughout, Nott was soon aware of the unpopularity of the invaders and realized they would be massacred unless reinforcements were sent. There had been isolated hostility from the beginning—British officers on fishing expeditions would suddenly be surrounded and murdered—but it was more than a year after the invasion that the Afghan “resistance” (Dalrymple’s term) launched its “jihad.” One of its main causes seems to have been the behavior of “licentious infidels,” British soldiers consorting with Afghan women. Particularly offensive was the amorous life of Burnes, who, according to hostile sources, was not content with his harem of Kashmiri ladies but coerced Afghan women as well. Whatever the truth of this, in November 1841 Burnes suddenly found himself attacked by a mob in his house in Kabul and, despite plucky resistance, he and his brother Charles were murdered.

The sequel to this incident is the strangest of all the strange things that happened (or did not happen) during these events. Although they had five thousand armed soldiers under their command on the plain, Macnaghten and Elphinstone did not try to rescue Burnes under siege in his house inside the city. (Shuja in his fortress at the Bala Hisar in Kabul was the only person who made any attempt to help him.) Even after his death they sent no troops to quell the riot, restore order, and bring back his body; they were simply too frightened. Instead of counterattacking, Macnaghten withdrew his forces into the camp, abandoning his treasury in the city, his food supplies, and the outlying forts.

Such pusillanimous behavior astonished Indians and Afghans alike. It was not how the British had acquitted themselves at Arcot under Robert Clive or at Assaye under the future Duke of Wellington—or indeed how they had performed the previous year at Ghazni. (Nor did it resemble their conduct of the future, in the Anglo-Sikh Wars or at Lucknow and Delhi in the Mutiny of 1857.) Their fearful inactivity, interrupted by one disastrous sortie, stimulated the resistance and assisted its recruitment.

In the long catalog of British blunders during the invasion, the most fatal was the decision to negotiate a withdrawal from Kabul in the middle of winter. Instead of moving their army into the fortifications of the Bala Hisar, which they could have made impregnable, the British leaders chose to withdraw through passes now manned by resentful and hostile tribesmen. Macnaghten duly rode out of the camp to negotiate the retreat and was promptly murdered by the chief Afghan commander, Akbar Khan (a son of Dost Mohammad), who had evidence that his adversary was plotting his assassination. Once again the British did not react, failing even to go out and retrieve Macnaghten’s corpse.

Advertisement

Despite friendly warnings by well-placed Afghans and Indians, General Elphinstone did not allow this incident to deflect him from negotiating a withdrawal. Consequently, in the January snows he marched his army out of the camp to its predictable annihilation. On the first afternoon it was forced to abandon its baggage by the Kabul River, and on subsequent days it stumbled from one ambush to another; marching in daylight along the most difficult route, the Kabul Gorge, made its soldiers easy targets for the tribesmen.

The column, which soon lost all cohesion, was followed closely by Akbar Khan, who repeatedly gave false assurances of safe conduct. So sophisticated was his duplicity that he ordered his men to “spare” the British in Dari (a language that many of his opponents knew) but to “slay them all” in Pashtu (an idiom that few of them understood). Eventually he agreed to “save” a small group of children, ladies, and wounded officers, whom he kept as hostages. The rest of the force struggled on, massacred in every defile, until Dr. William Brydon was left to stagger by himself into Jalalabad, a town near the Khyber Pass that was still held by a British garrison.

Akbar Khan and his army soon arrived outside Jalalabad, but his opponents there showed more pluck than he had come to expect. Under the command of Sir Robert “Fighting Bob” Sale, the starving British first managed to steal his flock of sheep and then inflicted a defeat that sent him and his army scurrying back to Kabul. By now the British in India had formed an “Army of Retribution” that marched into Afghanistan and was soon living up to its name. The thousands of bodies still lying unburied in the passes naturally acted as an incentive to revenge: one officer, who found the hacked and naked body of his brother with his genitals severed and stuffed in his mouth, became a hater of Muslims for the rest of his life. The consequences were foreseeable and appalling. Kabul was sacked and its bazaars destroyed before the vengeful force returned to the Khyber.

So what had been achieved after so much misery, so many deaths, and such widespread destruction? It is a question that subsequent invaders of Afghanistan—with similar experiences—must also have asked themselves. In this case—as in theirs—the answer ranges from “very little” to “nothing at all.” After Shah Shuja had been murdered by his godson, the British released Dost Mohammad (who had mysteriously surrendered to them) and in effect put him back on the throne from which they had taken so much trouble to remove him. It was a strange outcome, puzzling even to “the Dost,” who never understood “why the rulers of so great an empire should have gone across the Indus to deprive me of my poor and barren country.”

Many of the British, including the commander-in-chief in India, Sir Jasper Nicholls, were amazed and appalled by the folly of Auckland and Macnaghten. One of the sanest and most eloquent appraisals came from the army chaplain, the Reverend G.R. Gleig, who judged the invasion as

a war begun for no wise purpose, carried on with a strange mixture of rashness and timidity, brought to a close after suffering and disaster, without much glory attached either to the government which directed, or the great body of troops which waged it. Not one benefit, political or military, has been acquired with this war. Our eventual evacuation of the country resembled the retreat of an army defeated.

William Dalrymple tells this tragic story with verve, skill, and—unexpectedly in the circumstances—some humor. Using unknown or underused sources from India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, he recounts the tale from both sides, shifting the scenes, using eyewitness accounts, quoting at length heroic epic poems (originally written in Persian). These might not be the most reliable historical evidence but they certainly add color and vividness to the text. In an era of so much earnest, turgid postcolonial writing, it is rather a relief to read an exciting and somewhat old-fashioned narrative. The author has such a good sense of place and such a fine sense of adventure that sometimes one feels one could be reading John Buchan. And his prose, too, is reminiscent of previous generations. British officials (especially Macnaghten) are described as “pompous,” “snobbish,” “pernickety,” and “cantankerous,” while their wives are “bossy,” “waspish,” and “demanding.” Yet the best officers are “tough,” “resourceful,” “dashing,” and even “dashingly moustachioed.” Good Afghans are also “dashing,” as well as “honourable,” “cultured,” and “sophisticated,” but bad ones are “wily,” “slippery,” “cunning,” and “unscrupulous.” Here we seem to be in a pre-Freudian age of characterization.

Dalrymple is not an academic or indeed a natural scholar. A successful and well-known travel writer who has turned himself into a successful and well-known historian, he is an unusual and interesting person. Like his talented wife, the artist Olivia Fraser, he comes from a prominent Scottish family whose members often had careers in the East India Company. Admitting elsewhere that he comes from a class and a culture that have had their day—and a country too that is in relative decline—he chose long ago to live in Delhi. Like Buchan and many another adventurous Scot, he found Scotland too small and narrow (and cold) to live in. In India he has not quite (as our ancestors would have put it) “gone native” (he does not have the linguistic skills of such polyglots as Richard Burton) but he goes fairly close. He wears Indian clothes, likes Indian art, and promotes Sufi culture. He is in fact a rather eighteenth-century figure, ebullient and self-confident. One can imagine him in the old days of the East India Company with a hookah, a turban, and (if it weren’t for Olivia) a troupe of nautch girls.

His life and career in Asia have made Dalrymple not just a chronicler of the British-Indian past. He is also an active commentator on current affairs with strong views, for example, on the sufferings of the Palestinians or the preservation of Buddhist archaeological sites. In this book he does not continue his account of Britain’s Great Game, with its contest between Russophobes such as Lord Palmerston, who wanted to fight the tsarists in central Asia, and their wiser fellow countrymen, who realized that a Russian army that had marched to India via Afghanistan would be in no fit state to fight the Raj.

Nor does he describe Britain’s second invasion of Afghanistan—the fiasco of 1878–1880, redeemed partly at its end when a pro-Russian amir was turned into a British ally—or the third in 1919 (when Britain was not the aggressor). He says very little of the Russian invasion of 1979 and the occupation that lasted nine years. But he writes perceptively about the parallels between the war fought by Britain against Dost Mohammad and the war being waged today against the Taliban by America and its allies.

Tribal issues and political geography are still important. So is symbolism. In 1996 the Taliban’s Mullah Omar went to Kandahar, received the title “Commander of the Faithful,” and swathed himself in a cloth allegedly worn by the Prophet Mohammad. In doing so, he was taking his cue from Dost Mohammad 150 years earlier. On the invading side the parallels are less appealing but dishearteningly close: in both cases it was the bellicose and ill-informed who prevailed over calmer folk to instigate a war they had no idea how to end.

The similarities are of course not exact. Dalrymple makes no reference to Osama bin Laden, al-Qaeda, and the twin towers of Manhattan. But there is today a terrible sense of déjà vu. In each of the wars fought by Britain, Russia, and America, ignorant political hawks have claimed, against the accumulated evidence, that Afghanistan can be conquered on conventional battlefields. It never has, and it probably never will be. Whether or not it should matter so much to other countries who rules Afghanistan—and frankly it doesn’t—history has shown that ultimately the people will overcome their conquerors. They will tolerate puppet rulers for no more than a few years.

In carrying out his research for this fine book, Dalrymple traveled in Afghanistan and talked to many people. His experiences there convinced him that the lessons of history have regrettably not yet been learned and that as a result

the west’s fourth war in the country looks certain to end with as few political gains as the first three, and like them to terminate in an embarrassing withdrawal after a humiliating defeat, with Afghanistan yet again left in tribal chaos and quite possibly ruled by the same government which the war was originally fought to overthrow.

-

1

George Curzon, Russia in Central Asia in 1889 (Frank Cass, 1967), p. 356. ↩

-

2

In 1914 the great arctic explorer Fridjtof Nansen calculated that the Russian Empire had been expanding over four centuries at an average daily rate of fifty-five square miles, or more than 20,000 square miles a year. During the nineteenth century the growth of the British Empire was even faster, increasing at an average annual rate of some 100,000 square miles.

Most of this expansion took place in Canada, Africa, and Australia, but in the 1840s British India extended its frontiers to the northwest by the absorption of Sind and the Punjab. By the end of the century the two empires had outposts barely a dozen miles apart on the northwestern frontier. ↩

-

3

The book is also an attempted rehabilitation of Shuja. Although “a deeply flawed man [who] made many errors of judgement,” Dalrymple praises him as a “sophisticated and highly intelligent” figure, “resolute, brave and unbreakable.” ↩