1.

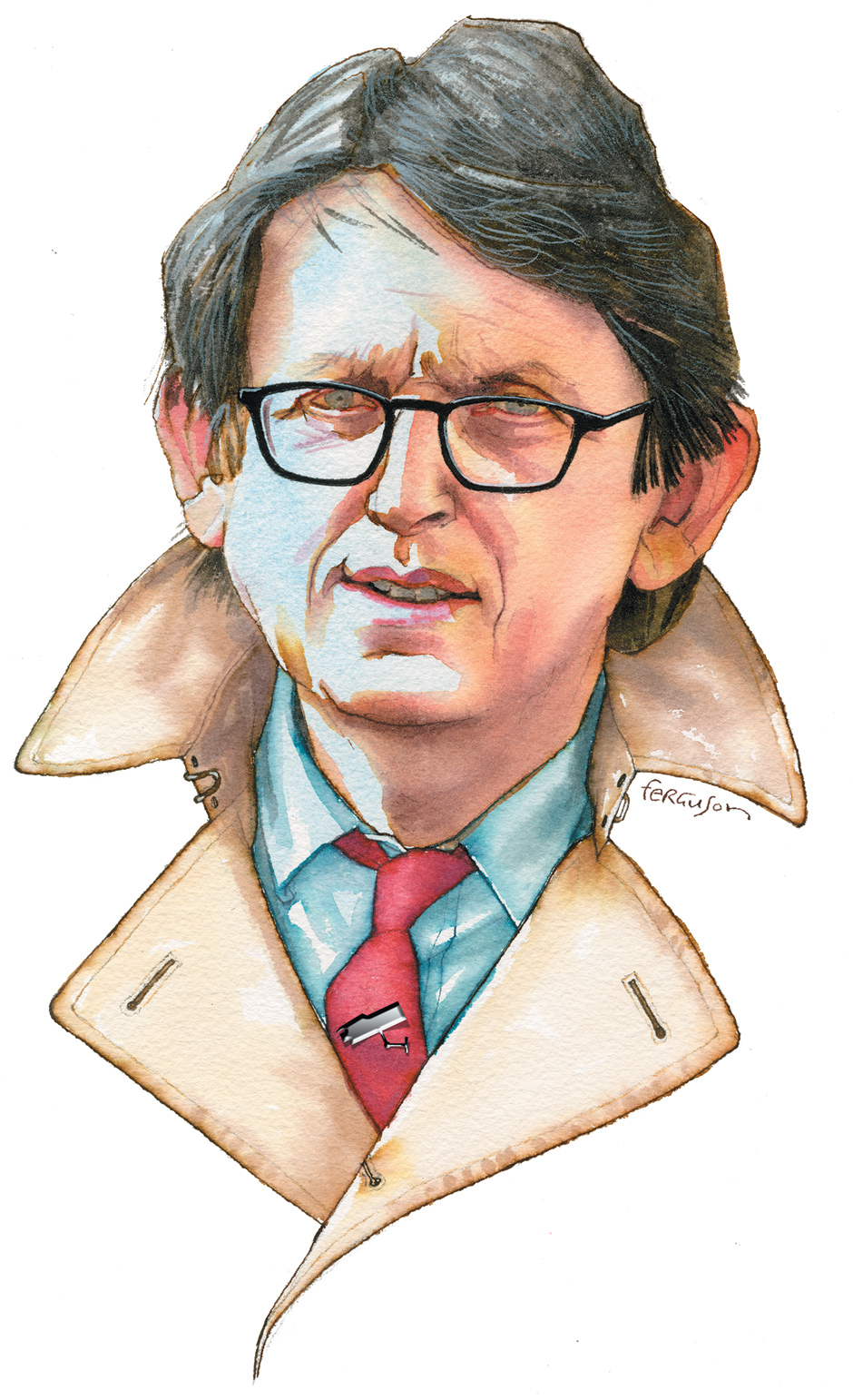

It is harder than you might think to destroy an Apple MacBook Pro according to British government standards. In a perfect world the officials who want to destroy such machines prefer them to be dropped into a kind of giant food mixer that reduces them to dust. Lacking such equipment, The Guardian purchased a power drill and angle grinder on July 20 this year and—under the watchful eyes of two state observers—ripped them into obsolescence.

It was hot, dusty work in the basement of The Guardian that Saturday, a date that surely merits some sort of footnote in any history of how, in modern democracies, governments tangle with the press. The British state had decreed that there had been “enough” debate around the material leaked in late May by the former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. If The Guardian refused to hand back or destroy the documents, I, as editor of The Guardian, could expect either an injunction or a visit by the police—it was never quite spelled out which. The state, in any event, was threatening prior restraint of reporting and discussion by the press, no matter its public interest or importance. This was par for the course in eighteenth-century Britain, less so now.

In our discussions with government officials before July 20 we had tried to impress on them that, apart from being wrong in principle, this attempt at gagging a news organization was fruitless. There were, we told them, further copies of the Snowden material in other countries. We explained that The Guardian was collaborating with news organizations in America. Glenn Greenwald, the journalist who first dealt with Snowden, lived in Rio. The filmmaker Laura Poitras, who had also been in contact with the former NSA analyst, had more material in Berlin. What did they imagine they were achieving by smashing up a few hard drives in London?

The government men said they were “painfully aware” that other copies existed, but their instructions were to close down the Guardian operation in London by destroying the computers containing information from Snowden. At some level I suspect our interlocutors realized that the game had changed. The technology that so excites the spooks—that gives them an all-seeing eye into billions of lives—is also technology that is virtually impossible to control or contain. But old habits die hard—hence the appeal of using the courts to stop publication. Both the 1917 US Espionage Act and the 1911 British Official Secrets Act—each with roots in wartime sedition and spy fever—cast a long shadow.

America has its own difficulties with journalists and their sources. But it is, nevertheless, a kinder environment for anyone trying to inform the sort of public debate regarding security and privacy that, post-Snowden at least, everyone seems to agree is desirable. The main advantage in the US is that it is, I hope, unthinkable that the American government would try to prevent publication in advance. A written constitution, the First Amendment, and the Supreme Court judgment in the Pentagon Papers case in 1971 have all played their part in establishing protections that are lacking in the UK. Jill Abramson, executive editor of The New York Times, is not going to be buying drills and angle grinders anytime soon.

And so the reporting goes on, much of it edited out of New York, as before, by our US editor, Janine Gibson. What’s gradually being revealed is that in the last ten or so years the US and UK governments, working in close collaboration, have been seeking to put entire populations under some form of surveillance. The apparent aim is to be able to collect and store “all the signals all the time”—that means all digital life, including Internet searches and all the phone calls, texts, and e-mails we make and send each other.

Some of it is data, some of it is so-called metadata—information about who sent a communication to whom, from where to where, not about specific contents. But as Stewart Baker, the former general counsel of the NSA, said in a recent discussion in New York, these are tricky distinctions. “Metadata absolutely tells you everything about somebody’s life,” he said with admirable candor. “If you have enough metadata you don’t really need content…. [It’s] sort of embarrassing how predictable we are as human beings.”

We have begun to glimpse how it’s all being done. The NSA and its British counterpart, GCHQ (Government Communication Headquarters), work closely with Internet service providers and telecom companies to amass enormous quantities of data on us. Some of it is done through the front door—formal legal requests. Some of it is done “upstream” of tech companies and phone companies—i.e., intercepting signals in transit. The agencies have attached probes to transatlantic cables, enabling them to vacuum up data on millions of users on both sides of the Atlantic. By last year GCHQ was handling 600 million “telephone events” each day, had tapped more than two hundred fiber optic cables, and was able to process data from at least forty-six of them at a time.

Advertisement

We have also learned about how the agencies have spent vast sums of money on subverting the integrity of the Internet itself—weakening its overall security in ways that ought to concern every individual, public body, or company that uses it. A trapdoor that lets the NSA into your messages is, most cryptologists agree, quite exploitable by others. If you’re anxious about your bank details or medical records sitting online, you’re probably right to be.

If, say, the Chinese had behaved like this toward the Internet and toward social platforms used around the world, there would be barely contained fury in the West. Little wonder that Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg was not impressed by President Obama’s repeated assurances that “there is no spying on Americans.” That was, he pointed out, of little comfort to American entrepreneurs trying to build global businesses.

All this is a very long way from the origins of the modern intelligence agencies, many of which, like the official secrecy laws protecting them, are around a hundred years old. In the UK, it began with shoe leather—trying to catch German spies snooping around shipyards. Within a very short time spies were trying to tap into the new Marconi wireless signals. Contemporary papers show a profound ignorance among officials and parliamentarians about emerging technologies. The same is undoubtedly true today.

For most of the twentieth century our imagination of what spies did owed much to Ian Fleming, John le Carré, or Robert Ludlum. It was, for much of the time, a world of spy against spy. Insofar as any technology was involved it involved gadgetry—gyro rocket guns, fake fingerprints, stun gas cigarettes, or exploding toothpaste.

Our imagination can’t help being colored by George Orwell, who didn’t write spy novels but did conjure up a horribly unsettling vision of how all-seeing technologies could lead societies into very dark places. Much more recently, the German film The Lives of Others gave a nightmarish insight into what horrors the East German Stasi was able to inflict on civilians with the technologies available to it in the 1980s. Henry Porter’s 2009 novel The Dying Light was prescient in describing a world of UK surveillance that he had taken pains to investigate.

Edward Snowden, a twenty-nine-year-old NSA contractor living in Hawaii, had a more contemporary ringside seat on the reality of what intelligence agencies actually now do—and it has little in common with the world of 007 or George Smiley. He had access to millions of highly classified documents and briefings from both the NSA and GCHQ. What he saw evidently disturbed him deeply. “Even if you’re not doing anything wrong you’re being watched and recorded,” he told The Guardian when he unmasked himself as the leaker of the material in early June. In a video interview he said:

The storage capability of these systems increases every year consistently by orders of magnitude to where it’s getting to the point—you don’t have to have done anything wrong. You simply have to eventually fall under suspicion from somebody, even by a wrong call. And then they can use this system to go back in time and scrutinize every decision you’ve ever made, every friend you’ve ever discussed something with. And attack you on that basis to sort of derive suspicion from an innocent life and paint anyone in the context of a wrongdoer.

He added, by way of explaining his own decision to blow the whistle, with all the foreseeable consequences for the rest of his life: “You realize that that’s the world you helped create and it’s gonna get worse with the next generation and the next generation who extend the capabilities of this sort of architecture of oppression.”

In Snowden’s view, the traditional forms of oversight—secret one-sided courts and closed congressional or parliamentary committees—are inadequate, not least because they have only partial information and poor technical understanding and are frequently misled. He may have had in mind such moments as when Director of National Intelligence James Clapper told Congress in March that the NSA did not intentionally collect “any type of data at all” on millions of Americans. That turned out not to be true. Clapper later justified his response as the “least untruthful answer” he could give. Which Orwell would surely have regarded as a doubleplusgood answer.

Lacking confidence in the courts or Congress, Snowden approached the other people who, in any modern democracy, are there to uncover truth, host debates, and hold people to account—journalists. When Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers just over forty years ago he or his representatives went to The Washington Post and The New York Times. These days whistleblowers are spoiled for choice. They don’t, in fact, need to “go” anywhere: they can simply publish themselves. We can only speculate about Snowden’s thinking as he prepared to leak the biggest cache of top secret material ever seen to Greenwald, Poitras, and The Guardian. But he may have thought something like this:

Advertisement

• The material will be highly complex to outsiders. It will take a team of people thousands of hours to reveal the full texture of what I want the world to understand. Serious mainstream newspapers sometimes do that kind of thing quite well.

• But I want this to be handled by people who are passionately, obsessively interested in this subject. People who will realize its true significance, who grasp the legal and political background, and who can return repeatedly and forensically to the subject in depth and at length. That’s what bloggers and specialist documentary makers can do well.

• The material is so secret and revelatory that any single news organization will come under immense pressure, up to and including criminal, legal, and government threats, not to publish it, or even to hand it back. Newspapers have in the past caved in to pressure, or sat on confidential documents for months or even years. So I will ensure that more than one news organization gets to see it.

• Geographical spread. Given the likely legal threats and government pressure, the ideal scenario would be to have the documents in more than one country. A prominent “outsider” newspaper with a history of investigative journalism would be interesting.

Whatever his actual reasoning, we know that Snowden chose rather cleverly. He came, via Greenwald, to The Guardian, a news organization with a huge audience (now the third-largest English-language readership in the world) and a track record of taking on some formidable organizations and individuals. He shared other documents with The Washington Post’s Barton Gellman. And he also involved two journalists—Greenwald and Poitras—who not only lived outside America but came from a completely different kind of journalistic tradition.

The Guardian itself inhabits an editorial space that is quite distinct from most American newspapers. British papers have grown up with less reverence for the notions of objectivity and detachment that can, rightly or wrongly, preoccupy some of our American colleagues. The paper started as The Manchester Guardian—an outsider to the sometimes cozy world of Fleet Street. Though it’s long since dropped “Manchester” from its masthead, its mentality is still that of the outsider—and it’s fair to say that it is regarded by some British journalists with the sort of distrust that members of a club feel about visitors.

We have also taken a different view of the new digital technologies that are so radically disrupting existing editorial and commercial models. We have, I think, been more receptive to the argument that newspapers can give a better account of the world by bringing together the multiple voices—by no means all of them conventional journalists—who now publish on many different platforms and in a great variety of styles.

That’s how Greenwald ended up on The Guardian. We were intrigued by this often erudite, sometimes combative lawyer-turned-blogger who had built up a considerable following of his own by repeatedly delving into issues having to do with privacy, civil liberties, war, and technology. Some reached for the smelling salts at what they dismissed as “activism” or “advocacy journalism.” We didn’t.

The recently released Dreamworks film about Julian Assange and WikiLeaks is cutely called The Fifth Estate, conjuring up a quasi-formal status for the new forms of digital publishing that now exist well beyond the familiar boundaries of the Fourth Estate. Greenwald does not much like being described as a member of the Fifth Estate—largely because there’s a persistent attempt by people in politics and law as well as journalism to limit protections (for example, over sources or secrets) to people they regard (but struggle to define) as bona fide journalists. But he recognizably does have a foot in each camp, old and new.

Bill Keller, former executive editor of The New York Times, confirmed to The New Yorker this month that his paper would have behaved differently from The Guardian in relation to Snowden:

If one of our columnists had come up with a story of that magnitude—something that could not be contained in a column—we would have turned it over to the newsroom reporting staff. And we would say in the story, “Nick Kristof obtained these documents.” But we would not have Nick Kristof write the story for the front page of The New York Times.

Well, we have also had our newsroom reporters working on the Snowden documents. But we did not ban Greenwald from appearing in the news pages. Quite apart from not making use of Greenwald’s forensic skills and accumulated knowledge, such a demarcation would have consigned him to the role of a mere supplier of secret material, with all the inherent potential legal risks to him and without any protection as a writer for the piece.

The irony is that it’s highly unlikely that Bill Keller would ever have faced this dilemma. Snowden—deliberately, it seems—did not give the documents to The New York Times, and it is certain that Greenwald would never have agreed to the Keller ground rules. None of this is to detract from the tough, admirable work The New York Times and others have done on the Snowden material. And vice versa, some British editors have come close to saying that it is not a journalist’s role to challenge the security services. But it does help explain how Greenwald—who has just announced he is leaving The Guardian to form a new philanthropic-funded independent Web-based reporting consortium—came to be in receipt of the biggest leak of intelligence in history. This venture, amply endowed with $250 million by a Silicon Valley billionaire, will be fascinating to watch. It takes little to imagine that it will be eyed with some anxiety by the top echelons of the NSA and GCHQ. This, some of them will be thinking, is a new media venture out of their nightmares.

2.

But back to the basement of The Guardian and the hot, messy work of destroying a computer. Why were we there?

A plausible answer is the one that the government advanced: that it was not safe for The Guardian to be examining highly secret documents in a newspaper office, no matter what precautions we took. We were, in fact, sympathetic to this argument: we were not keen on accidental leakage either. The government officials who lectured us appeared blissfully blind to the irony (another one!) that the only organization that had provably lost control of the data was not a newspaper, but the NSA. One official rolled his eyes at the thought of 850,000 people having access to it.

But one has to ask why, if this was of such overwhelming importance, it took the state’s best security people five weeks to arrive at The Guardian’s offices. And why—nearly three months later—no one from the official world has “made safe” the New York Times cache of documents obtained from The Guardian, never mind contacting Greenwald, Poitras, ProPublica, or The Guardian’s New York office.

A more plausible answer is that the British intelligence services simply find it extremely difficult to deal with journalists. Which, in itself, is illustrative of the wider problem of balancing surveillance with civil liberties. How on earth do you reconcile something that must be secret with something that begs to be discussed?

Until comparatively recently it was forbidden to name the heads of the UK intelligence services. The British press then had a voluntary compact—the Defence Advisory (DA) Notice system—under which editors can unofficially seek advice on security matters. The retired air force wing commander who administers it says that between 80 and 90 percent of journalists are happy to submit their copy to him in advance of publication.

The two main intelligence agencies, MI5 and MI6, will never comment on the record and typically prefer to deal with one or two journalists in each news organization—always on an unattributable basis. I have known them to refuse to deal with a particular reporter who wrote what they considered to be unsatisfactory stories. GCHQ is even less at ease in dealing with the press. The NSA was happy recently to speak to Der Spiegel. Not so GCHQ. In eighteen years as editor I have never once (knowingly) met any official from the Cheltenham-based agency.

The head of one of the other agencies once told me: “We’re a secret organization. There’s nothing in it for us in being more open about what we do. We see no need to change.”

This desire to play with cards tightly hugged to the chest seems to permeate government and even the British National Security Council (NSC)—a weekly meeting chaired by the prime minister that describes itself as “the main forum for collective discussion of the government’s objectives for national security.”

According to the Liberal Democrat former cabinet minister Chris Huhne, neither the cabinet nor the NSC was informed about the Prism and Tempora programs revealed by Edward Snowden. “The cabinet was told nothing about…their extraordinary capability to vacuum up and store personal emails, voice contact, social networking activity and even internet searches,” he recently wrote in The Guardian.

Huhne’s bafflement at reading in the newspapers secrets he was denied in government was all the greater because he had been party to other discussions relating to another “super-surveillance project”—a communications data bill, of which more below. “Maybe,” he speculated, “the securicrats thought that £1.8 billion was a modest price to duplicate what they were already doing.”

As the Snowden revelations proceeded it became apparent how reliant the security services actually are on the commercial services we all use—the Internet service providers, phone companies, and social networks—for help, both official and unofficial. Both in the US and in the UK the cloak of legal secrecy that surrounds this activity is such that no company dares come out openly and discuss its relations with the secret services. It is illegal to do so. For their part, governments on both sides of the Atlantic are terrified that commercial companies will “run for the hills” if consumers learn quite how accommodating they have been with their data.

But I did have an interesting (unattributable, of course) briefing from someone very senior in one West Coast mega-corporation who conceded that neither he nor the CEO of his company had security clearance to know what arrangements his own organization had reached with the US government. “So, it’s like a company within a company?” I asked. He waved his hand dismissively: “I know the guy, I trust him.”

There is quite a lot of trust involved in the world on which Edward Snowden has pulled back the curtain. Anyone using this particular company’s services has to trust a nameless man (not the CEO) to have a relationship of integrity with his government (which may not be the customer’s own government). Other documents we have seen say that some telecom companies go “well beyond” what they’re legally required to do. And in the UK we have to trust a government committee whose members are themselves not trusted to know about the most significant surveillance programs of all.

Little wonder, then, that the state sends its officials around to newspaper offices to try to persuade editors to keep the lid on all this stuff. The arguments are the ones you would expect them to use: you’ll have blood on your hands because our world “is going dark.”

The “going dark” argument was very expertly dissected by Peter Swire, who served as White House chief privacy counselor under President Clinton and is now on President Obama’s review panel of the NSA. In an essay published in 2011 he points out that the FBI and NSA have been protesting about losing surveillance capabilities—through greater encryption of the Internet—since the 1990s.

After explaining why encryption is “vital to economic growth, individual creativity, government operations, and numerous other goals,” Swire invites Americans to treat such protests from government agencies with some skepticism:

Due to changing technology, there are indeed specific ways that law enforcement and national security agencies lose specific previous capabilities. These specific losses, however, are more than offset by massive gains. Public debates should recognize that we are truly in a golden age of surveillance. By understanding that, we can reject calls for bad encryption policy. More generally, we should critically assess a wide range of proposals, and build a more secure computing and communications infrastructure.

So speaks an expert on Internet encryption. A recent Economist editorial also saw the alarming significance of NSA policies weakening the integrity of the Internet itself:

Any deliberate subversion of cryptographic systems by the NSA is simply a bad idea, and should stop. That would make life harder for the [official government] spooks, true, but there are plenty of other more targeted techniques they can use that do not reduce the security of the internet for all of its users, damage the reputation of America’s technology industry and leave its government looking untrustworthy and hypocritical.

I have a confession to make: I did not myself spot that story—of how law enforcement agencies are trying to undermine private encryption capacities—that was nested in the GCHQ/NSA documents; and even when it was explained to me by the young specialist technology reporters who did grasp its significance, I did not immediately understand it. Embarrassingly, I had to sketch a childlike drawing to confirm what I thought Jeff Larson, a Web developer and reporter at ProPublica, and James Ball, our own twenty-seven-year-old reporter and technical whiz kid, were telling me.

Do MPs and congressmen have any more sophisticated idea of what technology is now capable of? Could they, as supposed regulators, also decipher such documents? A couple of weeks ago I asked the question of another very senior member of the British cabinet who had followed the Snowden stories only hazily and whose main experience of intelligence seemed to date back to the 1970s. “The trouble with MPs,” he admitted, “is most of us don’t really understand the Internet.”

We’re back to trust. In the absence of newspapers to find, analyze, and explain this sort of thing, we have to rely on parliamentary and congressional oversight committees or secret, one-sided courts to do the job for us. In the US we are very much in the hands of Senator Dianne Feinstein and, in the UK, Malcolm Rifkind, a former defense secretary. Neither is, to put it mildly, a child of the digital age. I may be doing Feinstein and Rifkind a disservice, but I suspect they would have struggled to understand the documents that Jeff deciphered, with or without my drawing to help them. There are echoes, a hundred years later, of the Whitehall bureaucrats trying to get their heads around Marconi’s wireless signals.

Snowden’s documents show that the NSA and GCHQ employ extremely talented engineers who are ever more inventive in trying to dream up ever more exotic ways of keeping tabs on countless millions of people. To question, still less write about, their methods invites the standard response that one is giving away the game to the enemy. The spooks insist they work within the law. They will patiently explain the difference between a haystack—which they must be allowed to store—and a needle, which they can search for only under controlled circumstances.

No one is in any doubt that their work is essential. We need capable intelligence agencies. Liberal democracies do have determined and resourceful enemies. There is plainly a tension between the secrecy required in much intelligence work and the transparency that, in all else, democracy demands. Careful, responsible journalism is also necessary. The Guardian, The Washington Post, ProPublica, and The New York Times have gone to exceptional lengths to edit the Snowden material with caution. In private—but inevitably not in public—people familiar with the nature of the documents concede this. (It is worth noting that in a recent interview with The New York Times Snowden denied taking documents with him to Russia, adding, “There is zero percent chance the Russians or Chinese have received any documents.” Reuters recently confirmed that US officials have no proof that any of Snowden’s material has leaked to either country.)

The reason this overall issue matters is that, as technology develops, the police and intelligence agencies (and others) will always want more, and bigger, haystacks—and the ability to keep them longer. And the ability to create astonishingly powerful algorithms to find the needles.

In the UK there is, as mentioned, another government surveillance program waiting in the wings—but thankfully stalled at present—that would give the home secretary sweeping powers to order the retention of any kind of communications or metadata by any communications provider (CSP) for up to twelve months. This includes, for the first time, details of messages sent on social media, webmail, Skype and other calls over the Internet, and gaming sites as well as tracking all e-mail, text, and phone use. It would include who sent what to whom from where at what time.

Under the proposals the police, security services, tax authorities, and several other public bodies would not need any warrant to require the CSPs to hand over the data. The wording of the bill is intended to “future proof” other forms of technology. And all this is on top of what GCHQ already does. A number of senior British politicians have recently protested that they were kept in the dark about the intelligence agencies’ capacity, complaining that it was kept dark even from those charged with scrutinizing the pleas for even more intrusive capabilities.

Without some sort of wider debate now, it’s difficult to see what would restrict the intelligence business from asking for more. It’s estimated that there are around five million CCTV cameras in the UK. It is surely only a matter of time before someone suggests hooking these cameras up to facial recognition software (of the sort that even Google currently fears to release) and perhaps also switching on street microphones so they can pick up conversations, too.

It would—they would plausibly argue—help the good guys keep track of the bad guys and perhaps stop another terrorist outrage on British soil. And someone will surely tell a future editor: “Write about it and you could have blood on your hands. Terrorists will start to avoid main roads and other places with CCTV. Our world will go dark.”

Talented engineers will always be ahead of the laws. It was telling how dismayed the author of the Patriot Act, Congressman Jim Sensenbrenner, was by The Guardian’s revelations of top secret orders to collect all calls made by Verizon subscribers. That was not, he said, what he intended twelve years ago when he was drafting the act. He immediately wrote to Attorney General Eric Holder protesting: “I am extremely troubled by the FBI’s interpretation of this legislation…. Seizing phone records of millions of innocent people is excessive and un-American.”

Why, so far as we know, had the FISA courts themselves expressed no concern at these orders that, it can be safely assumed, they were repeatedly approving (they apparently protest at the phrase “rubber-stamping”)? Why no unease from Senator Feinstein? Will the FISA courts change their behavior now that they have the word of the man who wrote the law that he never intended any such thing? Will we ever know?

Several public intellectuals and lawyers are extremely doubtful whether the current oversight arrangements can possibly work. The former Appeal Court judge Sir Stephen Sedley, writing in a recent issue of the London Review of Books, described his despair at

a statutory surveillance regime shrouded in secrecy, part of a growing constitutional model which has led some of us to wonder whether the tripartite separation of powers—legislature, judiciary, executive—conventionally derived from Locke, Montesquieu and Madison still holds good.

The security apparatus is today able in many democracies to exert a measure of power over the other limbs of the state that approaches autonomy: procuring legislation which prioritises its own interests over individual rights, dominating executive decision-making, locking its antagonists out of judicial processes and operating almost free of public scrutiny.

The arbitrary use of sweeping powers of detention, search and interrogation created by the (pre-9/11) Terrorism Act, which recently made headlines with the detention of David Miranda at Heathrow, illustrates a long-term shift both in what is constitutionally permissible and in what is constitutionally acceptable. The former may be a matter for Parliament, but the latter is still a matter for the rest of us.

I think he’s right.

This Issue

November 21, 2013

When Privacy Is Theft

The Strange Powers of Norman Mailer