In the last days of 1936, Spain was five months into a bitter civil war, in which volunteers from many countries were helping the elected government of the Spanish Republic battle a military coup led by General Francisco Franco and backed by Hitler and Mussolini. Some foreigners flocking to Spain, though, had come for another reason as well: the northeast part of the country, particularly Catalonia, was in the midst of the most far-reaching social revolution ever seen in Western Europe.

Workers had taken over factories and peasants the large estates; waiters were running restaurants and trolley drivers the transport systems. Municipal garbage trucks carried anarchist slogans. Hundreds of idealistic visitors wanted to take part in a revolution that came not, as in Stalin’s Russia, from the top down, but from the bottom up. In Barcelona, a young American economist named Charles Orr was working for the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM), or Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification—an independent leftist group with its own militia at the front.

“A little militiaman, in his blue coveralls and red scarf, trudged up the stairs to my office on the fourth floor,” remembered Orr later.

The lifts, as usual, bore the familiar sign NO FUNCIONA…

There was an Englishman, he reported to me, who spoke neither Catalan nor Spanish…. I went down to see who this Englishman was and what his business might be.

There I met him—Eric Blair—tall, lanky and tired, having just that hour arrived from London….

Exhausted, but excited, after a day and a night on the train, he had come to fight fascism…. At first, I did not take this English volunteer very seriously. Just one more foreigner come to help…apparently a political innocent.

The newcomer spoke of a book he had written, about living as a tramp in England and washing dishes in Paris restaurants. But Orr had not heard of this or of the several novels this “gawky, stammering adventurer” said he had published.

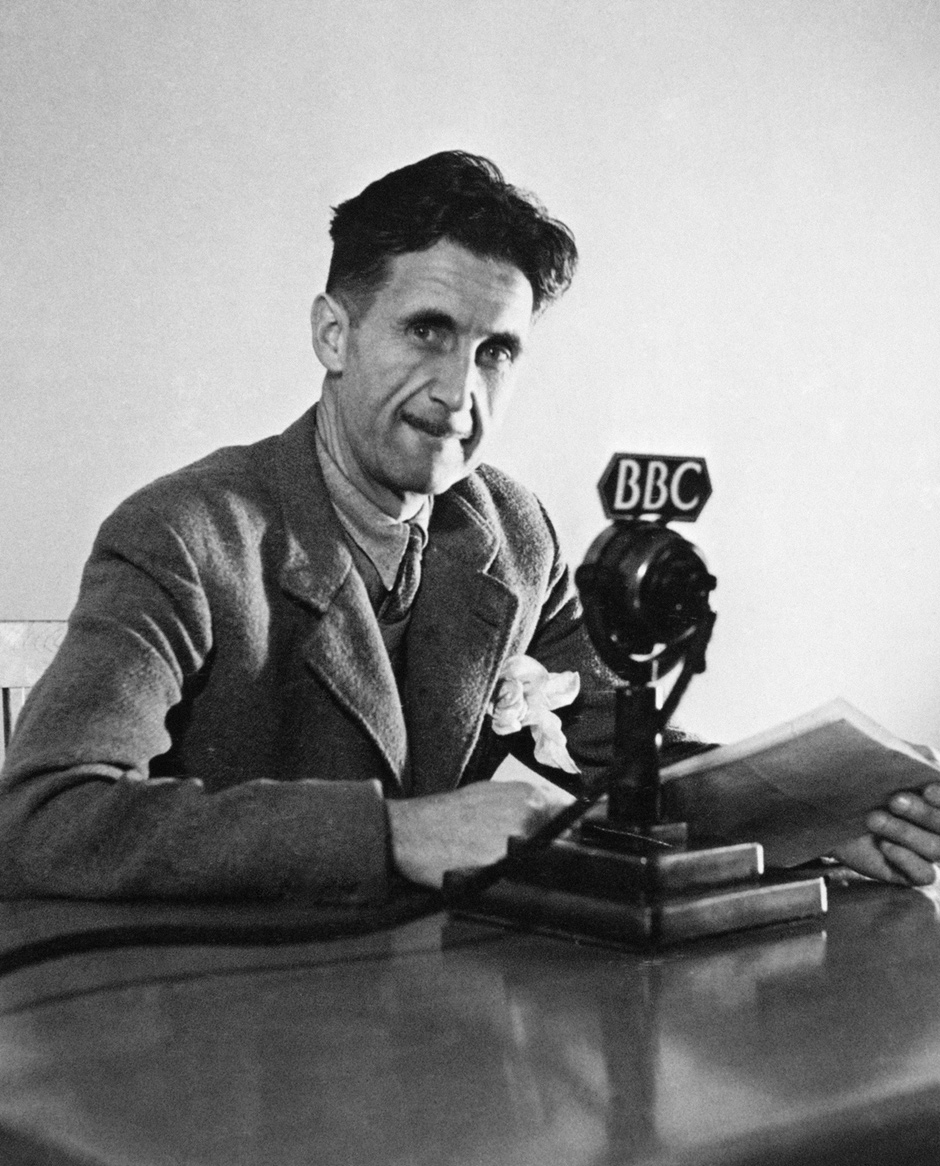

“To us he was just Eric…one of a small band of foreigners, mostly British, fighting on the Aragon Front.” This was where Blair would be sent, west of Barcelona, when he promptly joined the POUM militia. “He was tongue-tied, stammered and seemed to be afraid of people,” Orr wrote. But however inhibited he was in conversation, he was anything but that in print, where he wrote under the name of George Orwell.

Like Orr, few people anywhere had then heard of the thirty-three-year-old author, who had been supporting himself largely as a part-time bookstore clerk and by running a small grocery shop out of his home. He had finished the book that would first bring him wide notice, The Road to Wigan Pier, but it had not yet appeared.

Like a number of foreigners with whom he crossed paths in Barcelona—one was a young German named Willy Brandt—Orwell quickly found himself under the spell of the revolutionary city:

Waiters and shop-walkers looked you in the face and treated you as an equal. Servile and even ceremonial forms of speech had temporarily disappeared. Nobody said “Señor” or “Don” or even “Usted”; everyone called everyone else “Comrade” and “Thou”…. Tipping had been forbidden by law…almost my first experience was receiving a lecture from an hotel manager for trying to tip a lift-boy…. The revolutionary posters were everywhere, flaming from the walls in clean reds and blues that made the few remaining advertisements look like daubs of mud…. Practically everyone wore rough working-class clothes, or blue overalls or some variant of the militia uniform. All this was queer and moving. There was much in it that I did not understand, in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for.

Within a week, Orwell was on his way to the front. The book he would write about the following six months, Homage to Catalonia, is the one in which for the first time he fully found his voice. In 1940 he referred to it as his “best book,” and for many of us that judgment still holds, even though the novels he wrote subsequently, Animal Farm and 1984, would be more famous. This year marks Homage’s seventy-fifth anniversary, and the book merits a fresh look: at its brilliance and its flaws; at an eerie backstory that Orwell only dimly sensed; and at the odd way his explicit revisions were, for decades after his death, ignored.

In Spain, Orwell never for a moment stopped observing himself and everything around him: Who can forget his extraordinary description of exactly what it feels like to be hit by a bullet? (“The sensation of being at the centre of an explosion.”) Yet he also managed to write in the first person without ever sounding self-centered. You can open Homage at almost any page and see how he deftly amasses rich, sensory detail, but always in the service of a larger point. For example, after that sniper’s shot almost severed his carotid artery, he was put on a hospital train to the rear. As it pulled into one station, a troop train filled with Italian volunteers was pulling out for the front,

Advertisement

packed to the bursting-point with men, with field-guns lashed on the open trucks [flatcars] and more men clustering round the guns. I remember with peculiar vividness the spectacle of that train passing in the yellow evening light; window after window full of dark, smiling faces, the long tilted barrels of the guns, the scarlet scarves fluttering—all this gliding slowly past us against a turquoise-coloured sea….

The men who were well enough to stand had moved across the carriage to cheer the Italians as they went past. A crutch waved out of the window; bandaged forearms made the Red Salute. It was like an allegorical picture of war; the trainload of fresh men gliding proudly up the line, the maimed men sliding slowly down, and all the while the guns on the open trucks making one’s heart leap as guns always do, and reviving that pernicious feeling, so difficult to get rid of, that war is glorious after all.

But within the Spanish civil war was another civil war. Inside the Republic, a peculiar alliance of mainstream parties and Communists was eager to crush Catalonia’s social revolution. Some of their reasons were understandable—they feared the Western democracies would never sell arms to a Republican Spain they saw as revolutionary. But some were not. Soviet officials and Spanish Communists were working hard to gain influence, particularly over the Republic’s military and police. One major aim was to carry out a local version of Stalin’s Great Purge, in which any dissenters from the world Communist movement were branded traitors. In Spain, a principal Soviet target was the vigorously anti-Stalinist POUM.

Orwell first became fully aware of this when, in late April 1937, he returned to Barcelona on leave. Within a few days, he was unexpectedly caught up in a deadly outburst of street fighting between the Communist-dominated police on one side and the POUM and its anarchist allies on the other. Several hundred people were killed. Deeply distressed, he returned to the front line. Some weeks later, after being wounded, hospitalized, and discharged, he came back to Barcelona one last time, to meet his wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy Blair, who had come from England to work in the POUM office, and to head home with her to recuperate. It was then that he discovered that the POUM and its newspaper had been banned by the Republican government, and many of its supporters thrown in jail. He stayed out of sight for several days while he and Eileen arranged to slip out of the country before they, too, could be arrested.

She told him how, several days before, six plainclothes police had burst into her room and taken all the couple’s letters, books, and documents, including the diaries Orwell had kept during his first four months at the front. These must have been a particularly painful loss. Yet even in describing this theft of his own writing, Orwell was alert to a curious human detail:

They sounded the walls, took up the mats, examined the floor, felt the curtains, probed under the bath and the radiator, emptied every drawer and suitcase and felt every garment and held it up to the light…. In one drawer there was a number of packets of cigarette papers. They picked each packet to pieces and examined each paper separately, in case there should be messages written on them. Altogether they were on the job for nearly two hours. Yet all this time they never searched the bed. My wife was lying in bed all the while; obviously there might have been half a dozen sub-machine-guns under the mattress, not to mention a library of Trotskyist documents under the pillow. Yet the detectives made no move to touch the bed, never even looked underneath it…. The police were almost entirely under Communist control, and these men were probably Communist Party members themselves. But they were also Spaniards, and to turn a woman out of bed was a little too much for them.

During these last two brief visits to Barcelona, Orwell wrote, “You seemed to spend all your time holding whispered conversations in corners of cafés and wondering whether that person at the next table was a police spy.”1

Advertisement

Sometimes, that person was a spy, and today we can read Homage side-by-side with these agents’ reports. The USSR was the only major country willing to sell arms to the Republic, and these and the Communist-organized International Brigades helped save Madrid from Franco in 1936 and made a valuable contribution in several other battles. But Stalin’s emissaries and secret agents were doing what they could to gain Soviet control over the Republic’s forces and policies, and they often succeeded. For more than half a century, all their records were tightly locked up, but with the collapse of the Soviet Union some became accessible, and they make fascinating reading.2

Some documents, including the actual papers removed from Eileen Blair’s room, are believed to still be in closed files in Moscow. But among what we can now see is a two-page inventory of what the police took that day. This includes such items as “correspondence exchanged between Eileen and Eric BLAIR,” “correspondence of G. ORWELL (alias Eric BLAIR) concerning his book ‘The Road to Wigan Pier,’” “checkbook for the months of October and Nov 1936.” There were also letters to and from a long list of people, and “various papers with drawings and doodles.”

For some items, the English originals have disappeared and the only version on file is in German. These translations were evidently done by or for Germans involved in running Soviet espionage in Barcelona. David Crook, a British Communist agent, claims in his memoirs that during the long Spanish lunch-and-siesta, he used to slip into the office used by Eileen and the handful of other Britons and Americans with the POUM, steal documents, and quickly photograph them at a Soviet safe house occupied by “a middle-aged German couple, Gertrude and Anatol.” Gertrude and Anatol, whoever they were, presumably were reporting directly to Moscow.

Another British Communist, Walter Tapsell, was reporting to London, writing to Party superiors there that Orwell/Blair was the “most respected man in the contingent” of Britons fighting with POUM, but that “he has little political understanding.”3 And someone else may have been reporting to André Marty, the much disliked French Communist who was Moscow’s man supervising the International Brigades, for the list of materials confiscated from Eileen is in French. Another member of this cluster of agents was Hugh O’Donnell, the British Communist Party representative in Spain. The Blairs knew him, but what they almost certainly did not know was his codename, O’Brien—which, by an uncanny coincidence, Orwell was to give to the sinister villain of 1984.

In Homage, Orwell wrote, “You had all the while a hateful feeling that someone hitherto your friend might be denouncing you to the secret police.” This was even more true than he knew. David Crook, for example, posed as a POUM sympathizer, but meanwhile was reporting everything to his Soviet handlers, including his suspicions that Eileen Blair was having an extramarital affair—information potentially useful for blackmail. He would die at ninety in the year 2000, having lived his last five decades in China, his faith largely unshaken even by five years’ imprisonment during the Cultural Revolution.

Another of these shadowy figures, Frank Frankford, served in Orwell’s militia unit but, apparently as the price of escaping a prison term for having looted some paintings from a church or museum, he signed a statement accusing the POUM of fraternization with the enemy and sending “practically every night” a mule cart loaded with supplies through the front line to Franco’s troops. Orwell himself, he charged, sometimes made suspect, furtive visits to a hut near the Fascist positions. Some of these accusations appeared in the London Daily Worker. One scholar suggests that part of the fury Orwell poured into 1984 might have “been exacerbated by a bilious realization that some of the people he knew in Spain were in fact professional informers who had cultivated his friendship purely in order to shop him…perhaps in order to preserve their own skins from the rats of Room 101”4—the place of ultimate torture in 1984.

Homage to Catalonia is an unusual blend of memoir and political reportage. At the time, the international press either ignored the war-within-the-war or repeated the Communist line, which was that the POUM had been fatally infiltrated by Franco supporters. The New York Times published this canard, describing a vast conspiracy “engineered by subversive elements in the POUM” that secretly sent information about troop movements and the like to Fascist generals via radio transmissions and an invisible ink message written to Franco himself on the back of a map. Whatever the shortcomings of the POUM—and it had more than Orwell was aware of—such charges were preposterous. They rightly enraged him and were reflected later in the machinations of 1984’s Ministry of Truth.

Almost all journalists who try to elucidate a complex, violent conflict in a foreign country do so with an air of authority. Think of how someone like Thomas Friedman, for instance, jets off to Egypt or Pakistan for a few days and then tells you exactly what’s wrong and exactly what should be done about it. By contrast, one of the more subtle virtues of Homage to Catalonia is its humility. “It is difficult to be certain about anything except what you have seen with your own eyes,” Orwell writes, in one of several such cautionary notes. “Beware of my partisanship, my mistakes of fact, and the distortion inevitably caused by my having seen only one corner of events.” Homage was published in 1938, less than a year after its wounded author had left Spain, and the war was still on. But he never forgot that he had seen “only one corner of events,” and, to his credit, on some points he was not afraid to change his mind.

In Homage, for example, he blames the Republic’s military defeats on its fratricidal conflicts and the suppression by the Republican government and the Communists of the social revolution he had so admired in Barcelona. He declares that if the government “had appealed to the workers of the world in the name not of ‘democratic Spain,’ but of ‘revolutionary Spain,’ it is hard to believe that they would not have got a response”—in the form of strikes and boycotts by “tens of millions” in other countries. For Orwell, this was a rare moment of wildly wishful thinking. Most “workers of the world” had long since proven themselves not to be the revolutionary internationalists that radical intellectuals hoped for—something most notably evinced by their willingness to slaughter each other in huge numbers in World War I.

But by the time he published a long essay, “Looking Back on the Spanish War,” in 1943, he had come to the conclusion with which most historians today would agree—that “disunity on the Government side was not a main cause of defeat.” Instead, “the outcome of the Spanish War was settled in London, Paris, Rome, Berlin.” Rome and Berlin, of course, supplied Franco with a flood of troops, aviators, advisers, and state-of-the-art weapons like the latest Messerschmitt 109 fighter planes. And not just London and Paris, but Washington as well refused to sell arms to the democratically elected government of the Republic. The “thesis that the war could have been won if the revolution had not been sabotaged was probably false…. The Fascists won because they were the stronger; they had modern arms and the others hadn’t.”

Because this was a somewhat different view than the one he had taken in Homage, Orwell wanted changes in the book’s next printing. In the months before his death in 1950, he typed out corrections and marked up a copy of the book for his British publisher. Most importantly, he asked that two long chapters, comprising roughly a quarter of the text and dealing with the factions on the Republican side and claims and counterclaims about the Barcelona street fighting, be relegated to appendices—a rearrangement that did not unsay anything, but that significantly altered the book’s political emphasis.5

Most of these changes were made when the book appeared in French several years later—Orwell had also been corresponding with his French translator. But astonishingly, in his own country his wishes and the marked-up copy were ignored, and a changed edition did not appear in Britain until thirty-six years after his death. It has never appeared in the United States. If you want to read the book in English in the form that Orwell wanted it, you have to either find a library that has his twenty-volume Complete Works or order a British paperback.6 The standard American edition—whose sales by now are surely in the millions—does not reflect Orwell’s changes. He deserves better.

Norman Podhoretz claimed Orwell as an incipient neoconservative. On the other hand, more than a few of the young Americans who headed to the South as civil rights workers in the 1960s carried Homage in their backpacks or had read it. For us, Orwell was above all an example of someone willing to risk his life for what he believed in.

Particularly during the cold war, people were eager to see the book as an example, as Lionel Trilling wrote in 1952 in his introduction to the American edition, of “disillusionment with Communism”—although Orwell had few illusions to begin with. “What he learned from his experiences in Spain of course pained him very much,” Trilling continues, “and it led him to change his course of conduct.” Trilling does not say what “course of conduct” he is referring to here, and a hasty reader could take him as implying that Orwell regretted his decision to volunteer in Spain.

It is true that Orwell dropped a plan he had to transfer to the International Brigades. But concerning what mattered most he did not change his course of conduct. He had learned that people fighting for a good cause can have unsavory allies, but he remained convinced until his death that it had been worth fighting to defend the Spanish Republic. “Whatever faults the post-war Government might have,” he said in Homage, Franco’s regime was “infinitely worse.” He repeated the conviction in his essay of five years later. If the Spanish civil war “had been won, the cause of the common people everywhere would have been strengthened. It was lost, and the dividend-drawers all over the world rubbed their hands. That was the real issue; all else was froth on its surface.” And not only did he write this; he lived it. After his upsetting experience of the street fighting in Barcelona, where did he nonetheless go? He went back to the front.

This Issue

December 19, 2013

Mike

An American Romantic

Gazing at Love

-

1

Unknown to Orwell, he was also under surveillance before and after his time in Spain by his own government’s counterintelligence. One 1942 report, ironically, describes him as holding “advanced communist views.” See “Odd Clothes and Unorthodox Views—Why MI5 Spied on Orwell for a Decade,” The Guardian, September 3, 2007. ↩

-

2

Most of these records are at the Russian Center for the Preservation and Study of Recent History (RGASPI) in Moscow. Nearly two hundred reels of microfilm copies are held at the Tamiment Library at New York University, where I consulted them. Although none specifically concerns Orwell, see also the many documents reprinted in Spain Betrayed: The Soviet Union in the Spanish Civil War, edited by Ronald Radosh, Mary R. Habeck, and Grigory Sevostianov (Yale University Press, 2001). ↩

-

3

Quoted in Gordon Bowker, Inside George Orwell (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), pp. 216–217. Bowker has paid more attention to this aspect of Orwell’s life than his other biographers. I’m grateful to him for sharing some notes with me, and to Hermann Hatzfeldt for some translations from the German. ↩

-

4

Rob Stradling, “The Spies Who Loved Them: The Blairs in Barcelona, 1937,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 25, No. 5 (October 2010). ↩

-

5

Oblique testimony to this comes from a commentator for right-wing magazines who denounces the new edition as “thoroughly appalling.” See Stephen Schwartz, “Rewriting George Orwell,” The New Criterion, September 2001. Orwell only asked for these “clearly mistaken” changes, Schwartz claims, when he was too ill to quite know what he was doing. However, Orwell first described his plan for rearranging the book in a letter of July 26, 1946, three and a half years before his death. ↩

-

6

The best is Orwell in Spain (Penguin, 2001), superbly edited by Peter Davison, which contains the revised text of Homage, plus every article, review, or letter to do with Spain that Orwell wrote, and other material as well. ↩