God, it would be good to be a fake somebody rather than a real nobody.

—Mike Tyson

The afterlife of a champion boxer recalls Karl Marx’s remark about history repeating itself first as tragedy, then as farce. Even when the boxer manages to retire before he has been seriously injured, it is not unlikely that repeated blows to the head will have a long-term neurological effect, and the accumulative assaults of arduous training and hard-won fights will precipitate the natural deterioration of aging; it is certainly likely that the boxer has witnessed, or even caused, very ugly incidents in the lives of other boxers. As welterweight champion Fritzie Zivic once said, “You’re boxing, you’re not playing the piano.”

The boxer has journeyed to a netherworld of visceral, violent experience that most of us, observing from a distance, can have but the vaguest glimmer of comprehending; he has risked his life, he has injured others, as a gladiator in the service of entertaining crowds; when the auditing is done, often it is found that, after having made many millions of dollars for himself and others, the boxer is near-penniless, if not in debt to the IRS, and must declare bankruptcy (Joe Louis, Ray Robinson, Leon Spinks, Tommy Hearns, Evander Holyfield, Mike Tyson,* among others).

Ironic then, or perhaps inevitable, that the afterlife of the champion boxer so often replicates this tragic role in farcical form: recall Joe Louis, one of the greatest heavyweights in history, ending his career with two ignominious defeats at the hands of younger boxers and a brief interlude as a professional wrestler, then impersonating himself as a “greeter” in a Las Vegas casino. Arguably the greatest of heavyweight champions, unmatched in his prime for spectacular ring performances, Muhammad Ali too ended his career after a succession of humiliating and battering defeats, exploited by his manager Don King and badly in debt; in his visibly diminished state, afflicted with Parkinson’s disease, and unable to speak, Ali is frequently displayed on public occasions, often in formal attire, face impassive as a mask.

Mike Tyson, at twenty the youngest heavyweight champion in history, and in the early, vertiginous years of his career a worthy successor to Ali, Louis, and Jack Johnson, has managed to reconstitute himself after he retired from boxing in 2005 (when he abruptly quit before the seventh round of a fight with the undistinguished boxer Kevin McBride). He became a bizarre replica of the original Iron Mike, subject of a video game, cartoons, and comic books; a cocaine-fueled caricature of himself in the crude Hangover films; star of a one-man Broadway show directed by Spike Lee, titled Undisputed Truth, and the HBO film adaptation of that show; and now the author, with collaborator Larry Sloman, of the memoir Undisputed Truth.

In his late teens in the 1980s Mike Tyson was a fervently dedicated old-style boxer, more temperamentally akin to the boxers of the 1950s than to his slicker contemporaries. In his forties, Tyson looks upon himself with the absurdist humor of a Thersites for whom loathing of self and of his audience has become an affable shtick performance. He liked to come on as crazed and dangerous, screaming in self-parody at press conferences:

I’m a convicted rapist! I’m an animal! I’m the stupidest person in boxing! I gotta get outta here or I’m gonna kill somebody!… I’m on this Zoloft thing, right? But I’m on that to keep me from killing y’all…. I don’t want to be taking the Zoloft, but they are concerned about the fact that I’m a violent person, almost an animal. And they only want me to be an animal in the ring.

Once prize fights were marathons that might involve as many as one hundred rounds of three minutes each (the record is 110 rounds in 1893, over seven hours). With so much time ahead, boxers had to calculate how to use their strength, and sheer physical endurance was a high priority. The marathon fight provided time for reflection for the rapt audience, as the balance of power might shift unpredictably from one boxer to the other, in a series of oscillating actions, like a protracted play.

Fights scheduled to be marathons that ended quickly might be interpreted as mismatches, thus frauds. The most notorious heavyweight fight of the twentieth century, Jack Dempsey–Luis Ángel Firpo (1923), was also one of the shortest, ending with a victory for Dempsey in the second round after a succession of spectacular knockdowns of both fighters and Dempsey’s fall through the ring ropes onto a sportswriter’s typewriter; it is clear to us today that Dempsey should have lost the fight—he was the beneficiary of the referee’s “long count” (an extra four seconds) that allowed him to recover after he’d been pushed back into the ring by reporters.

Advertisement

Already as a young, ascendant boxer in his mid-teens Mike Tyson was drawing attention for the rapid-fire, nonstop aggression of his ring style even in amateur boxing matches in which points are scored by hits, as in fencing, without respect to the power of punches. He’d been trained—at first during weekend passes from his upstate reform school—to fight like a professional by Cus D’Amato, a revered if controversial and contentious trainer whose previous world champions were Floyd Patterson and José Torres. “The whole amateur boxing establishment hated me…. And if they didn’t like me, they despised Cus.” Typically, Tyson terrified his opponents by his very size and manner. At the Olympic trials in 1983 the Tyson legend was beginning:

On the first day, I achieved a forty-two-second KO. On the second day, I punched out the front two teeth of my opponent and left him out cold for ten minutes. Then on the third day, the reigning tournament champ withdrew from the fight.

To see Tyson’s early fights, both amateur and professional, is to see young boxers stalked, cornered, and swiftly beaten into submission by a younger boxer who pursues them across the ring with the savagery and determination of Dempsey, whose nonstop, combative, and punitive ring style Tyson imitated under D’Amato’s guidance. To see these fights in quick succession, the shared incredulity of the boxers who have found themselves in the ring with the relatively short, short-armed Tyson, their disbelief and astonishment at the sheer force of their opponent as he swarms upon them, is to witness a kind of Theater of the Absurd, which is perhaps the most helpful way to understanding boxing.

By the time he turned professional, in 1985, Tyson was modeling himself more conspicuously after Dempsey by adopting the famous boxer’s black trunks and black ring shoes worn without socks; he would enter the arena without a robe, unsmiling, truculent, and deadly-looking, to the terror of his opponents. Here was Iron Mike, D’Amato’s “antisocial” creation—“I even began to fantasize that if I actually killed someone inside the ring, it would certainly intimidate everyone.”

At nineteen, Tyson began to establish his media image as an avatar of the murderous Dempsey in an interview following his demolition of Jesse Ferguson: “I wanted to hit him on the nose one more time, so that the bone of his nose would go up into his brain.” With twelve first-round knockouts in his early career, some within seconds, no boxer has ever ascended more rapidly and more spectacularly through the heavyweight ranks than Tyson.

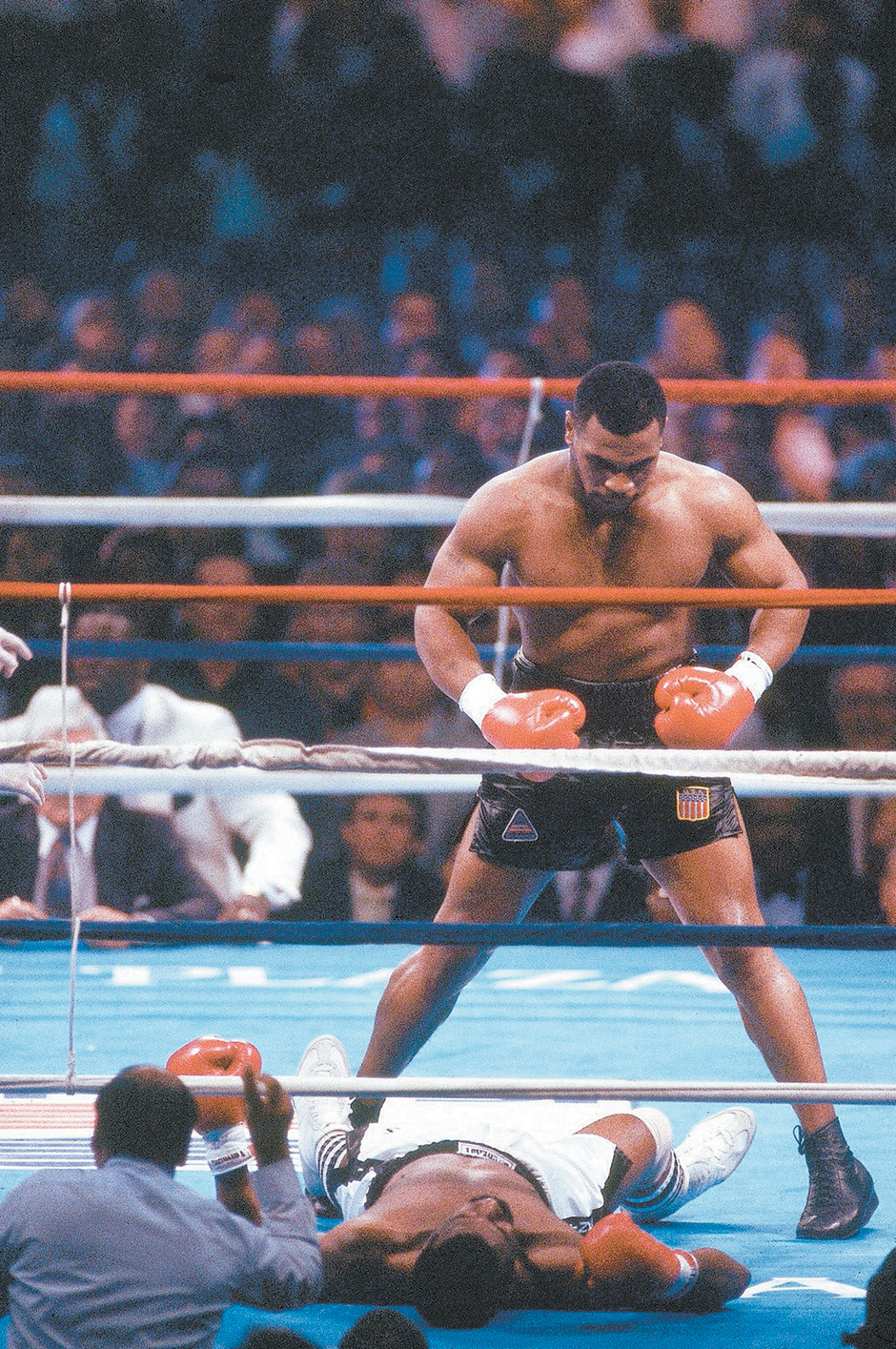

Grieving for D’Amato, who died in 1985, but determined to fulfill the trainer’s prophecy that he would become the youngest heavyweight title-holder in history, Tyson executed one of his stylish, rapid-fire dramatic victories against thirty-three-year-old title-holder Trevor Berbick on the night of November 22, 1986, at the age of twenty, before a wildly cheering crowd in Las Vegas. Stopped by the referee after two minutes and thirty-five seconds into the second round, moving swiftly to its conclusion like a malevolent ballet, the Tyson–Berbick fight is one not likely to be forgotten by anyone who has seen it; its predominant image is an older man hammered into submission by a younger man, falling hard, managing to get to his feet, and then falling hard again, helpless, onto the canvas.

Even Berbick’s trainer Angelo Dundee had to concede that “this kid” created the pressure of the fight to which his boxer could not react:

He throws combinations I never saw before. When have you seen a guy throw a right hand to the kidney, come up the middle with an uppercut, then throw a left hook. He throws punches…like a trigger.

Though Tyson had entered sports history that night, as Cus D’Amato had planned for him, he recalled:

The scariest day of my life was when I won the championship belt and Cus wasn’t there. I had all this money and I didn’t have a clue how to comport myself. And then the vultures and the leeches came out.

The strongest and most moving chapters of Undisputed Truth are those that deal with Tyson’s background. Burnished with retrospective insight, these recollections of his childhood in Brooklyn with his biological family and his boyhood in Catskill, New York, with his “white” family (Cus D’Amato and D’Amato’s longtime companion Camille Ewald, with whom he lived intermittently until D’Amato’s death) are touched with nostalgia and a bittersweet sort of regret. It isn’t surprising to learn that Tyson’s sporadic career as a criminal began when he was less than ten years old:

Advertisement

I was running with a Rutland Road crew called The Cats….… We normally didn’t deal with guns, but… these were our friends so we stole a bunch of shit: some pistols, a .357 Magnum, and a long M1 rifle with a bayonet attached from World War I. You never knew what you’d find when you broke into people’s houses.

But it will be news to many that Tyson’s criminal and drug activities continued through his teens, when he was living upstate and being trained by D’Amato.

Born in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, in 1966, Tyson would one day say that he didn’t know much about his family background. His mother, a prison matron at the Women’s House of Detention in Manhattan at the time of his birth, had been born in Virginia; for unclear reasons, possibly related to alcoholism and drugs, Lorna Mae Tyson soon lost her prison job, was evicted from her apartment, and moved to Brownsville, a rougher neighborhood: “Each time we moved, the conditions got worse—from being poor to being serious poor to being fucked-up poor.” Tyson’s mother’s friends were now mainly prostitutes and her lovers inclined to violence—though Tyson recounts how his mother once poured boiling water over one of her male friends:

That is the kind of life I grew up in. People in love cracking their heads and bleeding like dogs. They love each other but they’re stabbing each other. Holy shit, I was scared to death of my family….

Tyson had been told that his biological father, who had no part in his life, was a pimp—but also a deacon in a church.

Difficult to believe that Mike Tyson, who would weigh two hundred pounds by the age of thirteen, was once “very shy, almost effeminate shy, and I spoke with a lisp. The kids used to call me ‘Little Fairy Boy.’” At the age of seven he is introduced to petty theft by an older boy, taught to pick locks and rob houses; his first arrest for credit card theft is at the age of ten; at eleven he begins street fighting. More frequently than he is beaten on the street, he is beaten by his mother: “That was some traumatizing shit.” That Tyson’s recitation of his impoverished childhood has become somewhat rote doesn’t lessen its poignancy: “I was a little kid looking for love and acceptance and the streets were where I found it.”

Continuously in trouble with the police, Tyson is remanded to Spofford Juvenile Detention Center and treated with the psychotropic Thorazine, the first of countless medications prescribed for him through the decades. By his account he would appear to have been emotionally disturbed, prone to violence and impulsive behavior, but he feels at home in Spofford where many of his friends are also incarcerated. One day, Muhammad Ali comes to speak to the boys and makes a powerful impression on Tyson: “Right then I decided I wanted to be great.”

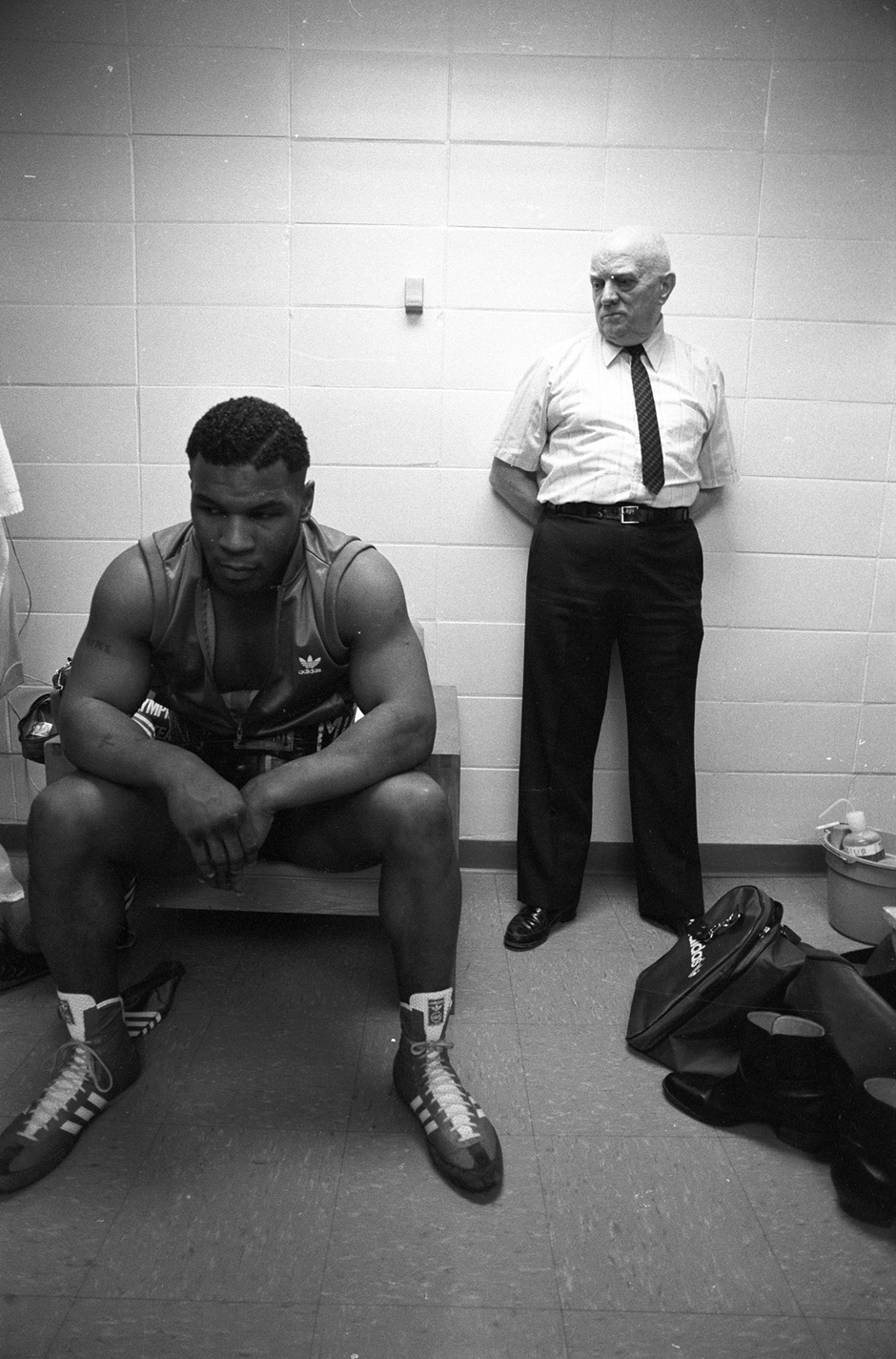

Incorrigible at age thirteen, Tyson is finally sent upstate to the Tryon School for Boys near Catskill, where in a boxing program for incarcerated boys he is introduced to Cus D’Amato. Tyson says, “I was this useless Thorazined-out nigga who was diagnosed as retarded and this old white guy gets ahold of me and gives me an ego.” It is boxing lore that after D’Amato’s first encounter with Tyson in his Catskill gym in March 1980 he called his friend and associate Jimmy Jacobs in Manhattan to tell him: “I’ve just seen the next heavyweight champion of the world.”

In this way begins the metamorphosis of a clumsy, overweight adolescent who “always thought I was shit” into one of the most disciplined and accomplished athletes of the twentieth century. Much has been written of D’Amato’s impassioned devotion to training young boxers and particularly of his training of Mike Tyson for virtually five years nonstop in his Catskill gym, a training that is as much, or more, psychological as it is physical. D’Amato teaches Tyson that the boxer is a warrior: “My job is to peel off layers and layers of damages that are inhibiting your true ability to grow and fulfill your potential.” Tyson becomes the apprentice willing to exhaust himself in the effort to obey his master:

Cus wanted the meanest fighter that God ever created, someone who scared the life out of people before they even entered the ring. He trained me to be totally ferocious, in the ring and out.

And: “We fought to hurt people; we didn’t fight just to win.”

Time not spent at the gym is spent talking avidly about boxing and watching fight films and tapes:

When I started studying the lives of the great old boxers, I saw a lot of similarity to what Cus was preaching. They were all mean motherfuckers. Dempsey, Mickey Walker, even Joe Louis was mean, even though Louis was an introvert. I trained myself to be wicked…. Deep down, I knew I had to be like that because if I failed, Cus would get rid of me and I would starve to death.

Tyson perceives that D’Amato is exacting revenge for real or imagined slights against himself by way of his ferocious young boxer, but never judges him harshly:

I was madly in love with Cus. He was the first white guy who not only didn’t judge me, but who wanted to beat the shit out of someone if they said anything disrespectful about me…. If he told me to kill someone, I would have killed them…. I was happy to be Cus’s soldier; it gave me a purpose in life.

Though the death of Cus D’Amato would be devastating to Tyson, the young boxer would continue on his succession of winning bouts for several years afterward with such opponents as James “Bonecrusher” Smith (1987)—so terrified of Tyson that he grabbed the young champion and clinched for dear life to lose each of twelve rounds in arguably the only boring fight of Tyson’s career; Pinklon Thomas (1987), knocked out in six rounds; Tony Tucker (1987); Tyrell Biggs (1987), whom Tyson said he could have knocked out in the third round of their title fight at Atlantic City but chose to knock out slowly so that he would “remember it for a long time.” In 1988 he knocked out Larry Holmes, Tony Tubbs, and Michael Spinks, the latter in ninety-one seconds, defeating the former light-heavyweight champion who had never before been knocked down.

In retrospect, Tyson–Spinks would be considered the most spectacular fight of Tyson’s career, along with Tyson–Trevor Berbick. It is possible that Tyson’s dazzling career would have begun to self-destruct eventually, given the evidence in Undisputed Truth of the young boxer’s self-destructive behavior between fights and his self-doubt as early as 1987. (“The truth is…I was sick of fighting in the ring. The stress of being the world’s champ and having to prove myself over and over just got to me. I had been doing that shit since I was thirteen.”) But with the unexpected death in 1988 of his manager Jimmy Jacobs, who had been Cus D’Amato’s longtime friend and associate and a part of his “white family,” Tyson was devastated anew, and left with no close advisers whom he could trust. “With Jim gone the vultures were circling for the fresh meat: me.”

By this time Tyson has married TV actress Robin Givens, having been told that Givens is pregnant; in one of the two worst mistakes of his young life, Tyson gives his new wife, to whom he would remain married a scant year, his power of attorney. (Shortly after their marriage Givens had a “miscarriage.”) Tyson’s other disastrous mistake is to sign contracts with the controversial boxing promoter Don King, a convicted felon who’d served time in an Ohio prison for manslaughter and whose treatment of Muhammad Ali, among other fighters, should have been known to him.

For boxing purists, Tyson’s ignominious loss of the heavyweight title in 1990 to the 42–1 underdog James “Buster” Douglas marks the end of the Tyson era. No one who has seen this fight, one of the great upsets in boxing history, is likely to forget the sight of Tyson knocked to the canvas by Douglas in the tenth round, groping desperately for his mouthpiece to fit it back into his mouth—a futile gesture. Tyson would say negligently of this fight that he hadn’t taken it seriously, had scarcely trained and was thirty pounds overweight, had been “partying” virtually nonstop (in Tokyo, where the fight took place)—but the fact would seem to be simply that the reign of Iron Mike Tyson was over.

The title Undisputed Truth is a play on the familiar boxing phrase “undisputed champion”—as in “Mike Tyson, undisputed heavyweight champion of the world,” delivered in a ring announcer’s booming voice and much heard during the late 1980s and early 1990s. A more appropriate title for this lively mixture of a memoir would be Disputed Truth. These recollections of Tyson’s tumultuous life began as a one-man Las Vegas act at the MGM casino. It is now shaped into narrative form by a professional writer best known as the collaborator of the “shock comic” Howard Stern and is aimed to shock, titillate, amuse, and entertain, since much in it is wildly surreal and unverifiable. (Like the claim that “I’m such a monster. I turned the Romanian Mafia onto coke” and that Tyson was a guest at the Billionaire Club in Sardinia, “where a bottle of champagne cost something like $100,000.”)

Mostly, Undisputed Truth is a memoir of indefatigable name-dropping and endless accounts of “partying”; there is a photograph of Tyson with Maya Angelou, who came to visit him in Indiana when he was imprisoned for rape; we learn that Tyson converted to Islam in prison (“That was my first encounter with true love and forgiveness”), but as soon as he was freed, he returns to his old, debauched life, plunging immediately into debt:

I had to have an East Coast mansion…so I went out and bought the largest house in the state of Connecticut. It was over fifty thousand square feet and had thirteen kitchens and nineteen bedrooms…. In the six years I owned it, you could count the number of times I was actually there on two hands.

This palatial property is but one of four luxurious mansions Tyson purchases in the same manic season, along with exotic wild animals (lion, white tiger cubs) and expensive automobiles—“Vipers, Spyders, Ferraris, and Lamborghinis.” We hear of Tyson’s thirtieth birthday party at his Connecticut estate with a guest list including Oprah, Donald Trump, Jay Z, and “street pimps and their hos.” In line with Tyson’s newfound Muslim faith, he stations outside the house “forty big Fruit of Islam bodyguards.”

Apart from generating income for Tyson, the principal intention of Undisputed Truth would seem to be settling scores with people whom he dislikes, notably his first wife Robin Givens and her omnipresent mother Ruth (“There was nothing they wouldn’t do for money, nothing. They would fuck a rat”) and the infamous Don King, whom Tyson sued for having defrauded him of many millions of dollars:

This other piece of shit, Don King. Don is a wretched, slimy reptilian motherfucker. He was supposed to be my black brother, but he was just a bad man…. I thought I could handle somebody like King, but he outsmarted me. I was totally out of my league with that guy.

Shown proof that he had been paid $12 million for his fight against Michael Spinks in 1988, Tyson couldn’t recall either that he’d ever been paid or “what I did with the money.” He adds, “I didn’t even have my own accountant at the time; I was just using Don’s. I didn’t have anyone to tell me how to protect myself. All my friends were dependent on me. I had the biggest loser friends in the history of loser friends.”

Nor is Tyson above using Undisputed Truth to revisit his Indiana rape trial of 1992 and to speak scathingly another time of the eighteen-year-old Miss Black America contestant Desiree Washington whom he was convicted of raping: “I told her to wear some loose clothing and I was surprised when she got into the car, she was wearing a loose bustier and her short pajama bottoms. She looked ready for action.”

To the extent that Tyson has a predominant tone in Undisputed Truth it’s that of a Vegas stand-up comic, alternately self-loathing and self-aggrandizing, sometimes funny, sometimes merely crude:

Nobody in the whole history of boxing had ever made as much money in such a short period of time as I did…. I was like some really hot, pretty bitch who everybody wanted to fuck, you know what I mean?

Defending his friend Michael Jackson against charges of pedophilia:

It was weird, everyone was saying that he was molesting kids then, but when I went there he had some little kids there who were like thug kids. These were no little punk kids, these guys would have whooped his ass if he tried any shit.

He is temporarily flush with money that he spends with the giddy abandon of a nouveau riche athlete who becomes near-bankrupt:

I was so poor that a guy who’d stolen my credit card went online to complain that I was so broke he couldn’t even pay for a dinner with my credit card.

Admirers of Tyson’s early boxing career will be surprised if not mystified to learn that even when he was undefeated as a heavyweight champion—even when he was training with Cus D’Amato as a teenager in the 1980s—he often drank heavily, like his mother, and took drugs, favoring cocaine: “I started buying and sniffing coke when I was eleven but I’d been drinking alcohol since I was a baby. I came from a long line of drunks.”

It is generally believed that Tyson’s downward spiral began at the time of the Buster Douglas debacle, but this memoir makes clear, as he admits countless times, that he’d been a “cokehead” more or less continuously. At one point his cocaine addiction is so extreme that he seems to have infected his wife Kiki, whose probation officer detects cocaine in her system, a consequence of Tyson having kissed her before she went for her drug test. “I’m talking about a jar of coke,” he writes. “I stuck my tongue down that jar and I hit pure cocaine. So much that you don’t even feel your tongue anymore.” There’s a comical account of Tyson in a fit of road rage violently attacking a driver whose car has accidentally rear-ended his own:

Someone had called the police and they pulled us over a few miles from the scene. I was as high as a kite and I started complaining about chest pains and then I told them that I was a victim of racial profiling.

After Tyson’s conviction on charges of assault he is sentenced to two years in prison in Maryland (“with one year suspended”); his most attention-getting visitor is John F. Kennedy Jr., who bizarrely assures Tyson that “the only reason you’re in here is you’re black.” Tyson encourages John Jr. to “run for political office,” an idea that, in Tyson’s account, is evidently new and startling to him. Tyson elaborates to the Kennedy heir:

No, nigga, you’ve got to do this shit…. That’s what you were born to do. People’s dreams are riding on you, man. That’s a heavy burden but you shouldn’t have had that mother and father you did.

With admirable prescience Tyson tells John Jr. that he’s “fucking crazy” to be flying his private plane. Though Tyson has been stressing his humility in prison he can’t help but brag that “shortly after John-John was there, boom, I got out of jail.”

As if in rebuke of such self- aggrandizement, every few pages there is a perfunctory sort of self-chastisement, like a tic: “I might not have been a scumbag, but I was an arrogant prick.” On the occasion of acquiring the Maori tribal tattoo that now covers nearly half his face: “I hated my face and I literally wanted to deface myself.”

The funniest jokes in Undisputed Truth trade upon racial stereotypes. Tyson speaks of being taken up by a Jewish billionaire named Jeff Greene who’d made a “billion dollars playing the real estate market” while “I was a Muslim boxer who spent almost a billion dollars on bitches and cars and legal fees.” Greene invites Tyson to dinner during Rosh Hashanah—“Shit I even got to read from the book during the Passover seder.” This is Tyson’s introduction to what he calls “Jewish jubilance.” Another joke would have drawn appreciative laughter in Vegas:

I was on another rich Jewish guy’s yacht and I watched him checking out this other Jewish guy whose boat was moored nearby. They were looking at each other, just like black people do, you know how we look at each other? And then one guy said, “Harvard seventy-nine?”

“Yes, didn’t you study macroeconomics?”

…So I’m on this boat and I see a big black guy. He’s the bodyguard for a very well-known international arms dealer. And I’m looking at him and looking at him and I just can’t place him. He came over to me.

“Spofford seventy-eight?” he asked.

“Shit, nigga, we met in lockdown,” I remembered.

One of the more lurid incidents in the afterlife of Tyson’s career is the ear-biting fracas of his fight against Evander Holyfield in 1997. Provoked by his opponent’s head-butting, which opened gashes in his forehead (and which referee Mills Lane unaccountably ruled “an accident”), Tyson lost control and bit one of Holyfield’s ears—and then, when the fight resumed, after Holyfield butted Tyson’s forehead again, Tyson bit Holyfield’s other ear. “I just wanted to kill him. Anybody watching could see that the head butts were so overt. I was furious, I was an undisciplined soldier and I lost my composure.” The referee stopped the fight, with Holyfield declared the winner. Though Tyson’s behavior was roundly condemned as poor sportsmanship, an examination of the video shows clearly that the referee behaved with unwarranted leniency toward Holyfield, and prejudice against Tyson. (Ironically, in a Golden Gloves tournament, Holyfield himself had once bitten an opponent.) About Holyfield and himself, Tyson had this to say in a recent interview at the New York Public Library:

Evander’s still fighting, he’s still trying to even the score. I’m not trying to even the score. I’m moving on to other places, which are probably dark, and places I’ve never been before, but I’m not afraid to go there, I’m not afraid to lose in life. I’m not afraid to do anything…. There’s nothing I would do unless I have a possibility of being humiliated. If I can’t be humiliated if I fail, I don’t want to do it, because only by doing that will I rise to my highest potential.

Undisputed Truth ends with Tyson in a somber, even elegiac mood, reflecting upon his Muslim faith and the “old-time fighters” like Harry Greb, Mickey Walker, Benny Leonard, John L. Sullivan. His mood here is nostalgic, remorseful—“Now I’m totally compassionate…. I’ve really come to a place of forgiveness.” But “sometimes I just fantasize about blowing somebody’s brains out so I can go to prison for the rest of my life.” Tyson writes that he has returned to A.A. and that his sobriety is a precarious matter, like his marriage. After the jocular excesses of Undisputed Truth it is hardly convincing to end on so subdued and tentative a note: “One day at a time.”

This Issue

December 19, 2013

An American Romantic

Gazing at Love

-

*

In 2003, after having earned between $300 and $400 million, Mike Tyson declared bankruptcy with $23 million in debt and $17 million owed in back taxes. ↩