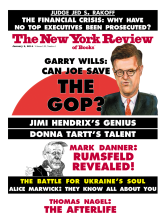

Shortly before his death at age twenty-seven on September 18, 1970, Jimi Hendrix told his friend Colette Mimram that he didn’t have much time left. He’d heard it from a fortune-teller in Morocco, and he believed her. Hendrix, who’d grown up penniless, could earn $14,000 a minute playing his white Fender Stratocaster guitar at Madison Square Garden, but he couldn’t find a minute’s peace. He was worn down by the predatory behavior of his manager Mike Jeffery, a corrupt former MI5 operative. Student radicals demanded that he play for free; the Black Panthers tried to shake him down for “support.” He had been acquitted of heroin possession in Canada but faced a paternity suit in New York. He was making a new record but had to tour constantly in order to pay for Electric Lady, the studio he was building on West 8th Street. Though famously chivalrous, he’d begun to lash out at his lovers, one of whom had to be rushed to the emergency room after he threw a bottle at her in a drunken rage. He was fed up with being a rock star: he wanted to jam in small clubs and study composition, so that he could learn to read music, maybe write for an orchestra. But Hendrix had the kind of career that doesn’t allow for sabbaticals.

In a recent documentary for the PBS series American Masters about Hendrix, I Hear My Train A Comin’, Colette Mimram says that she was shocked by the nonchalance with which he predicted his own death, but she couldn’t have been surprised. Hendrix’s lyrics depicted life as a race against time. He imagined himself “living at the bottom of a grave,” and wondered whether he would live tomorrow, or whether—as he sang in “Purple Haze,” his biggest hit—tomorrow might be “the end of time.” “The story of life,” he wrote just before he died, “is quicker than the wink of an eye.”

The afterlife, however, can go on forever if you’re a legend like Hendrix. Not only has he received belated recognition from American Masters, but he—or rather the family estate, Experience Hendrix LLC—has released a number of “new” records in the last year. (These range from the electrifying performance at the 1968 Miami Pop Festival to the desultory outtakes on the compilation People, Hell and Angels.) Hendrix is even the “author” of a new memoir, Starting at Zero, assembled from diary musings, letters, and interviews. Starting at Zero was published without the cooperation of the estate, whose involvement in I Hear My Train A Comin’ left the documentary scrubbed clean of all but the most discreet allusions to Hendrix’s prodigious appetites for women and drugs. Even so, the “memoir” is little more than a clip job, strictly for Hendrix fans, for whom every trace he left remains of talismanic significance. The Hendrix family, which finally wrested control of his estate from the lawyer Leo Branton and the producer Alan Douglas in 1995, can hardly be blamed for flooding the market with Hendrixia, even if it is of highly variable quality. Hendrix memorabilia is a big business.

And for good reason. In a very brief time, Hendrix created a body of work that does not require the purple haze of 1960s nostalgia to be appreciated. He wrote his share of girl-chasing songs (“Foxy Lady,” “Fire”); he was no stranger to the hedonism, or the flower-power mysticism, of the period. But his lyrics expressed something deeper than a desire for a life without limits, or without parents. They were a protest not so much against authority as against fate itself, in the blues tradition that he introduced—or reintroduced—to rock.

As Miles Davis wrote in his autobiography, “Jimi Hendrix came from the blues, like me.” When Eric Clapton and Pete Townshend, who had made a name for themselves copying the licks of old black bluesmen, heard Hendrix perform, they reportedly clasped each other’s hands, as if they’d seen the ghost of Robert Johnson.1 On stage, Hendrix—a left-handed guitarist who played a right-handed guitar strung for a lefty—performed with breathtaking speed and dexterity, sometimes with only one hand. Yet he never seemed like a man in a hurry. From his guitar came a ribbon of sound as radiant and pure as Charlie Parker’s alto, or Jascha Heifetz’s violin. As Townshend later recalled, the electric guitar “had always been dangerous,” but “Hendrix made [it] beautiful.” Not only was his tone ravishing, it had “mud” on it, the lived-in character that sets masters apart from their pupils.

It seemed impossible—even unjust—that Hendrix was such a young man. But this was not a revival act: Hendrix used a range of technological innovations (feedback, sustain, effects pedals) to expand the sound of the guitar, to make it “talk” in ways that it never had. His mastery of the devices that the engineer Roger Mayer would later create for him was as comprehensive as his mastery of the guitar. (The “Octavia,” a distortion-producing pedal that doubles the input signal of a guitar an octave higher or lower in pitch, is now called the Jimi Hendrix Octavia.)

Advertisement

Yet the blur, blare, and fuzz of Hendrix’s electric guitar were not ornamental; still less were they used to conceal deficiencies in his playing. They were integral to his music, adding an expressive swirl of timbres that lent his work a symphonic richness; Hendrix, a believer in synesthesia, often compared sounds to colors.2 As the classical musicologist Michael Chanan has argued in his study From Handel to Hendrix, “What he did for the electric guitar was like what Paganini did for the violin.”

No less humbling to the leaders of the British invasion was Hendrix’s rhythmic facility. Hendrix could play the lead melody and its rhythmic accompaniment at once, a skill that eluded even Clapton. He preferred to play in a trio, with only a bass guitarist and a drummer, because the services of a rhythm guitarist were hardly necessary in a one-man guitar orchestra.

Hendrix was on more intimate terms with his instrument than any guitarist in history. His only other “area of expertise,” as his friend Linda Keith observes in I Hear My Train A Comin’, was women, and they were a distant second. He was seldom without a guitar, even in bed. He played his guitar between his knees, behind his back, and upside down; he played it with his teeth, caressed its neck, and swayed with it as if it were an extension of his body. He set it on fire on stage with a butane lighter, a sacrifice of the thing he loved most. This act of creative destruction, premiered at the Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967, launched his career in the United States.

Hendrix’s flashy moves on stage—and his frilly shirts, velvet pants, and feathered hats—made him one of the most visually arresting performers of the 1960s. It didn’t hurt that he was skinny and pretty, with languid bedroom eyes and a self-effacing, irresistibly polite manner. But today one listens to Hendrix in spite of the spectacle. He had an unforgettable sound, so powerful and distinctive that it has attracted a following far beyond the world of stadium rock. His improvisations are studied by jazz musicians and sampled by hip-hop artists. Classical composers like John Adams and David Lang have paid tribute to him; the Kronos Quartet has performed a transcription of “Purple Haze.” A Frank Gehry–designed museum was built in his honor by Paul Allen, one of the founders of Microsoft, in Seattle, his hometown. “The Star Spangled Banner” hasn’t been the same since Hendrix’s gnarled yet stately instrumental at Woodstock, which seemed to evoke a nation divided. (Hendrix told Dick Cavett that he was merely playing a song he knew from school.)

Hendrix’s place in the canon is secure. But which canon? He was, of course, a brilliant rock guitarist. Yet the fact that he played rock now seems almost incidental to his achievement. In Starting at Zero, he flirts with the neologisms “Electric Church Music” and “rock-blues-funky-freaky sound.” Rock struck him as too limiting; he particularly hated the label “psychedelic rock” often attached to his work. Race was one reason. Rock was his ticket to fame in white America, but it alienated him from black R&B audiences. As Greg Tate writes in a stimulating monograph on Hendrix, Midnight Lightning (2003), “No Black male has ever been as beloved by white men as Jimi Hendrix was.”3

That love cooled black audiences on Hendrix; he was seen as too close to whites, and all too eager to pander to their fantasies about black sexuality. (Some might have nodded when Robert Christgau called Hendrix a “psychedelic Uncle Tom” after Monterey.) As Tate observes, there was “a gate at the country’s color-obsessed edge he was not able to bust wide,” the “one that reads, ‘Jimi Hendrix was different from you and me: Jimi Hendrix was for white people.’”4

The gate has opened since Hendrix’s death. His first biographer was a black New York poet, David Henderson, whose ’Scuse Me While I Kiss the Sky (1978) remains the most lyrical account of his life. And though never a major draw among black audiences, Hendrix hasn’t suffered from any lack of admiration among black musicians: Miles Davis, George Clinton, Prince, and André Benjamin of the hip-hop group Outkast are among those who have carried the Hendrix torch. (Benjamin plays Hendrix in John Ridley’s forthcoming biopic, All Is by My Side.)

Advertisement

Perhaps the most striking evolution in black perceptions of Hendrix has been in cultural criticism. Once ambivalently embraced as a great blues guitarist who made a name for himself in “white” rock, Hendrix is now celebrated as a pivotal figure in a heterodox aesthetic movement known as “Afrofuturism.” Its pioneer was Sun Ra, aka Herman Blount, a jazz pianist from Alabama who claimed to be from outer space and led a psychedelic big band called the Arkestra.

Afrofuturism—the term was coined in 1994 by the critic Mark Dery—is steeped in the tradition of the blues, yet enthralled by the promise of technology, from synthesizers to spaceships: a phantasmagorical blend of ancestor worship and science fiction. In the Afrofuturist imagination, outer space appears as an extra-terrestrial Zion, a sanctuary from the Armageddon on earth. Afrofuturism was designed to accommodate outliers like Hendrix, a performer of amplified, feedback-heavy roots music who loved Flash Gordon as a child, revered Gustav Holst’s The Planets, and often sang of life on other planets or under water.

“The idea of space travel excited me more than anything,” Hendrix says of his childhood in Starting at Zero. It’s no wonder: he grew up in a series of boardinghouses, projects, and rat-infested rooms, and had to eat at neighbors’ homes to survive. (“The night I was born,” he sings in the rippling, ominous blues “Voodoo Chile,” “I swear the moon turned a fire red.”) His father, Al Hendrix, a small, muscular man of part-Cherokee descent, was an army private who went on to cut lawns for a living. He was stationed in Alabama when, on November 27, 1942, his seventeen-year-old wife Lucille gave birth to their son in Seattle. He returned three years later from Fiji only to discover that Lucille had left the boy in the care of family friends in Berkeley. She had named him Johnny Allen Hendrix; Al suspected the boy might be named after her lover John Page. Al moved his son back to Seattle and had his name changed to James Marshall.

Al and Lucille had five more children, all of whom except Jimi wound up in foster care. It was a violent tango of a marriage, and Lucille, who enjoyed the fast life, often ran off with other men. Al drank heavily and seldom spared the rod. Lucille died of hepatitis when Jimi was fifteen, and “became an angel to him,” according to Leon, his younger brother. The celestial woman invoked in his ballad “Little Wing,” she seems to have been the only woman he ever loved. Although he was often photographed in the company of leggy blondes, his preference was for slender, light-brown-skinned women who resembled his mother.

Well before Lucille’s death, Hendrix, a quiet, brooding child, had been forced to rely on other women for emotional support. One of them was his father’s boarder, Ernestine Benson, who played Muddy Waters records for him and gave him his first guitar when he was eleven.5 It had only one string, but Hendrix made it talk. Before he learned to play a single note on his guitar, he seems to have been fascinated by the science of sound: he tied strings and rubber bands to his bed to see what sort of tonal vibrations he could produce.6 Despite his misgivings, Al bought him his first electric guitar: a right-handed guitar, since he feared his left-handed son was particularly vulnerable to evil spirits. Jimi named it after his first girlfriend and strapped it to his back, like Sterling Hayden in Johnny Guitar.

Hendrix said that if it hadn’t been for his guitar, he would have ended up in jail. The reason that he enlisted in the 101st Airborne Division—unmentioned by American Masters—was to have a two-year sentence suspended; at eighteen he was caught riding in a stolen car. He was in the army for hardly a year. In a letter from his base in Fort Campbell, Kentucky, he boasted that “if any trouble starts anywhere, we will be one of the first to go,” but he was already looking for an exit. He had formed a band with his bunkmate Billy Cox, a bassist from Virginia whose time in the army was coming to an end, and he wanted to join Cox on the road. I Hear My Train A Comin’ repeats Hendrix’s tale that he was honorably discharged after injuring his ankle on a parachute jump. But there is no record of an ankle injury in his medical files; according to his biographer Charles Cross, he pretended to be gay in order to get himself thrown out.

For the next few years, Hendrix paid his dues in black clubs, rib houses, juke joints, and pool halls—the so-called chitlin’ circuit. He played with everyone from the Isley Brothers to Little Richard. He learned to play with his teeth from the guitarist Alphonso Young, and to play behind his back from T. Bone Walker. The originality of his electric guitar playing was undeniable: Hendrix struck Cox as a cross between “Beethoven and John Lee Hooker.” But with his dandified looks and wild soloing, Hendrix was always seen as bit of a freak. Musicians on the circuit called him Marbles, because he practiced so diligently that he seemed to have lost them. Little Richard, envious of his frilly satin shirts, fired him for looking too pretty.

Arriving in Harlem in 1964, he met a beautiful young woman, Fayne Pridgeon, who recognized his talent and took him home. “He came to bed with the same grace a Mississippi pulpwood driver attacks a plate of collard greens and corn bread after ten hours in the sun,” she recalled. Outside of her bed, however, he was “painfully shy.” Harlem proved even chillier than the chitlin’ circuit. Passersby asked him if he was in the circus. “Take your hillbilly music with you,” a Harlem DJ told him when Hendrix asked him to play a Dylan record.

Hendrix felt more at home in Dylan’s neighborhood, the West Village, where he moved in the summer of 1965. Leading a band called Jimmy James and the Blue Flames, he became known as “Dylan Black” for his Dylanesque Afro. Hendrix, who thought he had a terrible voice, admired Dylan’s “nerve to sing so out of key” nearly as much as his songwriting. (Hendrix would later earn Dylan’s praise for his spellbinding cover of “All Along the Watchtower.”) One of his early admirers in the Village was Linda Keith, Keith Richards’s girlfriend. She took Chas Chandler, the bassist in the Animals, to hear him. Chandler wanted to produce records, and believed that with the right singer he could turn the murder ballad “Hey Joe,” narrated by a cuckold on the run after killing his wife, into a hit. When he walked into Cafe Wha? in August 1966, “Jimmy James” was strumming “Hey Joe.” A month later, Chandler flew Hendrix to London.

Swinging London was as close to outer space as a black science-fiction fan could get in 1966, outside of Vietnam. It felt like “a kind of fairyland” to Hendrix. Chandler set him up in Ringo Starr’s old flat. (“He needed to be looked after,” according to Keith.) Within a month of his arrival, he had a fetching new girlfriend, the super-groupie Kathy Etchingham; a band, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, with Noel Redding on bass guitar and Mitch Mitchell on drums; and a record deal. Before he even stepped into the studio in January 1967 to record his extraordinary debut, Are You Experienced, he was an underground legend in London. England’s embrace had its less savory side. The tabloids called him “the wild man of Borneo”; Germaine Greer lamented that British audiences “wanted him to give head to his guitar and rub his cock over it.” But Hendrix was too sly—and too pumped up from this jolt of recognition—to reject the part of super-stud. He was making some very influential admirers. Clapton thought he sounded like “Buddy Guy on acid”; Paul McCartney, dazzled by the speed and virtuosity of his playing, called him “Fingers Hendrix.”

It was McCartney who recommended Hendrix to the concert promoter Lou Adler, who was organizing the Monterey International Pop Festival. Adler had never heard of him—Are You Experienced hadn’t yet been released in the States—but he took McCartney’s suggestion. It was a baptism by fire. At the end of the Experience’s forty-minute set, Hendrix smashed his flaming guitar and scattered burnt offerings from the stage. The crowd was transfixed. Pete Townsend, who had gone on before Hendrix with the Who and smashed his guitar, felt cruelly upstaged; his act, he pouted, had been a “serious art-school concept with a clear manifesto.” But Hendrix gave the audience something it wanted far more than any “art-school concept.” His impact on the counterculture was so profound that the FBI opened up a file on him. But as Starting at Zero makes plain, Hendrix remained a 101st Airborne vet in his politics, distrustful of Black Power and antiwar protest. Even his psychedelic costume at Monterey, he confessed to a friend as he went on stage, was “only for show.”

When Are You Experienced appeared in American record stores a month after Monterey, word of mouth had already laid the groundwork for Hendrix’s conquest of the New World. Six months later came the follow-up, Axis: Bold as Love, which had some of his strongest ballad writing. Then, in April 1968, Hendrix disappeared into a studio near Times Square to make his four-side masterpiece Electric Ladyland. In search of a bigger sound—and increasingly estranged from his bass guitarist Noel Redding—he invited other musicians into the studio: drummers, saxophonists, organists. The songs grew longer and more ambitious, at times almost orchestral.

Working with a twelve-track recorder for the first time, Hendrix and his engineer, Eddie Kramer, inserted a range of otherworldly sound effects. Hendrix made dozens of takes of each song; no detail was too small for his attention. Exasperated by Hendrix’s perfectionism, Chandler resigned, followed by Redding. When his group the Jimi Hendrix Experience released Electric Ladyland in October 1968, the band no longer existed. But it was the first record Hendrix produced himself, a defiantly unclassifiable work of blues futurism, and the fullest expression of an imagination that refused to be confined by the three-minute pop single.

Electric Ladyland was the last recording he completed in the studio. When he died, he was working on the follow-up, posthumously released as First Rays of the New Rising Sun. He was at the height of his creative powers but felt strangely powerless. He’d developed ulcers from touring too much—on his first American tour, he played forty-nine cities in fifty-one days—and increasingly depended on cocaine and amphetamines. They were supplied by the bisexual super-groupie Devon Wilson, a former prostitute, part-time girlfriend, and full-time heroin addict who lived with him on West 12th Street. (He called her “Dolly Dagger” for betraying him with his arch-rival Mick Jagger.) Chandler’s departure left him at the mercy of Mike Jeffery, who was determined to reunite the Experience. Jeffery was particularly unhappy when Hendrix replaced Redding with his old bunkmate Billy Cox, and surrounded himself with black musicians: he was afraid whites would be scared off.

The last album Hendrix released in his lifetime was a live date with his only all-black group, the Band of Gypsys, with Cox and the drummer Buddy Miles. Recorded at the Fillmore East on New Years Eve, 1970, Band of Gypsys was the funkiest album Hendrix ever made, a bold return to his roots. Miles Davis, with whom he had been jamming, was in the audience that night.7 The music he heard would soon be echoed in his own Hendrixian electric jazz. Davis was particularly impressed by “Machine Gun,” a slowly unfolding, apocalyptic blues in which Hendrix used feedback to simulate the sounds of gunfire, helicopters, and bombs.

Narrated by a man forced to kill someone who is in turn forced to kill him—“even though we’re only families apart”—it immerses the listener in a furious combat zone, a place where Hendrix might have landed had he not been discharged from the army. The fear and paranoia could not have been hard for him to imagine. Everyone seemed to want a piece of him: a cut of his profits, a place in his bed, a share of his drugs. At the Isle of Wight Festival in August 1970, he told Richie Havens, “They are killing me.”

Less than a month later, he went to London to recuperate in the arms of an old lover, a German heiress and ice skater named Monika Dannemann. Unable to fall sleep because of the amphetamines he was using, he took nine tablets of her Vesparax, eighteen times the recommended dose for a man his size, and went to bed. Dannemann found him unconscious the next morning and called an ambulance. The post-mortem examination concluded that he choked on his own vomit on the way to the hospital. He was buried in Seattle near his “little wing,” his beloved mother Lucille, who was only a few years older when she died.

-

1

As the jazz pianist Brad Mehldau has written in a perceptive essay comparing Hendrix to Beethoven and Coltrane, his sound has always provoked a mixture of awe and terror, what the Romantics called “the sublime.” See Mehldau, “Coltrane, Jimi Hendrix, Beethoven and God,” BradMehldau.com, May 2010. ↩

-

2

Electric Ladyland (Continuum, 2004), a monograph by the British guitarist John Perry, is an especially sharp primer on Hendrix’s musical innovations. ↩

-

3

Though fame and wealth seemed to transport him to a post-racial planet, there were sometimes bitter reminders of how black people lived on earth. On a visit to Seattle in 1968, he and his family were refused service at a restaurant until an eight-year-old girl asked for his autograph. ↩

-

4

Black soldiers in Vietnam, who knew that Hendrix had been in the 101st Airborne Division and saw him as one of their own, were a major exception to this rule, according to Michael Herr in Dispatches. ↩

-

5

As deferential to the estate in the details as in the broader outlines, I Hear My Train A Comin’ repeats the myth that Al Hendrix bought his son’s first guitar. In fact, Al Hendrix considered playing music “the devil’s business.” ↩

-

6

Scholars of contemporary classical music now see Hendrix as an “American maverick” in the tradition of Harry Partsch and John Cage, who created the prepared piano in Seattle a year before Hendrix’s birth. ↩

-

7

Davis and Hendrix discussed making a record together, but the project collapsed when Davis insisted on being paid $50,000 up front. Davis later divorced his young wife, the singer Betty Mabry, after discovering that she’d been sleeping with Hendrix. His admiration and fondness for Hendrix, however, were undiminished. ↩