The current Thing to Say about Republicans is that they are caught in a civil war—the Tea Party against the Establishment, “wacko birds” against “the adults,” fringe against mainstream. One of the most clamorous bearers of this message, on his TV show and in various other media, is Joe Scarborough. He has denounced Republicans for putting up outré candidates (like Todd Akin, Richard Mourdock, Christine O’Donnell, and Sharron Angle) to indulge their resentments, not to win elections. He has, in turn, been called a RINO (Republican in Name Only) by the objects of his criticism. He protests that he is the true Republican, principled and pragmatic like the heroes of his new book.

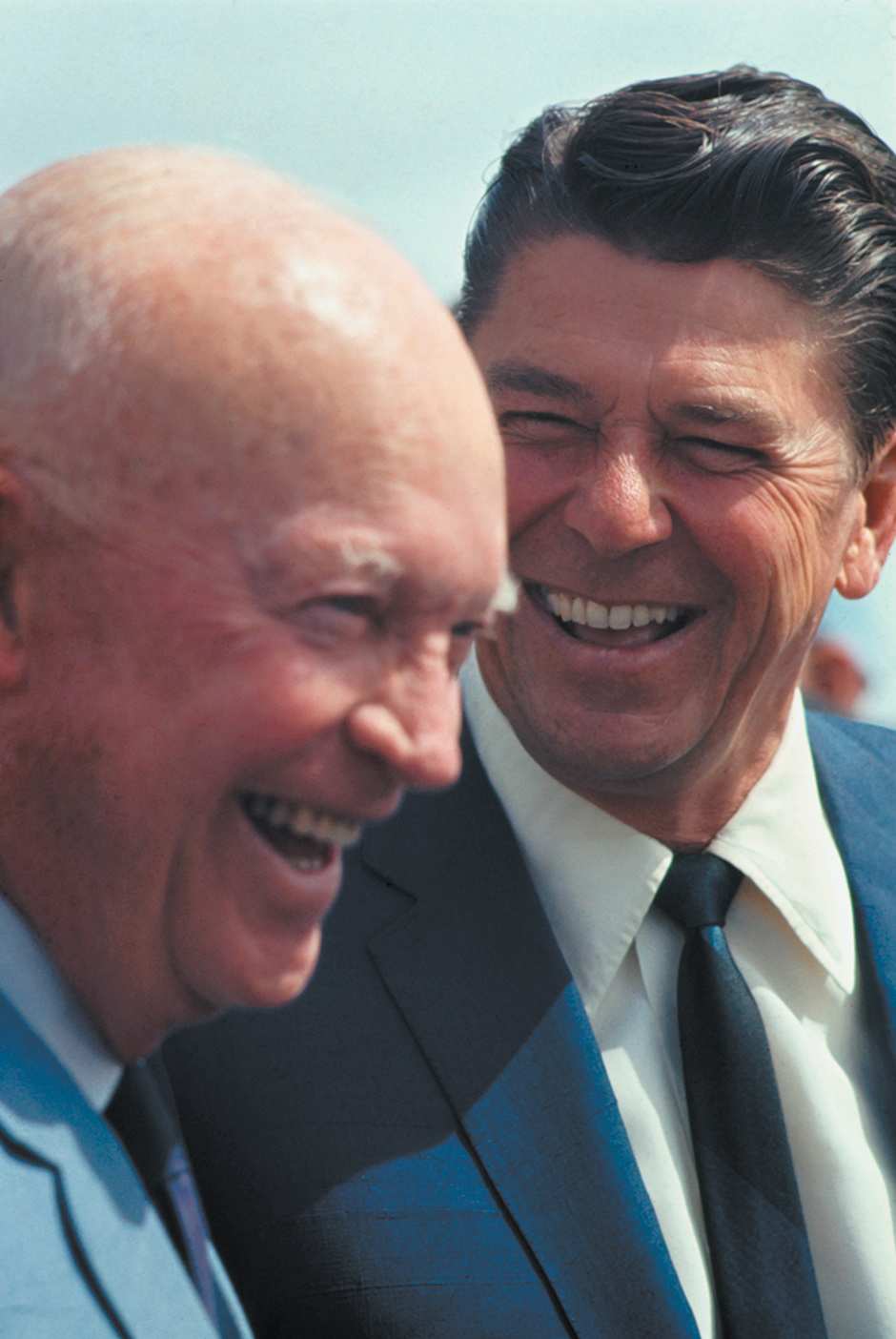

There have, by his estimate, been two miracles of Republican moderation—Dwight Eisenhower and Ronald Reagan. They set the standard nationally, though Scarborough, forced to look for some model on a more modest scale, can find one in “the one brief shining moment” that was Camelot-on-Pensacola-Bay, his own three and a half terms as representative from Florida’s First District:

By carrying a 95 percent conservative rating while making strategic alliances with Democratic allies, I boxed out the competition. I also assured myself a place in Congress for the rest of my life if that had been my goal. Because I focused around the clock on building broad coalitions that would also do the nation good…. I constantly studied the political realities around me and asked what I could do to reach out to those who would not naturally support me. If there were something I could do that would help my constituents, be good for the district, and be consistent with my conservative beliefs, I focused like a laser on getting the job done. And I always tried to remain pragmatic, able to adapt to changing conditions.

This book, then, tells the Republicans how to cure their troubles. Simply go and be Ike and Ron—and Joe.

To drive home this recommendation, the author gives us his theory of everything that has happened in American politics since 1945. (He dates all recent history, for reasons to be gone into, from “the sellout at Yalta.”) For Scarborough, the systole and diastole that give our political life its pulse are alternating extremism and pragmatism. This beat is the same for both parties. When Democrats become extreme—as when George McGovern (by Scarborough’s telling) championed “acid, amnesty, and abortion”—Republicans win. When Republicans put up an extremist like Barry Goldwater, Democrats win. Through it all, the good sense of the public is vindicated—it prefers the middle to either extreme. Scarborough puts the law in an interesting way:

Whether it was Hillarycare or Obamacare, the government shutdown or the Iraq War, politicians in both parties have fed the worst instincts of their most extreme party factions and then paid for it at the voting booth.

This seems evenhanded until one notes the specifics. Clinton launched Hillarycare in his first term and still won a second term. Obama passed Obamacare in his first term and still won a second. Bush launched the Iraq War in his first term and won a second. Is that paying at the voting booth? Scarborough is not looking to history, but to his own current itches—his opposition to Obamacare and to Ted Cruz’s shutdown of the government (not Gingrich’s) as part of his current agenda for Republicans.

Over and over, a closer look shows how skewed is this reading of political history. The moderate is supposed to be pragmatic, to adopt what works; but over and over we see that Republican moderates would fail without their extremists. George H.W. Bush needed Lee Atwater’s dirty tactics to get him into office, and he lost when he reverted to moderation by raising taxes (which Reagan also did). Bush defeated at first the forces raised against him by Pat Buchanan’s “pitchforkers” in 1992—but in what worked over time, Buchanan was the pragmatic victor:

[Buchanan] revolutionized the modern Republican Party by providing the blueprint to a GOP congressional majority. Buchanan’s conservative populism was especially persuasive in districts like my own where Republicans rarely won congressional races. It was persuasive because so many of his policy positions were outside a Washington Republican mainstream that all too often capitulated to big business and big government even when it was not the conservative thing to do.

That sounds like the Tea Party our author has come to rein in. And no wonder. Scarborough admits that he won his congressional seat as an enthusiastic member of the Gingrich Revolution in 1994. He was in favor of the first government shutdown before he was against the second one:

The coming Republican Revolution of 1994 mixed Buchanan populism with mainstream GOP orthodoxy. Newt Gingrich put together a winning political strategy that kept Republicans in the speaker’s chair in the US House of Representatives for sixteen of the past twenty years.

But Scarborough became a moderate in time for his brief period in office, and thus could be a shining Camelot figure of the Ike-Ron sort. He deserted “Gingrich, the long-term visionary,” for a more pragmatic colleague in the House, Steve Largent of Oklahoma. That kind of conversion does not disqualify Scarborough as a model, since even his favorite conservative philosopher, Bill Buckley, was against Scarborough’s first great ideal, Eisenhower, before he was for his second one, Reagan (and even Reagan had been a New Deal Democrat).

Advertisement

Scarborough’s pretense that he believes in an evenhanded oscillation of fringe and center in both parties continually breaks down. We are given two great icons of moderation on the Republican side, but not a single one on the Democratic side. When Lyndon Johnson wins, it is not because of his own moderation but because the Republicans went extreme with Goldwater. Bill Clinton won because the first President Bush wobbled between his own heartfelt goals and those of Atwater, and Clinton was reelected because Dick Morris helped him play against Gingrich’s grandiosity.

There cannot be a Democratic equivalent of the Republican “icons” Ike and Ron in Scarborough’s scheme. Some might want to put Franklin Roosevelt in that position, but Scarborough knows that he was just the man who set Democrats on a radical course at Yalta, and gave Republicans an enduring anti-extremism position:

For conservatives [not extremists, you notice, but Scarborough’s own true conservatives], Yalta now brought together two irresistible forces: contempt for Roosevelt and the growing fear of Communism’s spread. Both were potent in and of themselves. Mixed together in the story of the sellout at Yalta they fed on one another.

After five years of standing shoulder to shoulder with a Democratic president leading the fight against Adolf Hitler, Republicans suddenly had a case to make against FDR on foreign policy that was equal in weight to the domestic case….

Roosevelt was now not only the embodiment of socialism at home. He was, because of Yalta, an abettor of Communism abroad. It may have been an oversimplification of actual events, but most powerful political arguments usually are. The linkage of an expansive government at home with a weak foreign policy abroad gave the right an internally coherent political philosophy that would grow steadily in the postwar years and eventually lead to landslide victories for both Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. Liberalism’s failures at Yalta, in China, and in the nuclear arms race’s infancy gave Buckley and his apostles the kick-start that “movement conservatism” needed. America’s political system would never be the same.

Scarborough revives the old canard that Roosevelt (and Churchill) “sold out” Eastern Europe to Stalin at the meeting of Allied leaders while World War II was still being fiercely waged. But as historian James MacGregor Burns demonstrated, “Roosevelt didn’t give Stalin Eastern Europe; Stalin had taken Eastern Europe.” At that point, we had nothing we could give away.

By resurrecting the Yalta myth, Scarborough concludes that there cannot be moderate Democrats, since radicalism is built into the party’s DNA. No matter what its candidates do, they are the party of New Deal socialism and Yalta. When he says that Democrats have suffered from extremism, going “hard left,” he means that they have been even more outrageous than their party’s normal extremism—whether in the “acid, amnesty, and abortion” purportedly championed by McGovern, or in becoming even more socialist than the New Deal with Hillarycare and Obamacare.

His simplistic radical–pragmatic tick-tock of power ignores a great variety of different factors—the World War II halo around Eisenhower, the impact of JFK’s assassination on the 1964 election, the effect of September 11 on Bush’s second-term victory, to name only a few. And longer-term structural factors are filtered out entirely. Consider just three—race, religion, and money.

Race. Scarborough was born in the South one year before the explosive summer of 1964, which saw the passage of the Civil Rights Act, after the longest filibuster in Senate history against it by three defenders of the segregated South (Senators Robert Byrd, Richard Russell, and Strom Thurmond); the murder of the civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner in Philadelphia, Mississippi; Barry Goldwater’s successful plea to Senator Thurmond to become an outspoken Republican; the Goldwater nominating convention, at which southern delegates renamed their convention hotel “Fort Sumter”; Goldwater’s loss of all states outside his home Arizona and five that had been part of the Democrats’ “Solid South.”

Helped by the analysis of Kevin Phillips, Nixon four years later built his Southern Strategy on those five states, after his own wooing of Strom Thurmond. It made him president, and left a template Ronald Reagan adhered to, launching his 1980 campaign at the fairgrounds outside Philadelphia, Mississippi, the murder site of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, criticizing the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and opposing a memorial day for Dr. King. As president, he tried to protect tax exemption for segregated colleges and vetoed a civil rights bill.

Advertisement

According to Scarborough’s book, none of these things happened. He says the Southern Strategy is a “laughable” liberal myth. Nixon was elected not because he built on Goldwater’s southern success but because he was a noble moderate until his private demons led him into the Watergate cover-up. Up till then, Scarborough says, in the combined votes of the Nixon and Wallace tickets “conservatism in the classic sense carried the day in 1968.”

Really? The support for Nixon-Agnew and Wallace-Lemay was a triumph of moderation? Scarborough, born into a Thurmondized South, literally cannot see race in any part of his home region’s history. Certainly not in its current efforts to exclude black and Latino voters by registration laws, identity tests, and narrowed windows for voting. These are purportedly aimed at “voter fraud,” which does not exist to any significant extent. Every other explanation is admissible, but not race in the historically innocent Land of Thurmond.

Racism is not confined to the South, of course—and neither are Republican efforts to limit black and Latino voting. But the reflexive political use of race is usually found among Republicans—as in the newsletters of Ron Paul, where Holocaust deniers and Confederacy restorers found a welcome. When Rand Paul was not plagiarizing others, his books and speeches were being ghostwritten by a self-styled “Southern Avenger.” Republicans do not see racism in their ranks because it has for so long been denied as to become invisible to its practitioners.

Religion. One of the original selling points for the Tea Party was that it had moved on from the obsessions of the religious right. It was about deficits, jobs, and small government, not about abortion, gay marriage, prayer in schools, and creationism. But as soon as Republicans gained a majority in state legislatures, there was a flood of anti-abortion laws proposed or passed, with religious rationales or backing. Since abortion is legal, those who want to outlaw it just try to make it impossible to get, on fake grounds of “women’s health” (as they exclude blacks under cover of “voter fraud”).

On similarly fake grounds, Republicans use the Catholic bishops’ opposition to contraception as an excuse based on “religious freedom” to oppose the Affordable Care Act. The bishops’ case is phony—no one is forced to use or not use contraception by the act. But bishops say that countenancing the act offends the bishops who follow Rome in condemning it (not actual Catholics who overwhelmingly exercise their right of conscience in using contraceptives).

The defense of victimized Catholic bishops reached a comic peak when Jeb Bush (one of Scarborough’s moderate Republicans) speculated that Obama closed our Vatican embassy (he didn’t) as “retribution for Catholic organizations opposing Obamacare.” The religious right is alive and well in all kinds of Republicans—in global warming deniers, whose attitude toward climate science resembles their denial of evolution; in voter restrictions to exclude “un-Americans”; in those who oppose gay marriage, the rights of Muslims and atheists, or the need for sex education in the schools.

Money. One bit of Scarborough’s wishful thinking is that Republicans will be saved by Wall Street correcting Main Street. The rational money managers will rein in the extremists of the Tea Party. But the Tea Party’s eruption in the town hall meetings of 2009 was funded by the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity. The right-wing laws passed by Republican state legislatures follow a plan drawn up by the millionaires-funded American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). Corporate money, spouting from the Citizens United decision of the Supreme Court, has flowed into elections for local judges, state legislatures, and “citizens’” opposition to government. There is every reason for the rich to promote measures that limit the vote, promote a defiance of science, or stigmatize “aliens.”

This is not cynical opportunism on their part. They believe what Romney told them in their plush hideaway—that 47 percent of Americans are moochers who earn nothing, pay nothing, and deserve nothing. By that logic, the moochers should be kept from voting, or from getting anything the earners have acquired. Their attitude is perfectly summed up by Republican Bruce Rauner, a multimillionaire now running for Illinois governor, who issued this statement:

I’ve worked extremely hard and feel incredibly blessed to have earned financial success…. Capitalism is the greatest poverty-fighting machine in the history of mankind…. I can’t be bought or intimidated by the special interests.

The astonishing thing is that much of the public agrees with that “too rich to be bribed” creed. The proof that we live in a plutocracy is not that the wealthy get most of the prizes in our society, but that majorities think that is how it should be. Even to criticize what the super-wealthy get is to wage “class war.” That is why Democrats must shy from words as toxic as “redistribution.” Rebecca Blank, a former acting secretary of commerce, could not be nominated to the Council of Economic Advisers because she voiced the truism that “a commitment to economic justice necessarily implies a commitment to the redistribution of economic resources.” A new foundation set up to study unequal income found that the gap between the super-rich and everyone else has grown, but that support for the belief that “government should reduce income differences between the rich and poor” has gone down even as the gap widened. So the supposedly “Third Way” think tank warns Democrats that any populist talk of raising taxes on the rich will doom them. Wealth is untouchable, is sacred, for reasons the pope just diagnosed:

While the earnings of a minority are growing exponentially, so too is the gap separating the majority from the prosperity enjoyed by those happy few. This imbalance is the result of ideologies which defend the absolute autonomy of the marketplace and financial speculation…. In this system, which tends to devour everything which stands in the way of increased profits, whatever is fragile, like the environment, is defenseless before the interests of a deified market, which becomes the only rule.

The opposition to any tax raise on the rich explains why America has the greatest disparity of income between the top few and the rest of society. That disparity is actually greater in four other countries (United Kingdom, Greece, Poland, Ireland) when income is measured before taxes. It is only after taxes that America surges to the lead among all nations. Does it matter that America leads in this disparity? Jill Lepore suggests one way that it does, when she discusses our deadlocked Congress:

Polarization in Congress maps onto one measure better than any other: economic inequality. The smaller the gap between rich and poor, the more moderate our politicians; the greater the gap, the greater the disagreement between liberals and conservatives. The greater the disagreement between liberals and conservatives, the less Congress is able to get done; the less Congress gets done, the greater the gap between rich and poor.

Actually, income disparity accords with many other things, as the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has found. The greater the income gap, the higher the teenage pregnancy rate (poverty, ignorance, lack of sex education, and opposition to contraceptives are all at play here). The greater the income gap, the more education suffers, the less there is of social mobility, the greater the difficulty of reaching higher education, and the higher the premium put on it.

How can big money be the cure for our politics when it is the cause of most of its problems? Scarborough, along with every second pundit in Washington, claims that Republicans will get a national majority when they trim back their extremist positions. Others say that demographic trends among blacks and Latinos, women and young people make it dangerous for them to court majorities. Andrew Hacker, in these pages, shows that the power of the Republicans, in the House, the state legislatures, and the courts, comes from their ability to thwart majorities.* A majority of votes cast for members of the House in 2012 went to Democrats, but—thanks to gerrymandering after an off-year election with low turnout and fierce Republican focus—the Republicans won by a disparity mimicking the income gap. In Pennsylvania, for instance, Republicans won only 47 percent of the votes but walked away with 72 percent of the seats.

The House still has the power that Scarborough credits Gingrich with gaining for them in 1994. But the situation is more like the reverse of the one Scarborough thinks he is describing. In fact, the things he opposes—the New Deal, Obamacare, “Yalta”—are the mainstream, and Republicans only have the obstructive power their extremists give them. Republican power is minority power, seen in their record-breaking resort to filibusters to block majority votes in the Senate, and in their plans to stock the Senate with majority-thwarters by rescinding the Seventeenth Amendment: they want to take away the people’s power to elect senators and give the power to appoint them back to state legislators, who are already limiting voting times and qualifications.

On issue after issue—reasonable gun control, women’s rights to contraceptives or elective abortion, marriage equality, easier voter access—a majority of Americans disagree with Republicans, who cannot admit this without losing their fanatical core. They claim they have no war on women, but they cannot change positions on abortion without losing their religious base. They cannot admit any gun restrictions without bringing down the wrath of the NRA. They cannot loosen immigration laws without infuriating the nativists among them. They cannot loosen their voting restrictions or votes on welfare without alienating their Confederate avengers. Yet in all of this they are protected by their untouchable backers, the rich who can never, never, ever pay more taxes. Scarborough’s silly picture of American politics leaves out most of the things that matter—including (but not restricted to) race, religion, and money. And the greatest of these is money.

-

*

See “2014: Another Democratic Debacle?,” in this issue. ↩