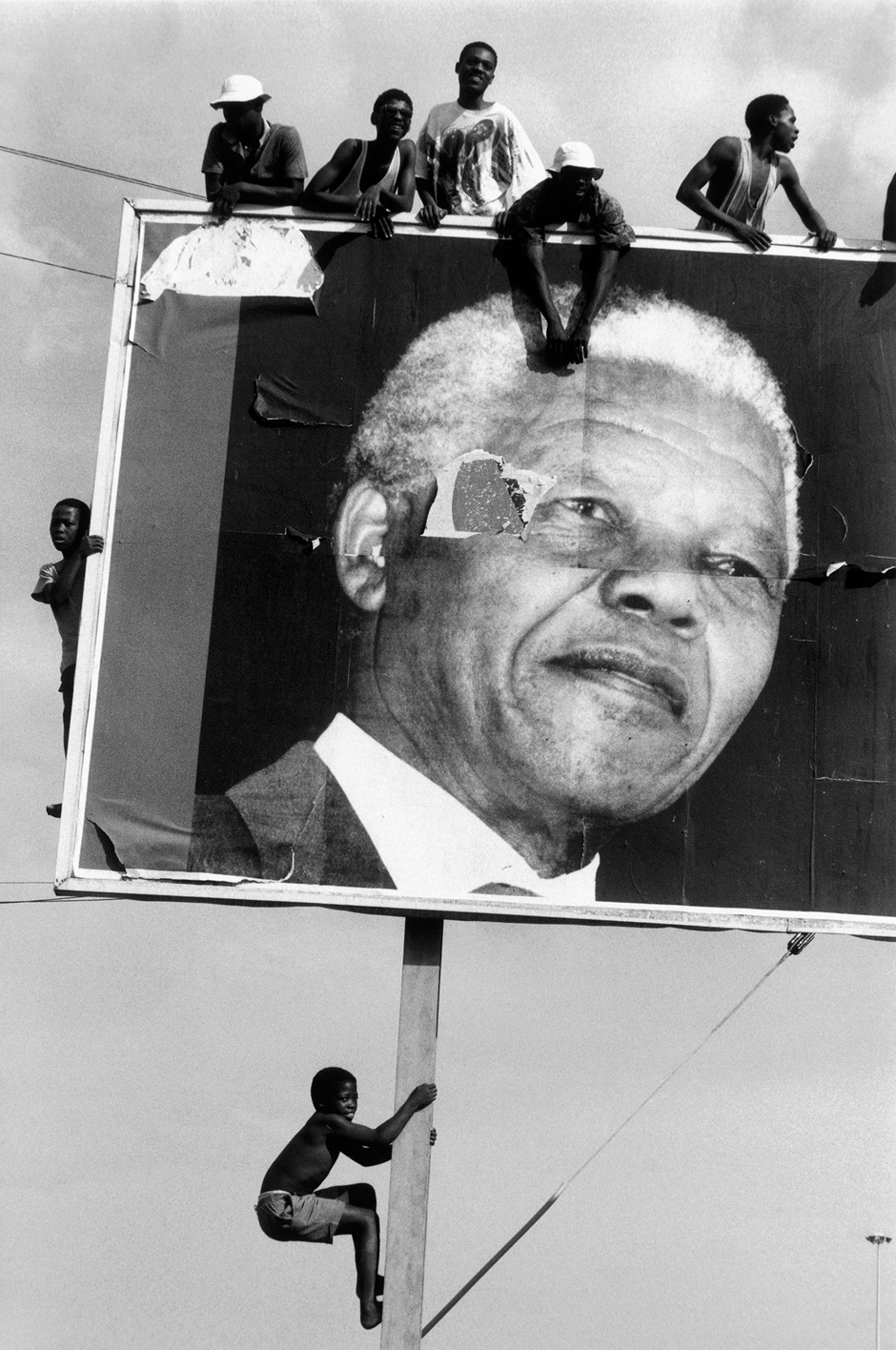

Nelson Mandela has died after a long life—long yet lamentably truncated in that he spent twenty-seven of the best years of his manhood incarcerated at the pleasure of the state.

Incarcerated, he was hardly powerless. During the final years of that long sentence he in effect exercised a power of veto over the foreign policy of his country, exerting more and more of a stranglehold over his jailers.

With F.W. de Klerk, a man of much smaller moral stature, yet also, in his way, a contributor to the liberation of South Africa, Mandela held a turbulent country together during the dangerous years between 1990 and 1994, exercising his great personal charm to persuade whites that they had a place in the new democratic republic while step by step emasculating the separatist white right wing.

By the time he became president in his own right, he was already an old man. His failure to throw himself more energetically into the urgent business of the day—the creation of a just economic order—was understandable if unfortunate. Like the rest of the leadership of the ANC, he was blindsided by the collapse of socialism worldwide; the party had no philosophical resistance to put up against a new, predatory economic rationalism.

Mandela’s personal and political authority had its basis in his principled defense of armed resistance to apartheid and in the harsh punishment he suffered for that resistance. It was given further backbone by his aristocratic mien, which was not without a gracious common touch, and his old-fashioned education, which held before him Victorian ideals of personal integrity and devotion to public service.

He managed relations with a wife whose behavior became increasingly scandalous with exemplary forbearance.

He was, and by the time of his death was universally held to be, a great man; he may well be the last of the great men, as the concept of greatness retires into the historical shadows.

—This statement first appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald.