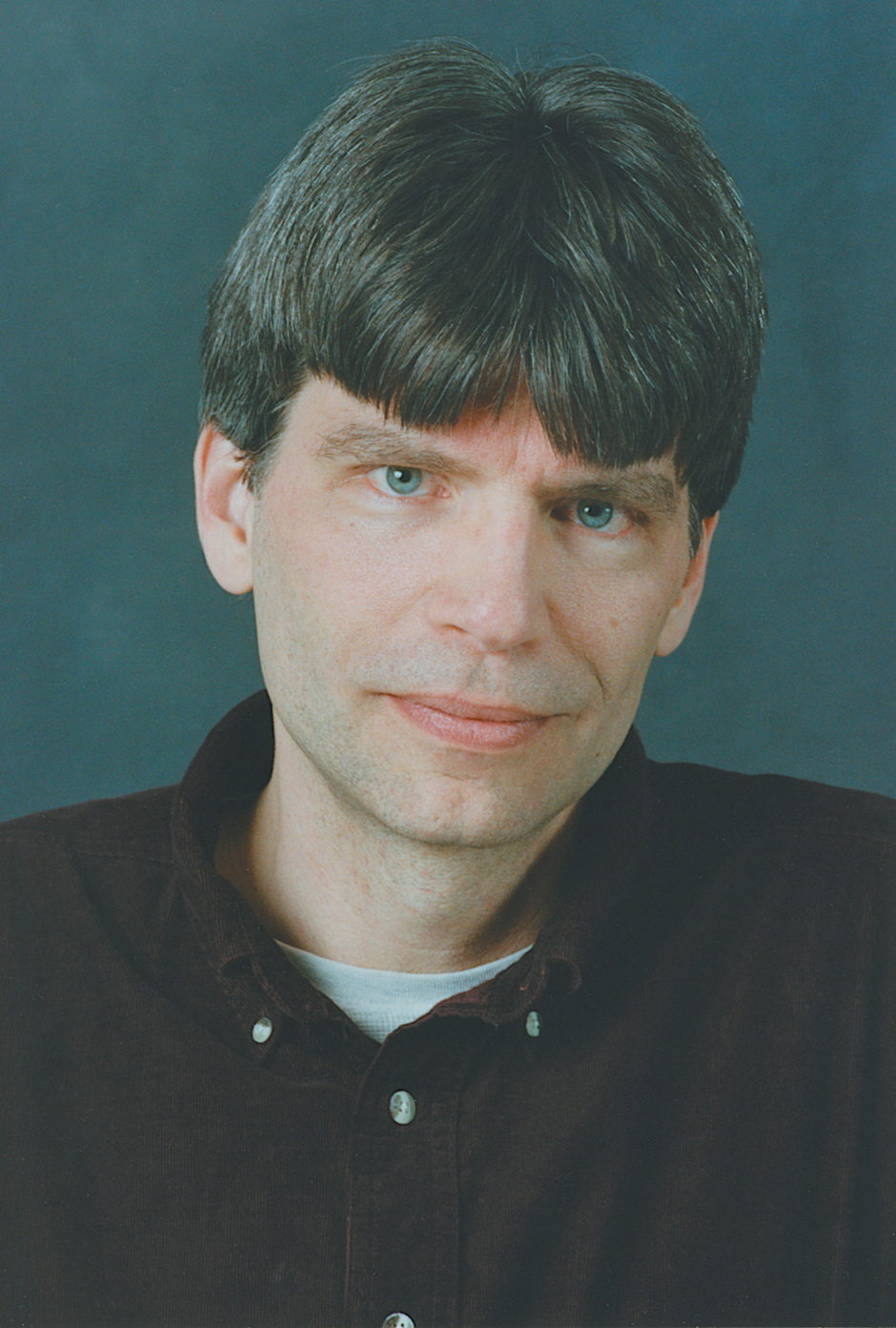

Richard Powers has equal claim to being the most forward-looking American novelist and the most old-fashioned. What is old-fashioned is his unabashed desire to write novels that are, in their essence, philosophical. His novels tend to possess the qualities we expect from the best literature—vivid characters, engrossing stories, and surprising, at times glorious prose—but Powers’s greatest interest often seems to lie in asking, if not always answering, the most vexing questions about history, science, race, art, time, wisdom, and joy.

In this he resembles Jan O’Deigh, the librarian narrator of his 1991 novel The Gold Bug Variations: “From birth, I was addicted to questions. When the delivering nurse slapped my rump, instead of howling, I blinked inquisitively. As a child I pushed the ‘why’ cycle to break point.” As a novelist Powers pushes the why cycle—and often his readers—to the breaking point, a propensity that recalls the kind of unapologetically intellectual novel that hasn’t been fashionable since Saul Bellow’s prime. Powers’s curiosity about technology, business, and medicine recalls the even more distant, realist novelists of the late nineteenth century, who took it upon themselves to educate readers about recent developments in agriculture or politics or fashion.

Yet many of the futuristic subjects that fascinate Powers—cognitive neuroscience, genetic engineering, computer science—are well beyond the grasp of most contemporary novelists. These are difficult disciplines to write about in laymen’s terms, let alone dramatize in a novel. Powers, in other words, makes things very tough on himself. Part of the fun of reading him is to see how he wriggles out of his own snares. But a greater thrill is to join with him in untangling the most urgent and confounding puzzles of our age.

The first puzzle posed by Powers’s imaginative, intellectually demanding, and sometimes maddening new novel is its title. Orfeo is a peculiar name for the story of a composer, Peter Els, who appears to be an anti-Orpheus. Els’s music, far from charming every living thing, tends to repel. He creates what The New York Times (in the novel) describes as “audience-hostile avant-garde creations”: a twelve-hour chamber ballet oratorio based on the life of the nineteenth-century transhumanist philosopher Nikolai Fyodorovich Fyodorov called Immortality for Beginners; a string quartet dictated by probability functions and Markov chains; a chanson of impossible difficulty, the words provided by Ezra Pound’s “An Immortality,” written “for a voice that could reach any note”; a piece with no fixed tonality written for piano, clarinet, theremin, and soprano, set to Kafka’s “The Great Wall of China,” which “consists of regions of mutating rhythmic fragments dominated by fixed intervals, constantly cycled and transposed.” His masterpiece, and only major produced work, is The Fowler’s Snare, an opera about the 1534 siege of Münster. “That was the kind of music Els wrote,” writes Powers, “more people onstage than in the audience.” Els’s compositions are less excruciating to read about than one imagines them to sound, but perhaps not by much.

Orfeo begins in “the tenth year of the altered world,” or 2011, when Els is seventy. This makes him a few years younger than the so-called minimalists La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass, and six years older than John Adams. Els admires all of these composers—the novel even includes an extended appreciation of Reich’s Proverb. As a character he seems modeled after them, at least in part. Like them, Els becomes a “Minimalist, with maximal yearnings,” who layers “ecstatic melodies over driving syncopations.” But professionally he is a minimalist in a different sense: in his entire life he has finished only a handful of pieces, and when the novel begins, he hasn’t written a note in eighteen years.

He has, however, discovered a new form of composition. After retiring from a teaching job at a small liberal arts college, he has become fascinated by the nascent field of biocomposing, a field so cutting edge that it doesn’t quite exist in our own reality, at least not yet. A biocomposer turns nature into music:

People now made music from everything. Fugues from fractals. A prelude extracted from the digits of pi. Sonatas written by the solar wind, by voting records, by the life and death of ice shelves as seen from space. So it made perfect sense that an entire school, with its society, journal, and annual conferences, had sprung up around biocomposing. Brain waves, skin conductivity, and heartbeats: anything could generate surprise melodies. String quartets were performing the sequences of amino acids in horse hemoglobin.

If you like twelve-hour chamber ballet oratorios about nineteenth-century transhumanist philosophers, you will love horse hemoglobin string quartets. But Els decides to go further. “The real art,” he proposes, “would be to reverse the process.” He wants to implant living organisms with musical scores, to turn “a living thing into a jukebox.” He hopes to engineer an organism—specifically the common bacterium Serratia marcescens—so that its DNA can be read like a musical score. What kind of music will this score notate? It’s immaterial, he decides. The medium matters to Els more than the message. Bacteria will outlast digital files, paper, and human memory. His inscribed Serratia will carry his music, whatever it may be, closer to immortality than any other music in existence.*

Advertisement

Els, who studied chemistry in his youth, assembles an amateur lab in his Pennsylvania home. Online he finds that he can purchase all the machines he needs for less than $5,000, auctioned off by biotech start-ups that have gone bust—items like a cell incubator, a low-temperature freezer, a thermal cycler. He makes a centrifuge from a salad spinner, and uses a rice cooker to distill water. From other websites, including one called Mr. Gene, he buys made-to-order strands of DNA, five thousand base pairs long. He splices this DNA into bacterial plasmids, trying to figure out how to engineer genetic code. Els marvels that, in the year in which he was born, nobody knew what genes were made of. Now he’s designing them. “Do-it-yourself bio: the latest mushrooming cottage industry.”

Els is making progress with his new pastime when Powers sets into motion a series of events even less likely than a solar wind sonata. Els’s crisis begins when Fidelio, his fourteen-year-old golden retriever and sole companion, suffers a stroke. Instead of calling a friend or a veterinarian, Els dials 911. The dog expires, but a few minutes later, two officers arrive at Els’s door. Why, they wonder, had Els called the police about his dog? “It felt like an emergency,” says Els, satisfying neither the officers nor us. (Loyal readers of Powers will know better than to expect an airtight plot.) Els has left the door to his study open, and the snooping officers notice beakers, tubing, jars with printed labels, a small refrigerator, a compound microscope, a computer, and other high-tech equipment. When they ask what he’s storing in all the petri dishes, Els tells them that it’s bacteria. This is not the right answer.

A couple of days later, two agents from the Joint Security Task Force arrive at Els’s doorstep. Els obediently explains that he’s manipulating the DNA of a toxic microorganism. He then stands by, lodging barely an objection, while the agents dismantle his equipment and carry it off, along with his bacterial cultures. Els tells himself that the federal agents will soon realize their error and return his equipment. It briefly occurs to him to call a lawyer but he decides against it. (Further inexplicability: “He’d never engaged a lawyer for anything, not even his divorce. Calling one now felt criminal.” A surprising statement coming from a man who doesn’t hesitate to call the police over a sick dog.)

The next morning, returning from his daily walk—in his car, conveniently, having driven to a park one mile away in order to walk a three-mile loop—he sees that his house has been cordoned by yellow crime-scene tape. Men in white helmets and hazmat suits are removing additional equipment from his home, and even exhuming his golden retriever from the lawn. Breaking from character—obedient no longer—Els keeps driving. That afternoon he flees town. Meanwhile, in an unfortunate coincidence, the CDC reports a Serratia marcescens outbreak at Alabama hospitals. Nine people are dead. Els is suspected. On the radio he hears himself being called the Biohacker Bach. A national manhunt is ordered. Els still declines to call a lawyer, nor does he prepare a statement in his defense. Instead he takes off on a road trip.

The novel proceeds in two alternating narratives. The first follows Els on the lam, as he embarks, “in a Zen trance,” on a nostalgic and largely capricious journey across the country and through his past. After hiding out briefly at a friend’s cabin in the Alleghenies, he drives to Champaign-Urbana, where he attended graduate school and met his wife, whom he later divorced; to his wife’s house, in the St. Louis suburbs; to Phoenix, where an old collaborator is running a clinical trial for an experimental Alzheimer’s drug; and finally to California to visit his adult daughter, whom he calls “my only decent composition.”

Els’s escape makes up only about one third of the novel. The longer, intervening sections tell the story of his life, beginning with an early memory of listening to music as an eight-year-old and ending in what appears, on the novel’s ambiguous final page, to be his death. Powers handles the structure artfully; Els never encounters a character from his past before we have met that character in one of the flashback sections. The chapters are separated not by numerical headings but by abstract confessional statements that approach the mysticism of koans:

Advertisement

Maybe I made a mistake. But Cage says: A “mistake” is beside the point. Once anything happens, it authentically is.

Life is nothing but mutual infection. And every infecting message changes the message it infects.

The best music says: you’re immortal. But immortal means today, maybe tomorrow. A year from now, with crazy luck.

Close readers may observe that none of the interludes is longer than 140 characters. As it turns out, they are tweets written by Els on the final leg of his journey. A work of high-concept performance art, it is fated to be his one lasting artistic creation.

What emerges from this tripartite braiding of the narrative is a comprehensive portrait of Els that is often more convincing for its many contradictions. He is an artist who has spurned his creative impulses; a composer whose single-minded dedication ruins his marriage and his relationship with his daughter, even as he admits to himself that he values his family more than his art; an introvert who, when thrust into the national spotlight, basks in his celebrity; a moralist so disturbed by similarities between his opera The Fowler’s Snare and the siege on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, which occurs weeks before the opera’s debut, that he tries to cancel the performance, yet when he comes under suspicion for terrorism, he accepts the allegations. “I did what they say I tried to do,” he tweets. “Guilty as charged.”

Els’s theories about the nature of music are no less conflicted. Powers, for all his erudition, is rarely pedagogical. Where other novelists might create dramatic tension between characters, he builds tension through a consideration of opposing ideas. He is less interested in reaching resolutions than in exploring the jumble of contradictions he develops. So music assumes for Els an ephemeral quality that is “beyond taste, built into the evolved brain”; and yet, as much as Els would like to believe “that music was the way out of all politics,” he concludes that “it’s only another way in.” “All I ever wanted was to make one slight noise that might delight you all,” he thinks, while extolling the glories of making music for nobody at all: “That’s as good as it gets…. Without an audience: so long as no one listens, you’re better than safe. You’re free.”

Elsewhere he finds in music “an inner logic, dark and beautiful,” and declares that music “doesn’t mean things. It is things.” And most gnomic of all: “music forecasts the past, recalls the future.” This statement only begins to make sense as a description of Orfeo itself, a novel in which the story of our hero’s present-day journey forecasts the story of his past.

None of Els’s many ruminations about music match, for elegance, the conclusion reached by Joseph Strom in The Time of Our Singing, another of Powers’s musically themed novels: “The use of music is to remind us how short a time we have a body.” Els instead is caught between two of the most common motivations for making art: the joy of creation (“What was music, ever, except pure play?”) and a desire for immortality (as the titles of his compositions suggest). But his efforts come to naught. What joy he finds in creating music withers after the trauma of The Fowler’s Snare, as does any chance at recognition, let alone immortal renown.

As Els grows older, he loses his passion for music altogether. In his sixty-sixth year, he awakes one morning with the realization that his hearing has changed: “Something had broken in the way he heard.” An ear doctor, with the Pynchonian name of Dr. L’Heureux (“Dr. Joy”), orders a brain scan. It reveals a series of small lesions that have managed to deaden Els’s musical facility. Dr. Joy’s diagnosis: music will never again bring Els joy.

Els returns to science, his first love. Noodling with bespoke DNA in his jury-rigged lab, he rediscovers the joy of creation. Powers here introduces an idea that he has earlier proposed in Generosity (2009), and also The Gold Bug Variations, in which the geneticist Stuart Ressler, undergoing the reverse of Peter Els’s transformation, discovers late in life a passion for music. Powers suggests that biotechnology has advanced to the point where it has become an art form in itself. And a sophisticated one at that. In its elegance and powers of invention, it is poised to rival, if not surpass, such traditional forms as literature and music. Genetic engineering is our era’s “real creative venture,” “the greatest achievement of [our] age, the art form of the free-for-all future”:

Billions of complex chemical factories in a thimble: the thought gave him the cold chill that music once did. The lab made him feel that he wasn’t yet dead, that it wasn’t too late to learn what life was really about.

As Powers splices Els’s joint passions, the metaphors begin to mix:

To Els, music and chemistry were each other’s long-lost twins: mixtures and modulations, spectral harmonies and harmonic spectroscopy. The structures of long polymers reminded him of intricate Webern variations. The outlandish probability fields of atomic orbitals—barbells, donuts, spheres—felt like the units of an avant-garde notation. The formulas of physical chemistry struck him as intricate and divine compositions.

These are among the most electric passages of writing in the novel. But they beg the question: Are we really to believe Els? As with so many of his musical endeavors, he fails to complete his grand project. A skeptical reader might wonder whether his musical bacteria project is not just another brilliant concept that he has failed to bring to fruition. For that matter, might not all of Els’s philosophizing be seen as the flailings of a failed artist who would rather abandon his work than risk falling short of perfection? If so, Orfeo might be taken as a portrait of self-delusion—a cautionary tale about the dangers facing any artist whose preoccupation with intellectual considerations prevents him from giving himself fully to the joys of “pure play.”

Els’s ambition becomes increasingly austere, and increasingly unsettling, as Orfeo progresses. Near the novel’s conclusion he is asked what kind of composition he had dreamed of writing. “I wanted awe,” says Els. “A sense of the infinite.” He is more specific in a tweet: “I wanted a piece that would say what this place would sound like long after we’re gone.” What will our planet sound like after human beings go extinct? It may sound like wind, rain, or the crashing of waves. But mostly it will sound like silence. As Els’s collaborator puts it, “What’s more beautiful than music you can’t hear?” (To which beleaguered readers might respond: music that you can hear.)

Yet once again Els is contradicting himself. Less than fifty pages earlier, Powers writes: “He’d never wanted anything but to…make something worth hearing, and to send it out into the world.” Twenty pages earlier he writes that Els’s goal is to “make his great song of the Earth…music for forever and for no one.” Which Els are we supposed to credit—the one who wants to make music for everybody, or for nobody? Or are we to conclude that the two are, somehow, the same thing? Carried beyond a certain point, complexity slips into incoherence. Readers can decide for themselves which view of artistic creation they endorse, but in the meantime the character of Peter Els, vacillating between two profoundly different views of artistic creation, begins to disintegrate.

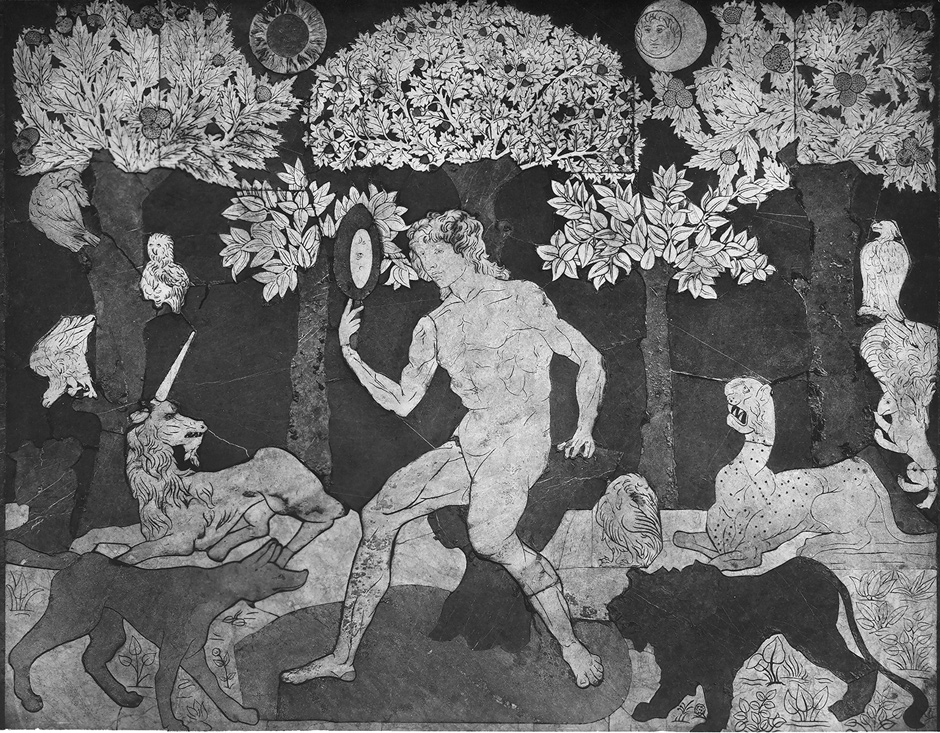

Even grimmer than Els’s vision of a perfect, inaudible composition is his conception of artistic immortality. When the subject of immortal works of art arises, we tend to think of examples like the Lascaux cave paintings, Leonardo da Vinci, the works of Shakespeare, even Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607), the oldest opera still performed today (and a possible inspiration for Powers’s title)—works that survive, and bring joy, centuries or even millennia after their creation. But that is a limited view. What will be the fate of The Divine Comedy and Beethoven’s symphonies after man is expunged from the universe?

Powers follows this line of thinking to its ominous conclusion. At the end of Els’s journey he tweets, mendaciously, that his project has been a success. He claims that he has let loose his bio-engineered Serratia, that his “song” is spreading into the atmosphere, taking refuge in the grout between bathroom tiles and circulating in the air we breathe, silently inhabiting us all. “I left the piece for dead,” he tweets, “like the rest of us. Or for an alien race to find, a billion years after we go extinct.”

Pause to imagine that alien archaeologist a billion years from now as it examines, with its X-ray vision or hypersensitive tentacles or electromagnetic pulses, the DNA of Serratia marcescens, and discovers in the bacteria’s genes a musical composition—a composition that scores the sound of silence. Will our alien archaeologist experience delight? Admiration? Empathy? Will he be charmed like the animals and trees that were moved by Orpheus to leap into the air and dance to his songs? And what difference will it make to us?

I prefer Joseph Strom’s view, no matter how simplistic it might seem by comparison: “The use of music is to remind us how short a time we have a body.” Let the word “music” be replaced with “sculpture” or “dance” or “literature” or even “biotechnology.” Art, it’s true, may only provide false comforts. But false comforts aren’t so bad. Jason and the Argonauts had Orpheus accompany them so that his songs could drown out the call of the Sirens. False comforts have their uses. In fact they are all we’ve got.

-

*

A precursor to Els’s project is a 2003 experiment performed by Pak Chung Wong at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Washington. Wong encoded snippets of the Disney song “It’s a Small World (After All)” in artificial DNA sequences, which he implanted into the bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Earlier this year, the Canadian poet Christian Bök, after spending eleven years teaching himself biochemistry and genetic engineering, succeeded in injecting bacteria with a DNA sequence that corresponds to a poetic couplet (“Any style of life/is prim”). Els has no awareness of these projects, but Powers must. ↩