Wordsworth famously defined poetry as “emotion recollected in tranquility.” An obituary, prepared ahead of someone’s death, has been called emotion anticipated in tranquility. In reading the well-prepared obituaries about Ariel Sharon, one gets the impression that the eight years he’d spent in a vegetative state removed the sting from the strong emotions that he aroused in his lifetime. His death, unlike his stormy life, was accepted, if not in complete tranquility, then at least with resignation.

According to Nahum Barnea, Sharon’s sons, Omri and Gilad, affectionately called their father “the Caucasian.” They didn’t mean a white man. What they alluded to was the fact that although Sharon’s parents, Vera and Shmuel, were both born in what is now Belarus, they met and married in the Caucasus. But they meant even more than that. The word “Caucasian” may evoke a strongly built agrarian tribal chieftain—a man fiercely loyal to his family and his people, while ferociously mean and vindictive toward his enemies, namely, the rest of the world.

Indeed, Sharon was loyal to his friends. I once heard from Yael Dayan, the daughter of Moshe Dayan (himself an example of a man reputed to have no friends), that when her husband Dov was severely debilitated from Parkinson’s, only Sharon, his old friend, kept ringing him week in and week out. As for Sharon’s vindictiveness, a case in point is Israel’s Operation Defensive Shield, in 2002, in which Sharon cornered Yasser Arafat within the confines of his compound in Ramallah and personally went to great lengths to make the Palestinian leader’s life as miserable as possible. His only constraint was a promise he had made to the Americans not to kill Arafat. An acquaintance of mine who knew about Sharon’s obsession muttered under his breath that this was what gave revenge a bad name.

Sharon was born in 1928 in Kfar Malal, a cooperative village about ten miles north of Tel Aviv. Back then, each family in the village was allotted a plot of land of equal size. But as Uzi Benziman, Sharon’s unauthorized biographer, tells us, Sharon’s family was the only one in the village that demarcated its property with fences and protected it with dogs. Every once in a while the family enlarged its plot so that soon it became the biggest in the village. In this account, the family relied on its dogs, but had no friends.

This anecdote carries with it a sense of territoriality, like old lions that urinate to mark their domain. Later, of course, Sharon was in charge of Israel’s occupied territories. Then, too, the feeling was that he was not some messianic ideologue of the Greater Israel, but a man possessed with something far more basic: raw animal territorialism.

By all accounts, Sharon had an astoundingly quick mind. But he was either untrained for, or simply distrusted, any form of abstract thinking. Once, when he was prime minister, he heard a highly theoretical presentation given by a high commander of the military’s Southern Command. At the end of the presentation, I was told, he asked the general, “But where in all of this is the killing of Arabs?” He meant two things. First, “Cut the bullshit; be concrete.” But his remark also expressed his general attitude toward Arabs: he hated them when they were strong, and he despised them when they were weak. Sharon didn’t have a trace of the kind of nativist romanticism that Dayan or Yigal Allon had. His attitude toward Arabs was brutal at its core.

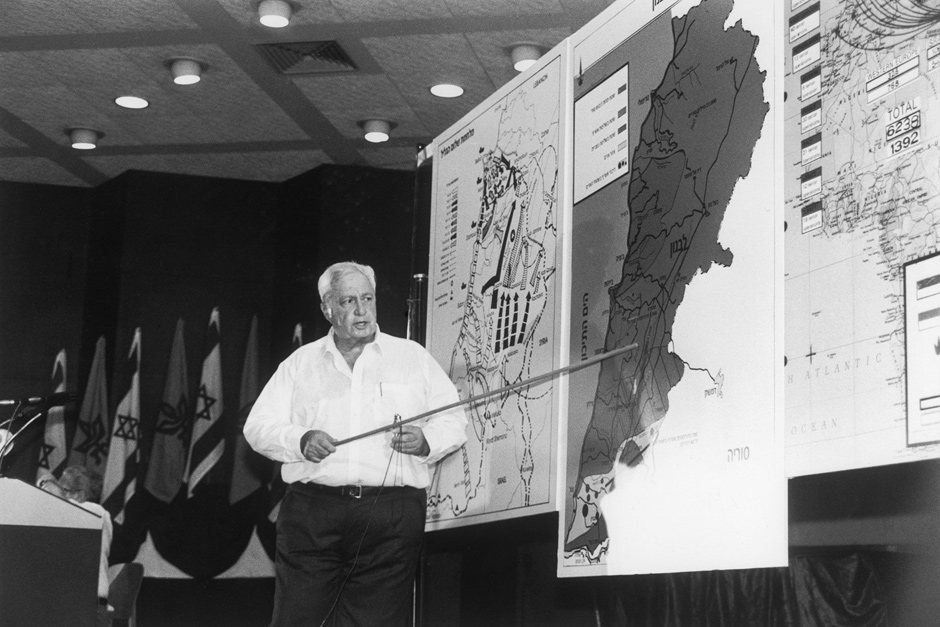

Sharon’s abhorrence of abstract thinking included distaste for law and morality, and ended in a total mistrust of ideology. Any ideology. He was a pre-ideological general who fought in ideological wars. This gave him the aura of a medieval warlord, or a Roman political general, of the kind that populates Plutarch’s Parallel Lives. Part of Sharon’s dark charm, of which he had plenty, was the feeling that in him you could encounter primordial elements—unmediated and uncluttered by ideological superstructures. Among these elements were military glory, gluttony, and, in his later years as a politician, a Nietzschean will to power. As prime minister, his ambition was to do a great historical deed in order to shape the future map of Israel. He wanted to be worthy of David Ben-Gurion’s stature; other Israeli politicians he held in contempt.

I first met Sharon when I was still in high school. It was during a long-distance walking race that lasted a few days. He stopped by, perhaps to view his future soldiers. His profile was reminiscent of a young emperor on a Roman coin. Much later he became heavy both physically and in his authoritative manner. But he struck me then as amazingly handsome, although already on the chubby side—better built, perhaps, for bullying than for long-distance walking. I don’t remember what his rank was. Probably lieutenant colonel. But I do remember that even with that modest rank, he had already made an indelible mark on Israeli life. How did he do so?

Advertisement

At the end of Israel’s War of Independence, Ben-Gurion dismembered the best fighting unit that took part in the war, the Palmach. He feared that the Palmach was heavily influenced by Mapam, a Marxist party that rivaled his own party, Mapai. As a result, the Israeli army had no well-trained offensive units in early 1950. It suffered a humiliating defeat by Syrian forces at Tel Mutila in May 1951. Sharon, in effect, supplanted the Palmach with the paratroopers. At first, he created a daring unit of fifty fighters (Unit 101); he then expanded its scope and combined it with a battalion of three hundred paratroopers to create a fighting brigade of some 1,200 fighters. These may seem like small numbers, but they had immense influence. Under Sharon’s leadership, and with Dayan as chief of staff, the army rekindled the fighting spirit that had been extinguished after 1948.

How good was Sharon as a general? Many years ago, I posed this question to Matti Peled, a fellow general who knew him well. Though their political ways radically diverged, with Peled moving to the far left and Sharon to the far right, they still retained a measure of mutual respect and affection. Peled’s answer resembled the famous line from Mother Goose: When he was good, he was very, very good, but when he was bad he was horrid. Sharon was good, Peled said, when his ego was not involved; he was bad when he let his ego get in the way.

For a long time the dominant theme of Sharon’s life could be summarized as “Always escalate.” This was true in his military thinking, as well as in his confrontational style. His deep belief was that escalation that baffled normal people would serve him well. It was only when he became prime minister that he stopped escalating. Most importantly, he stopped escalating demands that would affect Israel’s relationship with the United States. He ostensibly accepted George W. Bush’s “road map,” which he hated, and he yielded to Condoleezza Rice and Bush by agreeing to hold elections in the West Bank and in Gaza. He thought their need to show that democracy was working not only in Iraq but also in the Palestinian Authority was downright stupid; but he accepted their request so as not to antagonize the US administration.

Sharon’s withdrawal from Gaza was partly, but only partly, a response to the American expectation for some significant move. He insisted, however, that the withdrawal would be a unilateral act by Israel with no PLO cooperation, a cooperation that could have helped in blocking the rise of Hamas in Gaza. This was all in sharp contrast to the days when Sharon was viewed by Bush Sr. and Secretary of State James Baker as persona non grata in Washington.

A close friend of Sharon’s family once said to me: “Sharon is a kept man.” This was true from the time he bought the largest ranch in Israel with money given to him from a wealthy friend, while he was still living on a modest military salary. By this criterion—of having rich friends pay for a luxurious way of life—the list of kept men in Israel is substantial. But as in so many other things, Sharon was one of the first. Indeed, when it came to the pursuit of real estate, Sharon never stopped at a red light (he barely escaped indictment for bribery in 2004). But was he, at the end of his political life, willing to stop at the red light flashed by Palestinians?

Sharon’s robust sense of concreteness always left his intentions to be cast in concrete. He built the massive separation wall in the West Bank, even though the original idea for it was Labor’s and he initially dismissed it because he thought that it would not be effective. Once he adopted it, however, it became his idea, and he was again in his element—hunching over maps, devising lines on the ground. Under his guidance the wall deviated from the Green Line and encroached on Palestinian land, adversely and directly affecting the lives of some 900,000 Palestinians. Sharon didn’t believe that “good fences make good neighbors,” but he tried to sell Robert Frost’s grossly misused line to George W. Bush. Sharon may have believed in good fences, but he never believed in good neighbors—especially if they were Arabs. I believe that by building the separation wall, he tried to unilaterally draw Israel’s permanent borders, while leaving open the question of the future on the other side.

Advertisement

Before the Yom Kippur War in 1973, my friend the writer Amos Elon accompanied Pinchas Sapir, Labor’s powerful finance minister, on a visit to Sharon in Sinai. It was a scorching day, and Sapir was exhausted, but Sharon, who was very keen on impressing Sapir, took him for a ride. He wanted to show Sapir that he could create wonderful roads in the desert on a tight budget. “Well, well,” Sapir said, “but where do these roads lead?” Sapir, the shrewd Labor dove, had a suspicion: though they may have been well paved, Sharon’s roads led nowhere.

This Issue

February 20, 2014

Iran: A Good Deal Now in Danger

The Hidden Polio Epidemic in Syria