Among the wives of famous men who languished in the Gulag, few had a more tragic tale to tell than Lina Prokofiev, the wife of the composer, who in 1948 was sentenced to twenty years in the labor camps of the far north for “treason to the motherland.” Soviet Russia was not her motherland. Born in Madrid, she had grown up mainly in New York, where she met Prokofiev, who had fled there to escape the Bolshevik Revolution, in 1919. Lina had spent only a few childhood summers in her mother’s native Russia when she went back there with her homesick husband, first to visit, and finally to live with their two sons in 1936. It was a bad time to return.

After her release, Lina rarely spoke about the camps, not even after she left the Soviet Union in 1974. Although she gave interviews to journalists, she “perfected the art of evasion” and wrote only a few “scattered notes” of her autobiography, according to Simon Morrison, a Princeton music history professor, who was given special access to the family’s private papers for this revealing book, which casts Serge Prokofiev in a troubling new light.

1.

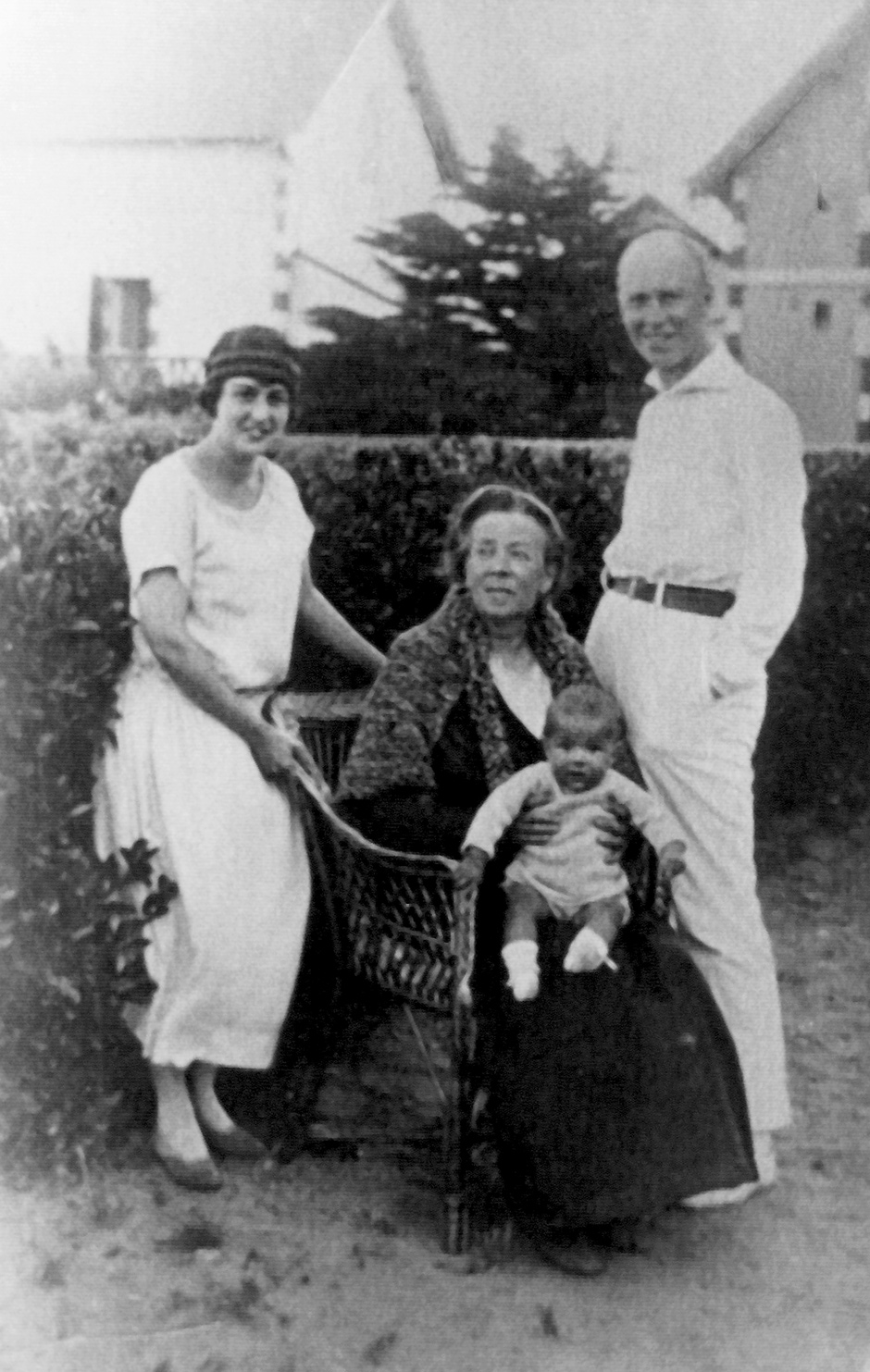

Along with Berlin and Paris, New York was the largest center of the Russian emigration after 1917. The city had three quarters of a million Russians by the time Prokofiev arrived, via Japan and California, in August 1918. Lina was the daughter of two struggling singers, Juan Codina and Olga Nemïsskaya, who had performed in Russia, Switzerland, and Havana before settling in Manhattan, where they had good connections in Russian émigré circles. Lina was working in the New York branch of the Moscow People’s Bank where the young composer, just twenty-seven, six years older than Lina, would come to wire money to his mother, who was stranded in southern Russia, then engulfed by civil war between the Red and White armies. Prokofiev was earning handsome fees from his piano recitals. Lina met him in the green room after one of them. The tall, blue-eyed, and blond composer was surrounded by beautiful women.

At first she found him “vaingloriously rude” and “said so to his face,” according to Morrison. The child of prosperous and doting parents, Prokofiev had had instilled in him from an early age an unshakable belief in his own genius and destiny. By the age of thirteen, when he entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory, he already had four operas to his name. In his diaries of these student years he is always thinking about what he needs to do to advance his career.1 In New York, he was the “lion of the musical revolutionists,” according to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, but the generally conservative American critics preferred the romantic style of Sergei Rachmaninov, who had also just arrived from Soviet Russia. Years later, Prokofiev recalled wandering in Central Park and

thinking with a cold fury of the wonderful American orchestras that cared nothing for my music…. I arrived here too early; this enfant—America—still had not matured to an understanding of new music. Should I have gone back home? But how? Russia was surrounded on all sides by the forces of the Whites, and anyway, who wants to return home empty-handed?2

Gradually Lina fell in love with the self-obsessed and narcissistic composer. She was attracted by his genius and fame and wanted to be part of his artistic life—his muse perhaps, though she also had ambitions as a singer—and thought that she could be the one to break through his cold exterior. Beautiful and vivacious, she saw off several rivals for his affections. There was Dagmar Godowsky, a silent film actress who would later be romantically attached to Rudolph Valentino, Charlie Chaplin, and Igor Stravinsky; the young actress Stella Adler (later known for her studio of acting in New York); and the soprano Nina Koshetz, an old flame from Serge’s student days, who sang the witch’s part in the premiere of his opera The Love of Three Oranges in Chicago on December 30, 1921.

By this time, Prokofiev had left New York for Paris, where his mother, exhausted, sick, and almost blind, had settled after fleeing Bolshevik Russia with the defeated White Army. Lina followed him. She aimed to launch herself as a singer in Europe, perhaps to bring her closer to Serge, perhaps in the hope that he would help her career, though, judging from his diary, he had doubts about her voice, and her performances, if not with him, were limited to the provincial stage and cabarets. He was keen to have her as a lover, and as a nurse for his mother, but he did not want to marry her. He saw marriage as a “heavy stone attached to my foot,” he wrote in his diary.3 Morrison cites a letter of July 9, 1922, in which Serge told Lina that he was “committed to his music—not to any person—and that he was not prepared to consent to marriage if it was not inscribed in his heart.”

Advertisement

In the end the matter was decided when Lina became pregnant. They were married in Ettal, Bavaria, where they had gone while he struggled to complete The Fiery Angel, in October 1923. The marriage quickly settled into a pattern—she serving him while he locked himself away to work.

If in New York he had been second to Rachmaninov, in Paris he was ranked behind Stravinsky, the favorite composer of the all-important patron Sergei Diaghilev. Prokofiev liked to write for the opera, an interest that stemmed from his love for setting Russian novels like Dostoevsky’s The Gambler and Valery Bryusov’s The Fiery Angel to music. But Diaghilev had famously declared that the opera was “out of date.” The Ballets Russes had been founded on the search for a nonverbal synthesis of the arts—dance, mime, music, and visual arts but not literature. Stravinsky, for his part, was committed to the ballet, an art form that enjoyed enormous prestige in the West as quintessentially “Russian.”

Encouraged by Diaghilev, Prokofiev composed the music for three ballets. The Buffoon (1921) was a moderate success, though it rankled Stravinsky, who plotted to turn the arbiters of musical taste in Paris (Nadia Boulanger and Les Six—the composers Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc, and Germaine Tailleferre) against Prokofiev. The second, The Steel Step (1927), a fantastical representation of the new Soviet society, was denounced by the White Russian émigrés as “Kremlin propaganda,” although in fact it was Diaghilev’s idea. Only the third of these Ballet Russes commissions, The Prodigal Son (1929), was an unqualified success. Its theme was close to the composer’s heart.

Isolated from the émigré community in Paris, Prokofiev began to develop contacts with the Soviet musical establishment. In the relatively relaxed cultural atmosphere of the 1920s, the Bolsheviks attempted to build links to Russian artists in the West, regardless of their political affiliations. In 1925, the Party’s Central Committee invited Prokofiev and his wife to travel to Moscow to mark the twentieth anniversary of the 1905 Revolution. They were hoping he would write the music for a propaganda film about the revolutionary events, which Lenin had described as a “dress rehearsal” for October 1917.

Prokofiev declined. He did not want to ruin his chances with the Paris émigrés. But two years later he agreed to make a concert tour of the Soviet Union. In a way that Lina could not fully understand, he longed to go back to his native land, to renew contact with his childhood friends, with the Russian language, Russian songs. As Morrison explains:

Lina had no point of reference for her husband’s longing beyond his sardonic, ill-tempered assessments of his Parisian competition and occasional declarations of weariness with life on the road. His longing was existential—for a guild of like-minded composers, a support network, the inspiration that direct access to Russian culture, of the distant and recent past, had given him.

The 1927 Soviet tour reinforced his longing to return. Prokofiev was thrilled by a sparkling production of The Love of Three Oranges at the Marinsky Theater, while the adulation he received for his recitals in Leningrad and Moscow made him feel that only in his native land would he be recognized as Russia’s greatest living composer. The Soviet authorities pulled out all the stops to lure him back for good. Anatoly Lunacharsky, the commissar of culture, tried to persuade him to return by citing Vladimir Mayakovsky’s famous “Letter Poem” to Maxim Gorky in which he had asked why the writer lived in Italy when there was so much to do in Russia. Mayakovsky was an old acquaintance of Prokofiev. Another of his old friends, the avant-garde director Vsevolod Meyerhold, talked enthusiastically of new collaborations to realize the Russian classics on the stage.

Prokofiev made further trips to the Soviet Union in 1933, 1934, and 1935. At a time when interest in his music was declining in the West, he was seduced by the lucrative commissions he received from the Soviets for operas, ballets, and film scores, and, as Morrison notes, convinced himself that “to rescue his career as a theatrical composer, he needed to shift his sphere of operations from Paris to Moscow.” Politically naive, he was undeterred by the sudden ending of the liberal cultural policies that had allowed the avant-garde to flourish in the 1920s, and by the deadening conformity imposed on Soviet artists by the socialist realist doctrine after 1932.

Politics meant little to Prokofiev. He thought his music was above all that. He assumed that he could return to the Soviet Union and live there unaffected by Stalin’s policies.4 Even the attacks on Dmitry Shostakovich and his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in two Pravda editorials of January 1936 did not put Prokofiev off. Shostakovich had been accused of writing music that was inaccessible to the masses; but Prokofiev was confident that his self-imposed aesthetic of “lightness” and “simplicity” would earn him the approval of the Stalinist regime.

Advertisement

Lina’s instincts told her otherwise. But she convinced herself that the clampdown in the arts was temporary and “would not trouble them,” Morrison observes; she told herself that “it was all just a matter of complex internal politics.” Her own ambition played a part in this delusion. She was tempted by the promise of performances on Soviet radio to revive her singing career. She was certainly more willing to move to Moscow than she would admit, “in the bleak light of hindsight,” toward the end of her long life, when she claimed she had been forced to do it to satisfy her husband’s ambitions. Nonetheless, she followed him to Moscow on the flawed assumption that she could return to France at any time if things turned out badly in the Soviet Union—and therein lies her tragedy.

2.

In July 1936, the Prokofievs took up residence in a spacious new apartment in Moscow. They had a housekeeper and a series of nannies for their boys, Svyatoslav (aged twelve) and Oleg (seven). Even by the standards of the Soviet elite, their lifestyle was extravagant. Prokofiev had a blue Ford imported from America and a chauffeur. He wore tailored suits with brightly colored ties, and Lina dressed in expensive furs and the latest fashions from Paris. In many ways they lived as foreigners, refusing to exchange their Nansen (League of Nations) passports for Soviet papers in the belief that they could leave with them.

It did not take long for the exit doors to shut. Within months of their arrival the Great Terror erupted. The artistic freedoms promised by officials to Prokofiev were soon revoked. Many of his more experimental works, including the long Cantata for the Twentieth Anniversary of the October Revolution, were banned as “formalist” and “incomprehensible” to the masses, the same charges that had been made against Shostakovich, while his revised score of Romeo and Juliet was severely criticized.

Prokofiev was “badgered into submission,” Morrison argues. He wrote “mass songs” in praise of Stalin and other Soviet leaders. During concert tours of the United States he sang the praises of the Soviet Union in interviews with journalists. On his last trip to New York, in 1938, he turned down an offer from Walt Disney to work in Hollywood, insisting on returning “to Moscow, to my music and my children.” He was not allowed to go abroad again.

All this placed a huge strain on his relations with Lina, who now realized that the move to Moscow had been a terrible mistake. According to Morrison, she dreamed of going back to France or the United States, “with or without her husband.” There were stormy arguments. Her career had not taken off as she had hoped. She had been denied membership of the musicians’ union after singing badly on the radio. Serge could or would not help her with the musical authorities.

In 1938, he started an affair with Mira Mendelson, a twenty-three-year-old student at the Gorky Literary Institute in Moscow and the daughter of well-connected government workers.5 This, it seems, was not his first affair.6 But it was more serious than previous trysts. Unlike Lina, who needed his attention and support, Mira was prepared to sacrifice herself for him. With her literary skills she could assist him in his art—his first love—or at least serve him as a secretary—in a way that Lina was not able or prepared to do. Mira helped him write the libretto for his operas Betrothal in a Monastery (1940) and War and Peace (1942). Sympathizing as he does with Lina, Morrison perhaps underestimates the attractions of a woman such as Mira to a self-obsessed creative genius like Prokofiev.

On March 15, 1941, Serge walked out of the marriage, leaving with a suitcase to join Mira in Leningrad. “He thought enough of his wife to summon a physician, to ensure that she was cared for,” wryly comments Morrison. When the German invasion began, three months later, Serge and Mira were evacuated to the Caucasus, while Lina and the boys stayed behind in Moscow, sheltering from the bombs. Out of feelings of guilt and concern Prokofiev offered to arrange their evacuation by a special train to the Caucasus, but Lina rejected the “humiliating” proposal. She survived the war by working as a translator for Sovinformbyuro, the wartime propaganda agency of the Soviet government, though rations were so small that she lost ten kilos from her tiny frame by May 1942, when in despair she wrote to Serge to ask for help to feed their “chronically malnourished” sons. He sent money from his royalties.

By 1945, Lina was desperate to leave the Soviet Union. Taking advantage of her husband’s fame, she became a regular guest at cocktail parties in the British, French, and US embassies, and went on several dates with a British diplomat in her efforts to obtain an exit visa for herself and the boys. It was a high-risk strategy. As the cold war intensified, any contact with a foreigner was likely to invite the attention of the police. Hotels, restaurants, and foreign embassies were under constant watch, and the jails were filled with women who had been seen meeting foreign men.

Her arrest took place on February 20, 1948. Taken to Moscow’s notorious Lefortovo prison, she was beaten and deprived of sleep during three months of interrogation, until she confessed to completely trumped-up charges of stealing documents from Sovinformbyuro and passing information to foreign embassies—charges that would get her twenty years for “treason” in a fifteen-minute trial before a Military Collegium on November 1.

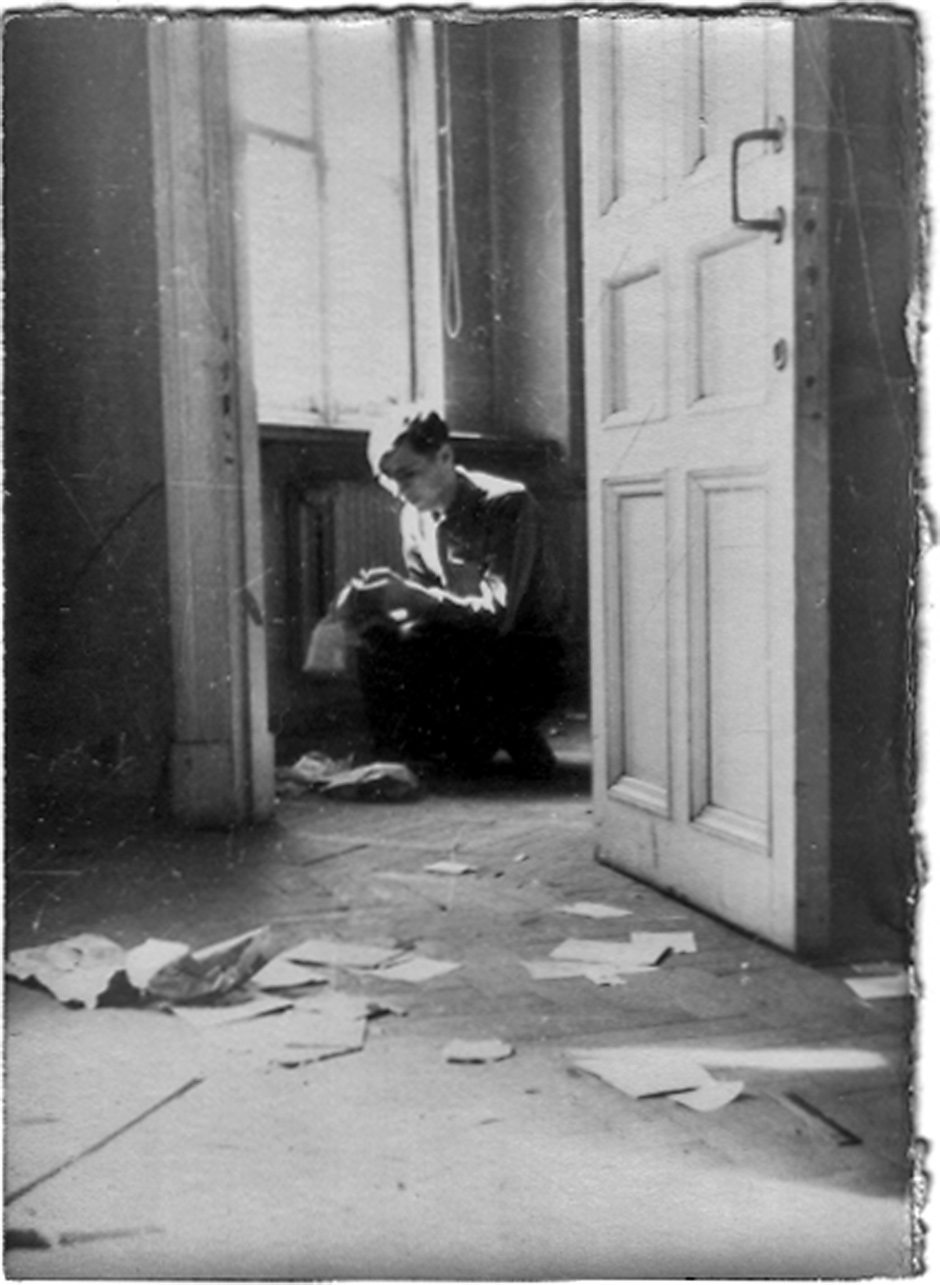

Morrison provides a harrowing account of the police search of Lina’s apartment. Svyatoslav and Oleg watched the police help themselves to whatever took their fancy (a Goncharova painting was taken off by the female officer in charge). Left on their own in the empty apartment, the boys went off to find their father in Nikolina Gora, a dacha suburb of the Soviet elite, where he was living with Mira, whom he had married only a few weeks before (Serge had not divorced Lina but in November 1947 a Moscow local court had ruled absurdly that their marriage in Ettal was null and void because it was not registered with the Sovet authorities).

There was nothing Serge could do to help Lina. On February 10, 1948, he had been included, along with Shostakovich, in a list of Soviet composers criticized by the Central Committee for their “formalist” and “inaccessible” music. Nearly all the works Prokofiev had written in Paris and New York were banned from the Soviet concert repertory, depriving him of “almost his entire income,” according to Morrison. Until his death (on the same day as Stalin) in 1953, Serge and Mira lived in virtual seclusion.

Lina spent the first four years of her sentence at Inta, a special-regime mining camp in the Arctic Circle, where she was lucky to be given work inside—first in the hospital and then as a secretary in the administration—rather than in freezing temperatures. She even sang in a musical ensemble made up of prisoners that toured the Gulag settlements of the Far North. In 1952, she was moved a hundred miles south to Abez, part of the Pechora camp complex, where conditions were marginally better and she was allowed a visit from Oleg. From the camps she “did not write to Serge, and he did not write to her,” records Morrison, “though he sent money to her through Svyatoslav and Oleg. She had dreams about him, and even once thought she saw him in a brigade of male prisoners. He must have been arrested, she concluded, because of her.”

Lina’s devotion to her husband was remarkable. Released in 1956, she fought hard to have the annulment of their marriage reversed by the Soviet Supreme Court, which ended up recognizing both the marriages and distributing the composer’s estate among his two widows and two sons. Lina outlived Mira, who died in 1968. Eventually, in 1974, she was allowed to emigrate. She lived mainly in London and Paris until her death in 1989.

During these last years, a time of growing interest in Prokofiev’s music in the West, she became his cultural ambassador, attending concerts, donating papers to archives, and giving interviews to journalists. But she never spoke openly about the camps—she remained too afraid—and in that sense she never really escaped the Soviet Union. Nor at the end was she able to make sense of her husband’s life, or their life together and apart: her devotion to him blinded her. In the interviews she gave, Morrison observes in the final pages of this well-researched and moving book, she left “the impression of someone seeking to prevent anyone from reaching the obvious conclusion: that she was a tragic victim of Serge’s genius and the self-delusion that he shared with his nation.”

-

1

Sergey Prokofiev, Diaries, 1907–1914: Prodigious Youth, translated and annotated by Anthony Phillips (Cornell University Press, 2006). See my review in these pages, May 10, 2007. ↩

-

2

Sergei Prokofiev, Materialy, dokumenty, vospominaniia (Moscow: Gos. muzykal’noe izdatel’stvo, 1961), p. 166. ↩

-

3

Sergey Prokofiev, Diaries, 1915–1923: Behind the Mask, translated and annotated by Anthony Phillips (Cornell University Press, 2008), p. 592. ↩

-

4

There is a revealing entry in the third and final volume of Prokofiev’s diaries, which have now been published in English. Hearing that Stalin had been present at a concert of his music and had referred to him as “our Prokofiev,” he wrote on March 5, 1929: “This is splendid: now I can go to Russia with nothing to fear.” Sergey Prokofiev, Diaries, 1924–1933: Prodigal Son, translated and annotated by Anthony Phillips (Cornell University Press, 2012), p. 789. ↩

-

5

For a long time it was rumored that she was the niece of Lazar Kaganovich, the minister of heavy industry and a close friend of Stalin, suggesting that Prokofiev was politically trapped, compromised, or protected through the affair. But there is no factual evidence to support this claim, and Morrison omits to mention it. ↩

-

6

It has been suggested that on his Soviet tour of 1934 he had an affair with Eleonora Damskaya, a harpist he had known since his student days at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. In 1935, Eleonora gave birth to a son who grew up to bear a striking resemblance to Prokofiev. See utro.ru/articles/2005/07/21/460372.shtml and “Prokofiev and his Women,” The Voice of Russia, August 7, 2007. ↩