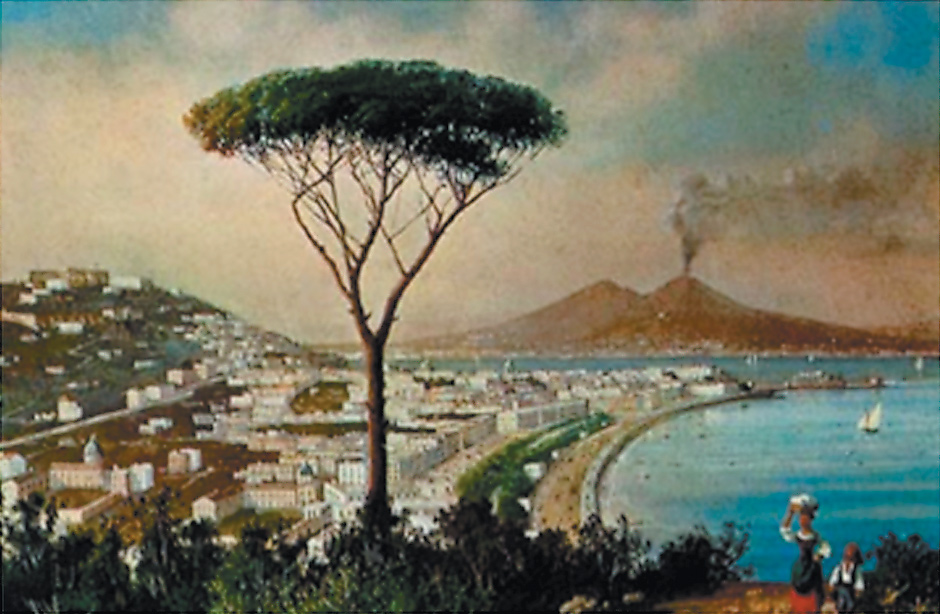

The French writer Marcel Brion subtitled his 1960 study of Pompeii and Herculaneum “The Glory and the Grief,” a phrase that captures the enduring mystery of these two ancient Roman towns, both buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. The explosion itself was a majestic sight, if not exactly glorious; we have the word of an eyewitness, Pliny the Younger, who compared the pillar of smoke created by the mountain’s pulverized core to an umbrella pine, the soaring, graceful local tree that virtually symbolizes the Bay of Naples.

The umbrella pine was so perfect an image for a volcanic cloud that nearly every later witness to an eruption of Vesuvius has revived it. When the mountain returned to violent life in 1631 after centuries of quiet, the tree-shaped cloud appeared again:

The smoke narrowed into the shape of an umbrella pine, and gradually increased so much that, as observers have reported, it shot up to three hundred miles into the air—the earth seemed to want to mix with the sky. This was followed immediately by a huge eruption of fiery globes, and then by a subterranean rumbling and crashes like those of horrible thunder, then by continuous flashes and lighting, and then huge amounts of blackish, ashy sand poured forth, which first seemed to present a moist surface, but quickly, as the sun dried it, it changed its color into bright white puffs, rather like silk.1

The volcano’s most recent eruption occurred in 1944, at the height of World War II. The British officer Norman Lewis saw the umbrella pine of smoke, followed by a show of geological pyrotechnics:

Fiery symbols were scrawled across the water of the bay, and periodically the crater discharged mines of serpents into a sky which was the deepest of blood reds and pulsating everywhere with lightning reflections.2

But these glorious, treelike bursts of celestial fire also brought filthy clouds of debris in their wake, and the rotten-egg stench of brimstone. In 1767, William Hamilton, the English envoy to Naples, was caught by a secondary explosion as he explored an actively erupting Vesuvius:

The earth shook, at the same time that a volley of pumice stones fell thick upon us; in an instant, clouds of black smoak and ashes caused almost a total darkness; the explosions from the top of the mountain were much louder than any thunder I ever heard, and the smell of the sulphur was very offensive.

The umbrella pine of smoke and the celestial fireworks provided a prelude to more terrifying cataclysms. In 79, as Pliny the Younger reports, the glorious waters of the Bay of Naples turned into a churning maelstrom (as it emptied, the volcano sent shudders through the earth), and then the mountain spewed its most deadly charge of all: spurts of solid debris suspended in superheated gas. These gaseous suspensions, called pyroclastic flows, behaved like liquid rivers, but they moved much more swiftly than liquids, coursing down the mountainside as fast as a speeding Ferrari, killing every living thing in their path.

In Herculaneum, it was the first of these terrible surges that took the lives of three hundred people huddling at the seashore in hopes of rescue; a few seconds before, it had carbonized all the food, furniture, trees, papyrus books, balconies, shutters, and beams in the city. The scorching blast moved quickly enough to catch the victims by surprise, vaporizing them before they had time to register fear or pain. As the cooling gases of this surge and the ones that followed bled into the atmosphere, the pyroclastic silt they left behind congealed into a dense volcanic rock, sealing Herculaneum away from the rest of the Roman world.

Pompeii, a few miles farther south, stood downwind from Vesuvius on the day of the eruption. The volcano shot out a rain of pebbles called lapilli, fine-ground remnants of the mountain’s exploded core. The airbone gravel blew southward on the volcanic gusts and prevailing winds, piling up in corners and bouncing off roofs and heads before shrouding the city in a layer of rough, reddish gravel. Here, too, a series of pyroclastic surges followed, sweeping through the city on waves of poisonous gas, smothering huddled groups of refugees and a dog on its leash seconds before their muscles shrank on their bones and twisted them into the agonized positions in which excavators would find them centuries later. Like the victims in Herculaneum, these people and the dog had certainly felt dread, and fear, and severe discomfort before they died, but not the actual pain of incineration; nerves and brains dissolved too quickly to register any final feelings.

The inanimate parts of the two cities, on the other hand, survived to a remarkable extent, although some yellow-painted walls turned red in the heat of the pyroclastic surges. Wooden fixtures in Pompeii disintegrated completely (whereas in Herculaneum they were left intact but carbonized), but doors, shutters, and bodies left hollow prints in the hardened volcanic debris that settled around them.

Advertisement

The disaster was great enough to have real effects on Rome itself. It certainly cooled the Roman enthusiasm for vacationing on the Bay of Naples, and one contemporary writer, the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, went so far as to compare the eruption of Vesuvius to the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. And though the buried cities had disappeared from view, they never entirely disappeared from memory. A popular novel of 1504, Jacopo Sannazaro’s Arcadia, includes a visionary tour beneath Vesuvius, conducted by a nymph, who tells the hero Sincerus:

The burnt and liquefied stones still bear clear witness to anyone who sees them, and beneath them who would believe that there are populations, and villas, and noble cities that lie buried? Truly there are, and they were covered by ruin and death, like the one that we see here before us, a city once celebrated beyond doubt in your countries, called Pompeii…. Certainly it is a strange and horrible way to die; to see people snatched from the ranks of the living in a second.3

As Sannazaro and his readers already recognized, the glory and grief of Pompeii and Herculaneum haunt us because the mortality of these places, and these people, is ours in equal measure. Vesuvius still rears its sullen gray profile above the Bay of Naples, its rim torn ragged by past explosions: in 79, 472, 512, 1138, perhaps in 1500, just before Sannazaro published his Arcadia, 1631, 1660, 1766, 1822, 1836, and 1944.

Archaeologists in Nola, to the northeast of Naples, have discovered the remains of a hut village on the other side of the angry mountain that was buried by an eruption in the Bronze Age, more than a thousand years before the destruction of Pompeii. By now Vesuvius has stood quiet for too long to foresee a gentle reawakening; when it explodes again, as it inevitably shall, the eruption may well take the violent form of the events in 79 and 1631, with an umbrella pine formation and pyroclastic flows, rather than the gentler spills of lava that appeared at regular intervals in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The discipline of archaeology began with the generation of Jacopo Sannazaro’s teachers, in the late fifteenth century, but archaeological excavation of Pompeii and Herculaneum only began in the eighteenth century; first as a series of private efforts, then under direct sponsorship of the king of Naples and his successors in authority, most recently the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities. Herculaneum was discovered by chance when a peasant dug a well and came up with statues before striking water. The site could only be reached by tunneling downward through layer upon layer of hard-packed pyroclastic debris; it was difficult, dangerous work, carried out by convicts of what one Grand Tourist described as “the rascally and villainous sort.”

Paintings were hacked away from walls; marble, bronze, gems, glass, gold, and cameos were requisitioned for the royal collection. Only the slim and athletic dared to go down the excavators’ shafts in a basket to see the remains of the theater and what came to be known as the Villa of the Papyri; one portly Englishman, William Hammond, wrote in 1732 that he “never cared to venture down, being heavy, and the Ropes bad.”4

By 1748, the finds at Herculaneum had begun to peter out, and the king turned his attention to other sites, including Pompeii. There the piles of lapilli could be moved far more easily than the hard pack at Herculaneum. Furthermore, excavation could take place in the open air rather than down mephitic tunnels. So could the guided tours that quickly became an indispensable part of a visit to Naples. And because the capital city was also a thriving intellectual center, the excavators began to publish their results with admirable dispatch.

As a result, the history of excavation and scholarly publication of these two remarkable sites now extends back nearly three hundred years, from the engraved folios of the royal publication Le Antichità di Ercolano Esposte (1757–1792) to the comparably active work sponsored in recent years by the Superintendency of Pompeii and Herculaneum and the international Herculaneum Conservation Project. At the same time, visitors as disparate as Mozart, Madame de Staël, Dickens, Freud, Renoir, and Picasso have drawn inspiration from the combination of an uncannily beautiful natural setting, an uncanny natural disaster, and the astounding range of human activity captured and preserved among the ruins.

In the summer of 2013, the British Museum brought the buried cities to London in an immensely successful exhibition called “Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum,” organized by Paul Roberts, senior curator and head of the Roman Collections, who also wrote the excellent catalog.5 Roberts focused attention on the experience of life in an ancient Roman house, a theme that also guides Herculaneum: Art of a Buried City, a spectacular collaboration among Maria Paola Guidobaldi, director of excavations at Herculaneum, the scholar Domenico Esposito, and the photographer Luciano Pedicini. This large folio volume provides floor plans, detailed descriptions, and evocative illustrations: Pedicini’s careful choice of lighting and viewpoints makes even such well-known objects as the bronze statues from the Villa of the Papyri look startlingly new.

Advertisement

The buried cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum remain our most complete surviving sources of physical information about ancient Roman domestic life, supplemented by written sources like the architectural treatise of Vitruvius, which tells us how houses were laid out and decorated some eighty years before the eruption. Then there is the cookbook of Apicius, which tells us what went on in the kitchen some three or four centuries later, and the lurid fictional account of a nouveau-riche banquet in the Satyricon of Petronius, which allows us to people the empty, ruined dining rooms of the archaeological sites with an entertaining, if appalling, cast of characters contemporary with the last days of Pompeii. Because our sources are so spotty and so enigmatic, there is always something new to discover about something as complex as an ancient civilization, some point on which to change our mind.

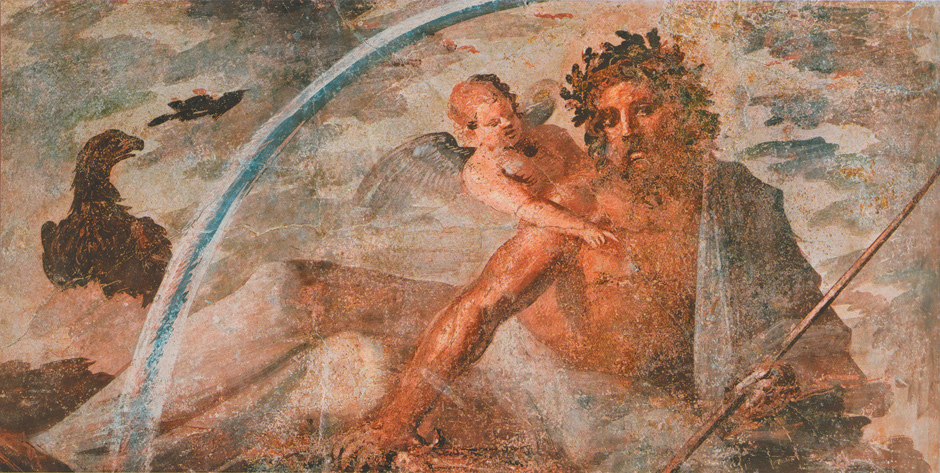

For its London venue, the British Museum recreated a generic ancient house, but in fact, as both these books make clear, the two settlements on the Bay of Naples served two different purposes and their houses reflect that distinction. Herculaneum was a suburban resort; the sprawling villas perched on its seaside cliffs belonged to wealthy senators from Rome and local magnates who came to escape the crowds and smells of city life, and created a refined vacation village dedicated to the hardworking hero Hercules. High above its buried ruins, wealthy Neapolitans of the eighteenth century would build villas of their own along what came to be known as the “Golden Mile.”

Pompeii, on the other hand, was an industrial town, its suburbs home to factories, port facilities, and villas that were more working farms than leisurely retreats, its city blocks packed densely with houses for people of rich, poor, and middling incomes. Pompeii’s patroness, appropriately, was Venus, goddess of sex, love, fertility, and prosperity, the immemorial comforter of sailors. The houses of Herculaneum, therefore, are sumptuous and refined; those of Pompeii exhibit more variety, including slapdash remodeling and affectingly human clutter—how many birdbaths did the brothers Aulus Vettius Conviva and Aulus Vettius Restitutus really need in a single courtyard? (Six, apparently.)

Every one of these ancient houses enjoyed amenities that only a mild climate, fertile soil, and access to the sea could provide. Food was good and abundant, trade brisk and exotic, and much of life could be lived in the city’s streets and squares. Houses were designed as suites of rooms clustered around an interior courtyard, the atrium. The atrium itself could be totally enclosed or open to the sky; usually the latter. Larger houses also boasted a second, more private colonnaded courtyard, to which the Romans gave a Greek name, peristyle (“surrounded by columns”). Even houses too modest to permit an atrium or peristyle might have a little air shaft decorated with images of trees, gardens, or water nymphs to suggest, however modestly, a sylvan retreat within the home.

The normal construction materials were brick and blocks of the local golden volcanic stone, often set within timber frames to provide excellent protection against earthquake. The smooth plaster walls were painted in brilliant colors and then polished with melted wax to a gleaming sheen, still preserved in many places despite the pyroclastic inferno that rampaged through these buildings. Ceilings were sometimes coffered in wood or arched over with colorfully stuccoed masonry vaults; remarkably, a set of elaborately carved coffers has survived from Herculaneum. The most opulent floors were decorated with intricate mosaics, sometimes with insets by “Old Masters,” most of them Greek or Egyptian, or inlays of colored marble (called opus sectile, “cutwork”).

More modest householders laid down brick in a herringbone pattern or used a mixture of crushed brick and stone set in mortar (Vitruvius notes that this kind of floor retains heat well and never shows wine stains). The rooms of the large villas were carefully arranged to take advantage of sea breezes in summer; portable bronze braziers, sculpted with mythological figures, provided warmth in winter (and insulation was bad enough to stave off the threat of carbon monoxide poisoning). Picture windows are common in the seaside villas at Herculaneum, and every private dining room aimed to provide something pleasant to look at while eating, whether it was an interior garden, a fountain, or the sea.

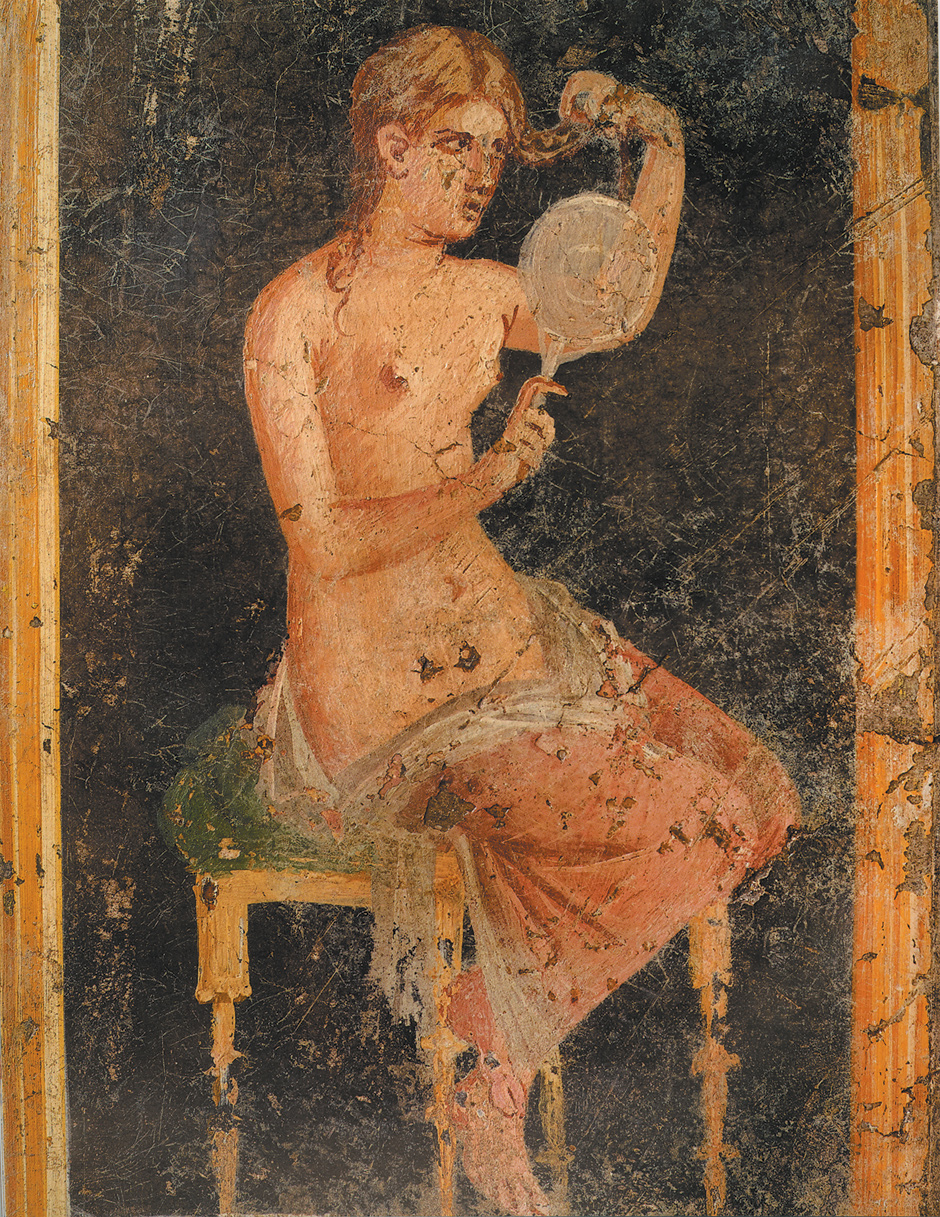

Within this basic pattern, nearly every house in Pompeii and Herculaneum has its own unique design. Some of these dwellings were as much as two centuries old at the time of the eruption; many more were in the process of remodeling after a devastating earthquake in 62 or 63, a first sign, in hindsight, that the volcano was growing restless. Their frescoed walls are one of their most astonishing features. Early visitors to Herculaneum were shocked by what they saw, both because of the decor’s riotous exuberance and its scenes of uninhibited sex. Roberts reminds his readers that the rampant phallic symbolism represents fertility and prosperity, but it also represents a view of human intimacy radically different from the Christian culture that was beginning to gather force in those very years. One disappointed Englishman wrote back to the Royal Society in 1751:

The designs of the greatest part of these paintings are so strange and uncouth, that it is difficult, and almost impossible, to guess what was aimed at. A vast deal of it looks like such Chinese borders and ornaments, as we see painted upon skreens. There are great numbers of little figures, dancing upon ropes; some few small bad landscapes; and some very odd pieces, either emblematical, or perhaps only the painter’s whim.6

Can he really be talking about the same figures that we see in Luciano Pedicini’s captivating photographs? Not always; some of the houses shown in Herculaneum: Art of a Buried City are recently excavated, but many of these works are precisely what the anonymous Englishman saw and disparaged. Viewers’ reactions to ancient Roman painting have definitely changed; today these fanciful figures beguile our sensibilities as completely as they captivated the sixteenth-century artists who adapted the same style, calling it “grotesque” because most of the surviving examples were found in underground “grottoes,” that is, buried ruins. As the English correspondent writes from Herculaneum, it is “difficult, and almost impossible, to guess what was aimed at” by these riotous capers of the pictorial imagination, but Maria Paola Guidobaldi and Domenico Esposito pin them down in meticulous descriptions, finding, remarkably, the right words for every last detail. These accounts make for slow, careful reading, but close description is the only sure way to open our eyes to the full brilliance of such intricate designs, and the two archaeologists’ abilities at putting shapes into words are extraordinary (the book is also exceedingly well translated).

The artists who worked in Herculaneum were probably the same ones who worked in Rome and Naples, that is, they were the best in the business. Their subjects range from carefully chosen mythological scenes (Hercules appears often in Herculaneum and Venus in Pompeii) to portraits of householders to extravagant architectural fantasies. Writing in about 25 BC, Vitruvius railed against the evils of modern painting and the moral decay that would ensue from showing structures and monsters that could never occur in nature, but most ancient Romans loved the new style as much as Raphael and Michelangelo would love it again in the Renaissance.

On the other hand, as Roberts points out, some aspects of ancient Roman life are almost impossible to imagine today. The Romans may have been superb hydraulic engineers, but most home latrines were simply a hole above a cesspit that was periodically emptied by specialized workers (who were none too accurate in carrying out their tasks). The usual place for these facilities was under the stairs or in a corner of the kitchen, often with no partition dividing the privy from the cooking area. No S-curved pipes kept the scent of the cesspit in its place and no faucet provided for the washing of hands after accomplishing one’s business. Soap was an unknown invention. As Roberts puts it:

The smells of the cesspit, acrid ammonia from urine and stomach-turning smells of faeces must have found their way into kitchen and home.

The Romans had beautiful, refined baths, but may not have used them daily. Roman women’s fantastic hairstyles were sewn in place and were probably, therefore, none too clean by present-day standards.7

Slavery in Pompeii and Herculaneum was also a cruel fact of life. A current exhibition at the Museum of the Via Ostiense in Rome shows how six Imperial-era skeletons discovered in an ancient graveyard have all been deformed by years of relentless manual labor.8 On the other hand, the Romans were more likely to free their slaves than most owners of human chattel. Roberts suggests, intriguingly, that a growing population of prosperous former slaves was beginning to transform society in Pompeii and Herculaneum when the volcano erupted; many were probably as crass as the freedman Trimalchio in the Satyricon, but many were just as refined as their former masters, if not more so, and they must have brought a cosmopolitan flair to cities that were already an energetic mix of different ethnic and linguistic groups: Greeks, Etruscans, Oscans, Samnites, Latins, and the odd Egyptian.

Pompeii was big enough to have its own gladiatorial arena, the site of a riot between local fans and a group from nearby Nuceria (modern Nocera) in 59 AD, an event commemorated in a wall painting from Pompeii that is now in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples. Most Romans were perfectly content with the gory realities of gladiatorial combat; for many, the most pernicious form of popular entertainment was theater, because it presented fiction, as bad for the soul’s health as paintings of fantastic beasts and improbable architecture. Furthermore, as Vitruvius warns, theater presents a hazard for our bodies, too: sitting still for so long opens up our pores to the noxious exhalations of swamp animals.

The arena games, on the other hand, presented a succession of real situations, designed to edify and instruct the public as it shouted for blood. The games began with displays of human dominion over the animal world in the form of staged hunts, followed by executions of condemned criminals, and culminated in the afternoon with gladiatorial combats, gripping exhibitions of real courage by the most abject of men, and hence, or so the Romans believed, an example and an inspiration to spectators. It was in an arena just north of Naples, at Capua, that the Thracian gladiator Spartacus rebelled against this entire Roman system of enslavement and choreographed cruelty in 73 BC, gathering a band of runaway slaves and gladiators who held their own against the state for two years from a stronghold inside the green, forested crater of Vesuvius. The region around the Bay of Naples could tell tales of glory and grief long before Vesuvius erupted.

Today there are other cataclysms affecting the region and the buried cities, less spectacular, perhaps, than Vesuvius in full pyroclastic glory, but no less destructive: pollution, climate change, greed, ignorance, poverty, political corruption, organized crime. The industrial area of ancient Pompeii lies outside the old city walls, and therefore outside the archaeological site, which has been under government protection since the eighteenth century.

This industrial zone is where a philanthropist named Bartolo Longo founded the modern city of Pompeii in the late nineteenth century, horrified by the conditions of life in the area: rampant malaria, poverty, and banditry (two members of the Camorra, the Neapolitan Mafia, met Longo as he stepped down from the train on his first visit to Pompeii in 1872). In 1880, Longo discovered (and preserved) the remains of an ancient laundry in the foundation trench of his “Economical Workers’ Houses.” In a very different spirit, the remnants of another ancient industrial plant, the most extensive yet discovered in the area, were entombed just last year by the concrete slab of an immense Carrefour supermarket, with the apparent approval of all the local authorities.

Herculaneum, smaller and more manageable, is now protected by an international foundation (the Herculaneum Conservation Project sponsored by the Packard foundation), but Pompeii, like every other museum and historical site in Italy, has struggled on alone, suffering both from the drastic budget cuts imposed on the Ministry of Culture during the two decades (1993–2013) when former prime minister (and convicted felon) Silvio Berlusconi and his party were in power, and from the gross corruption of some of Berlusconi’s local appointees. Notoriously Marcello Fiori, the special commissioner for Pompeii who arrived in 2010, now faces trial for embezzlement and a “restoration” of the ancient theater that local papers have characterized as “an avalanche of [modern] cement.”

Massimo Bray, minister of culture for Prime Minister Enrico Letta (who resigned on Valentine’s Day), has been a welcome contrast, intent on finding special funding for the world’s most famous archaeological site (and a UNESCO World Heritage property). At last, there seemed to be some hope that Pompeii’s worst days as a crumbling, neglected monument of human frailty might be a thing of the past. For all the magnificence of these excellent books and the British Museum’s recent exhibit, there is nothing in the world like the buried cities themselves. One can only hope that the newly appointed Italian prime minister, Matteo Renzi, will take note.

-

1

Athanasius Kircher, Diatribe de prodigiosis Crucibus (Rome: Sumptibus Blasij Deversin, 1661), pp. 30–31. ↩

-

2

Norman Lewis, Naples ’44: A World War II Diary of Occupied Italy (Carroll and Graf, 2005), p. 93; letter of March 19, 1944. ↩

-

3

Jacopo Sannazaro, Arcadia (Venice: Aldus Manutius, 1534), pp. 77–78. ↩

-

4

William Hammond, letter published in “An Account of the Discovery of the Remains of a City Under-ground, Near Naples, Communicated to the Royal Society by William Sloane, Esq., F.R.S.,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Vol. 41 (1739–1741), p. 345. ↩

-

5

The J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu presented an exhibition on Pompeii’s impact on modern culture a few months earlier: “The Last Days of Pompeii Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection,” September 12, 2012–January 7, 2013. ↩

-

6

“Extract of a Letter from Naples, concerning Herculaneum, Containing an Account and Description of the Place, and What Has Been Found in It,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Vol. 47 (1751–1752), p. 157. ↩

-

7

Abigail Pesta, “On Pins and Needles: Stylist Turns Ancient Hairdo Debate on Head, The Wall Street Journal, February 6, 2013, about the work of Janet Stephens. ↩

-

8

“Scritto nelle Ossa: Vivere, Ammalarsi e Curarsi Roma in Età Imperiale,” December 19, 2013–April 30, 2014. ↩