Sometime early in the reign of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia between 1975 and 1979, Rithy Panh, who was thirteen years old, was digging a ditch on one of the regime’s brutal collective farms when he hit his foot with a pick-ax. His wound didn’t seem very serious at first, but “what with the damp earth, the dust, the perspiration, the mud, the stagnant water, and the lack of food and sleep,” it became badly infected. A dose of penicillin would have cured him, but there was no penicillin, and eventually, with his wound suppurating and malodorous, he was sent to a hospital that had been installed in the former prayer hall of a pagoda.

There was another boy there, also wounded, in his case by a blow to the knee, and he became a kind of double, Panh writes, two wounded boys alone, trapped in the nightmarish dystopia of Democratic Kampuchea. Eventually a nurse applied a “black poultice devised by the ‘revolutionary’ laboratories” to their respective wounds. “It was a mixture of leaves, resin, and to tell the truth I don’t know what else,” Panh writes in The Elimination, his unsettling, probing, morally urgent reflection on the Khmer Rouge years. A day later, he scraped the substance away with his fingernails. “It was a mass of glue from hell, a kind of tar under which my injury had grown worse.”

Soon, the other boy was dead, one of the 1.7 million Cambodians, one fifth of the country’s population, who are estimated to have died by execution, hunger, disease, or some other affliction brought on by the homicidal radicalism of the Khmer Rouge, but Panh was able to get to the village where his mother had been ordered to live. She had managed to hoard a small amount of gold, which she exchanged for a single tablet of penicillin, and by grinding this tablet into a powder and sprinkling it on Panh’s wound, she cured him. “A real miracle,” Panh writes, looking back from the vantage point of decades later. “The miracle of science: a trite expression for those who don’t need to believe in it.”

The Khmer Rouge of course claimed to believe in it. But for Panh that poultice summed up the sham of it all, the triumph of pure ideology, which in Cambodia was a leap of faith in the infallibility of the Angkar, the Organization, the mostly invisible but all-powerful ruling clique. In his book, Panh tells of witnessing the horrific death in childbirth of a young woman because a Khmer Rouge “doctor” was incompetent to help her and nobody would fetch the real doctor, a representative of the discredited class who lived nearby. “The young body, scarlet and deformed, was ideology itself,” Panh writes.

Rithy Panh is a forty-nine-year-old writer and filmmaker who over the last twenty years has engaged in what is likely to be the most sustained, penetrating, and affecting investigation of Khmer Rouge Cambodia and its aftermath that we’re ever going to have. His own experience of the Cambodian genocide was searing and personal. Within the first six months after the Communist takeover of the country on April 17, 1975, most of his family members had died, including his father, who had worked in the education bureaucracy in several previous governments, his mother, his younger sister, an uncle, and two young nephews and a niece who starved to death in front of his eyes during the famine induced by the regime’s drastic rural collectivization policies—“small creatures who asked not for a better world but for a portion of white rice.”

He survived a succession of work details in different places in the Cambodian countryside, including one prolonged stint removing the dead from a hospital near the city of Battambang and burying them in a putrid mass grave. He drank water from rice paddies, ate soup made from leaves and bark, killed snakes and devoured them, but he survived, and when the Khmer Rouge fell in 1979, he was able to go to France, where he has lived ever since, though he has spent extended periods in Cambodia chronicling the history of Democratic Kampuchea.

Panh’s major work consists of a dozen or so documentary films that examine the Cambodian tragedy and its aftermath through the experience of people who talked to him. His Paper Cannot Wrap Up Embers is about Phnom Penh prostitutes. Rice People, a portrait of a rural family struggling to survive in the wake of the Khmer Rouge disaster, was submitted in 1995 for an Academy Award for best foreign-language film. L’Image manquante, or The Missing Image, Panh’s most recent film, uses small clay figurines to depict a genocidal movement that left behind few visual images; it was one of the nominees for best foreign language film at this year’s Academy Awards and was released in the United States in March.1

Advertisement

Another recent film, Duch: Master of the Forges of Hell, is an extended portrait of Kaing Guek Eav, aka Comrade Duch, the commandant of the Tuol Sleng prison, the most notorious of the regime’s many centers of torture and death. The film is winnowed from many hours of interviews with Duch, whom Panh met before and during Duch’s trial at the special Cambodian-international tribunal that was set up in 2006 to try the five most senior surviving Khmer Rouge leaders.2 (The film was shown in New York during a Cambodian cultural festival last April.)

Panh’s films, which are strongly influenced by Shoah, Claude Lanzmann’s masterpiece on the Holocaust, attempt to relive the Cambodian revolution though the testimony of participants and witnesses, many of whom Panh brings to the scenes of their past lives where they talk about what happened and reenact it in front of the cameras. The two films under review here have no narration, no explanation of setting except for snippets of historical footage showing, among other things, masses of people running with dirt-filled wicker pans at a vast collective agricultural project. “I create situations in which former Khmer Rouge can think about what they did,” Panh writes in The Elimination, which is a kind of literary companion to the films. “And in which the survivors can tell what they suffered.”

Stalin is said to have joked that a single death is a tragedy, a million a statistic. Panh’s approach is to memorialize that single death, not that he forgets the extraordinary and generally accepted statistic of 1.7 million dead, an average of 1,250 deaths for every day that the Angkar was in power. His focus in both his films and his new book is on the telling but often unexpected details like that poultice, or the ban placed by the regime on the words “wife” and “husband,” because of their supposed individualistic connotations. Panh sustains a kind of distanced, aphoristic anger, mostly of course at the Khmer Rouge itself, but also at the few Western intellectuals who made excuses for it or contended that the charge of genocide is exaggerated and demonizing.

The enduring question about Cambodia is perhaps the same as the question that is asked about other analogous regimes: How did this small group of revolutionaries exercise the psychological and ideological power to persuade others to commit fantastic, unimaginable atrocities? Was it mainly a matter of terror, of dire punishments inflicted against those who refused, or was it indoctrination, propaganda, and fanatical belief? In his study of the German Ordnungspolizei, the special troops that massacred Jews in Poland in 1942, the historian Christopher Browning found that a conventional obedience to authority was sufficient to get otherwise “ordinary men” to do the job of mass killing. No fanatical devotion to Nazi ideology was needed.3

The works of Panh that concentrate directly on this question are his study of Duch and an earlier documentary, S21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine, which was first shown in France in 2003. Panh persuaded former guards, now middle-aged men who in the years since the Khmer Rouge’s fall have slipped back into Cambodian society, to talk about their time as the “comrade interrogators” of the Tuol Sleng prison, which was officially known as Bureau S21. Pahn brings them back to the cells and rooms where they tortured prisoners and forced them to write confessions, after which they were taken by truck to a nearby place called Choeung Ek where they were killed. The former guards describe in detail the grim routines of S21, and they visit Choeung Ek as well where they reenact every stage of the executions.

These fishermen and farmers seem modest, deferential, and nonideological, yet they once faithfully and efficiently carried out the murderous bidding of Duch and the Angkar. There is one major difference between them and the men of Browning’s Reserve Battalion 101. These Cambodian torturers and executioners were recruited by Duch when they were teenagers, and he kept them with him during his entire career as a prison commandant, confident of their loyalty. Their lives were dominated by Duch himself, their patron, teacher, and guide, and they spent them within the sealed world of S21, putting in long, hard days there at the job. In contrast to the German special troops, they could hardly have chosen not to play the part assigned to them by the Khmer Rouge death machine. When it came to the morality of what they were doing, “my thoughts didn’t go very far,” one of them, a man named Thuy, says.

Advertisement

S21 had a distinction that marked it off from the other 157 prisons that were maintained under the Khmer Rouge.4 More people were killed in some other prisons, but those brought to S21 were supposed traitors from within the Khmer Rouge’s own ranks. This made obtaining confessions especially important, and in Panh’s film, the former interrogators describe with remarkable candor the brutal methods they used to get them.

In one especially disturbing scene, a former camp guard named Prak Kanh looks at a photograph of a delicate-looking young woman named Nay Nan. It is not clear how Nay Nan was taken to S21, but often people desperate for the torture to stop simply gave the names of practically everybody they knew; those people were then arrested, and anybody arrested was by definition guilty. Kanh remembers in particular that Nay Nan was beautiful and that he desired her, and he describes his handling of her case. At first, he says, she refused to reply to his questions, “so I asked Duch and Chan what to do,” Chan not identified but evidently another member of the prison leadership. “They said to use hard methods,” Kanh says, so he chose to beat her with branches, one of the approved torture methods, “until she pissed on herself. Then she asked to write her confession.”

Kahn instructed Nay Nan in the form the confession had to take. It had to be like a story, he told her, and it had to include the enemy network that she belonged to and the names of its leaders. So Nay Nan, who worked at a Khmer Rouge hospital, duly confessed to having defecated on the hospital’s supply of rice and on its operating table in order to embarrass the hospital’s leaders. Kanh gave her a choice of three enemy networks that she could admit to belonging to in her “activity of sabotaging the hospital,” the KGB, the CIA, or the Vietnamese, and she chose the CIA. Then this young woman, who was nineteen years old and virtually illiterate, was taken to Choeung Ek and executed.

Kanh and the other interrogators at S21 make no effort to deny the atrocities they committed. They describe every aspect of their work, including the sexual desire they felt for female prisoners. They took fatal amounts of blood from some prisoners, presumably for wounded soldiers at the front, and they executed the children of the supposed traitors to the Angkar. But they say they did what they did because they had to follow orders, or they too would have been tortured and executed. They, too, were terrorized prisoners of the regime condemned to carry out its wishes.

This argument is repeated by Duch himself in Panh’s film about him, though unlike the ordinary prison guards he was an educated man, a former mathematics teacher who joined the revolution by choice and spent years as a devoted follower. Panh’s confrontation with Duch is the thread running through his book and, naturally, it is at the center of his documentary on Duch. Duch turns out to be extremely voluble, eager to talk. While Panh’s cameras moved in close, putting him under a sort of magnifying glass, Duch admits that his “métier” was “to receive men, torture them, interrogate them, and destroy them.” He admits to much else as well—the killing of the children, the taking of blood, the executions at Choeung Ek. He acknowledges that the confessions obtained under torture were false, which, of course, means that he ordered prisoners to be executed knowing that they were innocent of the charges against them.

He explains the concept of what the regime called kamtech, meaning not just to kill but to destroy all trace of the person killed, or, as Duch puts it, “destroy the man, the image, the body, everything,” so that, as Panh describes this in his book, every trace of the earlier existence of an enemy of the regime was wiped away. It was part of the regime’s ambition to start afresh, to destroy the old so that something radiantly new could be put in its place.

Duch’s moral position is the same as that of the guards and interrogators who did the dirty work at S21. As an educated man, he says, a man who taught school and spoke French, he was exactly the kind of person who was slated to be eliminated in the Cambodian revolution, and therefore he could survive only by showing a fanatical, utterly reliable obedience to the Angkar. “In that regime, the problem was the same for all: to live, and not to die,” he says, and he asks the hard question: “Would you have done better?”

During his trial in 2009, the entire court visited S21 itself, and Duch, who converted to Christianity in the years between the fall of the regime and his arrest, is said to have broken down in tears and begged for forgiveness, knowing that there could be no forgiveness. Nothing of this sort happens in Panh’s film. Duch seems sad, sometimes troubled; at moments he laughs nervously, showing stained, crooked teeth, but this seems to be more over the poor hand that life has dealt him than over the deaths of his victims. He searches for a mostly exculpatory middle ground. “In the past, I thought I was innocent,” he says at one point. “Now I don’t think that anymore. I was the regime’s hostage and the perpetrator of this crime.” Panh’s response to this is to note that “all torturers and executioners say they were terrorized. Maybe it’s partially true. The torturer may feel fear, but he has a choice. The prisoner has only fear.”

Panh takes Duch’s lack of moral introspection personally. He yearns in vain for Duch to recognize his mistakes “in detail” and thereby to regain some of the humanity that he’d lost, and this is understandable in a man who suffered as much and as personally as Panh did. But his book leaves out a great deal about the Cambodian tragedy, mentioning only in brief phrases the events that preceded the Khmer Rouge takeover, like the Lon Nol coup and the American bombing campaign. Nor does he deal with the international recognition and support given the Khmer Rouge regime long after the facts of the genocide became known, especially by China and the United States. Both nations wanted to use the murderous regime to counterbalance the victorious North Vietnamese.

The Elimination consists of fragments of memory, of terse, succinct reflections on evil, as well as on obedience to authority, terror, and indoctrination. The memories that float back to Panh recall the Stalin purges and Mao’s Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution in particular. The Angkar dictators brought what they believed was the Marxist class struggle to a point of nonsensical thoroughness in which they wanted not only to eliminate entire classes but also any person who embodied the supposedly corrupt, unequal, and individualistic ways and customs of the previous society. Panh remembers a song on the official radio: “You eat roots,” went the lyrics. “You get malaria; you sleep in the rain; and all the same, you fight for the revolution.”

How did the regime get so many people to do its evil bidding? In a sense, the Khmer Rouge illustrated the tendency of revolutions to destroy forces of moderation in favor of a kind of purifying inhumanity. But even during Mao’s most radical and destructive campaigns, there was no attempt to empty the cities of their millions of inhabitants or to eradicate people who wore glasses. The Khmer Rouge seem to have wanted to go Mao one better, to avoid the mistake of not entirely destroying the class enemy, whose members should no longer be regarded as human, and therefore to have any feeling at all for them was itself a threat to the revolution.

Panh expresses this in one of his reflections:

The work in S-21 consisted of killing after having obtained confessions. That was the work and the rule. If you respected the rule, you killed. If you didn’t kill, they killed you…. That paradoxical legalism, that mixture of power and terror, was devastating.

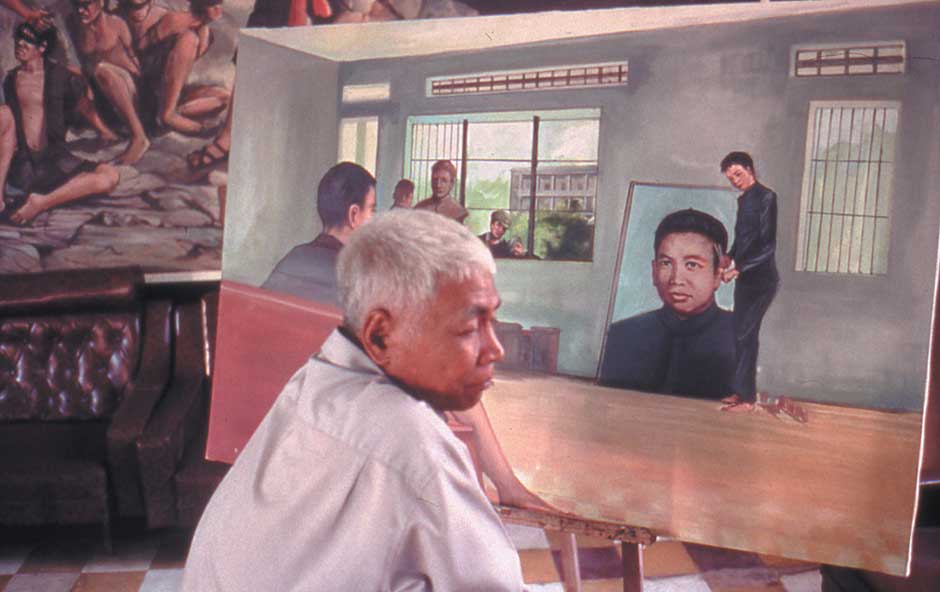

The Angkar had contempt for Duch, who strove nervously and desperately to please it, and Duch in turn passed that contempt on to the prisoners put under his charge. When he ordered some of them to be killed, his instruction was “grind them into dust,” a choice of words that contradicts his claim that he had no choice and that anybody in his place would have done the same thing. One rare survivor of S21 appears both in Panh’s film S21 and in his book. A distinguished, gray-haired painter named Vann Nath at one point tells the former interrogators that to behave as they did, to take obedience to that extreme, “is the end of human conscience.” The disturbing lesson of Panh’s work is that such an absence of conscience was a source of unchallengeable power for the Angkar.

-

1

For a discussion of The Missing Image, see my article “Cambodia’s Unseen Horrors,” NYRblog, October 8, 2013. ↩

-

2

Duch was convicted of crimes against humanity in 2010 and sentenced to life in prison. In the meantime, one of the four other defendants, Ieng Sary, a co-founder of the Khmer Rouge, has died and another, his wife, Ieng Thirith, was declared by the court unfit to stand trial because of mental deterioration. The trials of the two remaining senior Khmer Rouge leaders, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, have been grinding ahead, though they have been plagued by numerous procedural delays. ↩

-

3

See Christopher Browning, Ordinary Men: Reserve Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (HarperCollins, 1992). ↩

-

4

See the website of the Yale Cambodia Genocide Project for information on the numbers of prisons and much else about Democratic Kampuchea. ↩