In 1991 I agreed to translate from the Italian a book called There Is a Place on Earth: A Woman in Birkenau, by Giuliana Tedeschi. It began:

There is a place on earth that is a vast desolate wilderness, a place populated by shadows of the dead in their multitudes, a place where the living are dead, where only death, hate and pain exist.

Giving almost no personal biography, no political history, no statistics, in short, no relief, Tedeschi recounts her own ten months in Birkenau from day one to liberation, focusing on the devastating labor routines, the endless humiliations, the dread of “selection,” the mutual hatred between members of different national, ethnic, and religious groups, and the daily degradation of body and psyche, particularly the female body and psyche.

Having taken on the translation as an ordinary work project, I soon found it impossible to put in the hours I normally would. How can one concentrate on style and grammatical nicety when telling such things? I recall an anecdote in which a group of young women is ordered to go to the gas chambers; naturally they imagine that this is the end. On arrival, however, each is given a baby carriage to push a few hundred yards from the gas chambers to a recycling dump. As their hands make familiar contact with the baby carriage handles, Tedeschi reflects that the emaciated, desexualized bodies of herself and her companions, most in their late teens and early twenties, will now never be able to bear children, nor is she likely to see her own two children again. As for the babies whose carriages these were, their fate is obvious.

Reduced to tears, I decided that this would be the last Holocaust book I would translate and perhaps the last I would read. Receiving the galleys of In Paradise by Peter Matthiessen, who I know as an excellent nature writer and author of the National Book Award–winning Shadow Country (2008), a novel set in Florida in the early years of the twentieth century, I simply dived straight in. I had no idea a book with such a title would be taking me to Auschwitz.

Not that this is really the first book on the Holocaust I’ve read since Tedeschi’s memoir. The 1990s saw an increasing number of novelists, many with no experience of the period or the place, publishing “Holocaust novels.” At present, the website Goodreads has a list of more than seventy “Best Holocaust Novels.” While the desire of survivors to tell, in memoir or fiction, what they went through makes perfect sense, I have always been a little perplexed by these other narratives. Is a salutary remembering, as defense against repetition, really what they are about? How does the enjoyment we associate with fiction, our pleasure in an author’s ingeniousness, mesh with the vast horror of the Holocaust? Occasionally I overcame skepticism to tackle some of these books—Martin Amis’s Time’s Arrow, Christopher Hope’s Serenity House—but in each case it seemed to me that the literary construct was overwhelmed by the enormity of the fact.

The one novelist I’m aware of who successfully exploits the reader’s knowledge of the Holocaust without being swept away by it is Aharon Appelfeld, whose work I was obliged to read when sitting on a jury for a literary prize. Appelfeld, however, achieves his goals by looking at the lives of victims before and after the experience of the camps, which are barely if ever mentioned. The Immortal Bartfuss, for example, recounts the empty middle age of a Holocaust survivor living in mute and miserable hostility with his wife and daughter; any reassuring notions that the extreme experience of the Holocaust would ennoble those who went through it are implacably dismissed. Hence while immersing us in Bartfuss’s arid life, Appelfeld is actually making us aware of our own assumptions about suffering and survival. In a very real sense, Bartfuss did not survive.

Matthiessen is aware of Appelfeld and intensely aware of the pitfalls involved in approaching the Holocaust. The hero of his book, Clements Olin, an American professor specializing in Holocaust literature by Slavic writers, tends, we hear,

to agree with the many who have stated that fresh insight into the horror of the camps is inconceivable, and interpretation by anyone lacking direct personal experience an impertinence, out of the question.

However this acknowledgment only raises the question more sharply: Why does a writer come to the Holocaust? “‘Bearing witness’?” Olin asks himself. “What more witness could be needed? Vernichtungslager. Extermination camp. The name signified all by itself a mythic barbarism and depravity.”

Elsewhere, mentioning the Holocaust documentaries filmed by the Allied armies on arrival at the camps, Olin talks of the viewer’s “moral duty” to “absorb more punishment.” So is the fascination with Auschwitz a form of masochism, with a payoff in piety and self-esteem? Olin claims to be beyond that. He no longer watches such films; “even horror becomes wearisome,” he tells us, “and by now every adult in the Western world has been exposed to awful images of stacked white corpses and body piles bulldozed into pits….”

Advertisement

Reading the opening pages of In Paradise, we’re not aware that it’s Auschwitz we’re headed for. The year is 1996. Traveling from Massachusetts, Polish-born Professor Olin, fifty-five, arrives at Cracow airport, misses his train for his onward journey, and is befriended in a gloomy café by two young Poles who first take him to visit the town and finally offer to drive him the thirty miles to his destination: Oswiecim. Initially friendly, the conversation between the three grows more and more exasperated, since Olin, who has never visited Poland since being smuggled away as a baby, nevertheless knows far more about Cracow’s history than the two youngsters. In particular, though remarking that he is not Jewish, he knows everything about Polish anti-Semitism:

Were you young people never told, he says, that after the war, when those few returning refugees made their way back home to Poland to reclaim their lives, they were reviled and driven off and sometimes bludgeoned and occasionally, when too persistent, killed? “Nearly two thousand Jews were murdered in this country after the war,” he says. “Didn’t you know that?”

Needless to say they do not know, and equally inevitably this approach hardly endears the older man to the two who are helping him. Aware of his “pedantic hectoring,” Olin begins to have “misgivings as to why he has come here in the first place.” Only at this point are we told that Oswiecim is in fact the Polish name for Auschwitz and Olin’s destination nothing other than the camp itself, where the infamous words Arbeit macht frei are still there in fancy wrought iron over the entrance. Together with 140 “pilgrims” from twelve countries, Olin is to spend a “week of homage, prayer, and silent meditation in memory of this camp’s million and more victims.”

One of the things that has radically changed our experience of reading over the last decade is the ability to check any detail instantly on the Internet. So moments after discovering this, for me, bizarre idea of a meditation retreat in a concentration camp, I was able to read an article in Corriere della Sera about an Auschwitz Christmas meditation sleepover during which the author of the piece was convinced he had smelled burning flesh, and an account of an American woman who attended a retreat similar to that described in Matthiessen’s novel:

It was pitch black inside [the crematorium]. As we focused on the space, we both began to feel more strongly the evil of this terrible place, and the unimaginable suffering that happened there over several years. We discussed whether we were simply projecting onto our experience what we already knew, but both of us felt strongly that our feelings were real.

The question immediately arises: Is this, as Corriere della Sera would have it, “the noble tourism of suffering” or the morbid adventure of “Holocaust voyeurs,” as Olin at one point of In Paradise fears? Matthiessen, we learn from a brief article in The New York Times, has attended three such retreats at Auschwitz and is himself a Zen Buddhist priest. He knows the territory.

On arrival Olin claims he has come to the retreat not primarily to meditate, but to do research on Tadeusz Borowski, another writer who both survived and did not survive the camps. The celebrated author of This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen, Borowski was reunited with his girlfriend, also a camp survivor, after the war, only to commit suicide days after their first child was born. However, it soon becomes plain that this academic project is the merest alibi; there must be deeper reasons for Olin’s visit.

As the participants gather for their first meetings, Olin and others are constantly prodded to describe their motivation by the loudmouthed and offensive Gyorgi Earwig, an “unaffiliated” guest determined to attack any manifestation of piety, any notion of closure or resolution or “healing of the faiths.” Seeing a pair of nuns lighting a candle to Maximilian Kolbe, a Polish priest canonized for reputedly giving his life to save an inmate’s life, Earwig denounces this story as a monstrous Catholic myth designed to cover for a pope who “sat on his holy hands while Jews by the millions were going up in smoke.” When an American woman “in a fur-lined leather coat” confesses how terrible she feels on seeing the Holocaust museum, how much she would like to “do something for those people,” Earwig “rounds on her like a poked badger: ‘Do something, lady?’ he snarls. ‘Like what? Take a Jew to lunch?’”

Advertisement

Of Olin’s “research,” Earwig demands:

You got some new angle on mass murder, maybe, that ain’t been written up yet in maybe ten thousand fucking books?… What are you kibitzers really here for?

When Olin replies that he has come to listen to the “silence,” Earwig is scornful: “Bullshit. You think you’ll hear lost voices, right? Like all the rest of ’em.”

In short, far from being a healing experience, initially the meditation retreat generates nothing but friction. Invited, at evening meetings, to come forward and “bear witness,” tearful Germans find that their desire to unburden themselves of national guilt is met with icy coldness, then an Israeli historian is attacked for having admitted that there is a certain element of Jewish provocation behind anti-Semitism. An American Jew is castigated for drawing a parallel between the camps and an ugly episode of prejudice experienced at high school, while a group of Polish intellectuals is criticized for being unwilling to speak up at all. Palestinian Arabs, Buddhist monks, Anglican clergymen, kibbutz workers, rabbis, Czech revolutionaries—as each expresses his position on the Holocaust, he merely rouses the opposition of those who think otherwise.

Even the survivors present are accused of having survived at the expense of so many others. Some break down in tears. One refuses to speak to the Germans. Another threatens to leave. Presented in lively, all too believable dialogue, these scenes allow Matthiessen to get a broad range of angry opinion on the page without being obliged to declare a position of his own.

In the morning participants meditate in silence on the long platform where prisoners went through their first selection on arrival at the camp. Olin, it turns out, like Matthiessen, is a practiced meditator; he knows how to adjust his posture and regulate his breathing “following traditional yogic practice.” Yet as it turns out, very little is said about the meditation experience. Perhaps because, no sooner seated, people find it hard in this dramatic location to stop their minds from wandering, and almost immediately fall victim to hallucinations:

Breathing mindfully moment after moment, his awareness opens and dissolves into snow light. But out of nowhere, just as he had feared, the platform’s emptiness is filled by a multitude of faceless shapes milling close around him. He feels the vibration of their footfalls.

This brings us to the irony, the conundrum if you like, at the heart of the book, and indeed of any “pilgrimage” to sites of this kind. The practice of meditation has the effect of breaking down the ego; in hours of silence, the mind intensely focused on breath and body in the present moment, there is no place for the narrative chatter that feeds the constant construction of the self. Opinions, ambitions, resentments lose their energy. In the Zen tradition meditators focus on koans, complex questions so far beyond understanding that, unable to find a response, the ego again breaks down.

Auschwitz, the death camps, might be thought of as the ultimate koan; Matthiessen quotes Appelfeld as remarking that in the face of the Holocaust “any utterance, any statement, any ‘answer’ is tiny, meaningless, and occasionally ridiculous.” Of the platform where they meditate one of the retreat’s leaders says: “There’s no space left on that platform for interpretation. It’s just there…. It just is.” The hope is that in accepting this, in silent meditation, “we immerse ourselves and are transformed.”

But the ego dies hard and though the camps may be beyond understanding they are nevertheless a source of intense drama and contention, firing and hardening personal opinion. There is also the temptation to make of the meditative experience itself a dramatic episode in the ego’s ongoing and self-regarding narrative: the story of how I went to the death camps and humbled myself before one of the most horrific facts of history. The retreat thus risks becoming an exaltation rather than a dissolution of the ego. This conflict between the drama of the self and its surrender in the shadow of the Holocaust is Matthiessen’s bold subject.

Although Olin claims he plans to listen to “silence,” no sooner does he start meditating than his mind fastens on the real reason for his journey to Auschwitz. His mother, whom he never knew, lived in this very town. He was an illegitimate child. His father, a Polish army officer, had helped his own parents to leave the country before the war and fled with them, while his pregnant girlfriend was left behind. The baby Olin was smuggled out of the country to join the father. Only in adolescence did he begin to hear rumors, from his snobbish, quietly anti-Semitic paternal grandparents, that his mother may have been part Jewish. Now, albeit with the reluctance of someone anxious that his entire sense of self is about to change, he wants to see if anyone in Oswiecim remembers his mother.

As he begins that quest and as if in reaction to the truth he already suspects he must uncover—that his mother died here in Auschwitz—Olin strikes out rather desperately on another possible change in his life story: he falls in love with the nun who was earlier insulted for lighting the candle in honor of Kolbe. Sister Catherine, it turns out, is actually a novice in her thirties in conflict with the church over various issues, hence someone who just might abandon her vocation for Olin.

If the first half of the novel, then, is mainly ferocious debate, presumably drawn from Matthiessen’s own experience of Auschwitz retreats, the second is a heady, not always convincing intertwining of narratives in which Olin’s reluctance to accept the truth about his mother, his Jewishness, and his personal connection with the camps aligns with the world’s general wish if not to deny then at least quietly to forget about the Holocaust. At the crematorium where he supposes his mother must have died, Olin’s mind is seized and thronged with deeply disturbing images. Later, the rabbi attending the retreat advises those participants who are finding the experience difficult that “the only whole heart is the broken heart. But it must be wholly broken.” At once we know that this must be Olin’s fate.

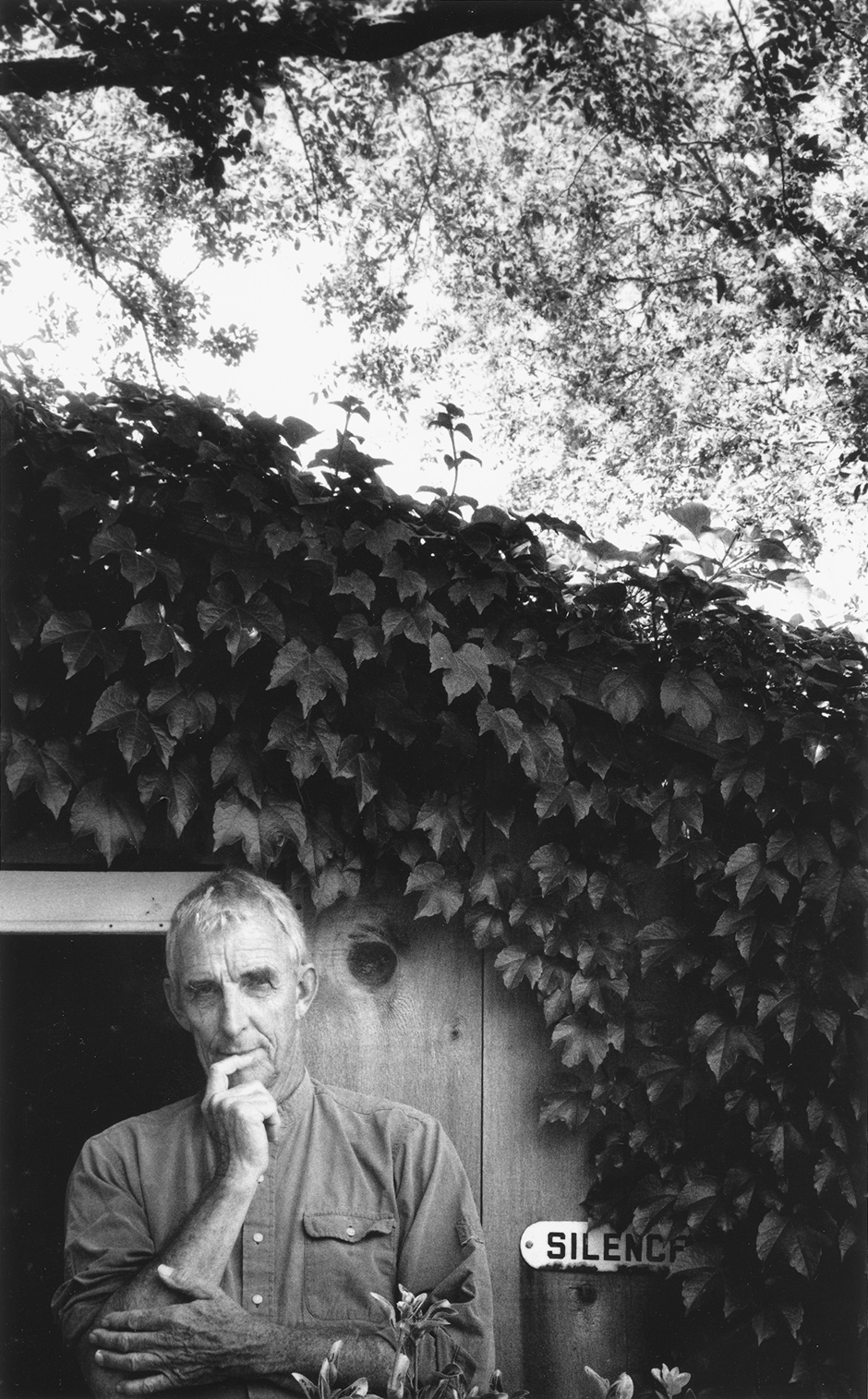

Matthiessen’s work has always carried a powerful moral message. Much of his nature writing, with its uncanny ability to capture landscape and weather, denounces the scandal of man’s destruction of the flora and fauna he so beautifully evokes. His defense, In the Spirit of Crazy Horse (1983), of the imprisoned American Indian Leonard Peltier and the Indian cause in general was entirely in line with this, and likewise Shadow Country is constantly moving us to acknowledge the shameful, unspoken truths that allow the ugly events of the novel’s story to unfold. In this sense, though it may seem a departure, In Paradise is a logical conclusion to a long writing career, for Matthiessen, now in his eighties, has said that this will be his last book.

The Holocaust, the impossibility even today of getting a group of people to shed their selfishness and their differences in the presence of the Holocaust, is perhaps the ultimate indictment of man’s perversity. But in a scene that I imagine Matthiessen must have witnessed himself, since it seems too bizarre to be invented, an oddly positive note is struck. As the rabbi closes an evening meeting singing “Oseh Shalom,” a number of participants join hands and, spontaneously, almost unconsciously, find themselves going about the room in a dance of great transport and intimacy. Olin is as grateful as he is surprised:

What could there be to celebrate in such a place? Who cares? He is delighted to be caught up in it…. He moves with it, into it, and now it is moving him as the bonds of his despair relent like weary sinew and gratitude floods his heart. He feels filled with well-being, blessed, whatever “blessed” might mean to a lifelong non-believer.

It’s hard not to feel that in describing this strange moment of beatitude, Matthiessen is looking for an analogy with his own bleak endeavor to conjure some positive collective spirit from torment and ugliness. Needless to say, no sooner is the dance over than it becomes an object of fierce controversy, denounced by most as sacrilege, praised by some as transcendence. Matthiessen is no doubt aware that his powerful book will likely provoke the same heated disagreement.