You can read Jenny Offill’s new novel in about two hours. It’s short and funny and absorbing, an effortless-seeming downhill ride that picks up astonishing narrative speed as it goes. What’s remarkable is that Offill achieves this effect using what you might call an experimental or avant-garde style of narration, one that we associate with difficulty and disorientation rather than speed and easy pleasure. The novel tells the story of a marital crisis in the lives of a previously more-or-less happy couple. Short microepisodes from the lives of the couple alternate with facts and quotations from all kinds of sources—scientific studies, foreign proverbs, the poems of John Berryman, the writing of Simone Weil, to take a few examples.

Here, in its entirety, is a chapter from near the beginning of the book. The narrator is recalling a period of her life when she was in her late twenties and early thirties. She has recently published her first novel. She has had various boyfriends but is now single and lives alone in New York:

There is a man who travels around the world trying to find places where you can stand still and hear no human sound. It is impossible to feel calm in cities, he believes, because we so rarely hear birdsong there. Our ears evolved to be our warning systems. We are on high alert in places where no birds sing. To live in a city is to be forever flinching.

The Buddhists say there are 121 states of consciousness. Of these, only three involve misery or suffering. Most of us spend our time moving back and forth between these three.

Blue jays spend every Friday with the devil, the old lady at the park told me.

“You need to get out of that stupid city,” my sister said. “Get some fresh air.” Four years ago, she and her husband left [the city]. They moved to Pennsylvania to an old ramshackle house on the Delaware River. Last spring, she came to visit me with her kids. We went to the park; we went to the zoo; we went to the planetarium. But still they hated it. Why is everyone yelling here?

The philosopher’s apartment was the most peaceful place I knew. It had good light and looked out over the water. We spent our Sundays there eating pancakes and eggs. He was adjuncting now and doing late nights at the radio station. “You should meet this guy I work with. He makes soundscapes of the city.” I looked at the pigeons outside his window. “What does that even mean?” I said.

He gave me a CD to take home. On the cover was an old yellow phone book, ruined by rain. I closed my eyes and listened to it. Who is this person? I wondered.

In six short paragraphs: the lonely urban grind; years spent slogging through a city that has lost whatever magic it once had for her; our introduction to the narrator’s sister and her best friend (a philosophy professor), both of whom will play important parts in the crisis; and the lead-up to the meeting with the soundscapes guy, the man who will become her husband.

You would think that a chain of fragments—however engrossing those fragments are—could only slow down a reader. Think of how long it takes to read a page of short paragraphs in David Markson’s late novels. Offill’s style has some kinship with Markson’s, but her novel is straightforwardly a work of realism, with characters and plot. She not only assembles her passages into a surprisingly fluid narrative, but uses her interpolated material to make the story move faster than conventional narration. She proceeds by analogy.

The first half of the novel describes a kind of idyll. The narrator and the soundscapes guy start seeing each other. She likes him. She goes abroad for some period of time, perhaps on a fellowship, and he comes to visit her:

But it was late when we spotted each other at the train station. You had a ten-dollar haircut. I was fatter than when I’d left. It seemed possible that we’d traveled across the world in error. We tried to reserve judgment.

They survive that first little disillusionment. They stay together. When she had been younger, the narrator used to keep a sign saying “WORK NOT LOVE!” above her desk (“it seemed a sturdier kind of happiness”). She was going to be a writer, “an art monster,” someone devoted to her work above all.

But love it seems to be, with the soundscapes guy. He proposes, they marry, they have a baby. They set up in a small Brooklyn apartment. Her husband, a sound engineer, gets a new, less interesting, but steadier job scoring music for commercials. She teaches creative writing at a college and scrambles to meet the requirements for tenure. (“‘Where is that second novel?’ the head of my department asks me. ‘Tick tock. Tick tock.’”) They run low on money and she takes another job ghostwriting a book about the history of the space program. They discover that they have bedbugs and have to boil all their clothes.

Advertisement

At this point, seven or eight or nine years into their married life, we start seeing references to tiny, isolated space capsules and ill-fated polar expeditions. Offill quotes an 1898 entry from the log of the explorer Frederick Cook, “trapped with his men on an icebound ship” off Antarctica:

We are as tired of each other’s company as we are of the cold monotony of the black night and of the unpalatable sameness of our food. Physically, mentally, and perhaps morally, then, we are depressed, and from my past experience… I know that this depression will increase.

Other critics have likened Dept. of Speculation to Renata Adler’s novels Speedboat and Pitch Dark, which are also written in patterned, episodic fragments. The comparison is interesting for differences as well as similarities. Speedboat’s narrator Jen Fain, a journalist, observes the urban spectacles that unfold before her; she records not only episodes from her own life but news and gossip from the social worlds she travels in, conversations overheard between strangers, scenes witnessed in different corners of New York City. Like the persona of Joan Didion’s essays and reportage of the late 1960s and 1970s, Jen Fain is cool. Her deadpan or skeptical, emotionally withholding tone evokes shock after a rupture—she can’t quite orient herself to the way people, including herself, think and live. “Things have changed very much, several times, since I grew up,” Fain memorably tells us.

Offill’s narrator has a different way of registering her place in the world. She does not style herself an observer of her times. If things have changed very much since she grew up, we don’t hear about it. The novel is closely trained on what we call the personal life—her marriage, her daughter, her work. She occasionally reports on things other mothers say at the playground. One mother presents to the others what our narrator ironically calls a “dilemma”:

They have finally found a house, a brownstone with four floors and a garden, perfectly maintained on the loveliest of blocks in the least anxiety producing of school districts, but now she finds that she spends much of her day on one floor looking for something that has actually been left on another floor.

Read one way, this is an obnoxious rich person’s complaint, ripe for satire. Or, if told with the proper self-awareness and social awareness, it could be a funny joke at the teller’s expense. What it can’t be is a story told straight. We doubt—our narrator cues us to doubt, and it is part of the national mood to doubt—that the woman in the brownstone has any claim to our sympathetic interest. She may not have a good life, but she is rich; her dilemmas are to be solved privately, not dramatized.

Offill’s narrator is not brownstone-rich; nor is she beset with the kind of ennui that might be suggested by the story of a woman who spends all day looking for misplaced objects. Offill’s narrator has much that she wants to do in her life—particularly to write her next novel—and not enough time to do it, for she has a child and two day jobs. But if we pull back, we could say that Offill’s narrator has most of the things she wants, she just can’t have exactly the thing she wants at exactly the time she wants it. Will she be mistaken for the woman in the brownstone?

The narrator’s anxieties, when not about the immediate matters of her life, tend toward the global- or galactic-scale disaster. Climate change is mentioned in this novel, but not wars, elections, gentrification, or the Dow. Minding her daughter one day, she half-listens to a scientist on television talking about some potential cosmic disaster whose explanation she missed, something to do with “ruinous movements” of “the heavens”:

The time lapse shows a field of plants perishing, a mother and child blown away by a wave of red light. Something distant and imperfectly understood is to blame for this. But the odds against it are encouraging. Astronomical even.

Still, I won’t be happy until I know the name of this thing.

The novel has many such moments of telescoping between the domestic and cosmic. Our narrator once lived in a sub-ground-floor apartment whose windows were at the level of the sidewalk. One morning, “as I lay in bed, a bright red sun appeared in the window. It bounced from side to side, then became a ball.” Later, her daughter learns the word “ball” and “can spot a ball-shaped object at one hundred paces. Ball, she calls the moon. Ball. Ball.”

Advertisement

These small misunderstandings of scale, the characters’ momentary confusions of the mundane with the cosmic, are not insignificant with respect to the larger subject of the novel. This is a novel about marriage and adultery. It has become a commonplace that adultery is a low-stakes subject for a contemporary novel set in a sexually egalitarian, divorce-friendly American society where most people marry with a fair amount of sexual and romantic experience. A contemporary case of adultery seems like a small story, and any attempt to enlarge it risks an unintentionally comical misunderstanding of scale.

“Put romantic love at the center of a novel today, and who could be persuaded that in its pursuit the characters are going to get to something large?” wrote Vivian Gornick in the title essay of her 1997 collection, The End of the Novel of Love. “Adultery has withered as a fictional theme because it drags such little consequence behind it nowadays,” wrote James Wood in a review of Monica Ali’s novel Brick Lane (2003) in The New Republic. “Sexual equality, good for women, had been bad for the novel. And divorce had undone it completely” is how fictional college student Madeleine Hanna summarizes the views of her English professor in Jeffrey Eugenides’s novel The Marriage Plot (2011). The line is a winking reference to Eugenides’s own ambitions in writing about love and marriage; a novelist can still write about those subjects, but—Eugenides reminds his readers—they can’t be draped with the kinds of meanings they might once have had. Today the novel of marriage asks, Why marry?

About halfway through Dept. of Speculation, something happens. It’s not immediately clear what, but for one thing, the narration is no longer in the first person but the third. Instead of an “I” and a “my husband,” there is “the wife” and “the husband.” The switch to third person suggests that the characters have been overtaken by their marital roles. It also evokes a kind of dissociation, perhaps brought on by a crisis.

The crisis slowly comes into focus. A month after she sort of notices something strange in his facial expression, the wife asks the husband whether he’s having an affair. He answers evasively. She is unsettled. What is it like to be jolted into jealousy and suspicion of your husband when previously it would never even have occurred to you that there could be anything to be suspicious about? It’s the sort of surprise that focuses your attention, and might lead you to acts of obsessive scrutiny. Offill refers us to an episode from the life of the great astronomer of antiquity:

In the year 134 B.C., Hipparchus observed a new star. Until that moment he had believed steadfastly in the permanence of them. He then set out to catalog all the principal stars so as to know if any others appeared or disappeared.

Some amount of time passes, the husband comes home suspiciously late, the wife asks again about an affair, and he again dodges the question. Another night passes and she asks again, and this time he confirms it. Now we pick up speed again. The wife’s sister comes to take their daughter on a day trip so that the wife and husband can fight in their apartment. The wife of course has many questions about the other woman.

Taller?

Thinner?

Quieter?

Easier, he says.

There seems to be no question that the affair is serious. The husband shocks the wife by using the word “us” to refer to himself and the other woman. The wife staggers through her old routines, “invents allergies to explain her red eyes and migraines to explain the blinked-back look of pain.” Offill doesn’t actually use the word “affair” until several chapters later, and attributes it to a corny self-help book. By this time they’ve told their friends, started going to couples therapy, and are considering a separation:

The wife is advised to read a horribly titled adultery book. She takes the subway three neighborhoods away to buy it. The whole experience of reading it makes her feel compromised, and she hides it around the house with the fervor another might use to hide a gun or a kilo of heroin. In the book, he is referred to as the participating partner and she as the hurt one. There are many other icky things, but there is one thing in the book that makes her laugh out loud. It is in a footnote about the way different cultures handle repairing a marriage after an affair.

In America, the participating partner is likely to spend an average of 1,000 hours processing the incident with the hurt partner. This cannot be rushed.

When she reads this, the wife feels very very sorry for the husband.

Who is only about 515 hours in.

How did the affair unfold without the wife’s knowing, in such a close marriage set in such close quarters? The wife’s friends are skeptical. “People say, You must have known. How could you not know? To which she says, Nothing has ever surprised me more in my life.” There are of course other kinds of personal calamities that inevitably come as a surprise regardless of how often we hear about them. Illness, injury, death. Interesting that adultery should keep company with these dire fates.

At the edges of the novel, Offill allows for the fact that it is possible to have other kinds of arrangements regarding affairs, to make a greater mental provision for the event that has so painfully blindsided the narrator. It turns out that the narrator’s own sister has “a deal with her husband: Whatever happens, keep it like in the fifties. Not one word ever. Make sure she’s a nobody.” But the narrator did not have an arrangement like this. She is more like the other wives she meets on the playground, whom she judges harshly but whose sexual requirements of their husbands are, on close inspection, no different from her own: “Unswerving obedience. Loyalty unto death.”

Perhaps the interesting point here is not the wisdom or practicality of the demands themselves but the fact that it’s the wives who are making them. In the canon of adultery novels, there are more stories about the adulterous partner than about the wronged spouse. Where he does get his own book, the wronged spouse is usually a man, as in The Good Soldier, A Handful of Dust, Herzog, Jealousy. In the history of the novel, female adulterous desire has been a major force, female jealousy a minor one.

Before any of this trouble happened, the narrator recalls, her literary agent had told her her theory that “every marriage is jerry-rigged. Even the ones that look reasonable from the outside are held together inside with chewing gum and wire and string.” As opposed to what? one wonders. What would a marriage of poured concrete look like? Or is the implicit comparison not to masonry but to magic? Perhaps the problem with chewing gum and wire is not that they are flimsy, but that they are unenchanted, man-made materials.

Offill’s wife and husband have, or at least once had, between them all the elements one is supposed to hope for—love and desire and friendship and their adored daughter. How can a relationship so intensely intimate and companionable seem so easily soluble? And what is that other thing, extramarital sex, that has everyone so quickly making contingency plans to jump ship? The wife and husband’s exemplary, perhaps even ideal, modern marriage is a form of personal gratification—a nonbinding choice that is very much bound up with the ego.

No wonder the narrator’s howl of pain: the marriage, at that moment of revelation, for all practical purposes, is the self. And it is one’s sense of self that is held together with chewing gum and string; marriage is a part of the jerry-rigging that might, with some luck, temporarily give a person the feeling that she is not a needy, grasping, emotionally unstable wreck. This is the true idyll offered by marriage. But this blissful interlude, which does not feel like bliss but only like ordinary life, can come to an end.

You might say that a revelation of adultery, shorn of its old consequences, is the smallest possible disaster that still registers on the personal disaster scale. As such, it is formally comical, and a novelist must recognize the comedy. If she also wants to take her characters’ experience seriously, rather than reduce it to satire, she has to perform a delicate balancing act. Here is Offill’s heroine considering her troubles:

No one gets the crack-up he expects. The wife was planning for the one with the headscarf and the dark jokes and the people speaking kindly at her funeral.

Oh wait, might still get that one.

The wife has had to learn a difficult lesson about the impermanence of human arrangements, but she has been allowed to learn it in the gentlest possible way.

This Issue

April 24, 2014

The Mental Life of Plants and Worms

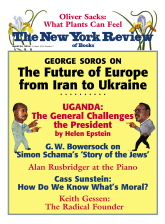

The Future of Europe