Falls, North Carolina, the setting for the three long stories or novellas that make up Allan Gurganus’s Local Souls, is the kind of place where people end up, come back to, can’t get away from. It has descendants of Confederates who consider themselves aristocrats, new tobacco money that has got old, middle-class, divorced white women stretching child support payments, white professionals, black tobacco workers, and black caddies at the country club, although this microcosm of a new New South has no Latinos. Falls is a farm town, though it has a slum. Falls also has the rural white poor who never dreamed they’d end up living among “the Fallen,” the rich who had their great houses on the River Road until the River Lithium answered the call of global warming and overflowed its banks.

Falls is not Yoknapatawpha County, but it has a history, its own obsession with the Civil War and with being southern, beginning in Gurganus’s exuberant first novel, Oldest Confederate Widow Tells All (1989). Falls mostly wears its post–World War II face in Gurganus’s work, which sometimes blurs the line between fiction and memoir. Falls is his childhood landscape. The writer is the narrator of “He’s One, Too,” a story from The Practical Heart (2001) that recounts the destruction of a married man and his family after he’s arrested for approaching a youth in a urinal in Falls in 1957. In one of the stories in Gurganus’s collection White People (1990), a sweet but lonely fan of pornography is living in his mother’s big house in Falls, with a long-out-of-date 1959 calendar still on the wall. In his second novel, Plays Well with Others (1997), Gurganus’s narrator is a writer, safely back in Falls, having survived the madness of New York and AIDS in the early 1980s.

In the stories of Gurganus, the South is a small town, whether a street in Richmond or Charlottesville or Falls. It is the home of secrets, of things not being what they seem. Proximity is scrutiny; neighbors are stories. What the small town means maybe hasn’t changed since Sherwood Anderson’s time. If it is not the social truth anymore, then the small town is a powerful literary convention nevertheless. We accept that the small town can reveal something essential about the American soul, northern or southern.

The fortunate are still available for satire; they are also tough enough to survive being the targets of Gurganus-style black comedy. The first novella of Local Souls, “Fear Not,” introduces a writer attending a Falls High School production of Sweeney Todd. He is anxious to hear from his New York agent about the Civil War novel he has just handed in. It took him seven years to write it. He is restless, curious, wary of empty time. “Aren’t all real writers always writing?” he asks. A handsome blond couple in the audience attracts his attention. He can’t help but make up a story about them to explain the extraordinary appeal and effect of their obvious deep affection for each other. The woman is somewhat older than the man. A friend tells the writer what she knows of their story. “A storyteller’s first task is knowing the tale when he sees it,” the writer says. “Easy when one’s this human.” His dogged research turns up the rest.

One July 4 at Moonlight Lake, three miles from Falls, a Pleasure-Craft outboard decapitates the water skier who has been riding behind. The captain and the skier were the closest of friends. The dead man’s wife and fourteen-year-old daughter had been sunning on the beach at the time of the accident. They can’t cope with such a good man’s death. The town understands that his best friend, a respected physician, grieves in the company of the dead man’s daughter. However, Susan, as we find out much later she’s called, turns up pregnant by her father’s inconsolable friend, her godfather.

We’re told that her mother made a scene when he attended the local Episcopal church. The guilty doctor moved with his family to Maine, where he tried to commit suicide but was saved. In time, he earned the good opinion of the place where he settled and practiced part-time. Gurganus follows the innocent daughter from a home for unwed mothers and the loss of her baby to an orphanage, through high school, college, marriage to a young medical student, and the birth of two daughters. She lives in Atlanta, goes to graduate school for Russian literature, and leads a book discussion group among doctors’ wives, but her feeling for Chekhov far outstrips anyone else’s:

Given her unsettled girlhood, the Russians’ sense of Fate had spoken to her early. She’d been assigned a decapitated father, an unsought pregnancy courtesy of her dad’s killer; eventfulness in fiction did not embarrass her. Fate no longer seemed the design concept making Novels of Coincidence easier to write. Fate felt—like tidal waves or hurricanes—an inexorable, arbitrary natural force. (If she had ceased at age fourteen to believe in Luck, she now accepted Fate as Luck’s adult-content replacement.)

The Internet arrives; she hits a firewall when making inquiries about her firstborn’s orphanage. But imagining her lost child helps her to settle into her life, even if it is composed of what she thinks of as dry hours. Then one day her nineteen-year-old son tracks her down, using Internet skills she doesn’t have, and he turns up at her door: “Luck must weigh a hundred and seventy pounds, easy.”

Advertisement

Their reunion is very physical and to judge by what residents of Falls consider scandalous about them their relationship has remained intense: “Same events that overwhelm Greek dramas live on side streets paying taxes in our smallest towns.” She’s shed the husband, who surrendered custody of his two daughters. There is some suggestion that the daughters don’t know who the boy really is. “You say you’re always interested in whatever brings people back to Falls,” the writer’s friend says. “Maybe people do return to scenes of crimes, especially crimes against them.”

In “Saints Have Mothers,” a mother finds her identity when she learns that she has lost her child. Jean, the mother, takes a wry tone toward her activist daughter, Caitlin. Her resentment of her daughter is partly generational: the life of a girl in her daughter’s time is so much more free and full of possibilities than it had been for women her age. Then, too, as proud of her socially innocent and intellectually precocious daughter as Jean was, she finds that a principled, willful child also could be tedious. As a little girl, Caitlin used to give away Jean’s shoes to the homeless. Somebody else always pays for the gestures of the politically committed star in the family. Jean is also the mother of twin boys and divorced. To be a single parent put limitations on her life, but she seems to have felt her missed chances most keenly when faced with the accomplishments of her daughter.

Caitlin “deficit-spent her spirit all across tiny Falls, NC,” and Jean begged her “not to overgive to immense summertime Africa.” But her daughter wanted to rush off during her last summer before college to “impress another continent.” Caitlin isn’t just an exceptional student and “scarily pretty,” an achiever welcome in every school clique. She has had since she was a toddler a highly evolved capacity for empathy and goes to Simone Weil–like lengths to make real in her own life the moral presence of the suffering. And yet she is not entirely likable. You can get fed up with reckless courage.

Jean receives a call from Africa, telling her that her daughter has drowned and she must make arrangements for the body. Caitlin’s friends rush to console her. “Filled with student body officers, my home soon felt like the Hollywood Canteen.” The outpouring of love frees her to take pride again in her daughter, who becomes a national news story, a heroine. The emotion and attention reawaken Jean. She is drawn into her daughter’s world; to her the boys are as beautiful as deer. She throws herself into the planning of her daughter’s memorial. She joins the “Cult of Caitlin.” Her own gifts get tapped again. Meanwhile, a mood develops between her and her daughter’s music teacher, who may finally realize his potential through the composition of a piece in memory of his glorious student.

But the day her body is due to arrive, in the middle of the World Cup, Caitlin returns, unharmed. She’d gone off radar in the jungle, so to speak, as a way of silencing her mother’s criticism of her for doing dangerous work. Jean has been the victim of a scam by which distraught parents are hustled into sending money in order to retrieve their child’s body from some remote place. After the relief and gratitude, the tears, Jean is angry, once again merely the mother of a “somebody.” “I felt ashamed everywhere I went in Falls,” she says. Mother and daughter bicker daily. The daughter involves her father, Jean’s ex-husband, in what she considers her mother’s deterioration, her reaction to the stress of the summer. They pack Jean off to a seminar on Elizabeth Bishop. She is telling us her story from the ferry en route to an “Ocracoke Island B & B.”

Falls, North Carolina, then—and the three novellas also have in common their larger subject, the parent–child bond. Yet these first-person tales are somewhat queasy-making in that they are tales of deformed love, a sort of Gurganus specialty. “Subversive” is an empty compliment in critical language these days, and the southern history that Gurganus is steeped in isn’t subversive just because it is about this region that has its historical defeat as its identity still. But these new stories are somehow transgressive in feeling, perhaps because in them someone is asking for something she ought not to; someone is admitting to impulses we would rather not have considered. The scandal of incestuous intensity floats around these pages, baroque sexual imaginings being a specialty of the southern town in American literature, a narrative tradition that assumes everything will get found out.

Advertisement

In “Decoy,” Bill Mabry, morbidly self-conscious, farm-born, with a weak heart he inherited from his father, tells himself:

Falls’ 6,803 souls felt known for generations by both first-and-last names. Our homes, remodeled, look even better to us. Not quite a heaven? but surely zoned to banish eyesore hell. And folks that left at age eighteen—even ones now well-known artists in New York—you think they’re a bit happier?

Those of us who stuck by Falls, we sometimes fear we’ve fallen off the big-time honor-roll. And yet, our town—if on certain days a letdown—landed intact, nicely right-side-up beside the still waters. Till right here lately, we who stayed, stayed mostly cozy.

Bill’s tale of unrequited love is one of abject patience, of waiting his whole life to be noticed, to have an exchange with the beloved that feels reciprocal. “The man gave us admitted sinners insufficient human traction,” he says. In the meantime, Bill has a social acceptance among the upper-crust people of Falls that his father, who couldn’t play golf well enough, never knew. He’s an insurance salesman, a father of two successful children, a grandfather married to a wife he gets along with. He has come so far from where his father started that he can regret the dot-com money that has come to his genteel part of the world. Still, he’s not entirely sure he doesn’t look more “rural Baptist” than “chess-playing Episcopalian.” His father escaped sharecropping by becoming a contractor. An eccentric client left him a considerable sum and his Falls country club membership in his will. “Your ticket to the middle class is, once punched, irrevocable,” Bill muses.

Doc Roper, a well-born son of Falls, was twenty-nine, Bill nineteen, when Roper took him and his father on as patients. “Then, slower, Roper took us up as friends. He was the first to understand, then explain, what-all was wrong with us.” But after forty years, Bill does not understand the man he so admires, starting with why a good-looking Yale man would come back to Falls to practice. Bill explains that he has always been inclined to hero-worship, just as Falls is the kind of place that makes a big deal of the internalist-generalist physician into whose hands they have placed themselves. Roper is especially gifted as a diagnostician. His retirement is something of a traumatic event for his patient-dependents. They feel jilted by him. Bill owes him his life, believes that Roper has kept him alive past the age his father was when he died.

But there is something off about Bill’s concentration on the impenetrability and aloofness of the doctor whose town he has shared all his life. We sort of expect some visit to the doctor’s examination table to turn sexual, awkward, but it never does. The doctor has always looked out for him and in return Bill has only had his “goodwill” to offer, and that it has gone unacknowledged or unrecognized during their long association is perhaps what drives him to try to connect with the man their class of townspeople find so intimidating. “Why had I, the man seen best from afar if at all,” he asks, “chosen as my closest friend the best-loved man in town?” Bill is humiliated when Dr. Roper prefers to sell his best wood-carved duck decoy—the all-consuming interest of his new leisure—to someone in New York rather than to him.

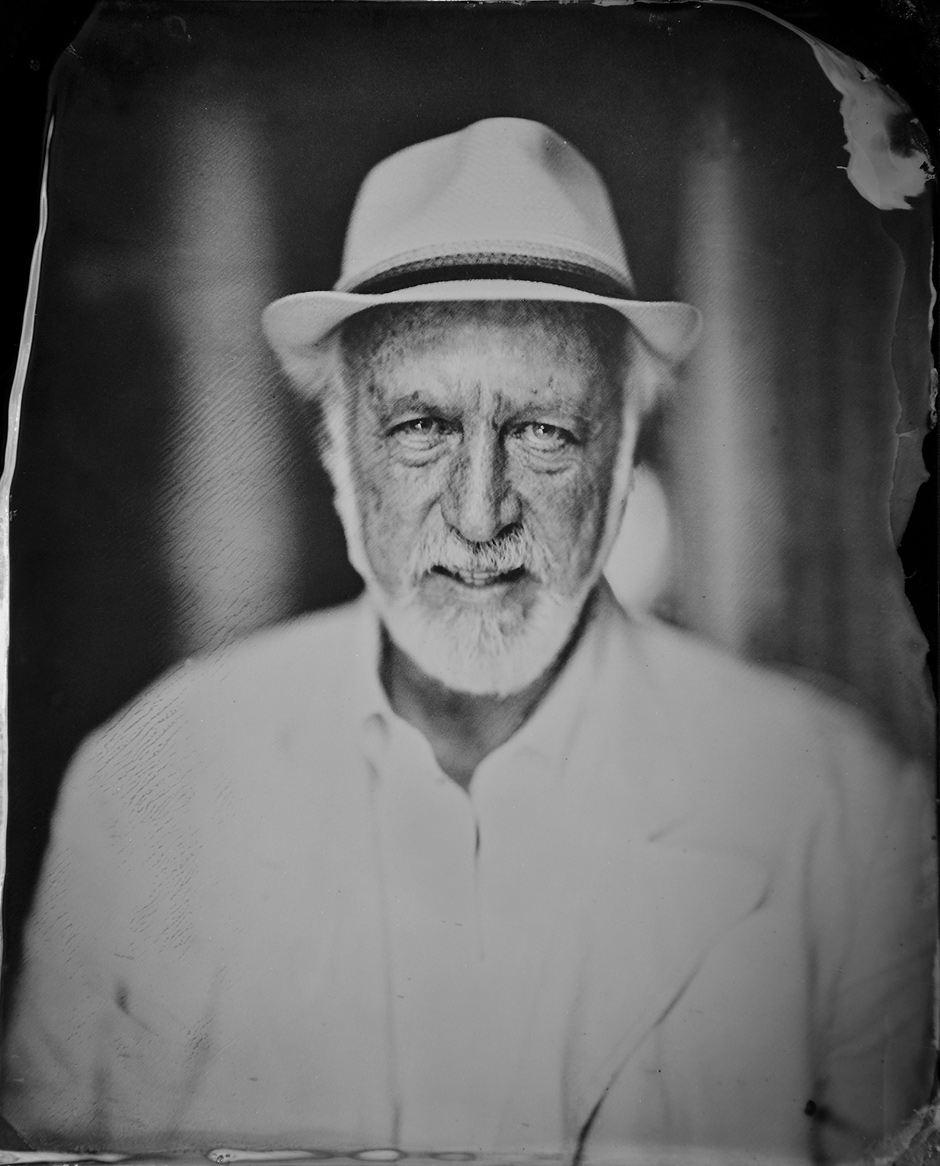

In Gurganus’s emotionally dense fictions, his small towns are not isolated from the rest of the world. Bill Mabry reads The New York Review in the Falls library. Gurganus moves by moments, by degrees of perception, of admitted information, and his language can intensify accordingly, making the light on what he’s looking at get brighter, putting the rest of the picture into shadow. He excels at depicting the individual character at his or her most vulnerable, even pathetic, alone with his or her consciousness, full of guilty thoughts. Certain characters or passages from Gurganus’s stories stay in the mind: simple moments, like an adolescent’s shame that he has destroyed his little brother’s collection of models, because of his hurt that his brother is accepted by the boys who bully him.

After a hurricane passes through Falls, Bill has a tantrum about Roper right in the middle of the gym where he and the other flood victims from the River Road have taken shelter. “Why will we forgive him anything?” Bill’s obscure rage is relieved when he remembers that Doc’s wood-carving studio is ruined:

It’s counterproductive, living in a town so small. Limits your escaping unobserved. More new charismatic churches, while car dealerships keep closing, and no Harley-Davidson outlet for the Fallen. So small a place when one has hopes so Roper-huge. And, what did I want for him and myself? That…that’s on the tip of my tongue. It’s just, to me, the two of us always seemed secretly made of finer stuff. Alike in being different. But what chance did we have, in a zone so rural, strict and married?

Though Gurganus has a great sense of place, realism isn’t exactly what he’s about. “Life can retract its promise overnight,” Bill says in “Decoy,” “even in a moneyed river town.” Experience isn’t turned into stories, it becomes the process of storytelling. In Oldest Confederate Widow Tells All, Lucy Marsden sits up in her nursing home bed in 1938 and starts dictating to a reporter her memories of her husband, who had been at Appomattox. She calls forth other witnesses in this long, ranging work, even stepping aside to give a freedwoman her moment on stage.

Ever since that book, you could say that the literary point of Gurganus’s work would be in the pleasures of the first-person voice. He is inventive in its uses, going after the colloquial, not afraid to ramble if that is a necessary aspect of the personality of a particular voice. He differentiates among his narrators, tries to find for each his or her proper register.

In Local Souls, he writes of a tormented group unable to cope with the past or to project a coherent future. A part of that must be in Gurganus’s generational allegiances. Technological change is an uneasy factor in these lives. It coincides with the further fracturing of narrative. “Are novels even valid this late in human history?” Caitlin, the teenage saint, asks herself. His fiction now seems to be saying that the form is malleable these days, gliding between the real and the many other narrative choices out there. We would expect the electronic age, the vastness of it, to make the question of form even more open-ended. However, because of the Internet, for instance, as he suggests in “Fear Not,” the past just turning up is even more likely. Therefore old-fashioned fictional devices, those we associate with, say, The Mayor of Casterbridge, are more believable in the nanotechnology age, not less so.

We accept self-conscious, provisional, indeterminate qualities as true to the flux of consciousness, when all around is uncertain; and the language may be changing under the pressure of the abbreviated codes of electronic communication. By contrast, Gurganus’s storytellers are defiantly committed to telling us the big stuff. They don’t look into the nets of the everyday. But his first-person speakers don’t sound as southern as they used to. Maybe this kind of regionalism is going; maybe that kind of southern drawl has lost plausibility or appeal as a representation of class.