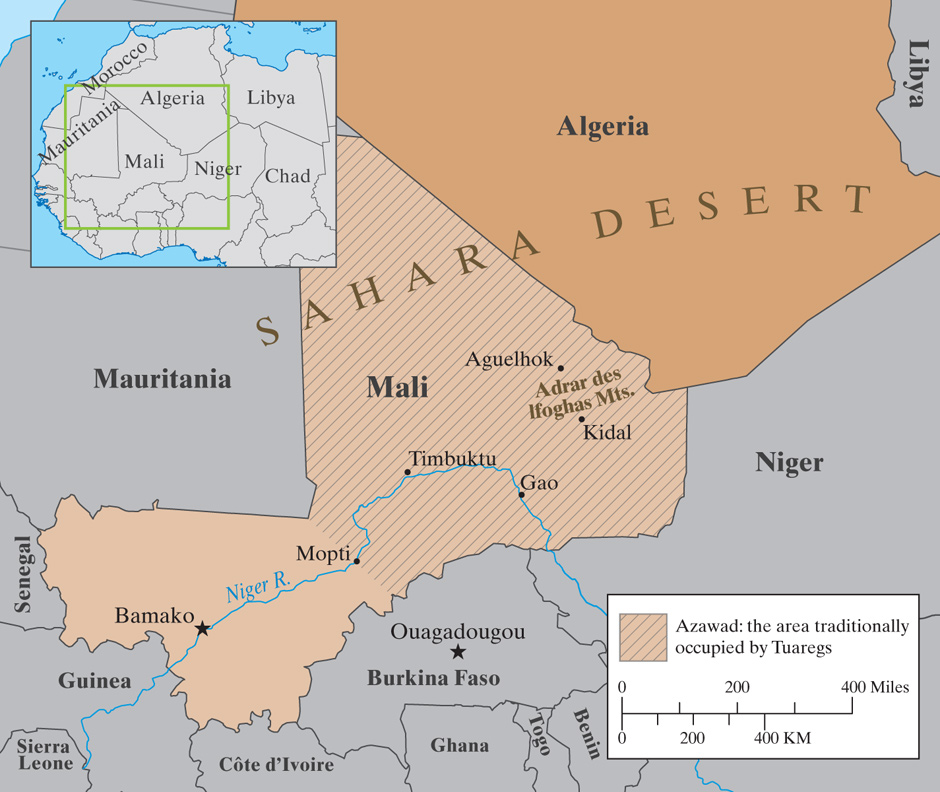

In 2012 Mali descended into chaos. Much of the north of this large and very poor country of 16 million people—its area about the size of France and Spain put together—was taken over by a shaky alliance between hard-line Islamists and Berber Tuaregs, some of whom had come from post-Qaddafi Libya, some from their traditional home in northern Mali. At the same time, the government in the capital city of Bamako was deposed in a military coup led by Amadou Sanogo, a midlevel military official. In January 2013 some four thousand French troops joined the Malian army in an offensive that drove out the Islamists and Tuareg fighters and restored control of much of the north to the government. Fighting still continues, and a residual French force remains in Mali alongside a smaller contingent of German troops and a sizable African force.

Visiting Mali in February, I flew in a United Nations–chartered Antonov jet from Bamako to Kidal, a sand-blown regional capital of 30,000 people, tucked into the northeastern corner of the country (see the map below). The plane was packed with civilian engineers, French officers, and contingents of soldiers and police from Senegal, Guinea, and Burkina Faso. Almost everyone got off in the towns of Mopti and Gao, and I was nearly alone on the plane when it finally touched down at Kidal. I was the first journalist to visit the outpost since al-Qaeda in the Islamic Magreb, the North African affiliate of the international terrorist organization, kidnapped and murdered two French correspondents there last November. The UN civilian staff members who arranged my trip told me that the place was so dangerous that I could stay on the ground for only twenty-four hours, and would not be able to leave the UN compound except in an armored vehicle, with an escort of blue helmets for protection.

Stepping off the plane into the blinding sunlight, I watched UN peacekeepers in turbans roar up in six camouflage-painted pickup trucks with heavy machine guns, protecting the plane from attack. A hot wind was blowing, sending up sprays of sand. In the distance, I could see the Adrar des Ifoghas, a long line of black mountains rising above a sea of scrub. “The terrorists are still there,” a French colonel told me as he waited to board the plane for the return flight to Bamako. A 97,000-square-mile wilderness of granite peaks, narrow canyons, and cul-de-sacs, the massif has long served as a sanctuary for Islamic radicals, including Mokhtar Belmokhtar, an Algerian cigarette smuggler turned kidnapper and murderer who led al-Qaeda’s takeover of northern Mali. Many jihadists sought refuge there after the French intervention in January 2013—Operation Serval—flushed them from Mali’s major towns.

There are, I was told, just two or three ways into the black mountains. “If you don’t know your way around, you cannot penetrate the massif,” said Roy Maheshe, the UN’s civil affairs officer, as we sat in the sand-filled courtyard of his dilapidated office in the cement-block buildings of the UN compound on the southern outskirts of town. As we ate a fish stew, Maheshe was somber about improving conditions in Mali’s far north, not least in the impoverished town of Kidal. Morale among the UN staff, I found, was low. “There is absolutely no government here,” Maheshe told me.

This desolate backwater at the edge of the Sahara has always been a difficult place to govern. But it wasn’t until radical Islamists found a sanctuary here that Kidal’s problems acquired global importance. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb began prowling around the edges of Kidal a decade ago, kidnapping Western aid workers and diplomats for ransom and smuggling Colombian cocaine through the Sahara to Algeria and Libya. The Tuaregs, the nomadic Berber people who are the principal inhabitants of the Sahara, make up the vast majority of the population in the Kidal region; they have historically practiced a moderate form of Islam and the Tuareg movements seeking a separate state have generally been secular rather than religious.

Three years ago, however, a local Tuareg chieftain and hostage negotiator named Iyad Ag Ghali sought out the Muslim extremists, establishing links between them and Kidal’s Tuareg population. Ghali created a violent Islamist movement known as Ansar Dine (Defenders of the Faith), recruited disaffected Tuareg youths and soldiers, and merged his organization with al-Qaeda. “He integrated the Salafists into the system, and that changed everything,” Arbacane Ag Abzayack, the mayor of Kidal since 2009, told me.

In early 2012, al-Qaeda and Ansar Dine radicals combined forces with secular Tuareg radicals, who had formed an insurgent group, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), several months earlier. This movement was the latest in a long line of organizations that have been waging periodic rebellions to form a separate state for more than fifty years. Armed with heavy weapons taken from Qaddafi’s former arsenals, they defeated the small Malian army and declared the north an independent country named Azawad. Months later, however, the jihadists turned against the secular Tuaregs, and made the region a safe haven for Islamic extremists from around the world. Islamists carried out amputations and executions, banned music, and whipped women who refused to wear the veil. They called Azawad an Islamic caliphate, vowed to carry on a war against the West, and set up terrorist training camps in the Sahara.

Advertisement

In January 2013, the jihadist militants opened a surprise offensive toward the capital in the southwest, Bamako. Days later, under orders from President François Hollande, Mali’s former colonizer, France, launched air strikes and deployed 2,150 ground forces to stop them. “The alternative was to have a jihadist state in Africa,” Brigadier General Bernard Barrera, the commander of ground forces in Operation Serval, told me. The troops drove al-Qaeda militants out of the main towns of the north, and pursued them across the desert and into the Adrar des Ifoghas mountains. The fighting in the canyons and valleys of the region was fierce, and the extremists, Barrera told me, fought “with courage and tenacity,” frequently launching suicidal charges on French commandos. But the French used tanks, attack helicopters, cluster bombs, missiles, and artillery, and had the benefit of drone surveillance provided by the US military command in Africa.

In February 2013, French or Chadian forces—it is still not clear who—killed Abdelhamid Abu Zeid, the leader of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, who was holed up in a canyon in the Adrar des Ifoghas. His body was identified through DNA samples. Barrera and his intelligence team had intercepted frequent radio emissions from Abu Zeid, exhorting his men to fight on against les chiens, or the dogs, as he called the French. Zeid’s death “weakened the morale” of the al-Qaeda troops, Barrera said, and they began to slip away from their mountain strongholds. By the spring of 2013, the French declared that virtually all of the militants had been driven out of the Adrar des Ifoghas and resistance was over. The French had suffered a total of seven deaths and a few dozen injured; they had killed “about six hundred” al-Qaeda fighters, Barrera told me, and injured hundreds more.

The French began to wind down their mission, and handed over peacekeeping to the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). Today the operation consists of a residual force of about 1,000 French troops plus 5,000 UN peacekeepers, mostly from African nations. MINUSMA eventually will have up to 11,200 troops, including reserve battalions and 1,440 police officers. “We know the French are not going to be here forever, and we are getting stronger,” General Didier Dacko, the head of the Mali army general staff, told me in Bamako.

The French mission has been widely viewed as a success—an example of a European nation going into a former colony and efficiently ridding it of an extremist threat and power. But when I visited Timbuktu in late winter, al-Qaeda launched several rockets at the airport, and clashed with French forces north of the city. Earlier, while I was in Gao, the jihadists’ former capital, 150 miles east of Timbuktu along the Niger River, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), a splinter group connected with al-Qaeda, abducted a team of five Red Cross workers on the road to Kidal, and is still holding them hostage.

The most difficult area is Kidal. When a company of French troops arrived in Kidal in February 2013, most of al-Qaeda had already fled to the nearby Adrar des Ifoghas. The French military was spread thin, and it stood by as the secular Tuareg rebels swept into the city and took control. Brigadier General Barrera told me that the French regarded their movement, the MNLA, as “neither our friends nor our enemies.” They were unwilling to risk a violent confrontation with the Tuareg rebels by trying to stop them from taking over Kidal. The French would not intervene, he said, in what was essentially a “political dispute” between Tuareg separatists who have been fighting for autonomy over their home region and a Bamako-based, non-Tuareg government whom the Tuaregs accuse of neglecting Kidal since independence.

The MNLA occupied the radio station, the old French Foreign Legion fort, the governor’s headquarters, and military camps, set up checkpoints, and moved into houses throughout the town. But the Tuareg army, tacitly supported by the French, is poorly trained and undisciplined, and al-Qaeda soon took advantage of its ineptitude. By the time a large UN peacekeeping contingent arrived in Kidal in July 2013, built a base there, and began conducting patrols in the city, dozens, if not hundreds, of heavily armed al-Qaeda and Ansar Dine militants, clearly contemptuous of the Tuareg forces, had already slipped back into the town.

Advertisement

“They blend into the population, they have a lot of money, they do what they want, and they buy the conscience of the people,” says Mayor Ag Abzayack. Now, as the French continue to withdraw their forces, the town has become a test case in the international opposition to al-Qaeda, and of the efforts to bring stability to one of the world’s most dangerous regions.

I went around Kidal with Captain Mohammed Diare, a Guinean UN peacekeeper, in an armored Toyota Land Cruiser, escorted by two Hilux pickup trucks filled with Togolese police. A career military officer who spoke fluent French, Diare had spent five years with the UN peacekeeping mission in Haiti before coming to Mali. “Down there it was just small-time bandits, looking to eat,” he said. “Here you have the jihadist presence, so you have to pay a lot of attention.” He pointed out several spots in the sand track leading out of the UN camp where al-Qaeda militants had buried IEDs—improvised explosive devices.

At the main intersection of downtown Kidal, Diare gestured to a large pile of rubble—slabs of asphalt, roof tiles, and twisted metal. It had been the Mali Solidarity Bank, destroyed by a suicide bomber at 6:45 AM last December 14, the day before a second round of parliamentary elections. Two Senegalese peacekeepers stationed in front of the bank had been killed by the powerful blast, and a dozen Malian guards inside were injured. This, Diare told me, along with other violent attacks, was probably the work of al-Qaeda, “but it could also have been the Tuareg rebels,” even though they ostensibly have good relations with the UN forces.

Last June, after negotiations supervised by the United Nations, the European Union, and regional African powers in Ouagadougou, the capital of neighboring Burkina Faso, the Malian government and the Tuareg MNLA reached a modest agreement, hailed by the French foreign minister, with some hyperbole, as “a major advance.” The MNLA agreed to permit a limited civil administration to return to Kidal, and began to surrender to the government control of important installations, including the old French fort, the radio station, the governor’s office, and the military headquarters.

Under the terms of this accord, a small number of Malian government troops, gendarmes, and police could return to the city. The MNLA also agreed to garrison its troops—many hundreds of men—in three cantonments in Kidal, and to keep their weapons stockpiled inside the garrison. “They have a huge amount of guns, from Libya,” Diare told me. The Tuareg rebels are allowed to remove them only under UN supervision. But Diare told me that they routinely violate the agreement. “What can we do to stop them?” Diare said, while passing several carloads of bearded, turbaned MNLA fighters. The UN was unwilling to risk a war, he told me, by trying to disarm the rebels.

With so many weapons in Kidal, UN forces have difficulties distinguishing one faction from another. “They can’t tell who is al-Qaeda, who is MNLA, who are the normal civilians. People come and go freely,” El Hadj Ag Gamou, a former Tuareg rebel who now serves as one of the country’s highest-ranking generals, told me. “The French don’t control it. The UN doesn’t control it. There is no control.” Didier Dacko, the chief of staff of the Mali army in Bamako, told me that you see “guys with machine guns in a car waving the flag of MNLA, but if you dig inside you will find that they are not the MNLA, but al-Qaeda.”

Dacko said that the confusion could have been avoided “if our military was in control of the situation.” But the Malian army is widely hated here because of the reprisals it carried out over decades against the Tuareg separatists and their civilian supporters during past rebellions. Just a few hundred Malian troops and gendarmes are based in Kidal and they are mostly confined to their barracks. “If the Malian troops come, there is often violence between them and the local people,” Diare told me. During our morning tour of Kidal, I watched a unit of French Special Forces extract several Malian troops who had been surrounded by angry townspeople when they ventured into the market.

Notwithstanding the initial agreement between the government and the rebels in Ouagadougou, the Tuaregs are now pushing for full autonomy over the Kidal region, their traditional homeland. The Malian government wants the UN to fully disarm the rebels, and also wants the MNLA investigated and prosecuted for crimes committed during the 2012 conflict—such as the execution-style killings of nearly one hundred captured government troops at their encampment in Aguelhok, not far from Kidal. With the talks stalled, the handful of government officials who were permitted to return to Kidal under the Ouagadougou accord are afraid to move out of their tiny quadrant of the city. The Tuareg rebels “don’t want to see a single Malian official anywhere,” said Diare.

Kidal’s schools remain closed and abandoned, because the rebels refuse to permit non-Tuareg teachers to return to work. Kidal’s hospital has had trouble functioning, because the rebels say that non-Tuareg doctors are unwelcome. We drove past the old French Foreign Legion fort—a medieval-looking monolith with crenellated walls, narrow gun slots, and a forty-foot-high central turret—that the rebels had recently given back to the government as part of the deal signed in Ouagadougou. A tattered Malian flag flew from atop the building and a handful of troops in camouflage brewed tea on a terrace. Just beyond their encampment, separated from it by a no-man’s-land, was the territory of the MNLA. The separatists roam freely through the rest of Kidal, and the Malian army rarely ventures beyond this fort. “The [Malian] government doesn’t control anything but a tiny part of the city,” Diare told me.

Ghislaine Dupont, fifty-one, and Claude Verlon, fifty-eight, veteran journalists for Radio France Internationale, the state-subsidized broadcaster, discovered this last November, with tragic results. They arrived in Kidal, as I did, on a United Nations flight from Bamako. Basing themselves at city hall in the center of town, they hired a car and driver, and circulated openly for several days. “I warned them that it was dangerous to be on their own, without an armed escort,” said Vincent Malle, the UN security chief, who advised them to stay inside the UN compound. “but they had been here before, in July [to cover the presidential election], and nothing had happened to them. They felt safe.”

On the afternoon of November 2, Dupont and Verlon interviewed a Tuareg separatist leader at his house, located on a wide, sandy road lined with mud-walled compounds, a mile from the UN compound. As they left, turbaned gunmen intercepted them and forced them into a car. Their driver “heard the two reporters protest and resist. It was the last time they were seen alive,” RFI reported. The gunmen, who spoke Tamasheq—the language of the Tuaregs—headed north toward the Adrar des Ifoghas, with UN troops in pursuit. When their car broke down about eight miles north of the city, the abductors decided to kill Dupont and Verlon. French troops recovered their bullet-riddled corpses by the side of the road. The gunmen escaped into the desert.

Al-Qaeda claimed that it had carried out the killings in retaliation for the “daily crimes” committed by French and Malian forces in northern Mali. “The organization considers that this is the least of the price which President François Hollande and his people will pay for their new crusade,” read a statement issued on a jihadist website days after the murders. According to Malian intelligence, a low-ranking al-Qaeda member living in Kidal had concocted the kidnap plot, hoping to use the ransom to pay back money that he had been accused of stealing from his superiors. “That’s the idea that’s circulating in town now: All you have to do is kidnap a Westerner, and you can get millions,” an official in Kidal told The New York Times in November. The kidnappers reportedly belonged to an al-Qaeda faction led by Abdelkrim al-Targui, a cousin of Iyad Ag Ghali, and one of a handful of Malian Tuaregs who have become important players in al-Qaeda in the Islamic Magreb, which is dominated by Arabic-speaking, Algerian extremists.

Mayor Arbakan Ag Abzayack of Kidal, an imposing man wearing a black turban, sunglasses, and a peacock-blue traditional gown known as a bubu, told me that he had been the host of the French journalists during their first visit to Kidal in July 2013, and became friends with them. They had slept in his office on their second, fatal visit in November, since he had been in Bamako at the time. “The Islamic extremists are like cancer,” Abzayack said, as we stood, surrounded by UN police, in front of his mud-walled compound on a barren, gray-sand slope on Kidal’s northern outskirts. “You have to isolate them in a corner, but it’s difficult to do,” said the mayor. “It’s not going to be easy to break this system.”

Most observers I spoke to say that al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb is too weak to reconstitute itself. “They no longer have the ability to mount operations with hundreds of fighters as they did in Gao, and the Adrar des Ifoghas,” Barrera told me. “They move around in small groups, and they’re capable of mounting only limited attacks. Mostly they hide themselves, and we destroy them from time to time.” The French are continuing to hunt down the remaining Islamist leaders. In March, French commandos killed Oumar Ould Hamaha, an influential jihadist known as “Red Beard,” who had often vowed in TV interviews to kill Westerners, and who had a $5 million US government bounty on his head.

The extremists continue to hold Western hostages. In late April, MUJAO, an al-Qaeda-affiliated movement, announced that Gilberto Rodrigues Leal, sixty-two, a Frenchman the group seized in November 2012 in a café in western Mali, “is dead because France is our enemy.” French President François Hollande’s office said that Rodrigues Leal had probably died several weeks ago as a result of abusive treatment by his captors. Other sources have said that Rodrigues Leal died after falling ill and being denied medical treatment. France’s last surviving hostage in Mali is Serge Lazarevic, fifty, an independent businessman kidnapped in November 2011.

But the desert is vast, with innumerable hiding places, and the extremists have long experience in holding on to their weapons, hiding their fuel and food, and surviving on the run. Notwithstanding his assurance about the recapture of territory, Barrera says that without “constant surveillance” and military pressure on al-Qaeda, the threat to the region, and ultimately to parts of Europe and beyond, will not dissipate. As the French continue to scale down operations and turn over responsibility for the country’s security to an all-African force, there is a growing sense that they are leaving with their mission and job half done, that an ominous future involving Tuareg rebellion and proliferating jihadists lies ahead.

This Issue

May 22, 2014

How Memory Speaks

The Phony War?

Elizabeth Warren’s Moment