In late April, traveling in eastern Ukraine, I was in the midst of its phony war. Threats were flying, ultimatums were delivered, and jets screamed low over the countryside. Trees were felled to block back roads, tires were piled up to build barricades, and men from backwater towns strutted with their guns, their lives suddenly seeming to have purpose. In eastern Ukraine, where neatly kept memorials commemorate the fallen of the great battles fought there by the Red Army during World War II, all the omens seemed to tell of war coming once again. But even at the eleventh hour it is not inevitable.

This has been a time when normal life continues while men arm themselves and begin to prepare for combat. It is that strange pre-war moment when the possible future overlaps with the present. Rebels make Molotov cocktails a stone’s throw from roadside shops selling garden gnomes. A halted Ukrainian army convoy is surrounded by locals who mill around chatting to the soldiers. The line of armored vehicles is split by a train coming from a Russian holiday resort; it goes through Ukraine because that is the way the Soviet-era track goes. It blows its horn to get crowds out of the way as it passes on its way to Moscow. People wave to the passengers who peer out, wondering what is going on.

As men in beaten-up cars race up country roads past towering grain silos, as groups gather to demand referendums, as people tell me that they don’t believe that war is coming and that Russians and Ukrainians are brothers, I remember the same brave talk, the same euphoria, and the same delusions before the Yugoslavs tipped their country into catastrophe in the 1990s. Ukraine is not like that Yugoslavia, although the atmosphere in the east is a horribly similar combination of resentment and disbelief.

1.

What is extraordinary about the Ukrainian disaster is how fast things have moved. Last October, when I came to talk to people about the country signing a trade deal with the European Union, I was told again and again that Ukraine had a date with destiny. It would look west, not east to Russia. Almost everyone I met thought the deal would happen. President Viktor Yanukovych, the head of the Party of Regions, whose support came mostly from the east, had, when he was elected, been regarded as pro-Russian. Yes, it will be tough, officials said, but the future was with Europe and he would sign.

At the last minute Yanukovych balked. Vladimir Putin decided to stop the deal from being signed. If Ukraine agreed to it, then it could not join his planned Eurasian Union, with Belarus and Kazakhstan, which would be dominated by Russia. Giving in to Putin’s demands, which were accompanied by his promise of lowered gas prices, Yanukovych said he would not sign, at least for now. Immediately pro-European Ukrainians began demonstrating in Kiev and other towns and thousands kept up the pressure for months. More than a hundred protesters were killed. Some seventeen police and Berkut, or riot police, many from the predominantly Russian-speaking south and east, were killed or injured by a small group of hard-core and often far-right anti-Yanukovych protesters, who also seized several buildings in the center of Kiev. Because the epicenter of all this was the Maidan, the central square of the Ukrainian capital, it became known as the “Maidan revolution.”

After Yanukovych fled on February 21, soon to resurface in Russia, parliament replaced him by electing an interim president and government, whose members and supporters come mostly from the center and west of the country. A presidential election was set for May 25. The incoming government thought that its main task would be dealing with the disastrous state of the economy. No one foresaw that Crimea, a predominantly Russian-speaking region that had historically been part of Russia, would—thanks largely to Putin’s interventions, both political and with, as he has subsequently admitted, covert military support—become the center of the action.

In short order, hitherto marginal political forces whipped up latent resentment. One of the first acts of parliament, a vote to downgrade the legal status of the Russian language, was immediately vetoed by the new president, Oleksandr Turchynov. But the vote provided a pretext for Putin and pro-Russian activists in Crimea to take action. With the help of Russia, a referendum was quickly improvised on the status of Crimea, and Russia and its allies claimed that 97 percent of the votes counted were for its incorporation into Russia.

The peninsula was promptly annexed. Those who were against annexation said the vote was illegal and didn’t take part. The government in Kiev ordered its weak forces not to fight, especially as they would have been ranged against Russian troops based in Crimea with its Black Sea fleet. Resistance to the Russian takeover could also have prompted a full-scale invasion. But Oleh Shamshur, a former ambassador to the US, told me, “If a hooligan meets no resistance he is emboldened. We should have fought and resisted.”

Advertisement

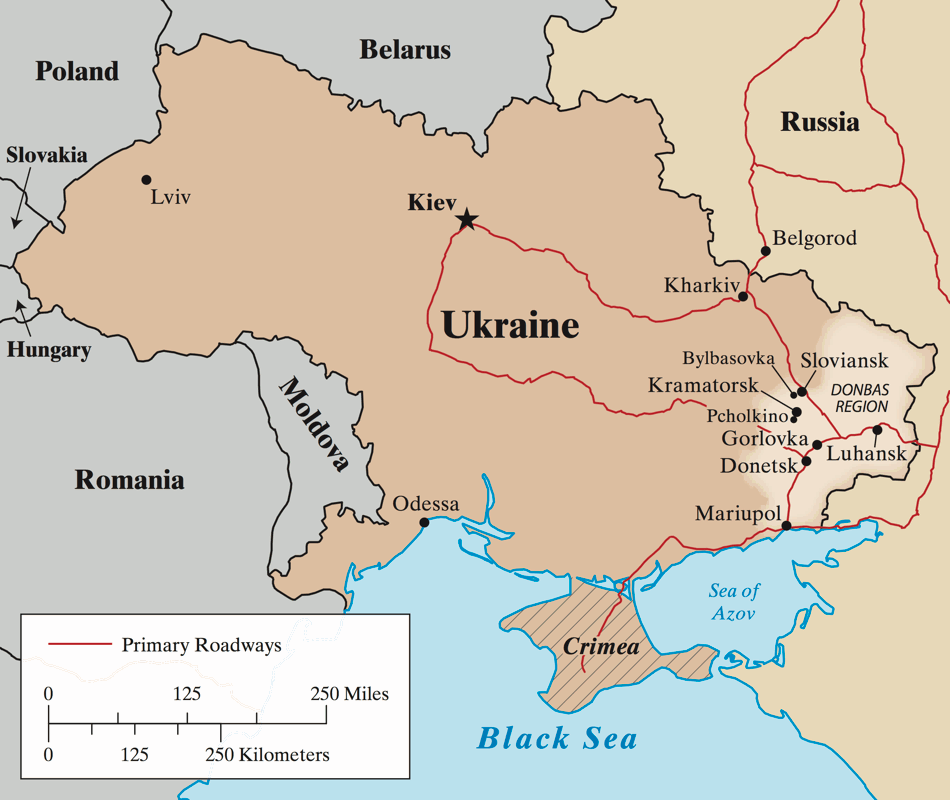

Then came the protests in the east. After the fall of Yanukovych, demonstrations against the new government began in Donetsk, the capital of mostly Russian-speaking Donbas, an industrial and mining region. Donetsk, a city of almost a million people, is only fifty miles from the Russian border, and the government in Kiev said that Russian agents were being sent across it to stir up trouble and organize the events that subsequently unfolded. On April 6 the local administration building was seized by armed men who declared the People’s Republic of Donetsk and said they would hold a referendum on the future status of the region.

A couple of thousand people demonstrated their support for the takeover outside the building. Some demanded a federal Ukraine and some wanted Donbas to become part of Russia. Barricades were built and people told me that if it was okay for pro-Europeans to seize buildings around the Maidan, then it was okay for them to do the same to get their point across too. But who exactly were the people inside the Donetsk building and in another seized building in the town of Luhansk? That remained unclear. A skeptical reporter summed them up as the “Republic of Random Dudes.” The authorities in Kiev said they were working for Russia. On the barricades they placed both Russian flags and a black, blue, and red tricolor, the banner of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic, which declared independence from Ukraine in February 1918 and lasted six weeks.

If those behind the seizure of the two buildings thought they would inspire large-scale demonstrations that would go on as long as those on the Maidan, they were wrong. On April 11 there were no more than a couple of hundred people milling around. Yulia Yefanova, aged twenty-four, who was posing for pictures in front of a mock Russian frontier post, told me she wanted Donbas to unite with Russia because links between them were very close and much of her family was in Russia. As people crowded around us, they began shouting their opinions. “It is impossible to be friends with Europe and with Russia,” said one man who did not want to give his name. “They are like cat and dog.” Another said: “If Russia was here, it would put everything in order. It would fight corruption.”

Many told me that they believed that the hardworking people of Donbas subsidized lazy people in the center and west of Ukraine—a common belief and stereotype here. Repeating what they hear from Russian media, they claimed the government in Kiev was a “fascist junta.” One woman said: “Only Russia can save us from a power that is not democratic,” by which she meant the new government in Kiev. There didn’t seem to be many people with such virulent views. As the numbers outside the headquarters of the Republic of Random Dudes dwindled, the general impression of many in the city was that things were fizzling out.

2.

Early in the morning of April 12 everything changed in Donetsk. A small but forceful group of protesters gathered outside the regional police headquarters. Who organized them was not clear. Within a few hours a group of beefy men took charge. They were wearing the uniform of the Berkut police, whose units had been disbanded by the new Kiev government for attacking the anti-Yanukovych protesters on the Maidan. But they remain popular with many in the east. Disconsolate-looking local policemen stood around while Berkut and other armed men, whose affiliations were not clear, moved into the occupied buildings with shopping bags of food and water bottles, as though preparing for a siege.

Over the next few days the same pattern of events began to repeat itself elsewhere in eastern Ukraine with only a few variations. Buildings belonging to the security services were taken over in a string of small industrial and mining towns including Sloviansk, Kramatorsk, and Gorlovka. From Kramatorsk a video surfaced showing a well-trained military unit shooting into the building before seizing it. The local police surrendered, and the military unit left armed local protesters in charge.

In Gorlovka thuggish men armed with clubs stormed the police building. A policewoman dropped a piece of paper out of the window, presumably a surrender of some sort. But not everyone surrendered. The police chief and his deputy resisted but within a couple of hours the struggle was over. The deputy was beaten and made to kneel before being sent off in an ambulance.

Advertisement

In Sloviansk, barricades were put up by antigovernment forces both around the town and inside it. Old ladies holding icons and saying that all they wanted was peace stood in front of the barricades at the entrance to the town. Behind them men filled Molotov cocktails, and behind them a couple of armed men in uniforms gave instructions to others. Inside the town, in front of the barricades by the seized police station, an old man stood on the pavement with a sheet of paper pinned to his coat. It read: “All to the USSR.” Many men wore ski masks or surgical masks. They covered their faces, one told me, because if their rebellion fails, they could face long jail sentences.

A small crowd broke into chants of “Donbas rise up!” and “Russians don’t surrender!” As in Donestsk, I heard people express different views. All of them said they hated the new government in Kiev but what they wanted was less clear. A man called Viktor told me that he wanted “respect” from it. Many told me that, although they did not like Yanukovych, they had voted for him as one of their own, an easterner whom they had hoped would look after their interests. A woman called Olga told me, “He robbed from us even more than elsewhere.” Now, however, some felt that their interests were being taken into account even less.

A concern that I kept hearing was that if Ukraine were drawn toward Europe, industry in the east, which mostly trades with Russia, would suffer. When local factories found it hard to compete with counterparts in the EU, they would shut down and people would lose their jobs.

Over the next few days it became clear that, with the fall of Yanukovych, the power of the Ukrainian state in the east had simply evaporated. It seemed inexplicable that the government in Kiev was not reacting as large parts of eastern Ukraine fell to the rebels. Looking at the map, one could see that all the towns where there had been serious trouble lay at strategic rail junctions or on the main road from Belgorod in Russia, where a large part of a potential invasion force of some 35,000 troops is stationed. The road runs south to Kharkiv, where there have been clashes between pro- and anti-government crowds, all the way down to Mariupol on the Black Sea. In the towns on this road, one building after another belonging to the security services was invaded. Police forces either surrendered or defected or became neutral. Rebels took over their arms.

On April 15 the Ukrainian government seemed prepared to fight. A column of armored personnel carriers and buses with interior ministry troops was lined up along the road north of Sloviansk. A few hours later the local and Russian media were reporting armed conflict and deaths. The Russian media said that “genocide” was being committed in Ukraine. Putin declared that the country was on the brink of civil war. The Ukrainian government announced that a military airbase near Kramatorsk was being retaken from rebels.

As it turned out, these statements, amplified to the power of a million by Twitter, were all exaggerated. Ukrainian troops had flown into the decrepit and apparently empty base by helicopter. There had been some ugly jostling with locals, resulting, said an old lady, in three of them being “grazed.” A stall was set up near the base to hand out sandwiches and tea to people who were blockading the Ukrainian forces inside.

The next day two columns of the government’s armored vehicles were finally sent into action. By nightfall, it was clear that, thus far at least, the Ukrainian advance was in tatters. In Pcholkino, near Kramatorsk, one column had been held up by locals and armed militiamen. The soldiers could have opened fire on the crowds but didn’t. They sweltered in the sun on the tops of their vehicles. Locals chatted with them and brought them food. A tall and forceful local priest, called Igor, moved between vehicles lecturing the soldiers: “Why didn’t you refuse to take part,” he asked them, “and say ‘I will not shoot’?” A few hours later the soldiers were allowed to leave with their vehicles.

In Sloviansk, the soldiers of the other convoy of armored vehicles were subjected to much worse humiliation. After being stopped on the road outside the town by locals and militia, they were brought into the center. There some forty of them spent most of the day under armed guard before being put on buses and sent home. “We have not defected,” one told me. A small crowd looked at them, including two flirty girls who giggled that they were looking for husbands.

As the soldiers left, the crowd applauded and shouted: “Good guys!” “Thank you!” and “Well done!” The soldiers looked as miserable as the authorities in Kiev must have felt. Neatly dressed rebel militiamen now lolled on their captured armored vehicles in the park close to a playground. By early afternoon people were lining up to have their pictures taken with them. The next day President Turchynov said that the soldiers who had surrendered were traitors and would be court-martialed. Having sent them into a situation in which, to get out, they would have had to shoot civilians and then risk being killed themselves, this sounded like the commander in chief was blaming his soldiers for hapless decisions made by their officers.

3.

Is Putin behind all this, and if so what is his goal? No one seemed to know for sure. Yuriy Temirov, an analyst at Donetsk’s university, says that he believes some local oligarchs have been financing the rebel organization, though others are clearly supporting Ukraine. Russia certainly has its interests in Ukraine and there is strong, although disputed, evidence suggesting that Russian military and intelligence agents were involved in the takeovers; but Putin’s interests are not the same as those of the oligarchs financing the rebels. “The local bosses don’t want any authority here, either state or Russia,” Temirov told me. But Putin, he believes, has made “efficient” use of the local bosses, who have unwittingly “done the dirty work of the Kremlin.” One of them is widely believed to be Oleksandr Yanukovych, the son of the former president, who had been a dentist and then became fabulously wealthy when his father was in power.

Whoever is backing them, the rebels clearly have some measure of popular support, but how much is hard to estimate. Temirov says that two opinion polls conducted since demonstrations started in the east show a majority in Donbas in favor of staying a part of Ukraine. One survey, conducted by a research organization he works with, found that 66 percent wanted to remain in Ukraine and only 18.6 percent wanted to join Russia. What was clear was that ordinary life was continuing around the occupied buildings.

On April 17 some two thousand people gathered for a pro-Ukrainian rally in Donetsk. Many told me that this was a good turnout because others had been frightened to come, fearing they would be attacked by anti-government supporters, as happened at a rally in March. Oleh Lyasko, a presidential candidate and the leader of a small party, told the crowd that the country faced “the choice of shame or war and I am for war.” Seeing those at the rally, I sensed that there is a class element in the conflict. The more middle-class you are in Donetsk the more you are likely to support Ukrainian unity. The more working-class you are, the more resentment you are likely to feel at the loss of status, security, and standard of living in the post-Soviet state.

Still, whatever the level of support for unity, it is clear that Russia cannot replicate the outcome in Crimea in the east. According to Professor Grigory Perepelytsa, the director of the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Kiev, if Russia invades, Ukrainian forces are too weak to fight; but Russia might well be faced with spontaneous partisan resistance. In his view, Russia might invade anyway. Putin, he and many others believe, has set himself the task of reversing what he regards as the geopolitical disaster of the end of the USSR. When I asked if that meant that Russian troops might even come as far as Kiev, he said, “Yes, that is the final goal.”

Clearly there are other possibilities. One is that Putin is manipulating eastern anger because he wants to destabilize Ukraine in order to dominate, divide, and rule. If martial law is declared in all or part of the country, then it will be difficult to hold an election on May 25. Putin will then continue to argue that the authorities in Kiev are illegitimate. He will also count on the covert military agents, the so-called “little green men,” he has almost certainly sent to direct the locals. They have no insignia and thus might, as the local joke goes, have just landed from Mars. On April 22, Vice President Biden said, “We call on Russia to stop supporting men hiding behind masks in unmarked uniforms, sowing unrest in eastern Ukraine.”

Putin may not be planning a full-scale occupation but instead trying to force the federalization of Ukraine. If that takes place, he won’t have the huge expense of absorbing the region. He will not risk a major war or really crippling sanctions from the West. Still, Russia would call the shots in the east of the country. The local oligarchs, who unlike in Russia have real political power, could be brought under control—and one day in the future if it were convenient, it might be possible to break off a now growing People’s Republic of Donetsk from Ukraine. If such a “republic” emerges, the question will be how far it can extend its power.

4.

Before leaving for the east I visited the remaining tented encampments around the Maidan, where I was told that an estimated one thousand people have said they will stay, at least until the presidential election in May. Many of the men and women had come from the provinces: the days on the Maidan had given them a sense of purpose they had never experienced. Now it is hard for them to return to their humdrum lives back home.

Between the square and the Rada, the Ukrainian parliament, all sorts of militias in different uniforms marched up and down, to no clear purpose. Outside the Rada I asked a militia leader what he and his men were doing and whether they might not serve Ukraine better in the east. He said, “If we left this spot, provocations would start here.” He said that provocateurs could be agents of the FSB, Russia’s secret service, and other supporters of Russia.

While the threat of losing complete control of the east seemed a real one, all sorts of people and groups demonstrated outside the Rada. Some were demanding that judges under the Yanukovych regime be disqualified; some were protesting about legislation concerning duties on imported cars. Given the gravity of the situation in the east I was surprised by how far away it seemed from the concerns of ordinary people and even politicians in Kiev.

Many Ukrainians I spoke to were alarmed and disappointed. They had braved the cold and violence for a major change in the country, but now the leading candidates for president were Yulia Tymoshenko, an oligarch and former prime minister who had been jailed by Yanukovych, and Petro Poroshenko, a billionaire who had backed the Maidan protests but before that had been a minister under Yanukovych. According to the polls, he was in the lead.

Middle-class Natalyia, aged forty-eight, who did not want me to use her surname and who works for an American company, said she had liked what she had seen at the beginning on the Maidan, but later felt that “political games were being played” there by Russia, the EU, and the US. She was “anxious, but not fearful” of war. What concerned her and many of her friends even more was the cost of living.

Her husband, an engineer, works for a company whose orders have plummeted because of the crisis, and he’s now worried about losing his job. Meanwhile, like many in the region, they have a mortgage that must be paid in a foreign currency. Few understood the implications of such arrangements when they borrowed. Before the financial crisis of 2008, she told me, $1 equaled 5.5 Ukrainian hryvnia. Before the Maidan protest started it was 8 hryvnia. Today it is over 11 hryvnia. For ordinary people unbearable pressures are piling up on all sides.

Everywhere across the Maidan were red and black flags. According to Andreas Umland, a specialist on the far right in the post-Soviet countries, many in western and central Ukraine see them as flags of freedom. This was the flag of the forces of Stepan Bandera, who led western Ukrainian forces during World War II, at times collaborating with Hitler, and whose men were implicated in pogroms of Jews and massacres of Poles. But Bandera’s followers also fought the returning Soviets well into the 1950s. The red and black colors stand for blood and soil, Umland told me, though most people don’t know that today.

Charges that the new government is anti-Semitic and fascist have been circulated by Moscow but have been repeated in the West. At their root is the presence in the government of members of Svoboda, a party based in western Ukraine that had neo-Nazi roots. “People in government are not fascists,” Umland told me categorically, “but some people in Svoboda could be classified as fascists.” He drew parallels with parties such as France’s National Front.

In Donetsk, I was invited to attend the Jewish community Seder, on the eve of Passover. I was surprised by how relaxed people seemed to be, in view of the dire state of the country and fears being raised about anti-Semites in government. The stories about anti-Semitism were “pumped up” by Moscow, people told me. As for fears of war and what might happen in the east, local Jews were worried, but not more than anyone else.

The next day three men in masks distributed a leaflet as people came out of synagogue. It was purportedly signed by Denis Pushilin, the head of the Donetsk Republic. It ordered Jews, whom it accused of siding with the “Bandererite junta in Kiev,” to register or leave the city. The news made headlines around the world and provoked a denunciation from John Kerry. Pushilin said the letter was a fake. One of the more credible explanations I heard discussed in the Jewish community was that it was possibly concocted by the local office of the Ukrainian secret service in what turned out to be a spectacularly successful black propaganda coup to smear the Donetsk Republic.

Kerry spoke on April 17, the same day that he, Sergei Lavrov, his Russian counterpart, the Ukrainian foreign minister, and the EU’s foreign policy chief agreed in Geneva that all illegally held buildings and public spaces should be evacuated and that discussions should begin on a “broad national dialogue.” The next day Pushilin rejected this. He and his men would leave the administration building in Donetsk only when the new government in Kiev dissolved because, he said, members of that government had seized power in a putsch, and hence they were occupying government buildings illegally. In the early hours of Easter Sunday, a shootout at a rebel checkpoint surrounded by fields at Bylbasovka, near Sloviansk, led to a number of dead, though how many and exactly what had happened was unclear. The phony war teetered on the edge of turning real.

—April 24, 2014

This Issue

May 22, 2014

How Memory Speaks

Elizabeth Warren’s Moment